Cerium

Cerium is a chemical element with the symbol Ce and atomic number 58. Cerium is a soft, ductile and silvery-white metal that tarnishes when exposed to air, and it is soft enough to be cut with a knife. Cerium is the second element in the lanthanide series, and while it often shows the +3 oxidation state characteristic of the series, it also exceptionally has a stable +4 state that does not oxidize water. It is also considered one of the rare-earth elements. Cerium has no biological role in humans and is not very toxic.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cerium | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˈsɪəriəm/ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Appearance | silvery white | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Standard atomic weight Ar, std(Ce) | 140.116(1)[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cerium in the periodic table | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic number (Z) | 58 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Group | group n/a | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Period | period 6 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Block | f-block | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Element category | Lanthanide | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | [Xe] 4f1 5d1 6s2[2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrons per shell | 2, 8, 18, 19, 9, 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase at STP | solid | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | 1068 K (795 °C, 1463 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | 3716 K (3443 °C, 6229 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density (near r.t.) | 6.770 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| when liquid (at m.p.) | 6.55 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of fusion | 5.46 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of vaporization | 398 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar heat capacity | 26.94 J/(mol·K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Vapor pressure

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | +1, +2, +3, +4 (a mildly basic oxide) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | Pauling scale: 1.12 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionization energies |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic radius | empirical: 181.8 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | 204±9 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Color lines in a spectral range | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Natural occurrence | primordial | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

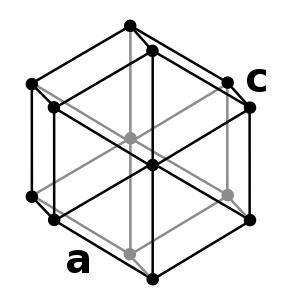

| Crystal structure | double hexagonal close-packed (dhcp) β-Ce | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Crystal structure | face-centered cubic (fcc) γ-Ce | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Speed of sound thin rod | 2100 m/s (at 20 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal expansion | γ, poly: 6.3 µm/(m·K) (at r.t.) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal conductivity | 11.3 W/(m·K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrical resistivity | β, poly: 828 nΩ·m (at r.t.) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic ordering | paramagnetic[3] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic susceptibility | (β) +2450.0·10−6 cm3/mol (293 K)[4] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Young's modulus | γ form: 33.6 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Shear modulus | γ form: 13.5 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bulk modulus | γ form: 21.5 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Poisson ratio | γ form: 0.24 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mohs hardness | 2.5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vickers hardness | 210–470 MPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Brinell hardness | 186–412 MPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS Number | 7440-45-1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Naming | after dwarf planet Ceres, itself named after Roman deity of agriculture Ceres | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Discovery | Martin Heinrich Klaproth, Jöns Jakob Berzelius, Wilhelm Hisinger (1803) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| First isolation | Carl Gustaf Mosander (1838) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Main isotopes of cerium | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Despite always occurring in combination with the other rare-earth elements in minerals such as those of the monazite and bastnäsite groups, cerium is easy to extract from its ores, as it can be distinguished among the lanthanides by its unique ability to be oxidized to the +4 state. It is the most common of the lanthanides, followed by neodymium, lanthanum, and praseodymium. It is the 26th-most abundant element, making up 66 ppm of the Earth's crust, half as much as chlorine and five times as much as lead.

Cerium was the first of the lanthanides to be discovered, in Bastnäs, Sweden, by Jöns Jakob Berzelius and Wilhelm Hisinger in 1803, and independently by Martin Heinrich Klaproth in Germany in the same year. In 1839 Carl Gustaf Mosander became the first to isolate the metal. Today, cerium and its compounds have a variety of uses: for example, cerium(IV) oxide is used to polish glass and is an important part of catalytic converters. Cerium metal is used in ferrocerium lighters for its pyrophoric properties. Cerium-doped YAG phosphor is used in conjunction with blue light-emitting diodes to produce white light in most commercial white LED light sources.

Characteristics

Physical

Cerium is the second element of the lanthanide series. In the periodic table, it appears between the lanthanides lanthanum to its left and praseodymium to its right, and above the actinide thorium. It is a ductile metal with a hardness similar to that of silver.[5] Its 58 electrons are arranged in the configuration [Xe]4f15d16s2, of which the four outer electrons are valence electrons. Immediately after lanthanum, the 4f orbitals suddenly contract and are lowered in energy to the point that they participate readily in chemical reactions; however, this effect is not yet strong enough at cerium and thus the 5d subshell is still occupied.[6] Most lanthanides can use only three electrons as valence electrons, as afterwards the remaining 4f electrons are too strongly bound: cerium is an exception because of the stability of the empty f-shell in Ce4+ and the fact that it comes very early in the lanthanide series, where the nuclear charge is still low enough until neodymium to allow the removal of the fourth valence electron by chemical means.[7]

Four allotropic forms of cerium are known to exist at standard pressure, and are given the common labels of α to δ:[8]

- The high-temperature form, δ-cerium, has a bcc (body-centred cubic) crystal structure and exists above 726 °C.

- The stable form below 726 °C to approximately room temperature is γ-cerium, with an fcc (face-centred cubic) crystal structure.

- The dhcp (double hexagonal close-packed) form β-cerium is the equilibrium structure approximately from room temperature to −150 °C.

- The fcc form α-cerium is stable below about −150 °C; it has a density of 8.16 g/cm3.

- Other solid phases occurring only at high pressures are shown on the phase diagram.

- Both γ and β forms are quite stable at room temperature, although the equilibrium transformation temperature is estimated at around 75 °C.[8]

Cerium has a variable electronic structure. The energy of the 4f electron is nearly the same as that of the outer 5d and 6s electrons that are delocalized in the metallic state, and only a small amount of energy is required to change the relative occupancy of these electronic levels. This gives rise to dual valence states. For example, a volume change of about 10% occurs when cerium is subjected to high pressures or low temperatures. It appears that the valence changes from about 3 to 4 when it is cooled or compressed.[9]

At lower temperatures the behavior of cerium is complicated by the slow rates of transformation. Transformation temperatures are subject to substantial hysteresis and values quoted here are approximate. Upon cooling below −15 °C, γ-cerium starts to change to β-cerium, but the transformation involves a volume increase and, as more β forms, the internal stresses build up and suppress further transformation.[8] Cooling below approximately −160 °C will start formation of α-cerium but this is only from remaining γ-cerium. β-cerium does not significantly transform to α-cerium except in the presence of stress or deformation.[8] At atmospheric pressure, liquid cerium is more dense than its solid form at the melting point.[5][10][11]

Isotopes

Naturally occurring cerium is made up of four isotopes: 136Ce (0.19%), 138Ce (0.25%), 140Ce (88.4%), and 142Ce (11.1%). All four are observationally stable, though the light isotopes 136Ce and 138Ce are theoretically expected to undergo inverse double beta decay to isotopes of barium, and the heaviest isotope 142Ce is expected to undergo double beta decay to 142Nd or alpha decay to 138Ba. Additionally, 140Ce would release energy upon spontaneous fission. None of these decay modes have yet been observed, though the double beta decay of 136Ce, 138Ce, and 142Ce have been experimentally searched for. The current experimental limits for their half-lives are:[12]

- 136Ce: >3.8×1016 y

- 138Ce: >5.7×1016 y

- 142Ce: >5.0×1016 y

All other cerium isotopes are synthetic and radioactive. The most stable of them are 144Ce with a half-life of 284.9 days, 139Ce with a half-life of 137.6 days, and 141Ce with a half-life of 32.5 days. All other radioactive cerium isotopes have half-lives under four days, and most of them have half-lives under ten minutes.[12] The isotopes between 140Ce and 144Ce inclusive occur as fission products of uranium.[12] The primary decay mode of the isotopes lighter than 140Ce is inverse beta decay or electron capture to isotopes of lanthanum, while that of the heavier isotopes is beta decay to isotopes of praseodymium.[12]

The rarity of the proton-rich 136Ce and 138Ce is explained by the fact that they cannot be made in the most common processes of stellar nucleosynthesis for elements beyond iron, the s-process (slow neutron capture) and the r-process (rapid neutron capture). This is so because they are bypassed by the reaction flow of the s-process, and the r-process nuclides are blocked from decaying to them by more neutron-rich stable nuclides. Such nuclei are called p-nuclei, and their origin is not yet well understood: some speculated mechanisms for their formation include proton capture as well as photodisintegration.[13] 140Ce is the most common isotope of cerium, as it can be produced in both the s- and r-processes, while 142Ce can only be produced in the r-process. Another reason for the abundance of 140Ce is that it is a magic nucleus, having a closed neutron shell (it has 82 neutrons), and hence it has a very low cross section towards further neutron capture. Although its proton number of 58 is not magic, it is granted additional stability, as its eight additional protons past the magic number 50 enter and complete the 1g7/2 proton orbital.[13] The abundances of the cerium isotopes may differ very slightly in natural sources, because 138Ce and 140Ce are the daughters of the long-lived primordial radionuclides 138La and 144Nd, respectively.[12]

Chemistry

Cerium tarnishes in air, forming a spalling oxide layer like iron rust; a centimeter-sized sample of cerium metal corrodes completely in about a year.[14] It burns readily at 150 °C to form the pale-yellow cerium(IV) oxide, also known as ceria:[15]

- Ce + O2 → CeO2

This may be reduced to cerium(III) oxide with hydrogen gas.[16] Cerium metal is highly pyrophoric, meaning that when it is ground or scratched, the resulting shavings catch fire.[17] This reactivity conforms to periodic trends, since cerium is one of the first and hence one of the largest lanthanides.[18] Cerium(IV) oxide has the fluorite structure, similarly to the dioxides of praseodymium and terbium. Many nonstoichiometric chalcogenides are also known, along with the trivalent Ce2Z3 (Z = S, Se, Te). The monochalcogenides CeZ conduct electricity and would better be formulated as Ce3+Z2−e−. While CeZ2 are known, they are polychalcogenides with cerium(III): cerium(IV) chalcogenides remain unknown.[16]

_oxide.jpg)

Cerium is a highly electropositive metal and reacts with water. The reaction is slow with cold water but speeds up with increasing temperature, producing cerium(III) hydroxide and hydrogen gas:[15]

- 2 Ce (s) + 6 H2O (l) → 2 Ce(OH)3 (aq) + 3 H2 (g)

Cerium metal reacts with all the halogens to give trihalides:[15]

- 2 Ce (s) + 3 F2 (g) → 2 CeF3 (s) [white]

- 2 Ce (s) + 3 Cl2 (g) → 2 CeCl3 (s) [white]

- 2 Ce (s) + 3 Br2 (g) → 2 CeBr3 (s) [white]

- 2 Ce (s) + 3 I2 (g) → 2 CeI3 (s) [yellow]

Reaction with excess fluorine produces the stable white tetrafluoride CeF4; the other tetrahalides are not known. Of the dihalides, only the bronze diiodide CeI2 is known; like the diiodides of lanthanum, praseodymium, and gadolinium, this is a cerium(III) electride compound.[19] True cerium(II) compounds are restricted to a few unusual organocerium complexes.[20][21]

Cerium dissolves readily in dilute sulfuric acid to form solutions containing the colorless Ce3+ ions, which exist as a [Ce(H2O)9]3+ complexes:[15]

- 2 Ce (s) + 3 H2SO4 (aq) → 2 Ce3+ (aq) + 3 SO2−

4 (aq) + 3 H2 (g)

The solubility of cerium is much higher in methanesulfonic acid.[22] Cerium(III) and terbium(III) have ultraviolet absorption bands of relatively high intensity compared with the other lanthanides, as their configurations (one electron more than an empty or half-filled f-subshell respectively) make it easier for the extra f electron to undergo f→d transitions instead of the forbidden f→f transitions of the other lanthanides.[23] Cerium(III) sulfate is one of the few salts whose solubility in water decreases with rising temperature.[24]

Cerium(IV) aqueous solutions may be prepared by reacting cerium(III) solutions with the strong oxidising agents peroxodisulfate or bismuthate. The value of E⦵(Ce4+/Ce3+) varies widely depending on conditions due to the relative ease of complexation and hydrolysis with various anions, though +1.72 V is a usually representative value; that for E⦵(Ce3+/Ce) is −2.34 V. Cerium is the only lanthanide which has important aqueous and coordination chemistry in the +4 oxidation state.[25][26] Due to ligand-to-metal charge transfer, aqueous cerium(IV) ions are orange-yellow.[27] Aqueous cerium(IV) is metastable in water[28][26] and is a strong oxidising agent that oxidizes hydrochloric acid to give chlorine gas.[25] For example, ceric ammonium nitrate is a common oxidising agent in organic chemistry, releasing organic ligands from metal carbonyls.[29] In the Belousov–Zhabotinsky reaction, cerium oscillates between the +4 and +3 oxidation states to catalyse the reaction.[30] Cerium(IV) salts, especially cerium(IV) sulfate, are often used as standard reagents for volumetric analysis in cerimetric titrations.[31]

The nitrate complex [Ce(NO3)6]2− is the most common cerium complex encountered when using cerium(IV) is an oxidising agent: it and its cerium(III) analogue [Ce(NO3)6]3− have 12-coordinate icosahedral molecular geometry, while [Ce(NO3)5]2− has 10-coordinate bicapped dodecadeltahedral molecular geometry. Cerium nitrates also form 4:3 and 1:1 complexes with 18-crown-6 (the ratio referring to that between cerium and the crown ether). Halogen-containing complex ions such as CeF4−

8, CeF2−

6, and the orange CeCl2−

6 are also known.[25] Organocerium chemistry is similar to that of the other lanthanides, being primarily that of the cyclopentadienyl and cyclooctatetraenyl compounds. The cerium(III) cyclooctatetraenyl compound has the uranocene structure.[32]

Cerium(IV)

Despite the common name of cerium(IV) compounds, the Japanese spectroscopist Akio Kotani wrote "there is no genuine example of cerium(IV)". The reason for this can be seen in the structure of ceria itself, which always contains some octahedral vacancies where oxygen atoms would be expected to go and could be better considered a non-stoichiometric compound with chemical formula CeO2−x. Furthermore, each cerium atom in ceria does not lose all four of its valence electrons, but retains a partial hold on the last one, resulting in an oxidation state between +3 and +4.[33][34] Even supposedly purely tetravalent compounds such as CeRh3, CeCo5, or ceria itself have X-ray photoemission and X-ray absorption spectra more characteristic of intermediate-valence compounds.[35] The 4f electron in cerocene, Ce(C8H8)2, is poised ambiguously between being localized and delocalized and this compound is also considered intermediate-valent.[34]

History

.jpg)

Cerium was discovered in Bastnäs in Sweden by Jöns Jakob Berzelius and Wilhelm Hisinger, and independently in Germany by Martin Heinrich Klaproth, both in 1803.[36] Cerium was named by Berzelius after the dwarf planet Ceres, discovered two years earlier.[36][37] The dwarf planet itself is named after the Roman goddess of agriculture, grain crops, fertility and motherly relationships, Ceres.[36]

Cerium was originally isolated in the form of its oxide, which was named ceria, a term that is still used. The metal itself was too electropositive to be isolated by then-current smelting technology, a characteristic of rare-earth metals in general. After the development of electrochemistry by Humphry Davy five years later, the earths soon yielded the metals they contained. Ceria, as isolated in 1803, contained all of the lanthanides present in the cerite ore from Bastnäs, Sweden, and thus only contained about 45% of what is now known to be pure ceria. It was not until Carl Gustaf Mosander succeeded in removing lanthana and "didymia" in the late 1830s that ceria was obtained pure. Wilhelm Hisinger was a wealthy mine-owner and amateur scientist, and sponsor of Berzelius. He owned and controlled the mine at Bastnäs, and had been trying for years to find out the composition of the abundant heavy gangue rock (the "Tungsten of Bastnäs", which despite its name contained no tungsten), now known as cerite, that he had in his mine.[37] Mosander and his family lived for many years in the same house as Berzelius, and Mosander was undoubtedly persuaded by Berzelius to investigate ceria further.[38][39][40][41]

Occurrence and production

Cerium is the most abundant of all the lanthanides, making up 66 ppm of the Earth's crust; this value is just behind that of copper (68 ppm), and cerium is even more abundant than common metals such as lead (13 ppm) and tin (2.1 ppm). Thus, despite its position as one of the so-called rare-earth metals, cerium is actually not rare at all.[42] Cerium content in the soil varies between 2 and 150 ppm, with an average of 50 ppm; seawater contains 1.5 parts per trillion of cerium.[37] Cerium occurs in various minerals, but the most important commercial sources are the minerals of the monazite and bastnäsite groups, where it makes up about half of the lanthanide content. Monazite-(Ce) is the most common representative of the monazites, with "-Ce" being the Levinson suffix informing on the dominance of the particular REE element representative.[43][44][45] Also the cerium-dominant bastnäsite-(Ce) is the most important of the bastnäsites.[46][43] Cerium is the easiest lanthanide to extract from its minerals because it is the only one that can reach a stable +4 oxidation state in aqueous solution.[47] Because of the decreased solubility of cerium in the +4 oxidation state, cerium is sometimes depleted from rocks relative to the other rare-earth elements and is incorporated into zircon, since Ce4+ and Zr4+ have the same charge and similar ionic radii.[48] In extreme cases, cerium(IV) can form its own minerals separated from the other rare-earth elements, such as cerianite (correctly named cerianite-(Ce)[49][45][43]), (Ce,Th)O2.[50][51][52]

Bastnäsite, LnIIICO3F, is usually lacking in thorium and the heavy lanthanides beyond samarium and europium, and hence the extraction of cerium from it is quite direct. First, the bastnäsite is purified, using dilute hydrochloric acid to remove calcium carbonate impurities. The ore is then roasted in the air to oxidize it to the lanthanide oxides: while most of the lanthanides will be oxidized to the sesquioxides Ln2O3, cerium will be oxidized to the dioxide CeO2. This is insoluble in water and can be leached out with 0.5 M hydrochloric acid, leaving the other lanthanides behind.[47]

The procedure for monazite, (Ln,Th)PO4, which usually contains all the rare earths, as well as thorium, is more involved. Monazite, because of its magnetic properties, can be separated by repeated electromagnetic separation. After separation, it is treated with hot concentrated sulfuric acid to produce water-soluble sulfates of rare earths. The acidic filtrates are partially neutralized with sodium hydroxide to pH 3–4. Thorium precipitates out of solution as hydroxide and is removed. After that, the solution is treated with ammonium oxalate to convert rare earths to their insoluble oxalates. The oxalates are converted to oxides by annealing. The oxides are dissolved in nitric acid, but cerium oxide is insoluble in HNO3 and hence precipitates out.[11] Care must be taken when handling some of the residues as they contain 228Ra, the daughter of 232Th, which is a strong gamma emitter.[47]

Applications

The first use of cerium was in gas mantles, invented by the Austrian chemist Carl Auer von Welsbach. In 1885, he had previously experimented with mixtures of magnesium, lanthanum, and yttrium oxides, but these gave green-tinted light and were unsuccessful.[53] Six years later, he discovered that pure thorium oxide produced a much better, though blue, light, and that mixing it with cerium dioxide resulted in a bright white light.[54] Additionally, cerium dioxide also acts as a catalyst for the combustion of thorium oxide. This resulted in great commercial success for von Welsbach and his invention, and created great demand for thorium; its production resulted in a large amount of lanthanides being simultaneously extracted as by-products.[55] Applications were soon found for them, especially in the pyrophoric alloy known as "mischmetal" composed of 50% cerium, 25% lanthanum, and the remainder being the other lanthanides, that is used widely for lighter flints.[55] Usually, iron is also added to form an alloy known as ferrocerium, also invented by von Welsbach.[56] Due to the chemical similarities of the lanthanides, chemical separation is not usually required for their applications, such as the mixing of mischmetal into steel to improve its strength and workability, or as catalysts for the cracking of petroleum.[47] This property of cerium saved the life of writer Primo Levi at the Auschwitz concentration camp, when he found a supply of ferrocerium alloy and bartered it for food.[57]

Ceria is the most widely used compound of cerium. The main application of ceria is as a polishing compound, for example in chemical-mechanical planarization (CMP). In this application, ceria has replaced other metal oxides for the production of high-quality optical surfaces.[56] Major automotive applications for the lower sesquioxide are as a catalytic converter for the oxidation of CO and NOx emissions in the exhaust gases from motor vehicles,[58][59] Ceria has also been used as a substitute for its radioactive congener thoria, for example in the manufacture of electrodes used in gas tungsten arc welding, where ceria as an alloying element improves arc stability and ease of starting while decreasing burn-off.[60] Cerium(IV) sulfate is used as an oxidising agent in quantitative analysis. Cerium(IV) in methanesulfonic acid solutions is applied in industrial scale electrosynthesis as a recyclable oxidant.[61] Ceric ammonium nitrate is used as an oxidant in organic chemistry and in etching electronic components, and as a primary standard for quantitative analysis.[5][62]

The photostability of pigments can be enhanced by the addition of cerium. It provides pigments with light fastness and prevents clear polymers from darkening in sunlight. Television glass plates are subject to electron bombardment, which tends to darken them by creation of F-center color centers. This effect is suppressed by addition of cerium oxide. Cerium is also an essential component of phosphors used in TV screens and fluorescent lamps.[63][64] Cerium sulfide forms a red pigment that stays stable up to 350 °C. The pigment is a nontoxic alternative to cadmium sulfide pigments.[37]

Cerium is used as alloying element in aluminum to create castable eutectic alloys, Al-Ce alloys with 6–16 wt.% Ce, to which Mg and/or Si can be further added; these alloys have excellent high temperature strength.[65]

Biological role and precautions

| Hazards | |

|---|---|

| GHS pictograms |   |

| GHS Signal word | Danger |

GHS hazard statements |

H228, H302, H312, H332, H315, H319, H335 |

| P210, P261, P280, P301, P312, P330, P305, P351, P338, P370, P378[66] | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

Cerium has no known biological role in humans, but is not very toxic either; it does not accumulate in the food chain to any appreciable extent. Because it often occurs together with calcium in phosphate minerals, and bones are primarily calcium phosphate, cerium can accumulate in bones in small amounts that are not considered dangerous. Cerium, like the other lanthanides, is known to affect human metabolism, lowering cholesterol levels, blood pressure, appetite, and risk of blood coagulation.

Cerium nitrate is an effective topical antimicrobial treatment for third-degree burns,[37][67] although large doses can lead to cerium poisoning and methemoglobinemia.[68] The early lanthanides act as essential cofactors for the methanol dehydrogenase of the methanotrophic bacterium Methylacidiphilum fumariolicum SolV, for which lanthanum, cerium, praseodymium, and neodymium alone are about equally effective.[69]

Like all rare-earth metals, cerium is of low to moderate toxicity. A strong reducing agent, it ignites spontaneously in air at 65 to 80 °C. Fumes from cerium fires are toxic. Water should not be used to stop cerium fires, as cerium reacts with water to produce hydrogen gas. Workers exposed to cerium have experienced itching, sensitivity to heat, and skin lesions. Cerium is not toxic when eaten, but animals injected with large doses of cerium have died due to cardiovascular collapse.[37] Cerium is more dangerous to aquatic organisms, on account of being damaging to cell membranes, but this is not an important risk because it is not very soluble in water.[37]

References

- Meija, Juris; et al. (2016). "Atomic weights of the elements 2013 (IUPAC Technical Report)". Pure and Applied Chemistry. 88 (3): 265–91. doi:10.1515/pac-2015-0305.

- Ground levels and ionization energies for the neutral atoms, NIST

- Lide, D. R., ed. (2005). "Magnetic susceptibility of the elements and inorganic compounds". CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (PDF) (86th ed.). Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-0486-5.

- Weast, Robert (1984). CRC, Handbook of Chemistry and Physics. Boca Raton, Florida: Chemical Rubber Company Publishing. pp. E110. ISBN 0-8493-0464-4.

- Lide, D. R., ed. (2005). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (86th ed.). Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-0486-5.

- Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 1232–5

- Holleman, Arnold Frederik; Wiberg, Egon (2001), Wiberg, Nils (ed.), Inorganic Chemistry, translated by Eagleson, Mary; Brewer, William, San Diego/Berlin: Academic Press/De Gruyter, pp. 1703–5, ISBN 0-12-352651-5

- Koskimaki, D. C.; Gschneidner, K. A.; Panousis, N. T. (1974). "Preparation of single phase β and α cerium samples for low temperature measurements". Journal of Crystal Growth. 22 (3): 225–229. Bibcode:1974JCrGr..22..225K. doi:10.1016/0022-0248(74)90098-0.

- Johansson, Börje; Luo, Wei; Li, Sa; Ahuja, Rajeev (17 September 2014). "Cerium; Crystal Structure and Position in The Periodic Table". Scientific Reports. 4: 6398. Bibcode:2014NatSR...4E6398J. doi:10.1038/srep06398. PMC 4165975. PMID 25227991.

- Stassis, C.; Gould, T.; McMasters, O.; Gschneidner, K.; Nicklow, R. (1979). "Lattice and spin dynamics of γ-Ce". Physical Review B. 19 (11): 5746–5753. Bibcode:1979PhRvB..19.5746S. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.19.5746.

- Patnaik, Pradyot (2003). Handbook of Inorganic Chemical Compounds. McGraw-Hill. pp. 199–200. ISBN 978-0-07-049439-8.

- Audi, G.; Kondev, F. G.; Wang, M.; Huang, W. J.; Naimi, S. (2017). "The NUBASE2016 evaluation of nuclear properties" (PDF). Chinese Physics C. 41 (3): 030001. Bibcode:2017ChPhC..41c0001A. doi:10.1088/1674-1137/41/3/030001.

- Cameron, A. G. W. (1973). "Abundance of the Elements in the Solar System" (PDF). Space Science Reviews. 15 (1): 121–146. Bibcode:1973SSRv...15..121C. doi:10.1007/BF00172440.

- "Rare-Earth Metal Long Term Air Exposure Test". Retrieved 2009-08-08.

- "Chemical reactions of Cerium". Webelements. Retrieved 9 July 2016.

- Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 1238–9

- Gray, Theodore (2010). The Elements. Black Dog & Leventhal Pub. ISBN 978-1-57912-895-1.

- Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 1235–8

- Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 1240–2

- Mikhail N. Bochkarev (2004). "Molecular compounds of "new" divalent lanthanides". Coordination Chemistry Reviews. 248 (9–10): 835–851. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2004.04.004.

- M. Cristina Cassani; Yurii K. Gun'ko; Peter B. Hitchcock; Alexander G. Hulkes; Alexei V. Khvostov; Michael F. Lappert; Andrey V. Protchenko (2002). "Aspects of non-classical organolanthanide chemistry". Journal of Organometallic Chemistry. 647 (1–2): 71–83. doi:10.1016/s0022-328x(01)01484-x.

- Kreh, Robert P.; Spotnitz, Robert M.; Lundquist, Joseph T. (1989). "Mediated electrochemical synthesis of aromatic aldehydes, ketones, and quinones using ceric methanesulfonate". The Journal of Organic Chemistry. 54 (7): 1526–1531. doi:10.1021/jo00268a010.

- Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 1242–4

- Daniel L. Reger; Scott R. Goode; David Warren Ball (2 January 2009). Chemistry: Principles and Practice. Cengage Learning. p. 482. ISBN 978-0-534-42012-3. Retrieved 23 March 2013.

- Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 1244–8

- Vallet, Valérie; Pourret, Olivier; Pédrot, Mathieu; Banik, Nidhu Lal; Réal, Florent; Marsac, Rémi (2017-10-10). "Aqueous chemistry of Ce(IV): estimations using actinide analogues" (PDF). Dalton Transactions. 46 (39): 13553–13561. doi:10.1039/C7DT02251D. ISSN 1477-9234. PMID 28952626.

- Sroor, Farid M.A.; Edelmann, Frank T. (2012). "Lanthanides: Tetravalent Inorganic". Encyclopedia of Inorganic and Bioinorganic Chemistry. doi:10.1002/9781119951438.eibc2033. ISBN 978-1-119-95143-8.

- McGill, Ian. "Rare Earth Elements". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. 31. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. p. 190. doi:10.1002/14356007.a22_607.

- Brener, L.; McKennis, J. S.; Pettit, R. (1976). "Cyclobutadiene in Synthesis: endo-Tricyclo[4.4.0.02,5]deca-3,8-diene-7,10-dione". Org. Synth. 55: 43. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.055.0043.

- B. P. Belousov (1959). "Периодически действующая реакция и ее механизм" [Periodically acting reaction and its mechanism]. Сборник рефератов по радиационной медицине (in Russian). 147: 145.

- Gschneidner K.A., ed. (2006). "Chapter 229: Applications of tetravalent cerium compounds". Handbook on the Physics and Chemistry of Rare Earths, Volume 36. The Netherlands: Elsevier. pp. 286–288. ISBN 978-0-444-52142-2.

- Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 1248–9

- Sella, Andrea. "Chemistry in its element: cerium". 2016. Retrieved 25 July 2016.

- Schelter, Eric J. (20 March 2013). "Cerium under the lens". Nature Chemistry. 5 (4): 348. Bibcode:2013NatCh...5..348S. doi:10.1038/nchem.1602. PMID 23511425.

- Krill, G.; Kappler, J. P.; Meyer, A.; Abadli, L.; Ravet, M. F. (1981). "Surface and bulk properties of cerium atoms in several cerium intermetallic compounds: XPS and X-ray absorption measurements". Journal of Physics F: Metal Physics. 11 (8): 1713–1725. Bibcode:1981JPhF...11.1713K. doi:10.1088/0305-4608/11/8/024.

- "Visual Elements: Cerium". London: Royal Society of Chemistry. 1999–2012. Retrieved December 31, 2009.

- Emsley, John (2011). Nature's Building Blocks: An A-Z Guide to the Elements. Oxford University Press. pp. 120–125. ISBN 978-0-19-960563-7.

- Weeks, Mary Elvira (1956). The discovery of the elements (6th ed.). Easton, PA: Journal of Chemical Education.

- Weeks, Mary Elvira (1932). "The Discovery of the Elements: XI. Some Elements Isolated with the Aid of Potassium and Sodium: Zirconium, Titanium, Cerium and Thorium". The Journal of Chemical Education. 9 (7): 1231–1243. Bibcode:1932JChEd...9.1231W. doi:10.1021/ed009p1231.

- Marshall, James L. Marshall; Marshall, Virginia R. Marshall (2015). "Rediscovery of the elements: The Rare Earths–The Beginnings" (PDF). The Hexagon: 41–45. Retrieved 30 December 2019.

- Marshall, James L. Marshall; Marshall, Virginia R. Marshall (2015). "Rediscovery of the elements: The Rare Earths–The Confusing Years" (PDF). The Hexagon: 72–77. Retrieved 30 December 2019.

- Greenwood and Earnshaw, p. 1294

- Burke, Ernst A.J. (2008). "The use of suffixes in mineral names" (PDF). Elements. 4 (2): 96. Retrieved 7 December 2019.

- "Monazite-(Ce): Mineral information, data and localities". www.mindat.org.

- "CNMNC". nrmima.nrm.se. Archived from the original on 2019-08-10. Retrieved 2018-10-06.

- "Bastnäsite-(Ce): Mineral information, data and localities". www.mindat.org.

- Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 1229–1232

- Thomas, J. B.; Bodnar, R. J.; Shimizu, N.; Chesner, C. A. (2003). "Melt inclusions in zircon". Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry. 53 (1): 63–87. Bibcode:2003RvMG...53...63T. doi:10.2113/0530063.

- "Cerianite-(Ce): Mineral information, data and localities".

- Graham, A. R. (1955). "Cerianite CeO2: a new rare-earth oxide mineral". American Mineralogist. 40: 560–564.

- "Mindat.org - Mines, Minerals and More". www.mindat.org.

- nrmima.nrm.se

- Lewes, Vivian Byam (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 16 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 656.

- Wickleder, Mathias S.; Fourest, Blandine; Dorhout, Peter K. (2006). "Thorium". In Morss, Lester R.; Edelstein, Norman M.; Fuger, Jean (eds.). The Chemistry of the Actinide and Transactinide Elements (PDF). 3 (3rd ed.). Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Springer. pp. 52–160. doi:10.1007/1-4020-3598-5_3. ISBN 978-1-4020-3555-5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-07.

- Greenwood and Earnshaw, p. 1228

- Klaus Reinhardt and Herwig Winkler in "Cerium Mischmetal, Cerium Alloys, and Cerium Compounds" in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry 2000, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi:10.1002/14356007.a06_139

- Wilkinson, Tom (6 November 2009). "Book Of A Lifetime: The Periodic Table, By Primo Levi". The Independent. Retrieved 25 October 2016.

- Bleiwas, D.I. (2013). Potential for Recovery of Cerium Contained in Automotive Catalytic Converters. Reston, Va.: U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Geological Survey.

- "Argonne's deNOx Catalyst Begins Extensive Diesel Engine Exhaust Testing". Argonne National Laboratory.

- AWS D10.11M/D10.11 - An American National Standard - Guide for Root Pass Welding of Pipe Without Backing. American Welding Society. 2007.

- Arenas, L.F.; Ponce de León, C.; Walsh, F.C. (2016). "Electrochemical redox processes involving soluble cerium species" (PDF). Electrochimica Acta. 205: 226–247. doi:10.1016/j.electacta.2016.04.062.

- Gupta, C. K. & Krishnamurthy, Nagaiyar (2004). Extractive metallurgy of rare earths. CRC Press. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-415-33340-5.

- Cerium dioxide Archived 2013-03-02 at the Wayback Machine. nanopartikel.info (2011-02-02)

- Trovarelli, Alessandro (2002). Catalysis by ceria and related materials. Imperial College Press. pp. 6–11. ISBN 978-1-86094-299-0.

- Sims, Zachary (2016). "Cerium-Based, Intermetallic-Strengthened Aluminum Casting Alloy: High-Volume Co-product Development". JOM. 68 (7): 1940–1947. Bibcode:2016JOM....68g1940S. doi:10.1007/s11837-016-1943-9. OSTI 1346625.

- "Cerium GF39030353".

- Dai, Tianhong; Huang, Ying-Ying; Sharma, Sulbha K.; Hashmi, Javad T.; Kurup, Divya B.; Hamblin, Michael R. (2010). "Topical antimicrobials for burn wound infections". Recent Pat Antiinfect Drug Discov. 5 (2): 124–151. doi:10.2174/157489110791233522. PMC 2935806. PMID 20429870.

- Attof, Rachid; Magnin, Christophe; Bertin-Maghit, Marc; Olivier, Laure; Tissot, Sylvie; Petit, Paul (2007). "Methemoglobinemia by cerium nitrate poisoning". Burns. 32 (8): 1060–1061. doi:10.1016/j.burns.2006.04.005. PMID 17027160.

- Pol, Arjan; Barends, Thomas R.M.; Dietl, Andreas; Khadem, Ahmad F.; Eygensteyn, Jelle; Jetten, Mike S.M.; Op Den Camp, Huub J.M. (2013). "Rare earth metals are essential for methanotrophic life in volcanic mudpots". Environmental Microbiology. 16 (1): 255–264. doi:10.1111/1462-2920.12249. PMID 24034209.

Bibliography

- Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.