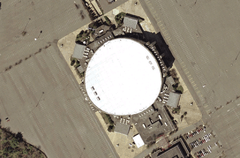

Capital Centre (Landover, Maryland)

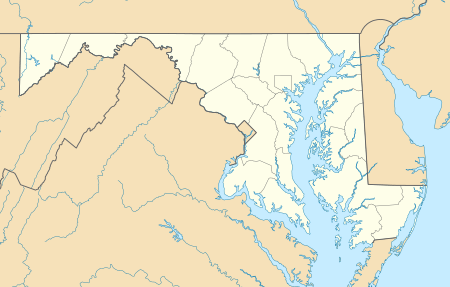

The Capital Centre (later USAir Arena and US Airways Arena) was an indoor arena in the eastern United States, located in Landover, Maryland, a suburb east of Washington, D.C.[5][6]

- Not to be confused with the former Turner's Arena (also known as Capitol Arena) nor with the current Capital One Arena, both in Washington, D.C. proper.

Cap Centre The Cap | |

April 2002, eight months prior to demolition | |

| Former names | USAir Arena (1993–1996) US Airways Arena (1996–1997) |

|---|---|

| Address | 1 Harry S. Truman Drive |

| Location | Landover, Maryland, U.S. |

| Coordinates | 38°54′9″N 76°50′49″W |

| Owner | Washington Sports & Entertainment (Abe Pollin) |

| Operator | Washington Sports & Entertainment (Abe Pollin) |

| Capacity | Basketball: 19,035 (1974–1989) 18,756 (1989–1997) Ice hockey: 18,130 |

| Surface | Multi-surface |

| Construction | |

| Broke ground | August 1972 |

| Opened | December 2, 1973 |

| Closed | 1999 |

| Demolished | December 15, 2002 |

| Construction cost | $18 million[1] ($110 million in 2019 [2]) |

| Architect | Shaver Partnership[3] |

| Structural engineer | Geiger-Berger and Associates[3] |

| General contractor | George Hyman Construction Co.[4] |

| Tenants | |

| Capital/Washington Bullets/Wizards (NBA) (1973–1997) Washington Capitals (NHL) (1974–1997) Georgetown Hoyas (NCAA) (1981–1997) Washington Warthogs (CISL) (1994–1997) Washington/Maryland Commandos (AFL) (1987, 1989) Washington Wave (MILL) (1987–1989) | |

Opened in late 1973, it closed in 1999, and was demolished in 2002.[6] The seating capacity was 18,756 for basketball and 18,130 for hockey. The elevation at street level was approximately 160 feet (50 m) above sea level.

The U.S. Census Bureau defined the land, later occupied by The Boulevard at the Capital Centre,[7] as being in the Mitchellville census-designated place as of the 1990 U.S. Census,[8] while in the 2000 U.S. Census the area was placed in the Lake Arbor CDP.[9][10]

History

Capital Centre was the primary home for the Washington Capitals of the National Hockey League and the Washington Bullets of the National Basketball Association. The Bullets moved to the Washington area from nearby Baltimore, and the Capitals were an expansion team in the arena's second year.

In 1993, the air carrier USAir purchased the naming rights for the building and the arena became known as USAir Arena. When the airline went through its 1996 rebranding and became US Airways, the name of the arena accordingly changed to US Airways Arena.

In 1997, US Airways' naming rights deal came to an end after the now-Wizards and Capitals moved to a new arena, MCI Center (now Capital One Arena) in downtown Washington, and the arena once again became known as Capital Centre. Most TV and radio crews broadcasting from the venue referred to it by its nickname "Cap Centre." Demolished in December 2002, its name continues in The Boulevard at the Capital Centre, the shopping complex on the site.

It was located just outside (east) of the Capital Beltway (Interstate 495) at exit 16, less than a mile (1.6 km) southeast of FedExField, the home of the Washington Redskins of the National Football League, which opened in 1997.

Sports venue

Capital Centre was the home of the Washington Bullets of the NBA from 1973 to 1997, the Washington Capitals of the NHL from 1974 to 1997, and Georgetown University men's basketball from 1981 to 1997. The Washington Wizards were known as the Bullets until 1997, and played the first five home games of the 1997–98 season at the old arena under their new name. All three teams departed for the MCI Center (now Capital One Arena), just north of The Mall in D.C., when it opened on Tuesday, December 2.[11]

Capital Centre hosted its first NBA game exactly 24 years earlier (December 2, 1973), as the Capital Bullets defeated the Seattle SuperSonics, 98–96.[12][13][14] During October and November 1973, the Bullets held their home games at nearby Cole Field House on the campus of the University of Maryland in College Park.

The arena hosted games of three NBA Finals; the first was in 1975, when the favored Bullets were swept by the Golden State Warriors.[15] The Bullets returned to the Finals in 1978 and 1979, in tilts against the Seattle SuperSonics. In 1978, the Bullets won Games 2 and 6 at the Capital Centre on their way to claiming the championship, taking Game 7 in Seattle.[16] The Bullets won the Finals' opener at home in 1979, but then dropped four straight to the Sonics, who celebrated their only NBA title after the Game 5 victory at Capital Centre.[17]

The ACC men's basketball tournament was held at Capital Centre in 1976, 1981, and 1987. It hosted the 1980 NBA All-Star Game, 1982 NHL All-Star Game, and the WWF's Survivor Series 1995. The arena also was home to a few noteworthy NHL playoff games, including the Easter Epic in 1987.

The Washington/Maryland Commandos of the Arena Football League also called the arena home in 1987 and 1989. The Maryland Arrows, Washington Wave, and Washington Power lacrosse teams used the arena, as did The Washington Warthogs professional indoor soccer team.

A boxing World Heavyweight Championship bout took place at the venue in 1976 with Jimmy Young challenging the champion Muhammad Ali. The Friday night fight on April 30 went the full fifteen rounds and was awarded unanimously to a sluggish Ali.[18][19] A year later, 35-year-old Ali defeated Alfredo Evangelista in another unanimous decision to retain the title on May 16, 1977.[20]

Footage of past Washington Bullets games held at the Capital Centre was used in the 1979 comedy film The Fish That Saved Pittsburgh.

Concert venue

The first concert ever held at the Capital Centre was the Allman Brothers Band on December 4, 1973, two nights after the first Bullets' game. They were backed up by the James Montgomery Blues Band, who played from 9 P.M. until midnight. The Allman Brothers played until 3:30 A.M.

The Who played there on two nights later on December 6, as part of the debut of their rock opera Quadrophenia. It was festival seating at the concert and there were no seats on the floor as the venue was newly opened and not finished.[21]

John Denver played his first of ten concerts at the Capital Centre on April 28, 1974 and his last concert there was June 7, 1991. Between those dates, he performed concerts at the Centre in 1982 (2), 1980 (1), 1978 (1), 1976 (2), and 1975 (2).[22][23]

Elvis Presley performed two shows there on Sunday, June 27, 1976, to a total audience of nearly 38,000. Both shows sold out in one day. Ticket prices were $7.50, 10, and 12.50. His last concert at the Capital Centre was on May 22, 1977, during his second-to-last tour, which included 13 other venues. June 26, 1977 in Indianapolis, would be his final concert performance. His only other concert in the Washington, D.C., area was on September 27 and 28, 1974, at nearby University of Maryland's Cole Field House, also in Prince George's County.[24]

The arena was home to several Toys for Tots concerts in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

Frank Sinatra performed for four shows: April 24, 1974 (aud. 16,500), June 20, 1978 (17,000), May 8, 1987 (13,048), and March 31, 1988 (18,146), with Sammy Davis Jr on the "Together Again" tour (Dean Martin left the tour shortly before the concert). The second joint concert with Davis (October 6, 1989) was canceled due to Davis' illness.

The first two volumes of Kiss' retrospective DVD series Kissology included bonus discs of late-1970s shows videotaped at the arena. Kiss first performed on November 30, 1975, supporting their live album Alive (1975); years after that show, it surfaced on various Kiss videos and archives. Kiss returned on December 19, 1976 promoting Rock and Roll Over (1976), and with the Alive II Tour on December 19–20, 1977 supporting their second live album Alive II (1977). Their Dynasty Tour visited the arena on July 7–8, 1979 promoting Dynasty (1979). They returned to the arena after a 13-year absence on October 18, 1992 supporting Revenge (1992) with their Revenge Tour. They returned four years later on October 6–7, 1996 for their Alive/Worldwide Tour.

Chicago's performance recorded live at Capital Centre on June 24–26, 1975, was released in 2011's Chicago XXXIV: Live in '75. After releasing its eighth consecutive gold album in just six years, Chicago embarked upon a massive stadium tour in 1975 that is considered to be one of its finest.

Jethro Tull's performance recorded and filmed live at Capital Centre on November 21, 1977, was released in 2017's Songs From the Wood 40th Anniversary box set. The first four songs' audio was taken from the band's show at the Boston Garden two weeks later because the first reel of the Capital Center audio could not be located.

Concert videos of Blue Öyster Cult from the arena on December 27, 1976 have been released on their Live 1976 DVD and on the Some Enchanted Evening Legacy Edition CD. They were the opening act for Rod Stewart.

The Eagles' performance from March 1977 was released in 2013's History of the Eagles.[25]

Pink Floyd played two shows in June 1975 on their Wish You Were Here Tour, available on bootleg, and then again for four sold-out shows after Roger Waters left in October 1987 during their A Momentary Lapse of Reason Tour.

Led Zeppelin sold out every show they ever booked there. The first concert took place on February 10, 1975; 2 years later in 1977, they sold out 4 dates: May 25, 26, 28 and 30.

Queen performed at the arena on three separate occasions, first during the News of the World Tour in November 1977, then as part of the Jazz Tour the following year. In July 1982, the band returned to the venue for the North American leg of the Hot Space Tour, with Billy Squier as the opening act.[26]

Styx performed here four times between 1978 and 1983. Their April 1981 performance at the venue from the Paradise Theatre tour is available on bootleg.

REO Speedwagon performed here in 1981 and 1982.

Rush performed here on every tour between 1979 and 1991. Their September 1984 performance at the venue from the Grace Under Pressure tour is available on bootleg.

AC/DC performed several concerts of their tours in the arena, such as the Let There Be Rock Tour (1977), If You Want Blood Tour (1979), Back in Black Tour (1980), For Those About to Rock Tour (1981), Flick of the Switch Tour (1983), Blow Up Your Video World Tour (1988) and The Razors Edge World Tour (1990). The shows of December 20–21, 1981 were filmed and several tracks from these shows are included in their DVD set Plug Me In.

A recording of The New Barbarians' concert on May 5, 1979, during the band's only concert tour ever, was released as Buried Alive: Live in Maryland.

The Bee Gees performed two sold-out concerts here on September 24–25, 1979, as part of their Spirits Having Flown Tour.[27]

The Rolling Stones played three sold-out shows at the arena on December 7–9, 1981, in support of Tattoo You, the year's highest-grossing tour, with ticket sales of $50 million. Their 1982 live album Still Life, included three songs taken from the Largo concerts: "Let Me Go" (December 8), "Twenty Flight Rock," and "Going to a Go-Go" (both December 9).

The cult video documentary short Heavy Metal Parking Lot was shot by Jeff Krulik and John Heyn on May 31, 1986, in the arena's parking lot, comically documenting thousands of heavy metal fans as they partied before a Judas Priest concert (with special guests Dokken). (The parking lot itself was divided into four sections, with patriotic emblems, to aid patrons in remembering where they parked after an event: Liberty Bell, Capitol, Eagle, and Stars and Stripes.)

On July 4, 1987, the venue played host to a benefit and tribute concert for Vietnam vets and organized by "Welcome Home", an organization that aids and supports Vietnam vets. The star-studded event included Anita Baker, James Ingram, Crosby, Stills & Nash, The Four Tops, Frankie Valli, James Brown, John Fogerty, John Sebastian, John Ritter, Kris Kristofferson, Linda Ronstadt, Neil Diamond, George Carlin, Richie Havens, John Voight, and Stevie Wonder.[28] The show was broadcast later that evening on HBO.[29]

The Grateful Dead recorded and released three shows performed at the arena: Dick's Picks Volume 20 on September 25, 1976, Terrapin Station (Limited Edition) on March 15, 1990 (on bass guitarist Phil Lesh's 50th birthday), and Spring 1990 on March 16, 1990, the next night.

The Smashing Pumpkins played their last concert with late touring keyboardist Jonathan Melvoin at the arena.

Parliament-Funkadelic headlined numerous sold-out shows at the venue, mainly during the years 1976 to 1983.

Local Washington, D.C.-based go-go bands (such as Rare Essence, Chuck Brown and the Soul Searchers, and E.U.) performed annually at the "Back to School" concerts held at the Capital Center, including the Go Go Live at the Capital Centre concert in 1987.

Michael Jackson held four sold-out concerts at the Capital Centre in 1988 during the Bad tour. The dates were October 13, 17, 18 and 19, 1988.[30]

Madonna's Blond Ambition World Tour included two concerts at the Capital Centre on June 8 and 9, 1990.

Bruce Springsteen held 14 concerts at the Capital Centre between 1978 and 1992:

- August 15 and November 2, 1978 (Darkness Tour)

- November 23 and 24, 1980 and August 5 and 7, 1981 (The River Tour)

- August 25, 26, 28 and 29, 1984 (Born in the U.S.A. Tour)

- April 4 and 5, 1988 (Tunnel of Love Express Tour)

- August 25 and 26, 1992 (Bruce Springsteen 1992–1993 World Tour)

The arena also hosted family-friendly events, such as the Harlem Globetrotters, Circus America, and Ice Capades, as well as numerous graduation ceremonies for high schools in Prince George's County.

Van Halen performed several shows at the arena: their debut tour on August 12, 1978 opening for Ted Nugent, the World Invasion Tour on May 1, 1980 promoting Women and Children First (1980), the Fair Warning Tour on July 28–29, 1981 supporting Fair Warning (1981), and the Hide Your Sheep Tour on October 11–12, 1982 for Diver Down (1982). The second night of the Hide Your Sheep Tour was filmed at the arena. The 1984 Tour on March 25–26, 1984 for 1984 (1984) and the 5150 Tour on August 8–9, 1986 for 5150 (1986). The 5150 Tour was the first to feature Sammy Hagar as David Lee Roth's replacement. Van Halen returned to the arena after a five-year absence on October 17, 1991 supporting their Grammy winning album For Unlawful Carnal Knowledge (1991).

On January 21, 1985, the arena hosted inaugural festivities celebrating President Ronald Reagan's second inauguration. Reagan, Vice President George H. W. Bush, and their wives attended. Bitterly cold weather had forced the cancellation of the previous day's inaugural parade in Washington, D.C. As a result, the alternative indoor event at the Capital Centre afforded the parade's expected participants—including an estimated 9,000 students—an opportunity to perform for the president.[31]

Demolition

The Capital Centre arena was imploded on December 15, 2002. It was replaced by The Boulevard at the Capital Centre, a town center-style shopping mall that opened in Landover in 2003.

Legacy

Opened in late 1973, the Capital Centre was the first indoor arena to have a video replay screen on its center-hung scoreboard. The four-sided projection video screen was known as the "Telscreen" (or "Telescreen") and predated the Diamond Vision video screen at Dodger Stadium by seven years.[32][33] It was also the first indoor arena to be built with luxury boxes,[34] and a computerized turnstile system.

The Centre also had one of the NBA's most notorious fans, Robin Ficker, who for 12 seasons sat behind the visiting team's bench and heckled opposing players.

The Centre had the loudest speaker system in an arena at the time.

The 1993 rename was initially not popular with Washington-area residents.[35]

See also

- Hyperboloid structure

- Tensile architecture

- Thin-shell structure

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Capital Centre. |

References

- Roylance, Frank D. (November 30, 1997). "Capital Centre Blown Away". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved March 27, 2012.

- Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved January 1, 2020.

- http://www.arcaro.org/tension/album/usair.htm

- Clark Construction - Sports (archived)

- "NBA Addresses." Boys' Life. Boy Scouts of America, Inc., December 1993. Volume 83, Number 12 ISSN 0006-8608. p. 80. "U.S. Air Arena 1 Harry S. Truman Drive Landover, MD 20785"

- Augenstein, Neal (April 26, 2017). "Flashback: Before the Capitals, and the birth of the Cap Centre". (Washington, D.C.): WTOP-FM. Retrieved February 6, 2020.

- Bredemeier, Kenneth (June 30, 2003). "The Rejuvenation Of Capital Centre". Washington Post. Retrieved September 9, 2018.

And stark gray concrete outlines of modest buildings have replaced the saddle-shaped Capital Centre arena that stood as a monument to graceless utility for nearly three decades before it was imploded last fall. In its place, and scheduled for a Nov. 15 opening, will be the Boulevard at the Capital Centre,[...]

- "1990 County Block Map" for Prince George's County (see index map). U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved on September 9, 2018. Pages showing what is now Lake Arbor as being in Mitchellville are: 18 and 19.

- "Census 2000 Block Map: Lake Arbor CDP." U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved on September 9, 2018.

- Contact Us." The Boulevard at the Capital Centre. Retrieved on September 9, 2018. "Boulevard at the Capital Centre 900 Capital Centre Boulevard Largo, MD 20774"

- Sheridan, Chris (December 3, 1997). "Simply Wizardry". Free Lance-Star. (Fredericksburg, Virginia). Associated Press. p. A7.

- "Seattle SuperSonics at Capital Bullets Box Score". Basketball Reference. December 2, 1973. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- "Capital ax SuperSonics". Lewiston Morning Tribune. (Idaho). Associated Press. December 3, 1973. p. 13.

- "Bullets 98, SuperSonics 96". Reading Eagle. (Pennsylvania). Associated Press. December 3, 1973. p. 28.

- "Warriors do it their way in 4 straight". Eugene Register-Guard. (Oregon). Associated Press. May 26, 1975. p. 1B.

- Baker, Tony (June 8, 1978). "NBA crown fits Washington, finally". Free Lance-Star. (Fredericksburg, Virginia). Associated Press. p. 10.

- Beard, Gordon (June 2, 1979). "SuperSonics rocket to NBA title". Free Lance-Star. (Fredericksburg, Virginia). Associated Press. p. 10.

- "Sluggish Ali gets by Young". Milwaukee Sentinel. UPI. May 1, 1976. p. 1, part 2.

- "Winner Ali declares he misjudged Young". Spokane Daily Chronicle. (Washington). May 1, 1976. p. 10.

- "Ali's future debatable despite win". Eugene Register-Guard. (Oregon). Associated Press. May 17, 1977. p. 1C.

- The Washington Post, Friday December 7, 1973, page B1 and B19/

- "Capital Centre John Denver". Setlist.fm. Retrieved January 26, 2020.

- "John Denver - Past Events". JohnDenver.com. 2020. Retrieved January 26, 2020.

- Elvis, His Life From A to Z. Wings Books. 1992. pp. 338–340. ISBN 0-517-06634-3.

- "History Of The Eagles". Amazon.com. Retrieved December 26, 2013.

- "25.07.1982 - Concert: Queen live at the Capital Centre, Landover, MD, USA". QueenConcerts.com. Retrieved March 21, 2017.

- ghostsofdc (May 20, 2012). "The Bee Gees Played the Capital Centre in 1979 | Ghosts of DC". Retrieved January 8, 2020.

- Harrington, Richard (July 5, 1987). "A Belated Tribute to Vietnam Veterans". Washington Post.

- Haithman, Diane (July 3, 1987). "A Musical Fourth of July Salute From HBO: All-Star Benefit Concert for Viet Veteran Groups". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved September 15, 2017.

- Harrington, Richard (October 14, 1988). "Michael in motion: Jackson dazzles, surprises at Capital Centre". Washington Post. Retrieved September 11, 2018.

- Clines, Francis X.; Times, Special To the New York (January 21, 1985). "Reagan Sworn for 2d Term; Inaugural Parade Dropped as Bitter Cold Hits Capital". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 20, 2019.

- Cohn, Meredith (October 22, 2002). "Developers break ground for Capital Centre project". Baltimore Sun. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- Starkey, Ted (November 8, 2012). "Remembering the Cap Centre 15 years later". SB Nation. (Washington DC). Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- "Bullets' new arena to have sky boxes". Lewiston Morning Tribune. (Idaho). Associated Press. January 5, 1973. p. 23.

- Beyers, Dan (June 18, 1993). "Calling It USAir Arena, And Not Capital Centre, May Take Time to Fly". Washington Post. Retrieved September 9, 2018.

| Events and tenants | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by first venue |

Home of the Washington Capitals 1974–1997 |

Succeeded by Capital One Arena |

| Preceded by The Forum |

Host of the NHL All-Star Game 1982 |

Succeeded by Nassau Coliseum |