Canis lupus dingo

Canis lupus dingo is a taxonomic rank that includes both the dingo that is native to Australia and the rare New Guinea singing dog that is native to the New Guinea Highlands. It also includes some extinct dogs that were once found in coastal Papua New Guinea and the island of Java in the Indonesian Archipelago. It is a subspecies of Canis lupus. The genetic evidence indicates that the dingo clade originated from East Asian domestic dogs and was introduced through the Malay Archipelago into Australia,[18][19] with a common ancestry between the Australian dingo and the New Guinea singing dog.[19][20]

| Canis lupus dingo | |

|---|---|

| |

| Australian dingo | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Family: | Canidae |

| Genus: | Canis |

| Species: | C. lupus |

| Subspecies: | C. l. dingo |

| Trinomial name | |

| Canis lupus dingo | |

| |

| Distribution of dingoes and hybrids.[4] Distribution in New Guinea unknown. | |

| Synonyms[5] | |

| |

Taxonomic debate – dog, dingo, and New Guinea singing dog

Nomenclature

Zoological nomenclature is a system of naming animals.[21] In 1758, the Swedish botanist and zoologist Carl Linnaeus published in his Systema Naturae the binomial nomenclature – or the two-word naming – of species. Canis is the Latin word meaning "dog",[22] and under this genus he listed the dog-like carnivores including domestic dogs, wolves, and jackals. He classified the domestic dog as Canis familiaris, and on the next page he classified the wolf as Canis lupus.[23] Linnaeus considered the dog to be a separate species from the wolf because of its cauda recurvata - its upturning tail which is not found in any other canid.[24] The International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) advises on the "correct use of the scientific names of animals". The ICZN has entered into its official list: Genus Canis in 1926,[25] Canis familiaris as the type species for genus Canis in 1955,[26] and Canis dingo in 1957.[27][28] These names (such as Canis familiaris and Canis dingo) are then available for use as the correct names for the taxa in question by taxonomists who treat the entities concerned as distinct taxonomic units at species level, rather than as (for example) subtaxa of other species. According to the Principle of Coordination, the same epithets can also be applied at subspecies level, i.e. as the third name in a trinomial name, should the taxonomic treatment being followed prefer such an arrangement.

Taxonomy

Taxonomy classifies organisms together which possess common characteristics. Nomenclature does not determine the rank to be accorded to any assemblage of animals but only its official name.[21] Therefore, zoologists are free to propose which group of animals with similar characteristics that a taxon might belong to. In 1978, a review to reduce the number species listed under genus Canis proposed that "Canis dingo is now generally regarded as a distinctive feral domestic dog. Canis familiaris is used for domestic dogs, although taxonomically it should probably be synonymous with Canis lupus."[29] In 1982, the first edition of Mammal Species of the World included a note under Canis lupus with the comment: "Probably ancestor of and conspecific with the domestic dog, familiaris. Canis familiaris has page priority over Canis lupus, but both were published simultaneously in Linnaeus (1758), and Canis lupus has been universally used for this species".[30]

In 1999, a study of mitochondrial DNA indicated that the domestic dog may have originated from multiple grey wolf populations, with the dingo and New Guinea singing dog "breeds" having developed at a time when human populations were more isolated from each other.[31] In 2003, the ICZN ruled in its Opinion 2027 that the "name of a wild species ... is not invalid by virtue of being predated by the name based on a domestic form". Additionally, the ICZN placed the taxon Canis lupus as a conserved name on the official list under this opinion.[32] This action by the ICZN removed confusion, so that taxonomists would not have to refer to the wolf as Canis familiaris because the domestic form was named before the wild form.

In the third edition of Mammal Species of the World published in 2005, the mammalogist W. Christopher Wozencraft listed under the wolf Canis lupus its wild subspecies, and proposed two additional subspecies: "familiaris Linneaus, 1758 [domestic dog]" and "dingo Meyer, 1793 [domestic dog]", with the comment "Includes the domestic dog as a subspecies, with the dingo provisionally separate – artificial variants created by domestication and selective breeding. Although this may stretch the subspecies concept, it retains the correct allocation of synonyms." Wozencraft included hallstromi – the New Guinea singing dog – as a taxonomic synonym for the dingo. Wozencraft referred to the mDNA study as one of the guides in forming his decision.[5] The inclusion of familiaris and dingo under a "domestic dog" clade has been noted by other mammalogists.[7]

Taxonomic debate

This classification by Wozencraft is debated among zoologists.[33] Mathew Crowther, Stephen Jackson, and Colin Groves disagree with Wozencraft and argue that based on ICZN Opinion 2027, a domestic animal cannot be a subspecies.[2][34] Crowther, Juliet Clutton-Brock and others argue that because the dingo differs from wolves by behavior, morphology, and because the dingo and dog do not fall genetically within the extant wolf clade, that the dingo should be considered the distinct taxon Canis dingo Meyer 1793.[35][33][34][36] Janice Koler-Matznick and others believe that the New Guinea singing dog Canis hallstromi Troughton 1957 should not be classified under Canis lupus dingo on the grounds that it has behavioral, morphological and molecular characteristics that are distinct from the wolf.[37][38][39][40] Jackson and Groves regard the dog Canis familiaris as a taxonomic synonym for the wolf Canis lupus with them both equally ranked at the species level. They also disagree with Crowther, based on the overlap between dogs and dingoes in their morphology, in their ability to easily hybridize with each other, and that they show the signs of domestication by both having a cranium of smaller capacity than their progenitor, the wolf. Given that Canis familiaris Linnaeus 1758 has date priority over Canis dingo Meyer 1793, they regard the dingo as a junior taxonomic synonym for the dog Canis familiaris[2] (i.e. being the equivalent with familiaris named first). Further, the dingo is regarded as a feral dog because it descended from domesticated ancestors.[1][7] Gheorghe Benga and others[41][42][43] support the dingo as a subspecies of the dog Canis familiaris dingo Meyer 1793[10] with the domestic dog being the subspecies Canis familiaris familiaris.[4]

In 2008, the paleontologists Xiaoming Wang and Richard H. Tedford propose that the dog could be taxonomically classified as Canis lupus familiaris under the Biological Species Concept because the dog can interbreed with the gray wolf Canis lupus, and classified as Canis familiaris under the Evolutionary Species Concept because the dog has commenced down a separate evolutionary pathway to the gray wolf.[44]

In 2015, the Taxonomy of Australian Mammals classed the dingo as Canis familiaris.[2] In 2017, a review of the latest scientific information proposes that the dingo and New Guinea singing dog are both types of domestic dog Canis familiaris.[7] The Australian Government's Australian Faunal Directory lists the dingo under Canis familiaris.[8] In 2018, the taxonomic reference Walker's Mammals of the World recognised the dingo as Canis familiaris dingo.[45] The Australian National Kennel Council recognizes a dingo breed standard within its Hounds group.[46]

In 2019, a workshop hosted by the IUCN/SSC Canid Specialist Group considered the New Guinea Singing Dog and the Dingo to be feral dogs Canis familiaris, and therefore should not be assessed for the IUCN Red List.[47]

Genomic evidence

Whole genome sequencing indicates the dog to be a genetically divergent subspecies of the gray wolf,[48] the dog is not a descendant of the extant gray wolf but these are sister taxa which share a common ancestor from a ghost population of wolves that went extinct at the end of the Late Pleistocene,[49] and the dog and the dingo are not separate species.[48] The dingo and the Basenji are basal members of the domestic dog clade.[48][50][49] "The term basal taxon refers to a lineage that diverges early in the history of the group and lies on a branch that originates near the common ancestor of the group."[51] Mitochondrial genome sequences indicates that the dingo falls within the domestic dog clade,[52] and that the New Guinea singing dog is genetically closer to those dingoes that live in southeastern Australia than to those that live in the northwest.[53]

Taxonomic synonyms

%2C_1772.jpg)

A taxonomic synonym is a name that applies to a taxon that now goes by a different name. In 2005, W. Christopher Wozencraft in the third edition of Mammal Species of the World listed under the wolf Canis lupus the taxon dingo along with its proposed taxonomic synonyms:

dingo Meyer, 1793 [domestic dog]; antarticus Kerr, 1792 [suppressed, ICZN, O.451]; australasiae Desmarest, 1820; australiae Gray, 1826; dingoides Matschie, 1915; macdonnellensis Matschie, 1915; novaehollandiae Voigt, 1831; papuensis Ramsay, 1879; tenggerana Kohlbrugge, 1896; hallstromi Troughton, 1957; harappensis Prashad, 1936.[5]

These form the subspecies Canis lupus dingo. Of the ten valid taxa, the majority refer to the Australian dingo, one to the New Guinea singing dog, and three refer to extinct dogs that were once found in the Indonesian archipelago or Southern Asia.

Canis dingo, Australian dingo

For the taxon Canis dingo, the following taxa are regarded as its taxonomic synonyms located in Australia: antarticus [suppressed],[27] Canis familiaris australasiae,[55][56][5] Canis australiae,[55][56][5] Canis dingoides,[56][5] Canis macdonnellensis,[56][5] Canis familiaris novaehollandiae.[5]

In 1768, James Cook took command of a scientific voyage of discovery from Britain to New Holland, which was the name for Australia at that time. In 1770, his ship HMS Endeavour arrived in Botany Bay, which is now part of Sydney. The mission made notes and collected specimens for taking back to Britain. On return to Britain, Joseph Banks commissioned George Stubbs to produce paintings based on his observations, one of which was the "Portrait of a Large Dog from New Holland" completed in 1772.

In 1788, the First Fleet arrived in Botany Bay under the command of Australia's first colonial governor, Arthur Phillip, who took ownership of a dingo[57] and in his journal made a brief description with an illustration of the "Dog of New South Wales".[54] In 1793, based on Phillip's brief description and illustration, the "Dog of New South Wales" was classified by Friedrich Meyer as Canis dingo.[3] Johann Friedrich Blumenbach gathered together a collection from the Cook voyage[58] and in 1797 he also classified the "New Holland dog" as Canis familiaris dingo.[10]

In 1947, a proposal was made to change Meyer's classification Canis dingo after it was discovered that the "New Holland dog" Canis antarticus (Kerr, 1792)[6] had been specified a year earlier in a little-known work.[59] Both Kerr and Meyer had based their classifications on Phillip's brief description and illustration of the "Dog of New South Wales",[34] and therefore there is no type specimen that these classifications were based on.[33] In 1957, the ICZN was asked to suppress the name Canis antarticus on the grounds that Canis dingo was the common name that had been used for over 150 years. The ICZN found in favour of Canis dingo Meyer 1793 and suppressed the name Canis antarticus Kerr 1792.[27]

Canis hallstromi, New Guinea singing dog

The New Guinea singing dog or New Guinea Highland dog Canis hallstromi Troughton 1957. The Australian mammalogist Ellis Troughton classified this rare dog that is native to the New Guinea Highlands on the island of New Guinea.[16]

Canis papuensis, Papua New Guinea

The "Papuan dog" Canis papuensis Maclay 1882. The Russian biologist Nicholas De Miklouho-Maclay compared the dingo with a Papuan dog specimen from Bonga village, 25 km north of Finschhafen, on the Maclay Coast in Papua New Guinea. He noted that compared to the dingo, this dog was smaller, did not have the bushy tail, had some parts of the brain that were comparatively smaller, and was very timid and howled rather than barked. These dogs are sometimes fed by their owners but at other times can found on reefs at low tide hunting for crabs and small fish. At night, along with the pigs, they clean up any refuse left in the village. Rarely do they go hunting with their owners.[60] Jackson and Groves propose that Canis papuensis may refer to feral dogs.[2]

Canis tenggerana, Java

The "Tengger dog" Canis tenggerana Kohlbrugge 1896. The Dutch physician and anthropologist Jacob Kohlbrügge noted this canid while working in the Tennger Mountains in eastern Java.[15] The status of the Tengger dog as being wild or domesticated is not clear. It has been described as a bush-dwelling dog although its morphology shows no wild adaptation, and it has also been described as easy to domesticate.[61] A similar dog existed in the Dieng highlands, and it is assumed that pure populations of these two dogs no longer exist due to crossbreeding with varieties of domestic dogs.[62] Another view is that these dogs were rare at the time of discovery, could not survive on the hot lowlands and therefore could not be bred with local dogs, and shared a similar unique leg structure with the dingo.[63] Jackson and Groves disagree with Wozencraft, and believe that this taxon does not closely resemble the dingo.[2]

Canis harappensis, southern Asia

The "Harapa dog" Canis harappensis Prashad, 1936. The Indian zoologist Baini Prashad noted the remains of a dog that was discovered during excavations at Harappa, in modern Pakistan. The researchers collected a wide variety of ancient domestic animal remains which had been buried for 5,000 years. Also found was a dog skull, however its location and depth was not recorded and its age is not known. It is described as being moderately large in size and with an elongated and pointed snout. It showed a close affinity with the Indian pariah dog, however a comparison of skull morphology showed that the pariah dog skull was closer to the Indian jackal but the Harapa dog was closer to the Indian wolf. It is described as being morphologically similar to Canis tenggerana from Java, and it had earlier been proposed that a population of early dogs had been more widespread across the region.[17] Jackson and Groves disagree with Wozencraft, and believe that this taxon does not closely resemble the dingo.[2]

Archaeological evidence

The oldest reliable date for dog remains found in mainland Southeast Asia is from Vietnam at 4,000 years before present (YBP),[64] and in island southeast Asia from Timor-Leste at 3,075–2,921 YBP.[61] The earliest dingo remains in the Torres Straits date to 2,100 YBP. In New Guinea, the earliest dog remains date to 2,500–2,300 YBP from Caution Bay near Port Moresby but no ancient New Guinea singing dog remains have been found.[1]

The earliest dingo skeletal remains in Australia are estimated at 3,450 YBP from the Mandura Caves on the Nullarbor Plain, south-eastern Western Australia;[1][2] 3,320 YBP from Woombah Midden near Woombah, New South Wales; and 3,170 YBP from Fromme's Landing on the Murray River near Mannum, South Australia.[2] Dingo bone fragments were found in a rock shelter located at Mount Burr, South Australia in a layer that was originally dated 7,000-8,500 YBP.[65] Excavations later indicated that the levels had been disturbed, and the dingo remains "probably moved to an earlier level."[33][66] The dating of these early Australian dingo fossils led to the widely-held belief that dingoes first arrived in Australia 4,000 YBP and then took 500 years to disperse around the continent.[67] However, the timing of these skeletal remains were based on the dating of the sediments in which they were discovered, and not the specimens themselves.[64]

In 2018, the oldest skeletal bones from the Madura Caves were directly carbon dated between 3,348–3,081 YBP, providing firm evidence of the earliest dingo and that dingoes arrived later than had previously been proposed. The next most reliable timing is based on desiccated flesh dated 2,200 YBP from Thylacine Hole, 110 km west of Eucla on the Nullarbor Plain, south-eastern Western Australia. When dingoes first arrived they would have been taken up by Indigenous Australians, who then provided a network for their swift transfer around the continent. Based on the recorded distribution time for dogs across Tasmania and cats across Australia once Indigenous Australians had acquired them, the dispersal of dingoes from their point of landing until they occupied continental Australia is proposed to have taken only 70 years.[64] The red fox is estimated to have dispersed across the continent in only 60–80 years.[67]

Based on a comparison with these early fossils, dingo morphology has not changed over thousands of years. This suggests that there has been no artificial selection over this period and that the dingo represents an early form of dog.[67] They have lived, bred, and undergone natural selection in the wild, isolated from other canines until the arrival of European settlers, resulting in a unique canid.[35][34]

Lineage

At the end of the Last glacial maximum and the associated rise in sea levels, Tasmania became separated from the Australian mainland 12,000 YBP,[68] and New Guinea 6,500[53]–8,500 YBP[53][69] by the inundation of the Sahul Shelf.[70] Fossil remains in Australia date to approximately 3,500 YBP and no dingo remains have been uncovered in Tasmania, therefore the dingo is estimated to have arrived in Australia at a time between 12,000 and 3,500 YBP. To reach Australia through the Malay Archipelago even at the lowest sea level of the Last Glacial Maximum, a journey of at least 50 km over open sea between ancient Sunda and Sahul was necessary, indicating that the dingo arrived by boat.[18]

Studies of the dingo maternal lineage through the use of mitochondrial DNA (mDNA) as a genetic marker indicate that dingoes are descended from a small founding population[71] through a single founding event[18] or no more than a few founding events[20] either 5,400–4,600 YBP or 10,800–4,600 YBP,[18] or 18,300–4,640 YBP,[19] depending on mutation rate assumptions used. They remained isolated from other dogs until the arrival of Europeans.[18][20] However, whole genome sequencing indicates that there was ancient inbreeding in the founding population that first arrived in Australia less than 4,000 YBP.[48]

Ancestors

In 1995, a researcher compared the skull morphology of the dingo to those of other dogs and wolves and concluded that the dingo was a primitive dog that may have evolved from either the Indian wolf (C. l. pallipes) or the Arabian wolf (C. l. arabs).[73] Based on phenotype, the same researcher proposes that in the past, dingoes were widespread across the planet but they had declined due to admixture with domestic dogs. Dingoes were thought to exist in Australia as wild dogs, rare in New Guinea, but common in Sulawesi and in northern and central Thailand. Relic populations were thought to occur in Cambodia, China, India, Indonesia, Lao PDR, Malaysia, Myanmar, Papua New Guinea, Philippines and Vietnam. However, morphological comparisons (based on skull measurements) had not been undertaken on specimens to provide a better understanding.[74] Later DNA studies indicate this proposed wide distribution to be incorrect.

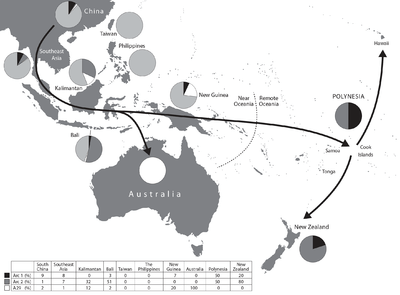

A haplotype is a group of genes in an organism that are inherited together from a single parent.[75][76] Early DNA studies indicated that the dingo was more closely related to the domestic dog than it was to the wolf or the coyote.[77] In 2004, a study compared the DNA sequences of maternal mDNA taken from Australian dingoes. All dingo sequences in the study fell under the mDNA haplotype named A29 or were a single mutation from it.[18] All female dingo sequences since studied exhibit haplotype A29, which falls within the Clade A haplogroup that represents 70% of domestic dogs.[19][78][52][18][79] Haplotype A29 is found in both Australian dingoes and in domestic dogs exclusively in the East Asian region: East Siberia, Arctic America, Japan, Indonesia, New Guinea[18] and in South China, Kalimantan, and Bali.[19] It is associated with the Alaskan Malamute, Alaskan husky, Siberian Husky, and prehistoric dog remains from sites in the Americas.[80] The evidence suggests that the haplotype was introduced from East Asia[18] or southeast Asia[19][20] through the islands of the Malay Archipelago and into Australia.[18][19][20] Haplotype A29 was one of several domestic dog mDNA haplotypes brought into the Malay Archipelago but of these only A29 reached mainland Australia.[18]

In 2020, an mDNA study of ancient dog fossils from the Yellow River and Yangtze River basins of southern China showed that most of the ancient dogs fell within haplogroup A1b, as do the Australian dingoes and the pre-colonial dogs of the Pacific, but in low frequency in China today. The dogs belonging to this haplogroup were once widely distributed in southern China, then dispersed through Southeast Asia into New Guinea and Oceania, but were replaced in China 2,000 YBP by dogs of other lineages. The specimen from the Tianluoshan archaeological site, Zhejiang province dates to 7,000 YBP and possesses one haplotype that is basal to the entire haplogroup A1b lineage.[81]

Sister

In 2011, a study compared the mDNA of the Australian dingo with that of the New Guinea singing dog. The mDNA haplotype A29, or a mutation one step away, was found in all of the Australian dingoes and New Guinea singing dogs studied, indicating a common female ancestry.[19]

In 2012, a study looked at the dingo male lineage using Y chromosome DNA (yDNA) as a genetic marker and found 2 yDNA haplotypes. A haplotype named H3 could be found in domestic dogs in East Asia and Northern Europe. Haplotype H60 had not been previously reported; however, it was one mutation away from haplotype H5 that could be found in East Asian domestic dogs. Only the New Guinea singing dog and dingoes from north-eastern Australia showed haplotype H60, which implies a genetic relationship and that the dingo reached Australia from New Guinea. Haplotype H60 and H3 could be found among the southern Australian dingoes with H3 dominant, but haplotype H3 could only be found in the west of the continent and may represent a separate entry from the northwest.[20]

The existence of a genetic subdivision within the dingo population has been proposed for over two decades but has not been investigated.[18][73] In 2016, a study compared the entire mDNA genome, and 13 loci of the cell nucleus, from dingoes and New Guinea singing dogs. Their mDNA provided evidence that they all carried the same mutation inherited from a single female ancestor in the past, and so form a single clade. Dogs from China, Bali and Kalimantan did not fall within this clade. There are two distinct populations of dingoes in Australia based on both mitochondrial and nuclear evidence. The dingoes found today in the northwestern part of the Australian continent are estimated to have diverged 8,300 YBP followed by a divergence of the New Guinea singing dog 7,800 YBP from the dingoes found today in the southeastern part of the Australian continent. As the New Guinea singing dog is more closely related to the southeastern dingoes, these divergences are thought to have occurred somewhere in Sahul (a landmass which once included Australia, New Guinea and some surrounding islands).[53] The New Guinea singing dog then became a distinct but closely related lineage.[53][82][20] The Fraser Island dingoes are unique because they cluster with the southeastern dingoes but exhibit many alleles (gene expressions) similar to the New Guinea singing dog, in addition to showing signs of admixture with the northwestern dingoes.[53]

These dates suggest that dingoes spread from Papua New Guinea to Australia over the land bridge at least twice. The lack of fossil evidence from northern Australia and Papua New Guinea can be explained by their tropical climate and acidic soil, as there are generally few fossils found in these regions. In 2017, a study of dingoes across a wider area found that the New Guinea singing dog female lineage is more closely related to the southeastern dingoes, and its male lineage is more closely related to dingoes found across the rest of the continent, indicating that the dingo lineage has a complex history.[83]

The dates are well before the human Neolithic Expansion through the Malay Peninsula around 5,500 YBP, and therefore Neolithic humans were not responsible for bringing the dingo to Australia. The Neolithic included gene flow and the expansion of agriculture, chickens, pigs and domestic dogs – none of which reached Australia.[53] There is no evidence of gene flow between Indigenous Australian and early East Asian populations.[53][84] The AMY2B gene produces an enzyme that helps to digest amylase (starch). Similar to the wolf and the husky, the dingo possesses only two copies of this gene,[49] which provides evidence that they arose before the expansion of agriculture.[53][49] Y chromosome DNA indicates that the dingo male lineage is older than Malay Peninsula dogs.[53][82] This provides evidence that the dingo arrived in Australia before the Neolithic expansion.[53]

Cousins

Earlier studies using other genetic markers had found the indigenous Bali dog more closely aligned with the Australian dingo than to European and Asian breeds, which indicates that the Bali dog was genetically diverse with a diverse history,[85][86][87] however only one percent exhibited the maternal A29 mDNA haplotype.[19] In 2011, the mDNA of dogs from the Malay Peninsula found that the two most common dog haplotypes of the Indonesian region, in particular Bali and Kalimantan, was mDNA haplotype A75 (40%) and "the dingo founder haplotype" A29 (8%).[1][19] However, in 2016 a study using the mitochondrial genome that provided much longer mDNA sequences showed that for the A29 haplotype, the dogs from China, Bali and Kalimantan did not fall within the same clade as the dingo and New Guinea singing dog.[83]

In 2013, yDNA was used to compare Australian dingoes, New Guinea singing dogs, and village dogs from Island Southeast Asia. The Bali dogs support the arrival of their ancestors with the Austronesian expansion and the arrival of other domesticates 4,500–3,000 YBP. The data confirms that dingoes carry the unique yDNA haplogroup (H60) and it has been derived from yDNA haplogroup H5. Haplogroup H5 was not found in the village dogs from Island Southeast Asia but it is common in Taiwan. One H5 specimen from Taiwan clustered with one H60 from Australia with the indication of a common ancestor 5,000–4000 YBP and coincides with the expansion of the Daic people of Southern China. The conclusion is that there were two expansions of two types of dogs. Southern China produced the first ancient regional breeds 8,000 years ago, from which they expanded. These were then dominated and replaced by a later explosive expansion of genetically diverse dogs that had been bred in Southeast Asia. If so, the dingo and the New Guinea singing dog, that pre-date the dogs of Island Southeast Asia, would reflect the last vestiges of the earlier ancient breeds.[82]

Wolf admixture

Some dog breeds, including the dingo and the Basenji, are almost as genetically divergent from other dogs as the dog is from the wolf,[48] however this distinctiveness could be reflecting geographic isolation from the admixture that later occurred in other dogs in their regions.[88] Their ancestral lineages diverged from other dogs 8,500 years ago (or 23,000 years ago using another method of timing estimate). Gene flow from the genetically divergent Tibetan wolf forms 2% of the dingo's genome,[48] which likely represents ancient admixture in eastern Eurasia.[49][89]

References

- Greig, K; Walter, R; Matisoo-Smith, L (2016). Marc Oxenham; Hallie Buckley (eds.). The Routledge Handbook of Bioarchaeology in Southeast Asia and the Pacific Islands. Oxford UK: Routledge. pp. 471–475. ISBN 9781138778184.

- Jackson, Stephen and Groves, Colin (2015). Taxonomy of Australian Mammals. CSIRO Publishing, Clayton, Victoria, Australia. pp. 287–290. ISBN 978-1486300129.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Meyer, F.A.A. (1793). Systematisch-summarische Uebersicht der neuesten zoologischen Entdeckungen in Neuholland und Afrika. Dykischen, Leipzig. pp. 1–178. refer pages 33-35. Based on Dingo or Dog of New South Wales, White, p. 280; Dog of New South Wales, Phillip, p. 274. Port Jackson.

- Fleming et al. 2001, pp. 1–16

- Wozencraft, W.C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 575–577. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494. url=https://books.google.com.au/books?id=JgAMbNSt8ikC&pg=PA576

- 1792 Canis antarticus Kerr, Anim. Kingdom, vol. i, p. 136 and pi. opp. Feb. Based on Dog of New South Wales, Gov. Phillip's Voy., p. 274, pi. xlv.

- Jackson, Stephen M.; Groves, Colin P.; Fleming, Peter J.S.; Aplin, KEN P.; Eldridge, Mark D.B.; Gonzalez, Antonio; Helgen, Kristofer M. (2017). "The Wayward Dog: Is the Australian native dog or Dingo a distinct species?". Zootaxa. 4317 (2): 201. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.4317.2.1.

- "Species Canis familiaris Linnaeus, 1758 - Common Dog, Dingo, Domestic Dog". Australian Faunal Directory. Australian Government: Dept of Environment & Energy. 15 December 2017. Retrieved 6 May 2018.

- 1820 Canis familiaris australasiae Desmarest, Tabl. Encyclo. Meth. Mamm., p. 191. Port Jackson, N.S.W. (Peron 6C LeSueur).

- Handbuch der Naturgeschichte. Blumenbach, J.F. 1799. Sechste Auflage. Johann Christian Dieterich, Göttingen. Sixth Edition. [ref page 100, under Canis, under familiaris, under Dingo. Translation: "Dingo. The New Holland dog. Is similar, especially in the head and shoulders, as a fox.]

- 1826 Canis australiae Gray, Narr. Surv. Coasts Austr. (King) ii, p. 412. "1827" — April 18, 1826. New name for australasiae only.

- 1915 Canis dingoides Matschie, Sitz. ges. Nat. Freunde, Berlin, p. 107. p. 107.

- 1915 Canis macdonnellensis Matschie, Sitz. ges. Nat. Freunde, Berlin

- 1831 Canis familiaris novaehollandiae Voigt, Das Thierreich (Cuvier), vol. i, p. 154 (after Easter). New Holland Dingo.

- Kohlbruge J.H.F. Die Tenggeresen. Ein Alter Javanischer Volkstamm. Ethnologische Studie. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1901.

- Troughton. E. (1957). 'Furred Animals of Australia.' (Angus and Robertson: Sydney.)

- Animal remains from Harappa Prashad, B. 1936. Memoirs of the Archaeological Survey of India, no. 51, 1-76 pp., 7 pis. (refer to pages 22-26)

- Savolainen, P.; Leitner, T.; Wilton, A. N.; Matisoo-Smith, E.; Lundeberg, J. (2004). "A detailed picture of the origin of the Australian dingo, obtained from the study of mitochondrial DNA". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 101 (33): 12387–12390. Bibcode:2004PNAS..10112387S. doi:10.1073/pnas.0401814101. PMC 514485. PMID 15299143.

- Oskarsson, M. C. R.; Klutsch, C. F. C.; Boonyaprakob, U.; Wilton, A.; Tanabe, Y.; Savolainen, P. (2011). "Mitochondrial DNA data indicate an introduction through Mainland Southeast Asia for Australian dingoes and Polynesian domestic dogs". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 279 (1730): 967–974. doi:10.1098/rspb.2011.1395. PMC 3259930. PMID 21900326.

- Ardalan, Arman; Oskarsson, Mattias; Natanaelsson, Christian; Wilton, Alan N.; Ahmadian, Afshin; Savolainen, Peter (2012). "Narrow genetic basis for the Australian dingo confirmed through analysis of paternal ancestry". Genetica. 140 (1–3): 65–73. doi:10.1007/s10709-012-9658-5. PMC 3386486. PMID 22618967.

- ICZN (2017). "The Code online (refer Glossary)". International Code of Zoological Nomenclature online. International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature. Archived from the original on 2009-05-24. Retrieved 2018-10-05.

- Harper, Douglas. "canine". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- Linnæus, Carl (1758). Systema naturæ per regna tria naturæ, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I (in Latin) (10 ed.). Holmiæ (Stockholm): Laurentius Salvius. pp. 39–40. Retrieved November 23, 2012.

- Clutton-Brock, Juliet (1995). "2-Origins of the dog". In Serpell, James (ed.). The Domestic Dog: Its Evolution, Behaviour and Interactions with People. Cambridge University Press. pp. 8. ISBN 0521415292.

- "Opinions and Declarations Rendered by the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature - Opinion 91". Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections. 73 (4). 1926.

- Francis Hemming, ed. (1955). "Direction 22". Opinions and Declarations Rendered by the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature. 1C. Order of the International Trust for Zoological Nomenclature. p. 183.

- Francis Hemming, ed. (1957). "Opinion 451". Opinions and Declarations Rendered by the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature. 15. Order of the International Trust for Zoological Nomenclature. pp. 331–333.

- Official Lists and Indexes of Names in Zoology (PDF). International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature. 2014. pp. 126, 225.

- Van Gelder, Richard G. (1978). "A Review of Canid Classification" (PDF). 2646. American Museum of Natural History, Central Park West, 79th Street, New York: 2. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Honaki, J, ed. (1982). Mammal species of the world: A taxonomic and geographic reference (First ed.). Allen Press and the Association of Systematics Collections. p. 245.

- Wayne, R. & Ostrander, Elaine A. (1999). "Origin, genetic diversity, and genome structure of the domestic dog". BioEssays. 21 (3): 247–57. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199903)21:3<247::AID-BIES9>3.0.CO;2-Z. PMID 10333734.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- "Opinion 2027". Opinions and Declarations Rendered by the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature. 60. Order of the International Trust for Zoological Nomenclature. 2003. pp. 81–84.

- Smith 2015, pp. xi–24 Chapter 1 - Bradley Smith

- Crowther, M. S.; M. Fillios; N. Colman; M. Letnic (2014). "An updated description of the Australian dingo (Canis dingo Meyer, 1793)". Journal of Zoology. 293 (3): 192–203. doi:10.1111/jzo.12134.

- Clutton-Brock, Juliet (2015). "Chapter 9. Naming the scale of nature" (PDF). In Alison M Behie; Marc F Oxenham (eds.). Taxonomic Tapestries: The Threads of Evolutionary, Behavioural and Conservation Research. Canberra, Australia: ANU Press. pp. 171–182.

- Oxenham, M.; Behie, A. (2015). "Chapter 18–The warp and weft: Synthesising our taxonomic tapestry" (PDF). In Alison M Behie; Marc F Oxenham (eds.). Taxonomic Tapestries: The Threads of Evolutionary, Behavioural and Conservation Research. ANU Press, The Australian National University, Canberra, Australia. p. 375.

- Koler-Matznick, J.; Yates, B.C.; Bulmer, S.; Brisbin, I.L. Jr. (2007). "The New Guinea singing dog: its status and scientific importance". The Journal of the Australian Mammal Society. 29 (1): 47–56. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.627.5761. doi:10.1071/AM07005.

- Koler-Matznick, Janice; Brisbin, Jr., I. Lehr; Feinstein, Mark (March 2005). "An Ethogram for the New Guinea Singing (Wild) Dog (Canis hallstromi)" (PDF). The New Guinea Singing Dog Conservation Society. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 February 2010. Retrieved 7 April 2010.

- Janice Koler-Matznick (20 January 2004). "The New Guinea Singing Dog" (PDF). KENNEL CLUB BOOK. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 July 2011. Retrieved 30 November 2015.

- Koler-Matznick, Janice; Brisbin Jr, I. Lehr; Feinstein, Mark; Bulmer, Susan (2003). "An updated description of the New Guinea Singing Dog (Canis hallstromi, Troughton 1957)" (PDF). J. Zool. Lond. 261 (2): 109–118. doi:10.1017/S0952836903004060. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-01-13. Retrieved 2015-11-30.

- Benga, Gheorghe; Chapman, Bogdan E; Matei, Horea; Cox, Guy C; Romeo, Tony; Mironescu, Eugen; Kuchel, Philip W (2010). "Comparative NMR studies of diffusional water permeability of red blood cells from different species: XVI Dingo (Canis familiaris dingo) and dog (Canis familiaris)". Cell Biology International. 34 (4): 373–8. doi:10.1042/CBI20090006. PMID 19947930.

- Elledge, Amanda E.; Leung, Luke K.-P.; Allen, LEE R.; Firestone, Karen; Wilton, Alan N. (2006). "Assessing the taxonomic status of dingoes Canis familiaris dingo for conservation". Mammal Review. 36 (2): 142. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2907.2006.00086.x.

- Jones. F. W. (1925). 'The Mammals of South Australia.' Pt. I11 (Government Printer: Adelaide.)

- Wang, Xiaoming; Tedford, Richard H.; Dogs: Their Fossil Relatives and Evolutionary History. New York: Columbia University Press, 2008, page 1

- Nowak, Ronald M. (2018). Walker's Mammals of the World. Monotremes, Marsupials, Afrotherians, Xenarthrans, and Sundatherians. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-1421424675.

- "Australian Dingo". Australian National Kennel Council. ANKC Pty Ltd. 31 August 2009.

- Álvares, F., Bogdanowicz, W., Campbell, L. A. D., Hatlauf, J., Godinho, R., Jhala, Y. V., Werhahn, G. (2019). Old World Canis spp. With taxonomic ambiguity: Workshop conclusions and recommendations. Vairão, Portugal: CIBIO. Canid Biology & Conservation.

- Fan, Zhenxin; Silva, Pedro; Gronau, Ilan; Wang, Shuoguo; Armero, Aitor Serres; Schweizer, Rena M.; Ramirez, Oscar; Pollinger, John; Galaverni, Marco; Ortega Del-Vecchyo, Diego; Du, Lianming; Zhang, Wenping; Zhang, Zhihe; Xing, Jinchuan; Vilà, Carles; Marques-Bonet, Tomas; Godinho, Raquel; Yue, Bisong; Wayne, Robert K. (2016). "Worldwide patterns of genomic variation and admixture in gray wolves". Genome Research. 26 (2): 163–73. doi:10.1101/gr.197517.115. PMC 4728369. PMID 26680994.

- Freedman, Adam H.; Gronau, Ilan; Schweizer, Rena M.; Ortega-Del Vecchyo, Diego; Han, Eunjung; Silva, Pedro M.; Galaverni, Marco; Fan, Zhenxin; Marx, Peter; Lorente-Galdos, Belen; Beale, Holly; Ramirez, Oscar; Hormozdiari, Farhad; Alkan, Can; Vilà, Carles; Squire, Kevin; Geffen, Eli; Kusak, Josip; Boyko, Adam R.; Parker, Heidi G.; Lee, Clarence; Tadigotla, Vasisht; Siepel, Adam; Bustamante, Carlos D.; Harkins, Timothy T.; Nelson, Stanley F.; Ostrander, Elaine A.; Marques-Bonet, Tomas; Wayne, Robert K.; et al. (2014). "Genome Sequencing Highlights the Dynamic Early History of Dogs". PLOS Genetics. 10 (1): e1004016. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004016. PMC 3894170. PMID 24453982.

- Koepfli, K.-P.; Pollinger, J.; Godinho, R.; Robinson, J.; Lea, A.; Hendricks, S.; Schweizer, R. M.; Thalmann, O.; Silva, P.; Fan, Z.; Yurchenko, A. A.; Dobrynin, P.; Makunin, A.; Cahill, J. A.; Shapiro, B.; Álvares, F.; Brito, J. C.; Geffen, E.; Leonard, J. A.; Helgen, K. M.; Johnson, W. E.; O’Brien, S. J.; Van Valkenburgh, B.; Wayne, R. K. (2015-08-17). "Genome-wide Evidence Reveals that African and Eurasian Golden Jackals Are Distinct Species". Current Biology. 25 (16): 2158–65. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2015.06.060. PMID 26234211.

- Jane B. Reece, Noel Meyers, Lisa A. Urry, Michael L. Cain, Steven A. Wasserman, Peter V. Minorsky, Robert B. Jackson, Bernard N. Cooke (2015). "26-Phylogeny and the tree of life". Campbell Biology Australian and New Zealand version (10 ed.). Pierson Australia. pp. 561–562. ISBN 9781486007042.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Thalmann, O.; Shapiro, B.; Cui, P.; Schuenemann, V. J.; Sawyer, S. K.; Greenfield, D. L.; Germonpre, M. B.; Sablin, M. V.; Lopez-Giraldez, F.; Domingo-Roura, X.; Napierala, H.; Uerpmann, H.-P.; Loponte, D. M.; Acosta, A. A.; Giemsch, L.; Schmitz, R. W.; Worthington, B.; Buikstra, J. E.; Druzhkova, A.; Graphodatsky, A. S.; Ovodov, N. D.; Wahlberg, N.; Freedman, A. H.; Schweizer, R. M.; Koepfli, K.- P.; Leonard, J. A.; Meyer, M.; Krause, J.; Paabo, S.; et al. (2013). "Complete Mitochondrial Genomes of Ancient Canids Suggest a European Origin of Domestic Dogs". Science. 342 (6160): 871–4. Bibcode:2013Sci...342..871T. doi:10.1126/science.1243650. hdl:10261/88173. PMID 24233726.

- Cairns, Kylie M.; Wilton, Alan N. (2016). "New insights on the history of canids in Oceania based on mitochondrial and nuclear data". Genetica. 144 (5): 553–565. doi:10.1007/s10709-016-9924-z. PMID 27640201.

- The Voyage of Governor Phillip to Botany Bay Archived 2017-02-13 at the Wayback Machine with an Account of the Establishment of the Colonies of Port Jackson & Norfolk Island. Mazell, P. & Phillip, A. (1789). J: 274–275. Phillip, A. (Ed.). London:Stockdale.

- Iredale, Tom; Troughton, E. Le G., "A Check-List of the Mammals Recorded from Australia". The Australia Museum, Sydney, Memoir VI. Published by Order of the Trustees, Australia, 1934. p90

- Mahoney JA, Richardson BJ (1988) Canidae. "Zoological catalogue of Australia. 5. Mammalia". Ed. D W Walton. Australian Government Publishing Service: Canberra. p218

- Tench, W. (1789). "11" (PDF). A Narrative of the Expedition to Botany Bay. J. Debrett. Note that page numbers are not used in this journal

- Hauser-Schäublin, B.; Krüger, G. "Cook-Forster Collection: Pacific cultural heritage". National Museum Australia. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- Ireland, Tom (1947). "THE SCIENTIFIC NAME OF THE DINGO". Proc. Roy. Zool. Soc. N.S.W. (1946/1947): 34.

- N. De Miklouho-Maclay (1882). "Remark about the Circumvolutions of the Cerebrum of Canis dingo". Proceedings of the Linnean Society of New South Wales. 6 (21–24): 624–626. doi:10.5962/bhl.part.11886.

- Gonzalez, Antonio; Clark, Geoffrey; o'Connor, Sue; Matisoo-Smith, Lisa (2016). "A 3000 Year Old Dog Burial in Timor-Leste". Australian Archaeology. 76: 13–20. doi:10.1080/03122417.2013.11681961. hdl:1885/73337.

- Hoogerwerf, A (1970). Udjung Kulon: The Land of the Last Javan Rhinoceros. E.J. Brill, Leiden. p. 365.

- Jentink, F. A. (1897). "The dog of the Tengger". Notes from the Leyden Museum. 18: 217–220.

- Balme, Jane; o'Connor, Sue; Fallon, Stewart (2018). "New dates on dingo bones from Madura Cave provide oldest firm evidence for arrival of the species in Australia". Scientific Reports. 8 (1): 9933. Bibcode:2018NatSR...8.9933B. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-28324-x. PMC 6053400. PMID 30026564.

- Milham, Paul; Thompson, Peter (2010). "Relative Antiquity of Human Occupation and Extinct Fauna at Madura Cave, Southeastern Western Australia". Mankind. 10 (3): 175–180. doi:10.1111/j.1835-9310.1976.tb01149.x.Original study was published in Mankind v10 p175-180 in 1976.

- Gollan, K (1984) The Australian Dingo:in the shadow of man. In Vertebrate Geozoography and Evolution in Australasia:Animals in Space and Time (Eds M Archer and G Clayton.) p921-927 Hesperian Press, Perth

- Smith 2015, pp. 55–80 Chapter 3 - Bradley Smith & Peter Savolainen

- Ryan, Lyndall (2012). Tasmanian Aborigines. Allen & Unwin, Sydney. pp. 3–6. ISBN 9781742370682.

- Bourke, R. Michael, ed. (2009). Food and Agriculture in New Guinea. Australian National University E. Press. ISBN 9781921536601.

- Monash University. "SahulTime". Retrieved 2015-07-22.

- Wilton, A. N.; Steward, D. J.; Zafiris, K (1999). "Microsatellite variation in the Australian dingo". Journal of Heredity. 90 (1): 108–11. doi:10.1093/jhered/90.1.108. PMID 9987915.

- Greig, Karen; Boocock, James; Prost, Stefan; Horsburgh, K. Ann; Jacomb, Chris; Walter, Richard; Matisoo-Smith, Elizabeth (2015). "Complete Mitochondrial Genomes of New Zealand's First Dogs". PLOS ONE. 10 (10): e0138536. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1038536G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0138536. PMC 4596854. PMID 26444283.

- Corbett, Laurie (1995). The Dingo in Australia & Asia. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-8014-8264-9.

- Corbett, L.K. 2008. Canis lupus ssp. dingo. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2008: e.T41585A10484199. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T41585A10484199.en.

- Cox, C. B.; Moore, Peter D.; Ladle, Richard (2016). Biogeography: An Ecological and Evolutionary Approach. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 106. ISBN 978-1-118-96858-1.

- Editorial Board (2012). Concise Dictionary of Science. New Delhi: V&S Publishers. p. 137. ISBN 978-93-81588-64-2.

- Henderson, Bruce; Coates, Michael; Brimhall, Bernadine; Thompson, Judith (1979). "THE AMINO ACID COMPOSITION OF αT-13 OF GLOBIN FROM a PURE BRED DINGO (CANIS FAMILIARIS DINGO)". Australian Journal of Experimental Biology and Medical Science. 57 (3): 261–3. doi:10.1038/icb.1979.28. PMID 533479.

- Pang, J.-F.; Kluetsch, C.; Zou, X.-J.; Zhang, A.-b.; Luo, L.-Y.; Angleby, H.; Ardalan, A.; Ekstrom, C.; Skollermo, A.; Lundeberg, J.; Matsumura, S.; Leitner, T.; Zhang, Y.-P.; Savolainen, P. (2009). "MtDNA Data Indicate a Single Origin for Dogs South of Yangtze River, Less Than 16,300 Years Ago, from Numerous Wolves". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 26 (12): 2849–64. doi:10.1093/molbev/msp195. PMC 2775109. PMID 19723671.

- Vila, C. (1997). "Multiple and ancient origins of the domestic dog". Science. 276 (5319): 1687–9. doi:10.1126/science.276.5319.1687. PMID 9180076.

- Brown, S K; Darwent, C M; Wictum, E J; Sacks, B N (2015). "Using multiple markers to elucidate the ancient, historical and modern relationships among North American Arctic dog breeds". Heredity. 115 (6): 488–495. doi:10.1038/hdy.2015.49. PMC 4806895. PMID 26103948.

- Zhang, Ming; Sun, Guoping; Ren, Lele; Yuan, Haibing; Dong, Guanghui; Zhang, Lizhao; Liu, Feng; Cao, Peng; Ko, Albert Min-Shan; Yang, Melinda A.; Hu, Songmei; Wang, Guo-Dong; Fu, Qiaomei (2020). "Ancient DNA evidence from China reveals the expansion of Pacific dogs". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 37 (5): 1462–1469. doi:10.1093/molbev/msz311. PMC 7182212. PMID 31913480.

- Sacks, B. N.; Brown, S. K.; Stephens, D.; Pedersen, N. C.; Wu, J.-T.; Berry, O. (2013). "Y Chromosome Analysis of Dingoes and Southeast Asian Village Dogs Suggests a Neolithic Continental Expansion from Southeast Asia Followed by Multiple Austronesian Dispersals". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 30 (5): 1103–18. doi:10.1093/molbev/mst027. PMID 23408799.

- Cairns, Kylie M; Brown, Sarah K; Sacks, Benjamin N; Ballard, J. William O (2017). "Conservation implications for dingoes from the maternal and paternal genome: Multiple populations, dog introgression, and demography". Ecology and Evolution. 7 (22): 9787–9807. doi:10.1002/ece3.3487. PMC 5696388. PMID 29188009.

- Van Holst Pellekaan, Sheila (2013). "Genetic evidence for the colonization of Australia". Quaternary International. 285: 44–56. Bibcode:2013QuInt.285...44V. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2011.04.014.

- Irion, Dawn N; Schaffer, Alison L; Grant, Sherry; Wilton, Alan N; Pedersen, Niels C (2005). "Genetic variation analysis of the Bali street dog using microsatellites". BMC Genetics. 6: 6. doi:10.1186/1471-2156-6-6. PMC 549630. PMID 15701179.

- Runstadler, J. A.; Angles, J. M.; Pedersen, N. C. (2006). "Dog leucocyte antigen class II diversity and relationships among indigenous dogs of the island nations of Indonesia (Bali), Australia and New Guinea". Tissue Antigens. 68 (5): 418–26. doi:10.1111/j.1399-0039.2006.00696.x. PMID 17092255.

- Puja, I. K.; Irion, D. N.; Schaffer, A. L.; Pedersen, N. C. (2005). "The Kintamani Dog: Genetic Profile of an Emerging Breed from Bali, Indonesia". Journal of Heredity. 96 (7): 854–9. doi:10.1093/jhered/esi067. PMID 16014810.

- Freedman, Adam H.; Wayne, Robert K. (2017). "Deciphering the Origin of Dogs: From Fossils to Genomes". Annual Review of Animal Biosciences. 5: 281–307. doi:10.1146/annurev-animal-022114-110937. PMID 27912242.

- Wang, Guo-Dong; Zhai, Weiwei; Yang, He-Chuan; Wang, Lu; Zhong, Li; Liu, Yan-Hu; Fan, Ruo-Xi; Yin, Ting-Ting; Zhu, Chun-Ling; Poyarkov, Andrei D; Irwin, David M; Hytönen, Marjo K; Lohi, Hannes; Wu, Chung-I; Savolainen, Peter; Zhang, Ya-Ping (2015). "Out of southern East Asia: The natural history of domestic dogs across the world". Cell Research. 26 (1): 21–33. doi:10.1038/cr.2015.147. PMC 4816135. PMID 26667385.

Bibliography

- Fleming, P.; Corbett, L.; Harden, R.; Thomson, P. (2001). Managing the impacts of dingoes and other wild dogs. Bureau of Rural Sciences, Canberra. ISBN 978-0642704948.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Smith, Bradley, ed. (2015). The Dingo Debate: Origins, Behaviour and Conservation. CSIRO Publishing, Melbourne, Australia. ISBN 9781486300303.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)