Catalan independence movement

The Catalan independence movement (Catalan: independentisme català;[lower-alpha 1] Spanish: independentismo catalán) is a social and political movement with roots in Catalan nationalism, which seeks the independence of Catalonia from Spain and, by extension, the independence of North Catalonia from France and that of other Catalan Countries.

The beginnings of popular separatism in Catalonia can be traced back to the mid–19th century, about one century after the loss of the Catalan Constitutions when the country fell under the rule of the Bourbon dynasty and its historical institutions were annulled. Between the 1850s and the 1910s, individuals,[1] organisations[2] and political parties[3] started demanding full independence of Catalonia from Spain.

The organized Catalan independence movement began in 1922, when Francesc Macià founded the political party Estat Català (Catalan State). In 1931, Estat Català and other parties formed Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya (Republican Left of Catalonia; ERC). Macià proclaimed a Catalan Republic in 1931, subsequently accepting autonomy within the Spanish state after negotiations with the leaders of the Second Spanish Republic. During the Spanish Civil War, General Francisco Franco abolished Catalan autonomy in 1938. Following Franco's death in 1975, Catalan political parties concentrated on autonomy rather than independence.

The modern independence movement began in 2010 when the Constitutional Court of Spain ruled that some of the articles of the 2006 Statute of Autonomy—which had been agreed with the Spanish government and passed by a referendum in Catalonia—were unconstitutional, and others were to be interpreted restrictively. Popular protest against the decision quickly turned into demands for independence. Starting with the town of Arenys de Munt, over 550 municipalities in Catalonia held symbolic referendums on independence between 2009 and 2011. All of the towns returned a high "yes" vote, with a turnout of around 30% of those eligible to vote. A 2010 protest demonstration against the court's decision, organised by the cultural organisation Òmnium Cultural, was attended by over a million people. The popular movement fed upwards to the politicians; a second mass protest on 11 September 2012 (the National Day of Catalonia) explicitly called on the Catalan government to begin the process towards independence. Catalan president Artur Mas called a snap general election, which resulted in a pro-independence majority for the first time in the region's history. The new parliament adopted the Catalan Sovereignty Declaration in early 2013, asserting that the Catalan people had the right to decide their own political future.

The Government of Catalonia announced a referendum on the question of statehood, to be held in November 2014. The referendum asked two questions: "Do you want Catalonia to become a state?" and if so, "Do you want this state to be independent?" The Government of Spain referred the proposed referendum to the Constitutional Court, which ruled it unconstitutional. The Government of Catalonia then changed it from a binding referendum to a non-binding "consultation". Despite the Spanish court also banning the non-binding vote, the Catalan self-determination referendum went ahead on 9 November 2014. The result was an 81% vote for "yes-yes", with a turnout of 42%. Mas called another election for September 2015, which he said would be a plebiscite on independence. Although winning the majority of the seats, Pro-independence parties fell just short of a majority of votes (they got 47.8%) in the September election.[4]

The new parliament passed a resolution declaring the start of the independence process in November 2015. The following year, new president Carles Puigdemont, announced a binding referendum on independence. Although deemed illegal by the Spanish government and Constitutional Court, the referendum was held on 1 October 2017. In a vote where the anti-independence parties called for non-participation, results showed a 90% vote in favour of independence, with a turnout of 43%. Based on this referendum result, on 27 October 2017 the Parliament of Catalonia approved a resolution creating an independent Republic unilaterally, by a vote considered illegal by the lawyers of the Parliament of Catalonia for violating the decisions of the Constitutional Court of Spain.[5][6][7]

In the Parliament of Catalonia, parties explicitly supporting independence are Junts per Catalunya (JxC) (which includes Partit Demòcrata Europeu Català (PDeCAT), heir of the former Convergència Democràtica de Catalunya (CDC)); Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya (ERC), and Candidatura d'Unitat Popular (CUP). Parties opposed to the regional independence are Ciutadans (Citizens), People's Party (PP) and the Partit dels Socialistes de Catalunya (PSC). En Comú Podem supports federalism and a legal and agreed referendum.

Its main symbol is the Estelada flag, which has blue and red versions. The Senyera Estelada is a combination of the traditional Catalan Senyera with the Cuban and Puerto Rican revolutionary flags of the early 20th century. Since then, the Estelada has taken many forms, with the Estelada Vermella associated with left-wing Republicanism, the Estelada Blava representing a more conservative mainstream movement, and even the Estelada Blaugrana a flag for Pro-Independence supporters of FC Barcelona.[8]

History

Beginnings

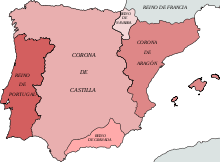

The Principality of Catalonia was an entity of the Crown of Aragon, created by the dynastic union of the County of Barcelona and the Kingdom of Aragon in 1137. In the late 15th century, Aragon united by marriage with the Crown of Castile to form what would later become Kingdom of Spain. Initially, the various entities of the Crown of Aragon, including Catalonia, kept their own fueros (furs in Catalan, laws and customs) and political institutions as guarantee of their sovereignty,[9] for which they fought a civil war during the actual union of the crowns, known as the Catalan Civil War (1462-1472) between foralists and royalists. In 1640, during the Thirty Years War and Franco-Spanish War, Catalan peasants revolted, starting the Reapers' War. The following year, the Catalan government seceded establishing the independence of the Principality, called France for protection and finally named Louis XIII count of Barcelona. After a decade of war, the Spanish Monarchy counter-attacked in 1652 and recovered Barcelona and the rest of Catalonia, except for Roussillon, which was annexed by France. Catalonia retained its fueros.[10][11]

During the War of Spanish Succession, most of the territories of the Crown of Aragon, including Catalonia, fiercely supported Archduke Charles, the Habsburg contender,[12] who swore the Catalan constitutions, against the Bourbon contender,[13] who would later abolish the Catalan constitutions and political institutions through the Nueva Planta Decrees. The Habsburgs' English allies withdrew from the war with the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713, and shortly thereafter, Habsburg troops were evacuated from Italy and from Spain. This left the Catalan government isolated, but it remained loyal to Charles. After a 14-month siege, Barcelona surrendered to a Bourbon army on 11 September 1714. The end of the war was followed by the loss of the fueros of all Crown of Aragon territories, including Catalonia, and the imposition of the Nueva Planta decrees, which centralised Spanish government.[10][13] 11 September, the date of the fall of Barcelona, was commemorated by Catalan nationalists from 1886,[14] and in the 20th century it was chosen as the National Day of Catalonia.[15]

The beginnings of separatism in Catalonia can be traced back to the mid–19th century. The Renaixença (cultural renaissance), which aimed at the revival of the Catalan language and Catalan traditions, led to the development of Catalan nationalism and a desire for independence.[16][17] Between the 1850s and the 1910s, some individuals,[1] organisations[2] and political parties[3] started demanding full independence of Catalonia from Spain.

Twentieth century

The first pro-independence political party in Catalonia was Estat Català (Catalan State), founded in 1922 by Francesc Macià.[18] Estat Català went into exile in France during the dictatorship of Primo de Rivera (1923–1930), launching an unsuccessful uprising from Prats de Molló in 1926.[19] In March 1931, following the overthrow of Primo de Rivera, Estat Català joined with the Partit Republicà Català (Catalan Republican Party) and the political group L'Opinió (Opinion) to form Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya (Republican Left of Catalonia; ERC), with Macià as its first leader.[20] The following month, the ERC achieved a spectacular victory in the municipal elections that preceded the 14 April proclamation of the Second Spanish Republic.[21] Macià proclaimed a Catalan Republic on 14 April, but after negotiations with the provisional government he was obliged to settle for autonomy, under a revived Generalitat of Catalonia.[22] Catalonia was granted a statute of autonomy in 1932, which lasted until the Spanish Civil War. In 1938, General Franco abolished both the Statute of Autonomy and the Generalitat.[10]

A section of Estat Català which had broken away from the ERC in 1936 joined with other groups to found the Front Nacional de Catalunya (National Front of Catalonia; FNC) in Paris in 1940.[18][23] The FNC declared its aim to be "an energetic protest against Franco and an affirmation of Catalan nationalism".[23] Its impact, however, was on Catalan exiles in France rather than in Catalonia itself.[24] The FNC in turn gave rise to the Partit Socialista d'Alliberament Nacional (Socialist Party of National Liberation; PSAN), which combined a pro-independence agenda with a left-wing stance.[25] A split in the PSAN led to the formation of the Partit Socialista d'Alliberament Nacional - Provisional (Socialist Party of National Liberation - Provisional; PSAN-P) in 1974.[26]

Following Franco's death in 1975, Spain moved to restore democracy. A new constitution was adopted in 1978, which asserted the "indivisible unity of the Spanish Nation", but acknowledged "the right to autonomy of the nationalities and regions which form it".[27] Independence parties objected to it on the basis that it was incompatible with Catalan self-determination, and formed the Comité Català Contra la Constitució Espanyola (Catalan Committee Against the Constitution) to oppose it.[26] The constitution was approved in a referendum by 88% of voters in Spain overall, and just over 90% in Catalonia.[28] It was followed by the Statute of Autonomy of Catalonia of 1979, which was approved in a referendum, with 88% of voters supporting it.[29] This led to the marginalisation or disappearance of pro-independence political groups, and for a time the gap was filled by militant groups such as Terra Lliure.[30]

In 1981, a manifesto issued by intellectuals in Catalonia claiming discrimination against the Castilian language, drew a response in the form of published letter, Crida a la Solidaritat en Defensa de la Llengua, la Cultura i la Nació Catalanes ("Call for Solidarity in Defence of the Catalan Language, Culture and Nation"), which called for a mass meeting at the University of Barcelona, out of which a popular movement arose. The Crida organised a series of protests that culminated in a massive demonstration in the Camp Nou on 24 June 1981.[31] Beginning as a cultural organisation, the Crida soon began to demand independence.[32] In 1982, at a time of political uncertainty in Spain, the Ley Orgánica de Armonización del Proceso Autonómico (LOAPA) was introduced in the Spanish parliament, supposedly to "harmonise" the autonomy process, but in reality to curb the power of Catalonia and the Basque region. There was a surge of popular protest against it. The Crida and others organised a huge rally against LOAPA in Barcelona on 14 March 1982. In March 1983, it was held to be ultra vires by the Spanish Constitutional Court.[32] During the 1980s, the Crida was involved in nonviolent direct action, among other things campaigning for labelling in Catalan only, and targeting big companies.[31] In 1983, the Crida's leader, Àngel Colom, left to join the ERC, "giving an impulse to the independentist refounding" of that party.[33]

Second Statute of Autonomy and after

Following elections in 2003, the moderate nationalist Convergència i Unió (CiU), which had governed Catalonia since 1980, lost power to a coalition of left-wing parties composed of the Socialists' Party of Catalonia (PSC), the pro-independence Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya (ERC) and a far-left/Green coalition (ICV-EUiA), headed by Pasqual Maragall. The government produced a draft for a new Statute of Autonomy, which was supported by the CiU and was approved by the parliament by a large majority.[34] The draft statute then had to be approved by the Spanish parliament, which could make changes; it did so, removing clauses on finance and the language, and an article stating that Catalonia was a nation.[35] When the amended statute was put to a referendum on 18 June 2006, the ERC, in protest, called for a "no" vote. The statute was approved, but turnout was only 48.9%.[36] At the subsequent election, the left-wing coalition was returned to power, this time under the leadership of José Montilla.[34]

The conservative Partido Popular, which had opposed the statute in the Spanish parliament, challenged its constitutionality in the Spanish High Court of Justice. The case lasted four years.[37] In its judgement, issued on 18 June 2010, the court ruled that fourteen articles in the statute were unconstitutional, and that 27 others were to be interpreted restrictively. The affected articles included those that gave preference to the Catalan language, freed Catalonia from responsibility for the finances of other autonomous communities, and recognised Catalonia as a nation.[37][38] The full text of the judgement was released on 9 July 2010, and the following day a protest demonstration organised by the cultural organisation Òmnium Cultural was attended by over a million people, and led by José Montilla.[37][38]

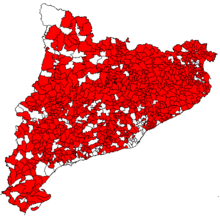

During and after the court case, a series of symbolic referendums on independence were held in municipalities throughout Catalonia. The first of these was in the town of Arenys de Munt on 13 September 2009. About 40% of eligible voters participated, of whom 96% voted for independence.[39] In all, 552 towns held independence referendums between 2009 and 2011.[40] These, together with demonstrations organised by Òmnium Cultural and the Assemblea Nacional Catalana (ANC), represented a "bottom-up" process by which society influenced the political movement for independence.[40] At an institutional level, several municipalities of Catalonia came together to create the Association of Municipalities for Independence, an organisation officially established on 14 December 2011 in Vic which brought local organisations together to further the national rights of Catalonia and promote its right to self-determination.[41] The demonstration of 11 September 2012 explicitly called on the Catalan government to begin the process of secession.[42] Immediately after it, Artur Mas, whose CiU had regained power in 2010, called a snap election for 25 November 2012, and the parliament resolved that a referendum on independence would be held in the life of the next legislature.[43] Although the CiU lost seats to the ERC, Mas remained in power.[43]

2014 Referendum

Mas and ERC leader Oriol Junqueras signed an agreement by which the ERC would support the CiU on sovereignty issues while on other matters it might oppose it. The two leaders drafted the Declaration of Sovereignty and of the Right to Decide of the Catalan People, which was adopted by the parliament at its first sitting in January 2013. The declaration stated that "the Catalan people have, for reasons of democratic legitimacy, the nature of a sovereign political and legal subject", and that the people had the right to decide their own political future.[43]

The Spanish government referred the declaration to the Spanish Constitutional Court, which ruled in March 2014 that the declaration of sovereignty was unconstitutional. The court did not, however, reject the "right to decide", arguing that that right didn't necessarily imply sovereignty or self-determination.[44][45]

On 11 September 2013, an estimated 1.6 million demonstrators formed a human chain, the Catalan Way, from the French border to the regional border with Valencia.[46]

The following month, the CiU, the ERC, the ICV-EUiA and Candidatura d'Unitat Popular (CUP) agreed to hold the independence referendum on 9 November 2014, and that it would ask two questions: "Do you want Catalonia to become a State?" and (if yes) "Do you want this State to be independent?".[47] A further mass demonstration, the Catalan Way 2014, took place on 11 September 2014, when protesters wearing the Catalan colours of yellow and red filled two of Barcelona's avenues to form a giant "V", to call for a vote.[48] Following the Constitutional Court's ruling, the Catalan government changed the vote to a "process of citizen participation" and announced that it would be supervised by volunteers.[47] The Spanish government again appealed to the Constitutional Court, which suspended the process pending the appeal, but the vote went ahead.[49] The result was an 81% vote for yes-yes, but the turnout was only 42%, which could be seen as a majority opposed to both independence and the referendum.[50] Criminal charges were subsequently brought against Mas and others for defying the court order.[49]

In June 2015 the CiU broke up as a result of disagreement between its constituent parties – Convergència Democràtica de Catalunya (CDC) and Unió Democràtica de Catalunya (UDC) – over the independence process. Mas's CDC joined with the ERC and other groups to form Junts pel Sí (Together for "Yes"), which announced that it would declare independence if it won the election scheduled for September.[51] In the September election, Junts pel Sí and the CUP between them won a majority of seats, but fell short of a majority of votes, with just under 48%.[52] On 9 November 2015, the parliament passed a resolution declaring the start of the independence process, proposed by Junts pel Sí and the CUP.[53] In response, Spanish Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy said that the state would "use any available judicial and political mechanism contained in the constitution and in the laws to defend the sovereignty of the Spanish people and of the general interest of Spain", a hint that he would not stop at military intervention.[54] Following prolonged negotiations between Junts pel Sí and the CUP, Mas was replaced as president by Carles Puigdemont in January 2016. Puigdemont, on taking the oath of office, omitted the oath of loyalty to the king and the Spanish constitution, the first Catalan president to do so.[54]

Further pro-independence demonstrations took place in Barcelona in September 2015, and in Barcelona, Berga, Lleida, Salt and Tarragona in September 2016.

2017 Referendum, Declaration of Independence and new regional elections

In late September 2016, Puigdemont told the parliament that a binding referendum on independence would be held in the second half of September 2017, with or without the consent of the Spanish institutions.[55] Puigdemont announced in June 2017 that the referendum would take place on 1 October, and that the question would be, "Do you want Catalonia to become an independent state in the form of a republic?" The Spanish government said in response, "that referendum will not take place because it is illegal."[56][56]

A law creating an independent republic—in the event that the referendum took place and there was a majority "yes" vote, without requiring a minimum turnout—was approved by the Catalan parliament in a session on 6 September 2017.[57][58][59] Opposition parties protested against the bill, calling it "a blow to democracy and a violation of the rights of the opposition", and staged a walkout before the vote was taken.[60] On 7 September, the Catalan parliament passed a "transition law", to provide a legal framework pending the adoption of a new constitution, after similar protests and another walkout by opposition parties.[61][62] The same day, 7 September, the Spanish Constitutional Court suspended the 6 September law while it considered an appeal from Mariano Rajoy, seeking a declaration that it was in breach of the Spanish constitution, meaning that the referendum could not legally go ahead on 1 October.[63][64] The law was finally declared void on 17 October[65] and is also illegal according to the Catalan Statutes of Autonomy which require a two third majority in the Catalan parliament for any change to Catalonia's status.[66][67][68]

The national government seized ballot papers and cell phones, threatened to fine people who manned polling stations up to €300,000, shut down web sites, and demanded that Google remove a voting location finder from the Android app store.[69] Police were sent from the rest of Spain to suppress the vote and close polling locations, but parents scheduled events at schools (where polling places are located) over the weekend and vowed to occupy them to keep them open during the vote.[70] Some election organizers were arrested, including Catalan cabinet officials, while demonstrations by local institutions and street protests grew larger.[71]

The referendum took place on 1 October 2017, despite being suspended by the Constitutional Court, and despite the action of Spanish police to prevent voting in some centres. Images of violence from Spanish riot police beating Catalan voters shocked people and human rights organizations[72] across the globe and resulted in hundreds of injured citizens according to Catalan government officials.[73] Some foreign politicians, including the former Belgian Prime-Minister Charles Michel, condemned violence and called for dialogue.[74] According to the Catalan authorities, 90% of voters supported independence, but turnout was only 43%, and there were reports of irregularities.[75] On 10 October 2017, in the aftermath of the referendum, the President of the Generalitat of Catalonia, Carles Puigdemont, declared the independence of Catalonia but left it suspended. Puigdemont said during his appearance in the Catalan parliament that he assumes, in presenting the results of the referendum, "the people's mandate for Catalonia to become an independent state in the form of a republic", but proposed that in the following weeks the parliament "suspends the effect of the declaration of independence to engage in a dialogue to reach an agreed solution" with the Spanish Government.[75][76]

On 25 October 2017, after the Spanish Governmant had threatened to suspend the Catalan autonomy through article 155 of the Spanish constitution, the UN Independent expert on the promotion of a democratic and equitable international order, Alfred de Zayas, deplored the decision to suspend Catalan autonomy, stating “I deplore the decision of the Spanish Government to suspend Catalan autonomy. This action constitutes retrogression in human rights protection, incompatible with Articles 1, 19, 25 and 27 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). Pursuant to Articles 10(2) and 96 of the Spanish Constitution, international treaties constitute the law of the land and, therefore, Spanish law must be interpreted in conformity with international treaties."[77]

On 27 October 2017 the Catalan Parliament voted in a secret ballot to approve a resolution declaring independence from Spain by a vote of 70–10 in the absence of the constitutionalist deputies, who refused to participate in a vote considered illegal for violating the decisions of the Constitutional Court of Spain.

As a result, the same day (27 October 2017) Article 155 of the Spanish constitution was triggered by the Spanish government; the Catalan government was dismissed and direct rule was imposed from the central government in Madrid.[5][6][7]

Under direct rule from Spain, elections were held in Catalonia on 21 December 2017. The three pro-independence parties retained their control of parliament with a reduced majority of 70 seats and a combined 47.5% of valid votes cast. Ines Arrimadas' anti-independence Ciudadanos party was the most voted party with 25.4% of votes, the first time in Catalan history that a non-nationalist party won most votes and seats in an election. Parties which endorsed the suspension of autonomy by central government represented 43.5% of votes cast and parties which did not include independence in their electoral program amounted to 52.5% of the vote, notably Catcomu-Podem (7.5% of votes and 8 seats), which is opposed to independence but supports a legal referendum and denounced the suspension of autonomy.[78] The excellent performance of the centre-right parties on both sides of the independence debate, Ciudadanos and Juntxcat, and the underperformance of all other parties (notably, left wing parties and the Partido Popular) were the most significant factor in this election result.

The trial of Catalonia independence leaders and October 2019 protests

In 2018 some of the independence leaders were sent to preventive detention without bail, accused of crimes of rebellion, disobedience, and misuse of public funds. Carles Puigdemont and four members of his cabinet fled into self-exile.[79]

12 people were tried by the Supreme Court of Spain, including the previous vice president Oriol Junqueras of the regional government and most of the cabinet as well as political activists Jordi Sànchez and Jordi Cuixart and the former Speaker of the Parliament of Catalonia Carme Forcadell. The trial proceedings officially ended on 12 June 2019. A unanimous verdict by the seven judges that tried the case was made public on 14 October 2019. Nine of the 12 accused received prison sentences for the crimes of sedition; of them, four were also found guilty of misuse of public funds. Their sentences ranged from 9 to 13 years. The remaining three accused were found guilty of disobedience and were sentenced to pay a fine but received no prison term. The court dismissed the charges of rebellion.[80] Some of the defendants of the trial have expressed their intention to appeal to the Constitutional Court of Spain and the European Court of Human Rights.[81][82] The verdict delivered by the Supreme Court sparked multiple protests across the region.

Clashes erupted into open violence, as protesters reacted violently at police efforts to end the demonstration, with some demonstrators setting cars on fire and throwing jars of acid at police officers. The Catalan Law Enforcement agency Mossos d'Esquadra, which had previously been accused of aiding the independence movement, replied by firing tear gas at the demonstrators. The pro-independence speaker of the Catalan Parliament condemned the violent incidents and called for peaceful protests against the ruling.[83] The protests grew larger, as more and more Catalans took to the streets. Some demonstrators attempted to storm buildings belonging to the Spanish Government and clashed with police forces.[84] The Spanish Police announced that 51 protesters had been arrested.[85]

On 17 October, the pro-independence President of the Catalan Autonomous government, Quim Torra, called for an immediate halt to violence and disassociated himself from violent protesters, while at the same time calling for more peaceful protests. Nevertheless, the situation in Barcelona had evolved into open street battles between protesters and police, as both violent demonstrators attacked and provoked police forces, and police officers charged peaceful protesters for their proximity to violent ones.[86]

Several reports[87] claim that the protests and subsequent riots had been infiltrated by Neo-Nazis who used the marches as an opportunity to incite violence.

Shortly thereafter, the Catalan President attempted to rally the crowd by stating that he will push for a new independence referendum as large scale protests continued for the fourth day.[88]

On 18 October, Barcelona became paralyzed, as tens of thousands of peaceful protesters answered the Catalan President's call and rallied in support of the jailed independence leaders.[89] The demonstration grew quickly, with the Barcelona police counting at least 525,000 protesters in the city.[90]

By late 18 October, minor trade unions (Intersindical-CSC and Intersindical Alternativa de Catalunya) linked to pro-independence movement called for a general strike. However, major trade unions (UGT and CCOO) did not endorse the event as well as representatives of the latter contested its very nature as "strike".[91] Five peaceful marches converged on Barcelona's city center, essentially bringing the city to a halt. Protesters further blocked the road on the French-Spanish border. At least 20 other major roads were also blocked. Clashes nevertheless took place, with masked protesters confronting riot police by throwing stones and setting alight rubbish bins.[92] 25,000 university students joined in the protest movement by declaring a peaceful student strike.[93]

As a result of the strike, trains and metro lines saw a reduction to 33% of their usual capacity, while buses saw a reduction to 25-50% of their usual capacity. The roads to the French border remained blocked and all roads leading into Barcelona were also cut. 190 flights in and out of the city were cancelled as a result of the strike. Spanish car manufacturer SEAT further announced a halt in the production of its Martorell plant and most of Barcelona's tourist sites had been closed and occupied by pro-independence demonstrators waving estelada independence flags and posters with pro-independence slogans.[93] The El Clásico football match between FC Barcelona and Real Madrid CF was postponed due to the strike.[94]

By the end of the day, just like the previous days, riots developed in the centre of Barcelona. Masked individuals blocked the boulevard close to the city's police headquarters in Via Laetana. Withdrawn to the vicinity of the Plaça Urquinaona, protesters erected barricades setting trash bins in fire and hurled rubble (debris from broken paving stones) and other solid objects at riot policemen.[95] The riot units responded with non-lethal foam and rubber bullets, tear gas and smoke grenades. The Mossos used for the first time the water cannon trunk acquired in 1994 from Israel in order to make way across the barricades.[96] The clashes spread to cities outside Barcelona, with Spain's acting interior minister stating that 207 policemen had been injured since the start of the protests, while also noting that 128 people had been arrested by the nation's police forces. Miquel Buch, the Catalan Interior Minister, responsible for public order, and a pro-independence politician, called the violence "unprecedented" and distanced himself from the violent events, instead calling for peaceful protests to continue.[80]

On 19 October, following a fifth consecutive night of violence, Catalan President Quim Torra called for talks between the Catalan independence movement and the Spanish government, adding that violence had never been the "flag" of the independence movement.[97] The head of the Spanish Government, Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez, refused to hold talks with the Catalan government, as it deemed the former had not condemned the violence strongly enough. He further categorically rejected the idea of discussing Catalan Independence, stating that it was impossible under Spanish law.[98]

Support for independence

Recently Pro-independence vote evolution

Catalan regional elections, consultation and independence referendum

| Political process | Pro-Independence Votes | % Pro-Independence votes regarding the census | % Pro-Independence votes regarding valid votes | Census | Valid votes[lower-alpha 2] | % of valid votes regarding the census | Pro-Independence political parties | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 Catalan regional election | 282.693 | 5.3 | 9.7 | 5.321.274 | 2.908.290 | 54.7 | ERC (282.693) | CiU (935.756) and ICV (316.222) were pro-sovereignty, they supported the term nation for Catalonia in the Statute |

| 2010 Catalan regional election | 361.928 | 6.7 | 11.9 | 5.363.688 | 3.038.645 | 56.7 | ERC (219.173), SI (102.921), RI (39.834) | CiU (1.202.830), ICV (230.824) |

| 2012 Catalan regional election | 624.559 | 11.5 | 17.4 | 5.413.868 | 3.582.272 | 66.2 | ERC (496.292), CUP (126.435) | CiU (1.116.259), ICV (359.705) and PSC (524.707)[100][101] in favor of a referendum |

| 2014 Catalan self-determination referendum | 1.861.753 | 29.6 | 80.8 | 6.300.000 | 2.305.290 | 36.6 | N/A | Unofficial consultation |

| 2015 Catalan regional election | 1.966.508 | 35.7 | 48.1 | 5.510.853 | 4.092.349 | 74.3 | Junts pel Sí (1.628.714, CDC, ERC, DC, MES), CUP (337.794) | CiU was dissolved before the regional ones of 2015, leaving CDC and UDC. ICV was integrated into Podem-CSQP, these being also in favor of a referendum |

| 2017 Catalan independence referendum | 2.044.038 | 38.3 | 90.2 | 5.343.358 | 2.266.498 | 42.4 | N/A | |

| 2017 Catalan regional election | 2.079.340 | 37.4 | 47.7 | 5.554.455 | 4.357.368 | 78.4 | Junts per Catalunya (948.233), ERC-Cat Sí (935.861), CUP (195.246) | Podem-CatComú (326.360) in favor of a referendum |

The parties explicitly campaigning for independence currently represented in the Catalan Parliament are the Junts per Catalunya coalition (dominated by the PDeCAT, formerly called CDC), the Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya (ERC)—and the Popular Unity Candidacy (CUP). They obtained 34, 32 and 4 seats, respectively, in the Catalan 2017 election (a total of 70 out of 135 seats), with an overall share of 47.7% of the popular vote.[102]

Other smaller pro-independence parties or coalitions, without present representation in any parliament, are Catalan Solidarity for Independence, Estat Català, Endavant, PSAN, Poble Lliure and Reagrupament. There are also youth organisations such as Young Republican Left of Catalonia, Arran, and the student unions SEPC and FNEC.

Spanish general elections in Catalonia

| Political process | Pro-Independence Votes | % Pro-Independence votes regarding the census | % Pro-Independence votes regarding valid votes | Census | Valid votes[lower-alpha 2] | % of valid votes regarding the census | Pro-Independence political parties | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 Spanish general election | 298.139 | 5,6 | 8 | 5.324.909 | 3.723.421 | 69,9 | ERC (298.139) | CiU (779.425) |

| 2011 Spanish general election | 244.854 | 4,5 | 7,1 | 5.396.341 | 3.460.860 | 64,1 | ERC (244.854) | CiU (1.015.691) |

| 2015 Spanish general election | 1.169.035 | 21,2 | 31,1 | 5.516.456 | 3.762.859 | 68,2 | ERC (601.782), CDC-DL (567.253) | En Comú (929.880) |

| 2016 Spanish general election | 1.115.722 | 20,2 | 32,1 | 5.519.882 | 3.477.565 | 63,0 | ERC (632.234), CDC (483.488) | En Comú Podem (853.102) in favor of a referendum |

| April 2019 Spanish general election | 1.634.986 | 29,3 | 39,4 | 5.588.145 | 4.146.563 | 74,2 | ERC (1.020.392), JxCAT (500.787), Front Republicà (113.807) | En Comú Podem (615.665) in favor of a referendum |

| November 2019 Spanish general election | 1.642.063 | 30,6 | 42,5 | 5.370.359[103] | 3.828.394 | 71,3 | ERC (869.934), JxCat (527.375), CUP (244.754) | En Comú Podem (546.733) in favor of a referendum |

Elections to the European Parliament in Catalonia

| Political process | Pro-Independence Votes | % Pro-Independence votes regarding the census | % Pro-Independence votes regarding valid votes | Census | Valid votes[lower-alpha 2] | % of valid votes regarding the census | Pro-Independence political parties | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 European Parliament election | 257.482 | 4,8 | 12,2 | 5.329.787 | 2.116.962 | 39,7 | ERC (249.757), CUP (6.185), EC (1.540) | CiU (369.103), ICV (151.871) |

| 2009 European Parliament election | 186.104 | 3,5 | 9,5 | 5.370.606 | 1.969.043 | 36,7 | ERC (181.213), RC (4.891) | CiU (441.810), ICV (119.755) |

| 2014 European Parliament election | 595.493 | 10,8 | 23,7 | 5.492.297 | 2.513.628 | 45,8 | ERC (595.493), CDC (549.096) | CiU (549.096), ICV (259.152) |

| 2019 European Parliament election | 1.708.396 | 30,3 | 49,8 | 5.645.470 | 3.427.549 | 60,7 | JxCat (981.357), ERC (727.039) | |

Others

.jpeg)

From around 2010, support for Catalan independence broadened from being the preserve of traditional left or far-left Catalan nationalism. Relevant examples are the liberal economists Xavier Sala-i-Martín[105] and Ramon Tremosa Balcells (elected deputy for CiU in the European parliament in the 2009 election), the lawyer and former FC Barcelona president Joan Laporta[106] or the jurist and former member of the Consejo General del Poder Judicial Alfons López Tena.[107]

The Cercle d'Estudis Sobiranistes, a think tank led by the jurists Alfons López Tena and Hèctor López Bofill, was founded in 2007.[108] It affiliated with Solidaritat Catalana per la Independència (Catalan Solidarity for Independence) in 2011.[109]

Other individuals include:

- Joan Massagué, Catalan scientist, director of the Sloan Kettering Institute.[110]

- Pep Guardiola, Catalan football coach of Manchester City FC, former football player and former coach for FC Barcelona and FC Bayern Munich.[111]

- Jordi Galí, Catalan economist, director of the Center for Research in International Economics at UPF.[110]

- Manel Esteller, Catalan scientist, director of the Cancer Epigenetics and Biology Program of the Bellvitge Institute for Biomedical Research and editor-in-chief of the peer-reviewed journal Epigenetics.[110]

- Lluís Llach, Catalan composer and songwriter[112]

- Eduard Punset, Catalan politician, lawyer, economist, and science popularizer.[113]

- Josep Carreras, Catalan tenor singer[114][115]

- Sister Teresa Forcades, Catalan physician and Benedictine nun[116]

- Pilar Rahola, Catalan journalist and writer.

- Miquel Calçada, Catalan journalist[117]

- Joel Joan, Catalan actor[118][119]

- Txarango, Catalan music band[120]

- Xavi Hernández, Catalan professional footballer, he has played in FC Barcelona and Al-Sadd[121]

- Beth, Catalan singer; she was a contestant at Eurovision Song Contest 2003[122]

Opposition to independence

Political parties

All of the Spanish national political parties in Catalonia reject the idea of independence, except Catalonia In Common-We Can (Catalunya En Comú-Podem) which are pro-referendum but have remained neutral on the issue. Together they represent a minority of votes and a minority of seats in the Catalan parliament. Others such as Ciutadans,[123] and the People's Party of Catalonia,[124] which had 25.4% and 4.2% of the vote respectively in the 2017 Catalan regional election, have always opposed the notion of Catalan self-determination. The Socialists' Party (13.9% of vote) opposes independence as well. While some of its members supported the idea of a self-determination referendum up until 2012,[125] the official position as of 2015 is that the Spanish Constitution should be reformed in order to better accommodate Catalonia.[126] A slight majority of voters of left-wing platform Catalonia In Common-We Can (Catalunya En Comú-Podem) (8.94%) reject independence although the party favours a referendum in which it would campaign for Catalonia remaining part of Spain. CDC's Catalanist former-partner Unió came out against independence and fared badly in every subsequent election, eventually disbanding due to bankruptcy in 2017.[127]

Anti-independence movement

On 8 October 2017, Societat Civil Catalana held a rally against Catalan independence; the organisers claimed that over a million people attended, while the Barcelona police force estimated the number at about 300,000.[128] To date this event is the largest pro-Constitution and anti-independence demonstration in the history of Catalonia.[129][130]

On 12 October 2017, 65,000 people, according to the Barcelona police, marched against independence in a smaller demonstration marking the Spanish national day. The turnout was thirteen times more than the prior year and the highest on record in Barcelona's history for this event.[131][132][133]

On 29 October 2017, hundreds of thousands of people demonstrated on the streets of Barcelona in favor of the unity of Spain and celebrating the Spanish government forcing new regional elections in December, in a demonstration called by Societat Civil Catalana. According to the Delegation of the Spanish government in Catalonia the turnout was of 1,000,000 people whereas according to the Barcelona police it was of 300,000 people. Societat Civil Catalana itself estimated the turnout at 1,000,000 people.[134][135][136]

In 2017 the concept of 'Tabarnia' became popular on social media and received widespread media attention. Tabarnia is a fictional region covering urban coastal Catalonia demanding independence from the wider region, should it proceed with independence. Arguments in favor of Tabarnia satirically mirror those in favor of Catalan independence from Spain. Numerous separatists were critical of the concept and responded that the parody unfairly trivializes Catalonia's independence movement, which is based in part on Catalonia's distinct culture and identity.[137][138][139] This proposal, from a platform created in 2011, was shown to map the electoral results of the Catalan regional election of 21 December 2017, which provoked renewed interest. The word 'Tabarnia' went viral on 26 December 2017, reaching worldwide top-trending status with over 648,000 mentions. The first major demonstration in favour of Tabarnia's autonomy from Catalonia took place in Barcelona on the 4th of February 2017, with 15,000 participants according to the Guàrdia Urbana and 200,000 according to organizers.[140]

Other individuals

- José Luis Bonet, Catalan businessman, Chairman of Freixenet[141]

- Juan José Brugera, Catalan businessman, Chairman of Inmobiliaria Colonial[141]

- Isidre Fainé, Catalan banker, Chairman of Caixabank[141]

- José Creuheras, Catalan businessman, Chairman of Planeta Group[141]

- Javier Godó, Catalan businessman, Chairman of Grupo Godó[141]

- Antón Costas, Catalan businessman, Founder of pharmaceutical company Almirall [142]

- Eduardo Mendoza Garriga, Catalan novelist[141]

- Juan Marsé, Catalan novelist, journalist and screenwriter.[141]

- Albert Boadella, Catalan actor, director and playwright[143]

- Mercedes Milá, Catalan television presenter and journalist[144]

- Xavier Sardáes, Catalan presenter and journalist[145]

- Jordi Évole, Catalan presenter and journalist[146]

- Montserrat Caballé, Catalan operatic soprano [144]

- Joan Manuel Serrat, Catalan musician, singer-songwriter, recording artist, and performer [147]

- Estopa, Catalan rock/rumba duo [148]

- Loquillo, Catalan rock singer[149]

- Miguel Poveda, Catalan flamenco singer [141]

- Núria Espert, Catalan theatre and television actress, theatre and opera director[141]

- Javier Cárdenas Catalan singer and television and radio presenter [150]

- Isabel Coixet, Catalan film director [148]

- Santi Millán, Catalan actor, showman and television presenter [148]

- Risto Mejide, Catalan publicist, author, music producer, talent show judge, TV presenter and songwriter[148]

- Susanna Griso, Catalan presenter and journalist[148]

- Jorge Javier Vázquez, Catalan television presenter[148]

- Dani Pedrosa, Catalan Grand Prix motorcycle racer[141]

Polling

Polling institutions

Centre for Opinion Studies

The Centre for Opinion Studies (Centre d'Estudis d'Opinió; CEO) fell under the purview of the Economy Ministry of the Generalitat of Catalonia until early 2011. Since then it has been placed under direct control of the Presidency of the Generalitat and is currently headed by Jordi Argelaguet i Argemí. Since the second quarter of 2011, CEO has conducted polls regarding public sentiments toward independence.

| Date | In favor (%) | Against (%) | Others (%) | Abstain (%) | Do not know (%) | Did not reply (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 2nd series[151] | 42.9 | 28.2 | 0.5 | 23.3 | 4.4 | 0.8 |

| 2011 3rd series[152] | 45.4 | 24.7 | 0.6 | 23.8 | 4.6 | 1.0 |

| 2012 1st series[153] | 44.6 | 24.7 | 1.0 | 24.2 | 4.6 | 0.9 |

| 2012 2nd series[154] | 51.1 | 21.1 | 1.0 | 21.1 | 4.7 | 1.1 |

| 2012 3rd series[155] | 57.0 | 20.5 | 0.6 | 14.3 | 6.2 | 1.5 |

| 2013 1st series[156] | 54.7 | 20.7 | 1.1 | 17.0 | 5.4 | 1.0 |

| 2013 2nd series[157] | 55.6 | 23.4 | 0.6 | 15.3 | 3.8 | 1.3 |

| 2014 1st seriesa | – | – | - | - | – | – |

| 2014 2nd series[158] | 44.5 | 45.3 | - | - | 7.5 | 2.8 |

| 2015 1st series[159] | 44.1 | 48.0 | - | - | 6.0 | 1.8 |

| 2015 2nd series[160] | 42.9 | 50.0 | - | - | 5.8 | 1.3 |

| 2015 3rd series[161] | 46.7 | 47.8 | - | - | 3.9 | 1.7 |

| 2016 1st series[162] | 45.3 | 45.5 | - | - | 7.1 | 2.1 |

| 2016 2nd series[163] | 47.7 | 42.4 | - | - | 8.3 | 1.7 |

| 2016 3rd series[164] | 44.9 | 45.1 | - | - | 7.0 | 2.9 |

| 2017 1st series[165] | 44.3 | 48.5 | - | - | 5.6 | 1.6 |

| 2017 2nd series[166] | 41.1 | 49.4 | - | - | 7.8 | 1.7 |

| 2017 3rd series[167] | 48.7 | 43.6 | - | - | 6.5 | 1.3 |

| 2018 1st series[168] | 48.0 | 43.7 | - | - | 5.7 | 2.6 |

| 2018 2nd series[169] | 46.7 | 44.9 | - | - | 6.7 | 1.6 |

| 2019 1st series[170] | 48.4 | 44.1 | - | - | 6.7 | 1.6 |

| 2019 2nd series[171] | 44.0 | 48.3 | - | - | 5.5 | 2.1 |

a The question was not asked in this survey; instead the two part question was asked (see below).

CEO likewise conducted polls in the 1st and 2nd series of 2014 based on the 9N independence referendum format. The questions and choices involved were:

- Do you want Catalonia to become a State? (Yes/No)

- If the answer for question 1 is in the affirmative: Do you want this State to be independent? (Yes/No)

| Date | Yes + Yes (%) | Yes + No (%) | No (%) | Abstain (%) | Others (%) | Do not know/Did not reply (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 1st series[172] | 47.1 | 8.6 | 19.3 | 11.1 | 2.7 | 11.2 |

| 2014 2nd series[158] | 49.4 | 12.6 | 19.7 | 6.9 | 6.2 | 3.3 |

In addition, CEO performs regular polls studying opinion of Catalan citizens regarding Catalonia's political status within Spain. The following table contains the answers to the question "Which kind of political entity should Catalonia be with respect to Spain?":[173]

| Date | Independent state (%) | Federal state within Spain (%) | Autonomous community within Spain (%) | Region within Spain (%) | Do not know (%) | Did not reply (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| June 2005 | 13.6 | 31.3 | 40.8 | 7.0 | 6.2 | 1.1 |

| November 2005 | 12.9 | 35.8 | 37.6 | 5.6 | 6.9 | 1.2 |

| March 2006 | 13.9 | 33.4 | 38.2 | 8.1 | 5.1 | 1.2 |

| July 2006 | 14.9 | 34.1 | 37.3 | 6.9 | 6.1 | 0.7 |

| October 2006 | 14.0 | 32.9 | 38.9 | 8.3 | 5.1 | 0.8 |

| November 2006 | 15.9 | 32.8 | 40.0 | 6.8 | 3.7 | 0.8 |

| March 2007 | 14.5 | 35.3 | 37.0 | 6.1 | 4.9 | 2.2 |

| July 2007 | 16.9 | 34.0 | 37.3 | 5.5 | 5.4 | 1.0 |

| October 2007 | 18.5 | 34.2 | 35.0 | 4.7 | 6.0 | 1.5 |

| December 2007 | 17.3 | 33.8 | 37.8 | 5.1 | 5.0 | 1.0 |

| January 2008 | 19.4 | 36.4 | 34.8 | 3.8 | 4.1 | 1.6 |

| May 2008 | 17.6 | 33.4 | 38.9 | 5.1 | 4.3 | 0.7 |

| July 2008 | 16.1 | 34.7 | 37.0 | 6.1 | 5.2 | 0.9 |

| November 2008 | 17.4 | 31.8 | 38.3 | 7.1 | 4.2 | 1.2 |

| February 2009[174] | 16.1 | 35.2 | 38.6 | 4.5 | 3.6 | 2.0 |

| May 2009[175] | 20.9 | 35.0 | 34.9 | 4.4 | 3.0 | 1.7 |

| July 2009[176] | 19.0 | 32.2 | 36.8 | 6.2 | 4.2 | 1.6 |

| December 2009[177] | 21.6 | 29.9 | 36.9 | 5.9 | 4.1 | 1.6 |

| 2010 1st series[178] | 19.4 | 29.5 | 38.2 | 6.9 | 4.4 | 1.6 |

| 2010 2nd series[179] | 21.5 | 31.2 | 35.2 | 7.3 | 4.0 | 0.7 |

| 2010 3rd series[180] | 24.3 | 31.0 | 33.3 | 5.4 | 4.9 | 1.0 |

| 2010 4th series[181] | 25.2 | 30.9 | 34.7 | 5.9 | 2.7 | 0.7 |

| 2011 1st series[182] | 24.5 | 31.9 | 33.2 | 5.6 | 3.5 | 1.3 |

| 2011 2nd series[151] | 25.5 | 33.0 | 31.8 | 5.6 | 3.4 | 0.8 |

| 2011 3rd series[152] | 28.2 | 30.4 | 30.3 | 5.7 | 3.9 | 1.5 |

| 2012 1st series[153] | 29.0 | 30.8 | 27.8 | 5.2 | 5.4 | 1.8 |

| 2012 2nd series[154] | 34.0 | 28.7 | 25.4 | 5.7 | 5.0 | 1.3 |

| 2012 3rd series[155] | 44.3 | 25.5 | 19.1 | 4.0 | 4.9 | 2.2 |

| 2013 1st series[156] | 46.4 | 22.4 | 20.7 | 4.4 | 4.9 | 1.2 |

| 2013 2nd series[157] | 47.0 | 21.2 | 22.8 | 4.6 | 3.5 | 0.9 |

| 2013 3rd series[183] | 48.5 | 21.3 | 18.6 | 5.4 | 4.0 | 2.2 |

| 2014 1st series[172] | 45.2 | 20.0 | 23.3 | 2.6 | 6.9 | 2.0 |

| 2014 2nd series[158] | 45.3 | 22.2 | 23.4 | 1.8 | 6.5 | 0.9 |

| 2015 1st series[159] | 39.1 | 26.1 | 24.0 | 3.4 | 5.3 | 2.0 |

| 2015 2nd series[160] | 37.6 | 24.0 | 29.3 | 4.0 | 3.9 | 1.1 |

| 2015 3rd series[161] | 41.1 | 22.2 | 27.4 | 3.7 | 4.2 | 1.4 |

| 2016 1st series[162] | 38.5 | 26.3 | 25.1 | 4.1 | 4.5 | 1.5 |

| 2016 2nd series[163] | 41.6 | 20.9 | 26.5 | 4.0 | 5.6 | 1.3 |

| 2016 3rd series[164] | 38.9 | 23.2 | 24.1 | 5.7 | N/A | N/A |

| 2016 4th series[184] | 36.1 | 29.2 | 23.6 | 4.5 | 3.4 | 3.2 |

| 2017 1st series[165] | 37.3 | 21.7 | 28.5 | 7.0 | 3.8 | 1.6 |

| 2017 2nd series[166] | 34.7 | 21.7 | 30.5 | 5.3 | 6.1 | 1.7 |

| 2017 3rd series[167] | 40.2 | 21.9 | 27.4 | 4.6 | 4.7 | 1.2 |

| 2018 1st series[168] | 40.8 | 22.4 | 24.0 | 6.3 | 4.6 | 2.0 |

| 2018 2nd series[169] | 38.8 | 22.4 | 25.5 | 7.8 | 4.4 | 1.1 |

| 2019 1st series[170] | 39.7 | 21.5 | 26.3 | 5.9 | 4.7 | 1.9 |

| 2019 2nd series[171] | 34.5 | 24.5 | 27.0 | 7.8 | 4.6 | 1.6 |

Social and Political Sciences Institute of Barcelona

The Political Sciences Institute of Barcelona (Institut de Ciències Polítiques i Socials; ICPS) performed an opinion poll annually from 1989, which sometimes included a section on independence. The results are in the following table:[185]

| Year | Support (%) | Against (%) | Indifferent (%) | Did not reply (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1991 | 35 | 50 | 11 | 4 |

| 1992 | 31 | 53 | 11 | 5 |

| 1993 | 37 | 50 | 9 | 5 |

| 1994 | 35 | 49 | 14 | 3 |

| 1995 | 36 | 52 | 10 | 3 |

| 1996 | 29 | 56 | 11 | 4 |

| 1997 | 32 | 52 | 11 | 5 |

| 1998 | 32 | 55 | 10 | 3 |

| 1999 | 32 | 55 | 10 | 3 |

| 2000 | 32 | 53 | 13 | 3 |

| 2001 | 33 | 55 | 11 | 1 |

| 2002 | 34 | 52 | 12 | 1 |

| 2003[a] | 43 | 43 | 12 | 1 |

| 2004[a] | 39 | 44 | 13 | 3 |

| 2005 | 36 | 44 | 15 | 6 |

| 2006 | 33 | 48 | 17 | 2 |

| 2007 | 31.7 | 51.3 | 14.1 | 2.9 |

| 2011 | 41.4 | 22.9 | 26.5 | 9.2 |

a telephonic instead of door-to-door interview

Newspaper polls

Catalan newspapers El Periódico and La Vanguardia also published surveys up to 2013.

El Periódico

| Date | Yes (%) | No (%) | Others (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| October 2007[186] | 33.9 | 43.9 | 22.3 |

| December 2009[187] | 39.0 | 40.6 | 20.4 |

| June 2010[188] | 48.1 | 35.5 | 16.6 |

| January 2012[189] | 53.6 | 32.0 | 14.4 |

| September 2012[190] | 46.4 | 22.0 | 25.7 |

| November 2012[191] | 50.9 | 36.9 | 12.2 |

| November 2012[a][191] | 40.1 | 47.8 | 12.1 |

| May 2013[192] | 57.8 | 36.0 | 6.3 |

a The same poll, but asking what would be the case if a yes vote would imply leaving the EU

La Vanguardia

| Date | Yes (%) | No (%) | Others (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| November 2009[193] | 35 | 46 | 19 |

| March 2010[194] | 36 | 44 | 20 |

| May 2010[195] | 37 | 41 | 22 |

| July 2010[196] | 47 | 36 | 17 |

| September 2010[197] | 40 | 45 | 15 |

| April 2011[198] | 34 | 30 | 35 |

| September 2012[199] | 54.8 | 33.5 | 10.16 |

| December 2013[200] | 44.9 | 45 | 10.1 |

Long-term prospects

Under Spanish law, lawfully exiting Spain would require the Spanish parliament to amend the constitution.[201] It may be difficult for an independent Catalonia to gain international recognition; for example, many countries fail to recognize Kosovo, despite Kosovo having a strong humanitarian claim to independence.[202][203] Most of Catalonia's foreign exports go to the European Union; Catalonia would need Spain's permission if it wishes to eventually re-enter the EU following secession.[204][205][206] Catalonia already runs its own police, schools, healthcare, transport, agriculture, environment policy, municipal governments; other institutions, such as a central bank and a revenue collection service, would have to be rebuilt, possibly losing existing economies of scale.[204][205] Accounting measures vary, but the BBC and The Washington Post cite estimates that in 2014 Catalonians may have paid about 10 billion Euros (or about US$12 billion) more in taxes to the State than what it received in exchange.[204][207][208] As of 2014, an independent Catalonia would be the 34th largest economy in the world.[209] Should Catalonia secede from Spain, some residents of Val d'Aran (population 10,000) have stated they might break away from Catalonia,[210][211] although others state that the local identity has only been recognised by the Catalan Government, something the Spanish State never did.[211]

Criticism

Opponents of Catalan independence have accused the movement of racism or elitism, and argue that the majority of the Catalan public does not support independence.[212] In an op-ed for the Guardian Aurora Nacarino-Brabo and Jorge San Miguel Lobeto, two political scientists affiliated with the anti-independence Ciutadans Spanish nationalist party, disputed the claim that Catalonia has been oppressed or excluded from Spanish politics. They argued that the independence movement is "neither inclusive nor progressive", and criticised nationalists for excluding the Spanish speaking population of Catalonia, and resorting to what they argue are appeals to ethnicity.[213] These criticisms of ethnic-based appeals and exclusion of Spanish speakers have been echoed by other politicians and public figures opposed to independence, such former Spanish Prime Minister Felipe González,[214] and the leader of Ciutadans in Catalonia Inés Arrimadas.[215]

Members of the Catalan independence movement have strongly denied their movement is xenophobic or supremacist and define it as "an inclusive independence movement in which neither the origin nor the language are important".[216] In addition, independence supporters usually allege most far-right and xenophobic groups in Catalonia support Spanish nationalism,[217][218] and usually participate in unionist demonstrations.[219][220][221][222]

On the part of the independence movement, the CDRs (committees for the defence of the republic) were created and organised to hinder police action through "passive resistance." Some Spanish media said that a branch of this group, ERT (technical response teams) are being prosecuted for terrorist offenses. They said that they were found with explosive material and maps of official buildings.[223][224][225] But this has been proven wrong by Spanish justice itself due to the release from prison of the wrongly accused terrorists.[226]

See also

- National and regional identity in Spain

- History of Catalonia

- 2017-18 Spanish constitutional crisis

Notes

- Pronunciation of independentisme català in Catalan: [indəpəndənˈtizmə kətəˈla].

Regional variants:

Northern Catalan: French pronunciation: [ɛ̃dpɑ̃dɑ̃s du katalɑ̃]

Eastern Catalan: [indəpəndənˈtizmə kətəˈɫa]

Western Catalan (including Valencian): [independenˈtizme kataˈla] - White and null votes are subtracted from the number of voters

References

- "Spanish Affairs: The Republicans of Spain (letter)". The New York Times. 7 September 1854. Archived from the original on 14 December 2014. Retrieved 2015-05-31.

- "Current Foreign Topics". The New York Times. 3 August 1886. Archived from the original on 14 December 2014. Retrieved 2015-05-31.

- "Spanish Province Talks Secession: Catalonia, Aroused Against Madrid, Is Agitating for Complete Independence". The New York Times. 18 June 1917. Archived from the original on 14 December 2014. Retrieved 2015-05-31.

- Strange, Hannah (2015-09-27). "Catalan pro-independence parties win majority in regional election". ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 2017-12-23.

- "Un Parlament semivacío consuma en voto secreto la rebelión contra el Estado". El Mundo (in Spanish). 27 October 2017. Retrieved 27 October 2017.

- "Los letrados del Parlament advierten de que la votación de la DUI es ilegal". 20 minutos (in Spanish). 27 October 2017. Retrieved 28 October 2017.

- "PPC, PSC y Ciudadanos abandonarán el Parlament si se vota la resolución de Junts pel Sí y la CUP". La Vanguardia (in Spanish). 27 October 2017. Retrieved 28 October 2017.

- "Understanding Catalan Flags - La Senyera and L'Estelada". Barcelonas. Retrieved 2018-11-20.

- Herr, Richard (1974). An Historical Essay on Modern Spain. University of California Press. p. 41. ISBN 9780520025349. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- Guibernau, Montserrat (2004). Catalan Nationalism: Francoism, Transition and Democracy. Routledge. p. 30. ISBN 978-1134353262. Archived from the original on 27 May 2016. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- "Catalonia, Revolt of (1640–1652)". Encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 14 October 2017.

- Alcoberro, Agustí (October 2010). "The War of the Spanish Succession in the Catalan-speaking Lands". Catalan Historical Review. 3 (3).

- Strubell, Miquel (2011). "The Catalan Language". In Keown, Dominic (ed.). A Companion to Catalan Culture. Tamesis Books. p. 126. ISBN 978-1855662278. Retrieved 6 October 2017.

- Crameri, Kathryn (2008). Catalonia: National Identity and Cultural Policy, 1980-2003. University of Wales Press. p. 160. ISBN 978-0708320136. Retrieved 6 October 2017.

- Balcells, Albert (1996). Catalan Nationalism: Past and Present. Springer. p. 15. ISBN 978-1349242788. Retrieved 6 October 2017.

- Mar-Molinero, Clare; Smith, Angel (1996). Nationalism and the Nation in the Iberian Peninsula: Competing and Conflicting Identities. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 194. ISBN 978-1859731802. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

...which had started with a cultural renaissance (Renaixença) between 1833-1885...

- Holguin, Sandy Eleanor (2002). Creating Spaniards: Culture and National Identity in Republican Spain. Univ of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0299176341. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

What began as a cultural renaissance in the 1840s, ended as a growing call for political autonomy and, eventually, independence

- Romero Salvadó, Francisco J. (2013). Historical Dictionary of the Spanish Civil War. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 123. ISBN 978-0810857841. Retrieved 12 October 2016.

- Harrington, Thomas (2005). "Rapping on the Cast(i)le Gates: Nationalism and Culture-planning in Contemporary Spain". In Moraña, Mabel (ed.). Ideologies of Hispanism. Vanderbilt University Press. p. 124. ISBN 978-0826514721. Retrieved 12 October 2016.

- Lluch, Jaime (2014). Visions of Sovereignty: Nationalism and Accommodation in Multinational Democracies. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 50. ISBN 978-0812209617. Retrieved 12 October 2016.

- Conversi, Daniele (2000). The Basques, the Catalans and Spain: Alternative Routes to Nationalist Mobilisation. University of Nevada Press. pp. 38–9. ISBN 978-0874173628. Retrieved 12 October 2016.

- Costa Carreras, Joan; Yates, Alan (2009). "The Catalan Language". In Costa Carreras, Joan (ed.). The Architect of Modern Catalan: Pompeu Fabra (1868-1948). John Benjamins Publishing. p. 20. ISBN 978-9027232649. Retrieved 12 October 2016.

- Güell Ampuero, Casilda (2006). The Failure of Catalanist Opposition to Franco (1939-1950). Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas. pp. 71–2. ISBN 978-8400084738. Retrieved 12 October 2016.

- Dowling, Andrew (2013). Catalonia Since the Spanish Civil War: Reconstructing the Nation. Sussex Academic Press. p. 152. ISBN 978-1782840176. Retrieved 12 October 2016.

- Lluch (2014), p. 51

- Lluch (2014), p. 52

- Conversi, Daniele (2000). The Basques, the Catalans and Spain: Alternative Routes to Nationalist Mobilisation. University of Nevada Press. pp. 143–4. ISBN 978-0874173628. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- Stepan, Alfred C. (2001). Arguing Comparative Politics. Oxford University Press. p. 204. ISBN 978-0198299974. Retrieved 17 September 2016.

- Conversi (2000), p. 145

- Lluch (2014), p. 53

- Lluch, Jaime (2014). Visions of Sovereignty: Nationalism and Accommodation in Multinational Democracies. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 57. ISBN 978-0812209617. Retrieved 17 September 2016.

- Conversi (2000), pp. 146–7

- Lluch (2014), p. 58

- Cuadras Morató, Xavier (2016). "Introduction". In Cuadras Morató, Xavier (ed.). Catalonia: A New Independent State in Europe?: A Debate on Secession Within the European Union. Routledge. p. 12. ISBN 978-1317580553. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- Crameri, Kathryn (2014). 'Goodbye, Spain?': The Question of Independence for Catalonia. Sussex Academic Press. p. 39. ISBN 978-1782841630. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- Crameri (2014), p. 40

- Guibernau, Montserrat (2012). "From Devolution to Secession: the Case of Catalonia". In Seymour, Michel; Gagnon, Alain-G. (eds.). Multinational Federalism: Problems and Prospects. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 166–7. ISBN 978-0230337114. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- Crameri (2014), p. 44

- Webb, Jason (13 September 2009). "Catalan town votes for independence from Spain". Reuters. Archived from the original on 17 September 2016. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- Guinjoan, Marc; Rodon, Toni (2016). "Catalonia at the crossroads: Analysis of the increasing support for secession". In Cuadras Morató, Xavier (ed.). Catalonia: A New Independent State in Europe?: A Debate on Secession Within the European Union. Routledge. p. 40. ISBN 978-1317580553. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- "El Ple Municipal aprova la proposta de crear una associació per promoure el Dret a Decidir de Catalunya". Ajuntament de Vic (in Catalan). 12 September 2011. Archived from the original on 16 September 2013.

- Crameri (2014), pp. 48–9

- Crameri (2014), p. 50

- Moodrick-Even Khen, Hilly (2016). National Identities and the Right to Self-Determination of Peoples. BRILL. p. 49. ISBN 978-9004294332. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- "Sentencia del Tribunal Supremo" (PDF). Tribunal Constitucional de España. 2014-03-25. Retrieved 2019-11-25.

- Crameri (2014), p. 52

- Guinjoan and Rodon (2016), p. 36

- "Eying Scotland, Spain Catalans seek secession vote". Washington Examiner. Associated Press. 11 September 2014. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- Field, Bonnie N. (2015). "The evolution of sub-state nationalist parties as state-wide parliamentary actors: CiU and the PNV in Spain". In Gillespie, Richard; Gray, Caroline (eds.). Contesting Spain? The Dynamics of Nationalist Movements in Catalonia and the Basque Country. Routledge. p. 117. ISBN 978-1317409489. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- Duerr, Glen M. E. (2015). Secessionism and the European Union: The Future of Flanders, Scotland, and Catalonia. Lexington Books. p. 108. ISBN 978-0739190852. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- Heller, Fernando (22 July 2015). "Catalan separatists send shudders through Madrid". EurActiv. Archived from the original on 5 October 2016. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- Buck, Tobias (27 September 2015). "Independence parties win in Catalonia but fall short of overall victory". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- Buck, Tobias (9 November 2015). "How the Catalonia vote will ramp up tensions with Madrid". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 9 April 2017. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- Simms, Brendan; Guibernau, Montserrat (25 April 2016). "The Catalan cauldron: The prospect of the break-up of Spain poses yet another challenge to Europe". New Statesman. Archived from the original on 4 October 2016. Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- Berwick, Angus; Cobos, Tomás (28 September 2016). "Catalonia to hold independence referendum with or without Spain's consent". Reuters. Archived from the original on 11 October 2016. Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- "Tensions grow in Spain as Catalonia independence referendum confirmed". Telegraph. 9 June 2017. Archived from the original on 10 June 2017. Retrieved 17 June 2017.

- "Catalonia to hold independence vote despite anger in Madrid". The Guardian. 6 September 2017. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

The Catalan government has not set a threshold for minimum turnout, arguing the vote will be binding regardless of the level of participation.

- Jones, Sam (10 September 2017). "Catalans to celebrate their national day with independence protests". Theguardian.com. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- "Catalonia's parliament approves law aimed at independence from Spain". EFE. 7 September 2017. Retrieved 14 October 2017.

- Spongenberg, Helena (7 September 2017). "Catalan authorities call independence vote". EUobserver. Retrieved 23 October 2017.

- "Catalan Parliament passes transition law". Catalan News. 8 September 2017. Retrieved 23 October 2017.

- "Catalan Parliament Passes Bill to Secede from Spain at 1 a.m., after Second Marathon Day in Chamber". The Spain Report. 8 September 2017. Archived from the original on 2017-10-23. Retrieved 23 October 2017.

- "Spain's constitutional court suspends Catalan referendum law: court source". Reuters. 7 September 2017. Retrieved 14 October 2017.

- "Spain Catalonia: Court blocks independence referendum". BBC News. 8 September 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- "Spain just declared Catalan referendum law void". The Independent. 17 October 2017.

- "Catalonia plans an independence vote whether Spain lets it or not". The Economist.

- "Catalan independence referendum". The Daily Star. 10 October 2017.

- Ríos, Pere (6 September 2017). "Las diez claves de la ley del referéndum de Cataluña". El País. Retrieved 30 September 2017.

- Burgen, Stephen (30 September 2017). "Catalonia riven with tension as referendum day arrives". Guardian. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

- Isa Soares, Vasco Cotovio and Laura Smith-Spark, Catalonia on collision course as banned referendum nears, CNN, 29 September 2017

- Camila Domonoske, Spanish Police Detain Catalan Politicians Ahead Of Independence Vote, NPR, 20 September 2017

- "Spain: Police Used Excessive Force in Catalonia". Human Rights Watch. 2017-10-12. Retrieved 2019-08-03.

- "'More than 700 hurt' in Catalonia poll". 2017-10-01. Retrieved 2019-08-03.

- Michel, Charles (2017-10-01). "Violence can never be the answer! We condemn all forms of violence and reaffirm our call for political dialogue #CatalanReferendum #Spain". @charlesmichel. Retrieved 2019-08-03.

- "Catalonia independence declaration signed and suspended". BBC News. 10 October 2017. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- "El president catalán Carles Puigdemont declara la independencia en el Parlament, pero la deja en suspenso (The Catalan President Carles Puigdemont declares the independence in the Parliament, but leaves it suspended)" (in Spanish). El País. 10 October 2017. Retrieved 10 October 2017.

- https://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=22295

- "Elecciones catalanas". El País (in Spanish). 22 December 2017. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- Madrid, Owen Bowcott Sam Jones in (2 March 2018). "Exclusive: Puigdemont vows to lead Catalan government in exile". The Guardian. The Guardian. Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- "Violent clashes rock Barcelona on fifth day of separatist protests". Reuters. 2019-10-18. Retrieved 2019-10-18.

- "UNPO: Catalonia: Spanish Supreme Court to Issue Final Verdict on Catalan Leaders". unpo.org. Retrieved 2019-08-17.

- Jones, Sam (2019-06-12). "Catalan leader defends push for independence on final day of trial". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2019-08-17.

- Madrid, Stephen Burgen Sam Jones in (2019-10-16). "Third night of violence in Barcelona after jailing of Catalan separatists". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2019-10-18.

- "Thousands return to streets in Catalonia protests". 2019-10-15. Retrieved 2019-10-18.

- "Spanish PM: we will not be provoked by Catalonia violence". The Guardian. 2019-10-16.

- "Watch dramatic street battles in Barcelona". BBC News. Retrieved 2019-10-18.

- "Lluvia de golpes de unos neonazis a un antifascista en Barcelona". Última Hora (in Spanish). 2019-10-18. Retrieved 2019-10-28.

- "Catalan leader pushes for second independence vote". 2019-10-17. Retrieved 2019-10-18.

- "Demonstrations paralyse Barcelona". BBC News. Retrieved 2019-10-18.

- Madrid, Stephen Burgen Sam Jones in (2019-10-18). "Barcelona: violence erupts after huge rally over jailing of Catalan separatists". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2019-10-18.

- Farrés, Cristina (19 October 2019). "Indignación sindical: es un 'paro patronal', no una huelga". Crónica Global.

- "Barcelona hit by fresh clashes amid general strike". 2019-10-18. Retrieved 2019-10-18.

- "Barcelona protests: General strike shuts down Catalonia". www.thelocal.es. 2019-10-18. Retrieved 2019-10-18.

- "'Clasico' between Barcelona and Real Madrid postponed". The Sydney Morning Herald. 2019-10-19. Retrieved 2019-10-19.

- "Batalla campal por las calles del centro de Barcelona en la quinta jornada de protestas independentistas". rtve.es. 18 October 2019.

- "Los Mossos utilizan por primera vez la tanqueta de agua para abrir paso entre las barricadas". La Vanguardia. 19 October 2019.

- Madrid, Stephen Burgen Sam Jones in (2019-10-19). "Catalan president calls for talks with Spain's government after unrest". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2019-10-19.

- "Spanish government dismisses call for Catalan talks; police brace for more unrest". Reuters. 2019-10-19. Retrieved 2019-10-19.

- Election data obtained from the website of Instituto de Estadística de Cataluña

- Eleccions al Parlament de Catalunya 2012 (PDF). Programa Electoral PSC. 2012. p. 9.

- Font, Marc (5 November 2019). "L'evolució del PSC: d'incloure el "dret a decidir" al programa electoral a aplaudir que es condemnin els "referèndums il·legals"".

- Medina Ortega, Manuel (2017). "The Political Rights of EU Citizens and the Right of Secession". In Closa, Carlos (ed.). Secession from a Member State and Withdrawal from the European Union: Troubled Membership. Cambridge University Press. p. 142. ISBN 978-1107172197. Retrieved 28 October 2017.

- "November 2019 Spanish general election results". 13 November 2019.

- Elections data obtained from the website of Ministerio del Interior

- "Sala-i-Martin's Independence". Columbia.edu. Archived from the original on 2010-06-26. Retrieved 2009-11-09.

- "Joan Laporta i Estruch (2003-2010) | FCBarcelona.cat". Fcbarcelona.com. Archived from the original on 2008-05-28. Retrieved 2012-09-29.

- "Alfons López Tena: 'Espanya era el país del meu pare, però no és el meu'". Vilaweb.tv. Archived from the original on 2011-10-09. Retrieved 2012-09-29.

- "El Cercle d'Estudis Sobiranistes presenta el manifest fundacional per la independència". TV3. 10 September 2007. Retrieved 28 October 2017.

- "El Cercle d'Estudis Sobiranistes esdevé la fundació de Solidaritat". Vilaweb. 25 November 2011. Retrieved 28 October 2017.

- Joan Massagué o Xavier Estivill, entre los 13 científicos que firman un manifiesto de apoyo a Junts pel Sí http://www.elmundo.es/cataluna/2015/09/22/5601340146163f72078b4578.html

- "Give Catalonia its freedom to vote - by Pep Guardiola, Josep Carreras and other leading Catalans". Independent. 10 October 2014. Archived from the original on 5 October 2016. Retrieved 15 September 2016.

- "Lluis Llach: "El camino español está vallado"... menos para su fundación". Libertad Digital. 5 March 2011. Archived from the original on 3 January 2015.

- "El "sí" y el "no" a la independencia de los famosos". La Vanguardia. 24 October 2017.

- "El Tenor José Carreras ante una cámara: ' Visca Catalunya Lliure' | Intereconomía | 376462". Intereconomia.com. Archived from the original on 2012-04-07. Retrieved 2012-09-29.

- "Carreras, emocionado con la independencia: "Yo no la veré... mis nietos, quizás sí"". En Blau. Retrieved 2019-01-29.

- "Teresa Forcades: "En Catalunya ya no es ridículo decir independencia, se ve posible"". El Periódico. 10 November 2013. Archived from the original on 28 May 2015.

- "Nació Digital: Miquel Calçada: "La dignitat de Catalunya només té un nom: independència"". Naciodigital.cat. Archived from the original on 2012-03-22. Retrieved 2012-09-29.

- "Joel Joan: "España ya no nos da miedo, ya no esperamos los tanques"". Libertad Digital. 18 February 2015. Archived from the original on 23 March 2015.

- "El actor Joel Joan, directo a la independencia de Cataluña: 'España ya no nos da miedo'". Mediterráneo Digital. 18 February 2015. Archived from the original on 30 March 2015.

- "Txarango pone la banda sonora al sí". La Vanguardia. 2017-09-04. Retrieved 2019-01-15.

- Tronchoni, Nadia (2017-10-01). "Xavi: "Lo que está sucediendo en Cataluña es una vergüenza"". El País (in Spanish). ISSN 1134-6582. Retrieved 2019-01-15.

- "Beth, de dar la cara por España en Eurovisión a musa 'indepe' en la Diada". El Español (in Spanish). 2018-09-10. Retrieved 2019-01-15.

- "Ciudadanos - Partido de la Ciudadanía". Ciudadanos-cs.org. Retrieved 2012-10-08.

- "Partit Popular de Catalunya |". Ppcatalunya.com. Archived from the original on 2012-09-28. Retrieved 2012-09-29.

- "L'última batalla dels catalanistes del PSC - Crònica.cat - La informació imprescindible". Cronica.cat. Archived from the original on 2012-03-03. Retrieved 2012-09-29.

- "El PSC renuncia en su programa electoral al derecho a decidir". El Mundo. 2 July 2015. Archived from the original on 9 January 2016. Retrieved 1 November 2015.

- Planas, Pablo (25 March 2017). "Adiós definitivo a Unió, la última víctima de la maldición de Mas". Libertad Digital (in Spanish). Retrieved 28 October 2017.

- "Manifestación Barcelona: 1.000.000 personas según la delegación del Gobierno". La Vanguardia. 2017-10-29. Retrieved 2019-10-06.

- "Más de un millón de personas colapsan Barcelona contra el independentismo". Elmundo.es. 2017-10-08. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- Horowitz, Jason; Kingsley, Patrick (8 October 2017). "'I Am Spanish': Thousands in Barcelona Protest a Push for Independence". Nytimes.com. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- Razón, La (12 October 2017). "Barcelona vive la manifestación más multitudinaria de su historia en un 12-O". Larazon.es. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- "65.000 manifestantes en el 12-O de Barcelona, según la Guardia Urbana, trece veces más que el año anterior". Elmundo.es. 2017-10-12. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- "The Latest: 65,000 recorded at Spanish loyalist rally". Bostonherald.com. Archived from the original on 20 June 2018. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- "Manifestación Barcelona: 1.000.000 personas según la delegación del Gobierno". Lavanguardia.com. 2017-10-29. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- Jones, Sam (29 October 2017). "Catalonia: Madrid warns of Puigdemont jailing as thousands rally for unity". Theguardian.com. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- "Protesters stage big anti-independence rally in Catalonia". Politico.eu. 29 October 2017. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- "Pro-unity Catalans parody secessionists". BBC News. 4 March 2018. Retrieved 5 March 2018.

- "Protesters mock Catalan independence bid with secession call of their own". DW.COM. 2018. Retrieved 5 March 2018.

- "Spanish unionist rally mocks Catalan separatist movement". SFGate. 2018. Retrieved 5 March 2018.

- Blanchar, Clara (2018-03-04). "La plataforma por Tabarnia exhibe músculo y se manifiesta en Barcelona". El País.

- Independenciómetro: famosos a favor o en contra del 'procés' catalán www.vanitatis.elconfidencial.com

- Quiénes son los grandes empresarios catalanes a favor y en contra de la independencia alnavio.com

- Rouco Varela y Albert Boadella, unidos contra la independencia elperiodico.com

- "Famosos a favor y en contra de la independencia". La Nueva España. 27 September 2015. Archived from the original on 29 October 2015. Retrieved 1 November 2015.

- Ya no soy del Barça Archived 2015-11-02 at the Wayback Machine elperiodico.com

- Jordi Évole: "Yo no quiero la independencia de Cataluña" Archived 2016-01-09 at the Wayback Machine youtube

- Serrat: "A Catalunya no le conviene la independencia de España" lavanguardia.com

- "Famosos catalanes que defienden a España… o apoyan la independencia". El Plural.

- Loquillo: "La independencia de Cataluña es una cortina de humo" lasexta.com

- Así desmonta Javier Cárdenas al separatismo gaceta.es

- "Baròmetre d'Opinió Política. 2a onada 2011" (PDF). Centre d'Estudis d'Opinió (in Catalan). 29 June 2011. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- "Baròmetre d'Opinió Política. 3a onada 2011" (PDF). Centre d'Estudis d'Opinió (in Catalan). 25 October 2011. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- "Baròmetre d'Opinió Política. 1a onada 2012" (PDF). Centre d’Estudis d’Opinió (in Catalan). 2 March 2012. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- "Baròmetre d'Opinió Política. 2a onada 2012" (PDF). Centre d’Estudis d’Opinió (in Catalan). 27 June 2012. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- "Baròmetre d'Opinió Política. 3a onada 2012" (PDF). Centre d’Estudis d’Opinió (in Catalan). 8 November 2012. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- "Baròmetre d'Opinió Política. 1a onada 2013" (PDF). Centre d’Estudis d’Opinió (in Catalan). 21 February 2013. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- "Political Opinion Barometer. 2nd wave 2013" (PDF). Centre d’Estudis d’Opinió. 20 June 2013. Retrieved 8 March 2019.