Charles Booth (social reformer)

Charles James Booth (30 March 1840 – 23 November 1916) was a British shipowner, social researcher and reformer, best known for his innovative philanthropic studies on working-class life in London towards the end of the 19th century.

Charles Booth | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 30 March 1840 Liverpool, Lancashire, England |

| Died | 23 November 1916 (aged 76) Thringstone, Leicestershire, England |

| Resting place | St Andrew's, Thringstone |

| Occupation | Shipowner and social reformer |

Notable work | Life and Labour of the People in London |

| Spouse(s) | Mary née Macaulay |

| Awards | Guy Medal |

Booth's work, along with that of Benjamin Seebohm Rowntree, influenced government policy regarding poverty in the early 20th century and helped initiate Old Age pensions and free school meals for the poorest children.

Biography

Charles Booth was born in Liverpool, Lancashire on 30 March 1840 to Charles Booth and Emily Fletcher. His father was a wealthy shipowner and corn merchant as well as being a prominent Unitarian.[1] He attended the Royal Institution School in Liverpool before being apprenticed in the family business at the age of sixteen.[2] He joined his brother, Alfred Booth, in the leather trade in 1862 and they subsequently established a successful shipping firm together, and Charles remained actively involved with it until his retirement in 1912.[3]

Booth became alienated from the dominant, nonconformist business class of Liverpool into which he had been born, and, following his marriage in 1871 to Mary Macaulay, the couple settled in London.[4] The niece of the historian Thomas Babington Macaulay,[2] she was a cousin of the Fabian socialist and author, Beatrice Webb. They had 7 children, 3 sons and 4 daughters

His eldest daughter Antonia[5] married the Hon Sir Malcolm Macnaghten, and others married into the Ritchie and Gore Browne families.[6]

Career

Booth's father died in 1860, leaving him in control of the family company. He entered the skins and leather business with his elder brother Alfred, and they set up Alfred Booth and Company with offices in Liverpool and New York City using a £20,000 inheritance.[2] In 1865 Booth ran for Parliament as the Liberal candidate for Toxteth, Liverpool, but was unsuccessful.[7]

After learning the shipping trades, Booth was able to persuade Alfred and his sister Emily to invest in steamships and established a service to Pará, Maranhão and Ceará in Brazil. Booth himself went on the first voyage to Brazil on 14 February 1866. He was also involved in the building of a harbour at Manaus which overcame seasonal fluctuations in water levels. Booth described this as his "monument" (to shipping) when he visited Manaus for the last time in 1912.[8]

Social Research

Influenced earlier by positivism, he embarked in 1886 on the major survey of London life and labour for which he became famous and is commonly regarded as initiating the systematic study of poverty in Britain.[4] Booth was critical of the existing statistical data on poverty. By analysing census returns he argued that they were unsatisfactory and later sat on a committee in 1891 which suggested improvements which could be made to them.[2] Due to the scale of the survey, results were published serially but it took over fifteen years before the full seventeen volume edition was published. His work on the study and his concern with the problems of poverty led to an involvement in campaigning for old-age pensions and promoting the decasualization of labour.[4]

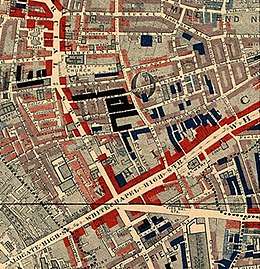

Booth publicly criticised the claims of the leader of the Social Democratic Federation H. M. Hyndman – leader of Britain's first socialist party. In the Pall Mall Gazette of 1885, Hyndman stated that 25% of Londoners lived in abject poverty.[9] The survey of life and labor began with a pilot study in Tower Hamlets. Booth then hired numerous researchers to assist with the full study of the whole of London, which investigated the three main topics of poverty, occupations, and religion.[4] Among his researchers were his cousin Beatrice Potter (Beatrice Webb) and the chapter on women's work was conducted by the budding economist Clara Collet. This research, which looked at incidences of pauperism in the East End of London, showed that 35% were living in abject poverty – even higher than the original figure. This work was published under the title Life and Labour of the People in 1889. A second volume, entitled Labour and Life of the People, covering the rest of London, appeared in 1891.[10] Booth also popularised the idea of a 'poverty line', a concept conceived by the London School Board.[11] Booth set this line at 10 to 20 shillings a week, which he considered to be the minimum amount necessary for a family of 4 or 5 people to subsist.[12]

After the first two volumes were published Booth expanded his research. This investigation was carried out by Booth himself with his team of researchers. Nonetheless, Booth continued to oversee his successful shipping business which funded his philanthropic work. The fruit of this research was a second expanded edition of his original work, published as Life and Labour of the People in London in nine volumes between 1892 and 1897. A third edition (now expanded to seventeen volumes) appeared 1902–3.[13]

Booth used his work to argue for the introduction of Old Age Pensions which he described as "limited socialism". Booth argued that such reforms would help prevent a socialist revolution from occurring in Britain. Booth was far from tempted by the ideals of socialism, but had sympathy with the working classes and, as part of his investigations, he took lodgings with working-class families and recorded his thoughts and findings in his diaries.[14]

The London School of Economics keeps his work on an online searchable database.[15]

Methodology

For the purposes of poverty measurement, Booth divided the working population into eight classes, from the poorest to the most well-off and he labeled these A—H. These categories summarized economic circumstances but also had a moral dimension, with ‘A’ representing the ‘feckless, deviant or criminal’ groups.[16]

According to Professor Paul Spicker,[17] "it is important to note that Charles Booth's studies of poverty are widely misrepresented in the literature of social policy. His work is commonly bracketed with Rowntree's, but his methods were quite different. His definition of poverty was explicitly relative; he based the description of poverty on class, rather than income. He did not attempt to define need, or to identify subsistence levels of income on the basis of minimum needs; his “poverty line” was used as an indicator of poverty, not a definition. His approach was to identify the sorts of conditions in which people were poor, and to describe these conditions in a variety of ways. To this end, he used a wide range of qualitative and quantitative methods in an attempt to add depth and weight to his descriptions of poverty."[18]

Criticisms

The survey has been negatively criticized for its methodology. Booth used school board visitors — those who undertook to ensure the attendance of children at school - to collect information on the circumstances of families. However, his extrapolation from these findings to families without school-age children was speculative. Moreover, his ‘definitions’ of the poverty levels of household ‘classes’ were general descriptive categories that did not equate to specific criteria. Although the seventeen volumes were dense with often fascinating detail, it was primarily descriptive rather than analytical.[16]

Influence of his work

Life and Labour of the People in London can be seen as one of the founding texts of British sociology, drawing on both quantitative (statistical) methods and qualitative methods (particularly ethnography). Because of this, it was an influence on Chicago School of Sociology (notably the work of Robert E. Park) and later the discipline of community studies associated with the Institute of Community Studies in East London.[19]

Booth's poverty maps revealed that there is a spatial component to poverty as well as an environmental context of poverty. Before his maps, environmental explanations of poverty mainly interested health professionals; Booth brought environmental issues into empirical sociological investigation.[16][20]

In addition to Booth's influence on the field of sociology, he influenced other academics as well. Llewellyn Smith's repeat London survey was inspired by Booth.

Booth's work served as an impetus for Seebohm Rowntree's; he also influenced Beatrice Webb and Helen Bosanquet.[21]

The importance of Booth's work in social statistics was recognised by the Royal Statistical Society, when in 1892 he was elected President and was awarded its first Guy Medal in Gold. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1899.[22]

Antisemitism

Booth's 1902 study included antisemitic references to the impact of Jewish immigration, comparing it to the "slow rising of a flood" and that "no Gentile could live in the same house with these poor foreign Jews, and even as neighbours they are unpleasant; and, since people of this race, though sometimes quarrelsome amongst themselves, are extremely gregarious and sociable, each small street or group of houses invaded tends to become entirely Jewish".[23] Although Jews were statistically only a small part of the cigar trade in the United Kingdom, Booth saw the trade as "almost entirely in the hands of the Jewish community" in the East End.[24]

Politics

Booth had some involvement in politics, although he canvassed unsuccessfully as the Liberal parliamentary candidate in the General Election of 1865. Following the Conservative Party victory in municipal elections in 1866, his interest in active politics waned. This result changed Booth's attitudes, and he foresaw that he could influence people more by educating the electorate, rather than by being a representative in Parliament.[2]

He declined subsequent offers from PM William Ewart Gladstone of elevation to the peerage with a seat in the House of Lords. Booth engaged in Joseph Chamberlain's Birmingham Education League, a survey which looked into levels of work and education in Liverpool. The survey found that 25,000 children in Liverpool were neither in school or work.[25]

While Booth's attitudes towards poverty might make him seem fairly left-wing, Booth actually became more conservative in his views in later life. Some of his investigators such as Beatrice Webb became Socialists as a result of this research, however Booth was critical of the way in which the Liberal Government appeared to support Trade Unions after they won the 1906 General Election.[26]

Later life

Booth purchased William Holman Hunt's painting The Light of The World, which he donated to St Paul's Cathedral in 1908.[27]

Early in 1912 Booth stood down as chairman of Alfred Booth and Company in favour of his nephew Alfred Allen Booth, but in 1915 returned willingly to work under wartime exigencies despite growing evidence of heart disease.

In later life, Booth retired to Grace Dieu Manor near Thringstone, Leicestershire. He died on 23 November 1916 and was buried in Saint Andrew's churchyard. A memorial dedicated to him stands on Thringstone village green, and a blue plaque has been erected on his house in South Kensington: 6 Grenville Place.[28]

Selected works

- Life and Labour of the People, 1st ed., Vol. I. (1889).

- Labour and Life of the People, 1st ed., Vol II. (1891).

- Life and Labour of the People in London, 2nd ed., (1892–97); 9 vols.

- Life and Labour of the People in London, 3rd ed., (1902–03); 17 vols.

See also

Notes and references

- "Who was Charles Booth? - Charles Booth's London". Booth.lse.ac.uk. Retrieved 5 January 2018.

- Who was Charles Booth? Booth.lse.ac.uk. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- Scott, John (8 December 2006). Fifty Key Sociologists : The Formative Theorists (1st ed.). Routledge. pp. 14–15. ISBN 978-0415352604.

- Scott, John (8 December 2006). Fifty Key Sociologists : The Formative Theorists (1st ed.). Routledge. p. 15. ISBN 978-0415352604.

- www.cracroftspeerage.co.uk

- www.thepeerage.com

- Caves, R. W. (2004). Encyclopedia of the City. Routledge. p. 47.

- Norman-Butler, Belinda (1972). Victorian Aspirations. London: Allen & Unwin. p. 177. ISBN 0-04-923059-X.

- Fried, Albert & Richard Ellman. (Eds.) (1969) Charles Booth's London. London: Hutchinson. p. xxviii.

- The reversal of the words in the title of the second volume was due to the original title "Life and Labour" being claimed by Samuel Smiles who wrote a similarly titled book in 1887.

- Gillie, Alan (1996). "The Origin of the Poverty Line". The Economic History Review. 49 (4): 715–730 [p. 726]. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0289.1996.tb00589.x.

- Boyle, David. The Tyranny of Numbers. p. 116.

- Fried, Albert & Richard Ellman. (Eds.) (1969) Charles Booth's London. London: Hutchinson; p. 341.

- www.nationalarchives.gov.uk

- Booth Poverty Map & Modern map (Charles Booth's London) LSE. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- Scott, John (8 December 2006). Fifty Key Sociologists : The Formative Theorists (1st ed.). Routledge. p. 16. ISBN 978-0415352604.

- www.unesco.org

- Spicker, Paul (May 1990). "Charles Booth: the examination of poverty". Social Policy & Administration. 24 (1): 21–38. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9515.1990.tb00322.x. hdl:10059/881.

- www.ukdataservice.ac.uk

- Bales, Kevin (1994). "Early Innovations in Social Research" (PDF). Retrieved 9 October 2019. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Scott, John (8 December 2006). Fifty Key Sociologists : The Formative Theorists (1st ed.). Routledge. pp. 16–17. ISBN 978-0415352604.

- www.royalsociety.org

- Feldman, David. (1994) Englishmen and Jews. p. 166.

- Alderman, Geoffrey. (1992) Modern British Jewry. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 8.

- www.liberalhistory.org.uk

- www.warwick.ac.uk

- "The Light of the World - St Paul's Cathedral". Stpauls.co.uk. Retrieved 5 January 2018.

- "Charles Booth blue plaque". openplaques.org. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Charles Booth. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Booth, Charles. |

- Charles Booth's London: Poverty maps and police notebooks, LSE

- Works by or about Charles Booth at Internet Archive

- Charles Booth Papers at Senate House Library, University of London

- Spartacus description of Booth's life

- Charles Booth and poverty mapping in late nineteenth century London, Middlesex University Business School