Brandon Lee

Brandon Bruce Lee (February 1, 1965 – March 31, 1993) was an American actor and martial artist, the only son of Bruce Lee. After his father's death during his childhood, Brandon followed him into both fields the older man had excelled in during his brief life. He trained with some of his father's students and studied acting at Emerson College and the Lee Strasberg Theatre and Film Institute. His goal was to act in regular roles as well as martial arts and action movies. Late in the production of his breakthrough film, Alex Proyas's The Crow (1994), based on the comic book of the same name, he was killed in a production accident.

Brandon Lee | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

李國豪 | |||||||||||

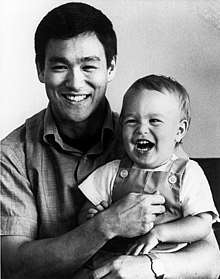

.jpg) Lee in 1992 | |||||||||||

| Born | Brandon Bruce Lee February 1, 1965 Oakland, California, U.S. | ||||||||||

| Died | March 31, 1993 (aged 28) | ||||||||||

| Burial place | Lake View Cemetery, Seattle, Washington, U.S. | ||||||||||

| Nationality | American | ||||||||||

| Occupation | Actor, martial artist, fight choreographer | ||||||||||

| Years active | 1985–1993 | ||||||||||

| Partner(s) | Eliza Hutton (1990–1993) | ||||||||||

| Parents |

| ||||||||||

| Family | Shannon Lee (sister) | ||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 李國豪 | ||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 李国豪 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Signature | |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

Lee followed his early work on stage with movie roles opposite David Carradine in the U.S. and Michael Wong in Hong Kong. For the latter film, Legacy of Rage, his only film in his father's native land, he was nominated for the Hong Kong Film Award for Best New Performer. Later work in Hollywood included Showdown in Little Tokyo with Dolph Lundgren and Rapid Fire, where he also did the fight choreography. Neither film was successfully commercially or critically, although critics noted Lee's onscreen presence.

In 1992, he landed his most notable role as Eric Draven in Alex Proyas's The Crow (1994), based on the comic book of the same name, which would be his final film. On March 31, 1993, only a few days away from completing the film, Lee was accidentally killed after being shot on the set by a prop gun. It was a commercial success and is now considered a cult classic. He is buried alongside his father in Seattle's Lake View Cemetery.

Early life

Brandon was born on February 1, 1965, in Oakland, California, the son of martial artist and actor Bruce Lee and Linda Lee Cadwell (née Emery). The Lees moved to Los Angeles, California, when Brandon was three months old. From a young age, Lee learned martial arts from his father, a major martial arts movie star. While visiting his sets Brandon became intereted in acting.[1] The family lived in Hong Kong from 1971 to 1973, after which his mother moved back to the United States following the death of his father, who became an icon of martial arts and action films built around them.

Lee started studying with [Dan Inosanto]], one of his father's students, when he was 9.[2] Later in his youth, Lee also trained with Richard Bustillo and Jeff Imada.[3][4][5] In his teens, Lee became rebellious. He was asked to leave the Chadwick School for "insubordination"—driving backwards down the school's hill. For a brief time afterwards he attended Bishop Montgomery High School, in Torrance.[6]

Lee received his GED in 1983 at the age of 18, and then went to Emerson College in Boston, Massachusetts, where he majored in theater. That same year, struggling with his identity, he stopped training in martial arts[7] but later resumed it under the guidance of Inosanto and others.[8][9][2][10]

A year later, Lee moved to New York City, where he took acting lessons at the Lee Strasberg Theatre and Film Institute. After his studies, Lee did local theater, joined the Eric Morris American New Theatre, and acted in John Lee Hancock's play Full fed beast.[11][12][7]

Career

1985 to 1990: Early roles

Lee returned to Los Angeles in 1985 and worked as a script reader. During this period, he was approached by casting director Lynn Stalmaster and successfully auditioned for his first credited acting role in Kung Fu: The Movie.[13] It was a feature-length television movie that was a follow-up to the 1970s television series Kung Fu, with David Carradine returning as the lead.[14] In the film, the show's hero, Kwai Chang Caine (Carradine), is forced to fight his hitherto unknown son, Chung Wang (Lee).[15] It aired on ABC on February 1, 1986, Lee's 21st birthday.[16] Lee said that he felt there was some justice in being cast for this role in his first feature, since the TV show's pilot had been conceived for his father.[17]

Lee got his first leading film role later that year in the Hong Kong action crime thriller Legacy of Rage, starring alongside Michael Wong, Regina Kent and Bolo Yeung in a small role. Lee plays Brandon Ma, a young man working two jobs to support his life with his girlfriend May (Kent) and to save up to buy his dream motorcycle. His best friend, Michael Wan (Wong), is an ambitious and murderous drug dealer who eventually blames one of his crimes on him. Ma is sent to jail and vows vengeance on Wan.[18] It was the only film Lee made in Hong Kong, made in Cantonese and directed by Ronny Yu. Lee was nominated for a Hong Kong Film Award for Best New Performer in this role.[19] In May of the following year, it was a critical success at the Cannes Film Festival and commercial success in Japan.[20]

Later that year, Legacy of Rage was released in the Philippines as Dragon Blood,[21] keeping the number one spot in the country for its first five days and becoming a local success.[22][23] Producer Robert Lawrence screened the film and saw Lee's potential to be an action leading man in Hollywood, so the two began working together.[24] After Lee's death, the film was released directly to video in 1998 in the U.S. and Australia the next year.[19] The film has been described as stylistic and fast-paced, with a good performance by Lee.[25] It is considered to be his best genre film.[26][27][28]

In 1987, Lee starred in the unsold television pilot Kung Fu: The Next Generation. It aired on CBS Summer Playhouse, a program that specialized in rejected pilots and allowed the audience to call in to vote for a show to be picked up as a series.[29][30] It was another follow-up to the Kung Fu TV series, moved to the present day, and centered on the story of the grandson and the great-grandson Johnny Caine (Lee) of Kwai Chang Caine.[31] While his father uses his fighting abilities to assist people in need, Johnny Caine chooses a life of crime. After being caught doing a robbery, Johnny is taken into custody by his father who tries to rehabilitate him, but Johnny is tempted to return to crime. The pilot was poorly received and not picked up as a series.[32][33]

In 1988, Lee played a role in "What's In a Name", an episode of the American television series Ohara, starring Pat Morita.[34] That same year the action film Laser Mission was announced.[35] Shot mostly in South Africa, it was his first English-language film. It co-starred Ernest Borgnine who shot his scenes with him in Namibia.[36] The plot concerns a mercenary named Michael Gold (Lee) who is sent to convince Dr. Braun (Borgnine), a laser specialist, to defect to the United States before the KGB acquires him and uses his talents to create a nuclear weapon.[37][38] In the United States the film was released to commercial success on home video in 1990 by Turner Home Entertainment.[39][40] The film is generally panned by critics with a few finding it to be an amusing action B movie.[41][42][43]

In the late 1980s, Lee and his mother had a meeting with Marvel CEO Margaret Loesch through comic book writer Stan Lee. Stan Lee felt that Brandon would be ideal in the role of super-hero Shang-Chi in a film or television adaptation.[44][45]

1991–1993: Hollywood breakthrough

In 1991, he starred opposite Dolph Lundgren in the buddy cop action film Showdown in Little Tokyo. This marked his first studio film and his first American theatrical release. Lee signed a multi-picture deal with 20th Century Fox in 1991. In the film Lee plays Johnny Murata, a Japanese American police officer partnered with a sergeant named Kenner (Lundgren), on patrol in the Los Angeles neighborhood of Little Tokyo. They are sent to infiltrate a new Japanese drug gang, the Iron Claw.[46][47] The movie faced largely negative reviews;[48][49][50] some critics have retrospectively found it entertaining for its genre.[51][52][53]

Lee was among the cameos in the Swedish genre film Sex, Lögner och Videovåld (2002), filmed between 1990 and 1993.[54] The film was completed in 2000.[55] During this time Lee was asked to play his father in the biopic Dragon: The Bruce Lee Story. He turned the role down, finding it awkward to play his father, and too strange to approach the romance between his parents.[12]

In 1992, he had his first starring role in the action thriller Rapid Fire, directed by Dwight H. Little and co-starring Powers Boothe and Nick Mancuso. Lee plays a student who witnesses a murder and is put in a witness protection programme. Lee was reportedly in talks with 20th Century Fox about making two sequels. Many of the fight scenes, choreographed by Lee, contain elements of his father's Jeet Kune Do fighting style.[56] Most critics did not like the film, but many of them found Lee charismatic.[57][58][59] A minority of critics found Rapid Fire to be slick, well acted, and a serviceable action film.[60][61][62] Later that year, Lee landed the lead role in Alex Proyas' film adaptation of the underground comic book The Crow. It tells the story of Eric Draven (Lee), a rock musician raised from the dead by a supernatural crow to avenge his own death as well as the rape and murder of his fiancée by a dangerous gang in his city.[63]

1994: Posthumous success

In 1994, after Lee's death, The Crow opened at number one in the United States in 1,573 theaters grossing $11.7 million, averaging $7,485 per theater.[64] The film ultimately grossed $50.7 million, above its $23 million budget, 24th among all films released in the U.S. that year and 10th among R-rated films released that year. It was the most successful film of Lee's career, and is considered a cult classic.[65][66][67] The film was also a success overseas.[68][69][70][71]

The Crow has an approval rating of 82 percent on Rotten Tomatoes based on 55 reviews; critical consensus there is: "Filled with style and dark, lurid energy, The Crow is an action-packed visual feast that also has a soul in the performance of the late Brandon Lee."[72] The Crow has a score of 71 out of 100 on Metacritic based on 14 critics, indicating "Generally favorable reviews".[73] Reviewers praised the action and visual style.[74][75] Rolling Stone called it a "dazzling fever dream of a movie"; Caryn James, writing for The New York Times, called it "a genre film of a high order, stylish and smooth"; Roger Ebert called it "a stunning work of visual style".[75][76][77] The Los Angeles Times also praised the film.[78][79] Lee's death was alleged to have a melancholic effect on viewers; Desson Howe of The Washington Post wrote that Lee "haunts every frame" and James Berardinelli called the film "a case of 'art imitating death', and that specter will always hang over The Crow".[74][75][80] Berardinelli called it an appropriate epitaph to Lee, Howe called it an appropriate sendoff, and Ebert stated that not only was this Lee's best film, but it was better than any of his father's.[74][75][80]

The film is dedicated to Brandon and his fiancée Eliza Hutton. Lee's mother and Hutton asked for the film to be complete, at the time director Alex Proyas was ready to abandon the project, as a testament to Lee's talent. It hasretained a loyal following many years after its release.[81] Due to the macabre nature of the film and Lee's fate it is often described as a goth cult film.[82]

Some observers found that Lee never quite left the shadow of his father and that The Crow did not live up to Lee's full unexploited potential.[83] Most critics agree that The Crow is a very good film and successful but an eerie conclusion to Lee's career, since he wanted to escape the action genre and move on to dramatic roles.[84]

Death

On March 31, 1993, Lee was filming a scene in The Crow where his character is shot and killed by thugs.[85] In the scene, Lee's character walks into his apartment and discovers his fiancée being beaten and raped. Actor Michael Massee's character fires a Smith & Wesson Model 629 .44 Magnum revolver at Lee as he walks into the room.[86] A previous scene using the same gun had called for inert dummy cartridges (with no powder or primer) to be loaded in the revolver for a close-up scene: dummy cartridges provide the realistic appearance of actual rounds for film scenes that do not require the gun to be fired and use a revolver where the bullets are visible from the front.

Instead of purchasing commercial dummy cartridges, the film's prop crew created their own by pulling the bullets from live rounds, dumping the powder charge and then reinserting the bullets. However, they left the live primer in place at the rear of the cartridge. At some point during filming, the revolver was apparently discharged with one of these improperly deactivated cartridges in the chamber, setting off the primer with enough force to drive the bullet partway into the barrel, where it became stuck (a condition known as a squib load). The prop crew either failed to notice this or failed to recognize the significance of this issue.

In the fatal scene, which called for the revolver to be fired at Lee from a distance of 3.6–4.5 metres (12–15 ft), the dummy cartridges were exchanged with blank rounds, which feature a live powder charge and primer, but no bullet, thus allowing the gun to be fired without the risk of an actual projectile. Since the bullet from the dummy round was already trapped in the barrel, this caused the bullet to be fired from the barrel with almost the same force as if the round were live, and it struck Lee in the abdomen.[87][88]

Lee was rushed to the New Hanover Regional Medical Center in Wilmington, North Carolina. After six hours of surgery, he died at the age of 28. The shooting was ruled an accident due to [[negligence.[89] Lee's death led to the re-emergence of conspiracy theories surrounding his father's similarly early death. Lee's body was flown to nearby Jacksonville, where an autopsy was performed. He was then flown to Seattle, Washington, and buried next to his father at the Lake View Cemetery in a plot that Linda Lee Cadwell had originally reserved for herself.[90][91] A private funeral attended by 40 took place in Seattle on April 3. The following day, 200 of Lee's family, friends, and business associates attended a memorial service at actress Polly Bergen's house in Los Angeles. Among the attendees were Kiefer Sutherland, Lou Diamond Phillips, David Hasselhoff, Steven Seagal, David Carradine, and Melissa Etheridge.[92][93][94][95][5]

Lee's gravestone, designed by local sculptor Kirk McLean, is a tribute to Lee and Hutton. It is composed of two twisting rectangles of charcoal granite which join at the bottom and pull apart near the top. "It represents Eliza and Brandon, the two of them, and how the tragedy of his death separated their mortal life together", said his mother, who described her son, like his father before him, as a poetic, romantic person.[96]

In an interview just prior to his death, Lee quoted a passage from Paul Bowles' book The Sheltering Sky[97] which he had chosen for his wedding invitations; it is now inscribed on his tombstone: Because we don't know when we will die, we get to think of life as an inexhaustible well. And yet everything happens only a certain number of times, and a very small number really. How many more times will you remember a certain afternoon of your childhood, an afternoon that is so deeply a part of your being that you can't even conceive of your life without it? Perhaps four, or five times more? Perhaps not even that. How many more times will you watch the full moon rise? Perhaps twenty. And yet it all seems limitless...[98]

Legacy

At the time of his death, the biopic Dragon: The Bruce Lee Story was ready for release. It was released two months later, with a dedication to his memory in the end credits.[99] Lee's mother and sister attended the premiere. His mother found the film to be excellent and a great tribute for her whole family.[100]

Lee's on-set death paved the way for resurrecting actors to complete or have new performances, since pioneering CGI techniques were used to complete The Crow.[101]

Martial arts and philosophy

Lee was trained from a young age by his father in Jeet Kune Do.[102] Martial artist Bob Wall, who had costarred with Lee in Enter the Dragon, observed that Lee hit with power and had good footwork.[103] Following the death of his father, Lee was trained by Dan Inosanto, a friend and disciple of Bruce Lee.[3][4] Lee said: "It's always been a part of the daily routine. After my father passed away I began working out with the man who was his senior student." According to Jeff Imada who at the time was helping with children's classes at Inosanto's Kali Institute, the fact that he was the son of one of its founders was kept quiet; Lee had difficulty focusing due to seeing his father's photos taking so much space in his studio. Imada said Lee stopped training in his mid-teens to play soccer.[7] Richard Bustillo also trained Lee during his teens and said that Lee worked hard and was always respectful.[5] Lee said that with his training Arnis with Inosanto he specialized in both Kali and Escrima and lasted three to four years.[104]

In 1986, Lee said that he was training in Yee Chuan Tao, a relaxation-based martial art, with a trainer named Mike Vendrell. Lee said that it consisted of exercises such as slow sparring, Chi sao practice; they also worked on a wooden dummy, as well as Vendrell swinging a staff at him while he would duck or jump over. He said later that the exercise helped him be less tense.[10]

Lee eventually returned to the craft with Inosanto as his main trainer and became proud of his heritage.[9] Lee said he did a few amateur fights but did not seek to compete in tournaments. He would bring a camera to Inosanto's studio, both would choreograph fights for Lee's films and would allow him to see how various moves played out on screen. By his mid-twenties Lee was seen practicing regularly at the Inosanto Martial Arts Academy.[11][8] In 1991, Lee was certified by the Thai Boxing Association.[2] While his main goal was dramatic acting, credited the skill to have helped him to boost his career and become an action film leading man.[105]

During the filming of The Crow, Lee said he did cardiovascular exercises to the point of exhaustion using a jumprope, running, riding a LifeCycle, or using a StairMaster, after which he would train at Inosanto's academy where he took Muay Thai classes.[106]

According to Lee's mother, years prior his death Lee became consumed with his father's written philosophy, taking lengthy notes.[2] When asked which martial arts he practiced, he responded:[102]

When people ask me that question, I usually say that my father created the art of Jeet Kune Do and I have been trained in that. However, that's a little too simple to say because Jeet Kune Do was my father's very personal expression of the martial arts. So I always feel a little bit silly saying I practice Jeet Kune Do, although I certainly have been trained in it. It would be more accurate to say that I practice my own interpretation of Jeet Kune Do, just as everyone who practices Jeet Kune Do does.

In August 1992, Bruce Lee biographer John Little asked Brandon Lee what his philosophy in life was, and he replied, "Eat—or die!"[107] Brandon later spoke of the martial arts and self-knowledge:

Well, I would say this: when you move down the road towards mastery of the martial arts—and you know, you are constantly moving down that road—you end up coming up against these barriers inside yourself that will attempt to stop you from continuing to pursue the mastery of the martial arts. And these barriers are such things as when you come up against your own limitations, when you come up against the limitations of your will, your ability, your natural ability, your courage, how you deal with success—and failure as well, for that matter. And as you overcome each one of these barriers, you end up learning something about yourself. And sometimes, the things you learn about yourself can, to the individual, seem to convey a certain spiritual sense along with them.

...It's funny, every time you come up against a true barrier to your progress, you are a child again. And it's a very interesting experience to be reduced, once again, to the level of knowing nothing about what you're doing. I think there's a lot of room for learning and growth when that happens—if you face it head-on and don't choose to say, "Ah, screw that! I'm going to do something else!"

We reduce ourselves at a certain point in our lives to kind of solely pursuing things that we already know how to do. You know, because you don't want to have that experience of not knowing what you're doing and being an amateur again. And I think that's rather unfortunate. It's so much more interesting and usually illuminating to put yourself in a situation where you don't know what's going to happen, than to do something again that you already know essentially what the outcome will be within three or four points either way.[108]

Personal life

Lee is the grandson of Lee Hoi-chuen, the nephew of Robert Lee Jun-fai, and the brother of Shannon Lee.[109][110] Lee's paternal great grandfather was Ho Kom Tong, a Chinese philanthropist of Dutch-Jewish descent who was son of Charles Henry Maurice Bosman (1839–1892).[111][112] Lee's mother Linda Emery has Swedish and German roots. According to the book, Lee “proudly told everyone” about his newborn son Brandon’s diverse features, describing him as perhaps the only Chinese person with blond hair and grey eyes.[113]

Actor and martial artist Chuck Norris, a friend and collaborator of Lee's father, said that when Bruce died, he kept in touch with Lee's family, and that his son Eric Norris and Brandon were friends at a young age.[114][115]

Lee was a friend of Chad Stahelski, his double after his death during The Crow. The two had trained together at the Inosanto Martial Arts Academy.[8]

In 1990, Lee met Eliza Hutton at director Renny Harlin's office, where she was working as his personal assistant. Lee and Hutton moved in together in early 1991 and became engaged in October 1992.[116] They planned to get married in Ensenada, Mexico on April 17, 1993, a week after Lee was to complete filming on The Crow.[92][93][94][95]

Filmography

| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1986 | Legacy of Rage | Brandon Mac | Alternative title: Long Zai Jiang Hu, Dragon Blood |

| 1989 | Laser Mission | Michael Gold | Alternative titles: Mercenary Man, Soldier of Fortune |

| 1991 | Showdown in Little Tokyo | Johnny Murata | |

| 1992 | Rapid Fire | Jake Lo | |

| 1994 | The Crow | Eric Draven/The Crow | Shot and killed as a result of negligence during filming. Special effects and a stand-in were used to complete Lee's remaining scenes. Released posthumously. |

| 2002 | Sex, Lögner och Videovåld | Bystander | Cameo in low budget Swedish film. Released posthumously. |

| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1986 | Kung Fu: The Movie | Chung Wang | Television Film |

| 1987 | Kung Fu: The Next Generation | Johnny Caine | Television Pilot. Aired on CBS Summer Playhouse |

| 1988 | Ohara | Kenji | Episode: What's in a Name |

Awards and nominations

| Year | Awards | Category | Nominated work | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1986 | Hong Kong Film Awards | Best New Performer | Legacy of Rage | Nominated |

| 1994 | Fangoria Chainsaw Awards | Best Actor | The Crow | Won |

| MTV Movie & TV Awards | Best Male Performance | Nominated | ||

References

- "Brandon Lee follows in his dad's shoes, but he hopes to win respect as an actor in his own right". Deseret News. 1992-07-24. Retrieved 2019-04-22.

- "Family Matters". The Age. May 30, 1993.

- Reid, Dr. Craig D. (1999). "Shannon Lee: Emerging From the Shadow of Bruce Lee". Black Belt Magazine. Active Interest Media. 37 (10): 33 – via Google Books.

- Jeffrey, Douglas (1993). "The Tragic death of Brandon Lee". Black Belt. 31 (7): 29–30.

- Jeffrey, Douglas (1993). "The Tragic death of Brandon Lee". Black Belt Magazine. Vol. 31 no. 7. p. 29.

- "Explore 1980 Bishop Montgomery High School Yearbook, Torrance CA". classmates.com.

- Baiss, Bridget (2012-02-07). The Crow: The Story Behind the Film. Titan Books (US, CA). ISBN 978-1-78116-184-5.

- Mary Anne Butler (2019-05-16). "Chad Stahelski Talks Losing Brandon Lee, 'The Crow' at 25". Bleeding Cool News And Rumors. Retrieved 2019-12-27.

- Buck, Jerry (April 25, 1991). "Son of Lee sees more to life than 'Kung Fu'". Logansport Pharos-Tribune.

- Coleman, Jim (1994). "Brandon Lee's first interview!". Black Belt Magazine. Vol. 32 no. 9. pp. 47–48.

- Jeffrey, Douglas (1993). "The Tragic death of Brandon Lee". Black Belt magazine. 31 (7): 29–30.

- Koehler, Sezin (July 23, 2019). "The untold truth of Brandon Lee". Looper.com. Retrieved 2019-12-28.

- Michael A. Lipton (September 7, 1992). "Son of Bruce Breaks Loose". People. Retrieved 2019-04-23.

- Crockett, Lana (1986-01-30). "Carradine re-creates Kung Fu". Green Bay Press-Gazette: 21 – via Newspapers.

- "Kung Fu: The Movie (1986) – Richard Lang | Synopsis, Characteristics, Moods, Themes and Related". AllMovie. Retrieved 2019-06-17.

- "Enter the Son of the Dragon: Bruce Lee's Only Boy, Brandon, Gets No Kick from Kung Fu". People. February 3, 1986. Retrieved 2018-10-07.

- News, Deseret (1992-07-24). "BRANDON LEE FOLLOWS IN HIS DAD'S SHOES, BUT HE HOPES TO WIN RESPECT AS AN ACTOR IN HIS OWN RIGHT". Deseret News. Retrieved 2019-12-26.

- Legacy of Rage (VHS). TAI SENG VIDEO MARKETING (ENT.). 1998. 601643563831.

- "Legacy Of Rage | TV Guide". TV Guide. Retrieved 2019-04-23.

- "Bruce Lee Jr. talks about his father". Manila Standard: 15. 15 July 1987 – via Google news.

- "Grand Opening Today". Manila Standard. Standard Publishing, Inc. 16 July 1987. p. 15. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

The Most Awaited Movie of the Decade!

- "5th 'Bruce Lee Mania' Day! We are real No. 1". Manila Standard: 14. 19 July 1987 – via Google news.

- "6th 'Bruce Lee Mania' Day!". Manila Standard: 15. 21 July 1987 – via Google news.

- Koltnow, Barry (26 August 1992). "A karate chop off the old block". The Record: 46 – via Newspapers.

- Myers, Randy (22 May 1998). "Reviews". News Press: 94 – via Newspapers.

- "Mondo Video". Daily News: 81. 8 May 1998 – via Newspapers.

- Harris, Paul (22 March 1999). "Today's Films". The Age: 19 – via Newspapers.

- Lowing, Rob (21 March 1999). "Movies". The Sydney Morning Herald: 243 – via Newspapers.

- "Kung Fu: The Next Generation (1987) - Overview". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved 2018-10-07.

- Kelley, Bill (1987-06-19). "'Kung Fu' a one-shot sequel to series". South Florida Sun Sentinel: 56 – via Newspapers.

- Coleman, Jim (April 1, 1986). "Bruce Lee's Son Speaks Out". Black Belt. 24 (4): 20–24, 104.

- Zuckerman, Faye (1987-06-19). "On TV tonight". El Paso Times: 36 – via Newspapers.

- Bianculli, David (1987-06-19). "TV tonight". The Philadelphia Inquirer. 316: 42 – via Newspapers.

- "Ohara | TV Guide". TV Guide. Retrieved 2019-12-24.

- Scott, Vernon (16 October 1988). "Star of five new films, Borgnine says there's nothing like work". Ottawa Citizen: 38 – via Newspapers.

- "Borgnine to play scientist". The Courier-Journal: 109. 29 January 1989 – via Newspapers.

- Noble, Barnes &. "Laser Mission". Barnes & Noble. Retrieved 2018-10-07.

- Davis, Beau (1990). Laser Mission (VHS). Direct Source Special Products. 79836 40653 8.

- Hartl, John (17 August 1990). "Chong's 'Far Out, Man!' is en route to rental stores". York Daily Record. 229: 55 – via Newspapers.

- Tribune, Max J. Alvarez Special to the. "BIG NAMES LOOK FOR BRIGHT LIGHTS IN VIDEOLAND". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 2019-04-23.

- Casimir, Jon (1 August 1994). "Sly gets the joke in action spoof". The Sydney Morning Herald. 48,957: 51 – via Newspaper.

- "Bad Movie Diaries: Laser Mission (1989)". Paste. 2019-06-18. Retrieved 2019-07-20.

- "Schlock Value: Laser Mission (1989)". Talk Film Society. Retrieved 2019-07-20.

- Francisco, Eric. "Stan Lee Tried to Make a Shang-Chi Movie Starring Bruce Lee's Son". Inverse. Retrieved 2019-04-23.

- Mallory, Michael (2012-06-21). "Margaret Loesch Fights for Marvel". Animation Magazine. Retrieved 2019-12-27.

- Goh, Robbie B. H.; Wong, Shawn (2004). Asian diasporas: cultures, identities, representations. Hong Kong University Press. p. 46. ISBN 978-962-209-673-8. Retrieved 21 May 2011.

- Willis, John (February 2000). Screen World 1992. Applause. ISBN 978-1-55783-135-4. Retrieved 21 May 2011.

- Thomas, Kevin (1991-08-26). "MOVIE REVIEW : 'Showdown in Little Tokyo' a Class Martial-Arts Act". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2010-12-04.

- "Showdown in Little Tokyo". Variety. 1990-12-31. Archived from the original on November 7, 2012. Retrieved 2010-12-04.

- Canby, Vincent (1991-09-22). "Review/Film; 'Showdown In Little Tokyo'". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-12-14.

- "The Best Movie You Never Saw: Showdown in Little Tokyo". joblo.com. 2018-12-07. Retrieved 2019-09-01.

- "Film Review: Showdown in Little Tokyo (1991)". HNN | Horrornews.net. 2018-11-23. Retrieved 2019-09-01.

- "Showdown in Little Tokyo Blu-ray Review: The Ultimate Guilty Pleasure of the 90s – Cinema Sentries". cinemasentries.com. Retrieved 2019-09-01.

- Crick, Robert Alan (2015-06-14). "Appendix". The Big Screen Comedies of Mel Brooks. McFarland. p. 233. ISBN 978-1-4766-1228-7.

- Stevenson, Jack (2015-09-02). "The Players". Scandinavian Blue: The Erotic Cinema of Sweden and Denmark in the 1960s and 1970s. McFarland. p. 263. ISBN 978-1-4766-1259-1.

- Star-Telegram, Fort Worth. "Brandon Lee follows father's footsteps". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved 2019-04-22.

- Siskel, Gene (1992-08-21). "Dump 'Rapid Fire,' But Keep Brandon Lee". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 2010-09-20.

- Holden, Stephen (1992-08-21). "Review/Film; Violence Compounded by More Violence". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-12-14.

- "Rapid Fire (1992)". Retrieved 2017-10-02.

- McBride, Joseph; McBride, Joseph (1992-08-14). "Rapid Fire". Variety. Retrieved 2019-10-27.

- Travis, Ed (2018-09-04). "RAPID FIRE: Brandon Lee's Star Is Born". Medium. Retrieved 2019-10-27.

- "MOVIE REVIEW : 'Rapid Fire' Launches Heir to Lee's Kung Fu Legacy". Los Angeles Times. 1992-08-21. Retrieved 2019-10-27.

- The Crow (film) (in English, French, and Spanish). Miramax / Dimension Home Entertainment. ISBN 0-7888-2602-6. 21460.

- Fox, David J. (16 May 1994). "'The Crow' Takes Off at Box Office". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- "The Crow (1994)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved March 12, 2011.

- Hammer, Eleanor Goodman2019-01-04T12:00:00Z Metal. "The Crow: the macabre tale of the ultimate cult goth movie". Metal Hammer Magazine. Retrieved 2019-04-22.

- Fox, David J. (May 16, 1994), "'The Crow' Takes Off at Box Office", Los Angeles Times, Tribune Company, retrieved March 12, 2011

- "The Crow". 25th Frame. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- "The Crow (1994)". JP's Box-Office. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- "Ворон — дата выхода в России и других странах". KinoPoisk (in Russian). Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- "영화정보". KOFIC. Korean Film Council. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

- "The Crow". Rotten Tomatoes. 1 January 1994. Retrieved December 30, 2019.

- "The Crow". Metacritic. Retrieved November 6, 2015.

- Howe, Desson (May 13, 1994), "'The Crow' (R)", The Washington Post, The Washington Post Company, retrieved March 12, 2011

- Ebert, Roger (May 13, 1994), "The Crow", Chicago Sun-Times, Sun-Times Media Group, retrieved March 12, 2011

- Travers, Peter (May 11, 1994), "The Crow", Rolling Stone, Wenner Media, retrieved March 12, 2011

- James, Caryn (May 11, 1994), "Eerie Links Between Living and Dead", The New York Times, The New York Times Company, retrieved March 12, 2011

- Rainer, Peter (May 11, 1994), "Movie Review: 'The Crow' Flies With Grim Glee", Los Angeles Times, Tribune Company, retrieved March 12, 2011

- Welkos, Robert W. (May 11, 1994), "Movie Review: Life After Death: A Hit in the Offing?", Los Angeles Times, Tribune Company, retrieved March 12, 2011

- Berardinelli, James (1994), "Review: the Crow", ReelViews, retrieved March 12, 2011

- Goodman2019-01-04T12:00:00Z, Eleanor. "The Crow: the macabre tale of the ultimate cult goth movie". Metal Hammer Magazine. Retrieved 2019-12-29.

- "How 'The Crow' transcended the tragic, on-camera death of its star to become a superhero classic". The Independent. 2019-05-21. Retrieved 2019-12-28.

- Seigel, Jessica (14 April 1993). "Brandon Lee never escaped shadow of his famous dad". Detroit Free Press.

- McKee, Amber (19 May 1993). "The Crow: an apt eulogy for Brandon Lee". The Park Record.

- Richard Harrington (15 May 1994). "The Shadow of the Crow". The Washington Post.

- Welkos, Robert W. (April 1, 1993). "Bruce Lee's Son, Brandon, Killed in Movie Accident". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2010-12-07.

- Pristin, Terry (August 11, 1993). "Brandon Lee's Mother Claims Negligence Caused His Death". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2010-12-04.

Movies: Linda Lee Cadwell sues 14 entities regarding the actor's 'agonizing pain, suffering and untimely death' last March on the North Carolina set of "The Crow"

- Harris, Mark (April 16, 1993). "The Brief Life and Unnecessary Death of Brandon Lee". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 2010-12-07.

- "Negligence is Seen in Actor's Death". The New York Times. 29 April 1993. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- Ramble

- Lakeview Cemetery website. Search for Lee. Only use last name.

- "Shooting of a star (part 1)". The Observer. May 3, 1993.

- "Shooting of a star (part 2)". The Observer. May 3, 1993.

- "Shooting of a star (part 3)". The Observer. May 3, 1993.

- "Shooting of a star (part 4)". The Observer. May 3, 1993.

- "New Gravestone Marks Brandon Lee's Final Rest", By M.L. LYKE Seattle P-I Reporter – June 1, 1995.

- "Brandon Lee's last interview". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 2019-11-27.

- Lyke, M.L. (June 4, 1995). "Visitors leave objects of devotion on graves of Bruce Lee and son". The Santa Fe New Mexican.

- Higgins, Bill (April 30, 1993). "A Film Premiere Tempered by Loss : Memories: Brandon Lee's death made the opening of Bruce Lee's bio a poignant event. But the elder Lee's widow said it was a tribute to both". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2010-12-03.

- "A Film Premiere Tempered by Loss : Memories: Brandon Lee's death made the opening of Bruce Lee's bio a poignant event. But the elder Lee's widow said it was a tribute to both". Los Angeles Times. 1993-04-30. Retrieved 2019-12-28.

- "14 Actors Resurrected With Crazy CGI (And 6 That Can Never Be)". ScreenRant. 2018-08-09. Retrieved 2019-12-27.

- Little, John (1993). "Brandon Lee's final martial arts interview". Black Belt Magazine. Vol. 31 no. 8. pp. 24–25–26–27–28–121–122–123.

-

- Jeffrey, Douglas (1993). "The Tragic death of Brandon Lee". Black Belt Magazine. Vol. 31 no. 7. p. 96.

- Coleman, Jim (1994). "Brandon Lee's first interview!". Black Belt Magazine. Vol. 32 no. 9. p. 47.

- News, Deseret (1992-07-24). "BRANDON LEE FOLLOWS IN HIS DAD'S SHOES, BUT HE HOPES TO WIN RESPECT AS AN ACTOR IN HIS OWN RIGHT". Deseret News. Retrieved 2019-12-28.

- Little, John (1993). "Brandon Lee's final martial arts interview". Black Belt Magazine. Vol. 31 no. 8. p. 28.

- Little, John (1996). The Warrior Within – The philosophies of Bruce Lee to better understand the world around you and achieve a rewarding life. Contemporary Books. p. 129. ISBN 0-8092-3194-8.

- Little, John (1996). The Warrior Within – The philosophies of Bruce Lee to better understand the world around you and achieve a rewarding life. Contemporary Books. p. 150. ISBN 0-8092-3194-8.

- Chow, Vivienne (2012-07-20). "Bruce Lee's legacy leaves a family divided". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 2019-12-30.

- Wolfe, April (2016-09-06). "How Bruce Lee's Daughter Is Sharing His Philosophies With the Digital Generation". LA Weekly. Retrieved 2019-12-30.

- "Brandon Lee 李國豪". geni_family_tree. Retrieved 2020-02-16.

- Russo, Charles (2016-05-19). "Was Bruce Lee of English Descent?". Vice. Retrieved 2020-02-16.

- Blank, Ed (August 9, 2018). "Mixed Martial Artist: Uncovering Bruce Lee's Hidden Jewish Ancestry". Jewish Federation of San Diego County. Retrieved 2020-03-30.

- Blank, Ed (April 3, 1983). "King Of The Good Guys". The Pittsburgh Press. 99: 85 – via Newspapers.

- Murray, Steve (May 3, 1993). "Actor's new kick: family values". The Atlanta Constitution: 25 – via Newspapers.

- Baiss, Bridget (2012-02-07). The Crow: The Story Behind the Film. Titan Books (US, CA). ISBN 978-1-78116-184-5.

Work cited

- Jeffrey, Douglas (1993). "The Tragic death of Brandon Lee". Black Belt Magazine. Vol. 31 no. 7. pp. 24–25–26–27–28–29–96–97.

- Little, John (1993). "Brandon Lee's final martial arts interview". Black Belt Magazine. Vol. 31 no. 8. pp. 24–25–26–27–28–121–122–123.

- Coleman, Jim (1994). "Brandon Lee's first interview!". Black Belt Magazine. Vol. 32 no. 9. pp. 44–45–46–47–48–49.

- Little, John (1996). The Warrior Within – The philosophies of Bruce Lee to better understand the world around you and achieve a rewarding life. Contemporary Books. p. 150. ISBN 0-8092-3194-8.

- Baiss, Bridget. The Crow: The Story Behind The Film. London: Making of The Crow Inc, 2000. ISBN 1-870048-54-7

Further reading

- Allen, Terence (1994). "The movies of Brandon Lee". Black Belt Magazine. Vol. 32 no. 9. pp. 51–52–53–54–55–56.

- Pilato, Herbie J. The Kung Fu Book of Caine: The Complete Guide to TV's First Mystical Eastern Western. Boston: Charles A. Tuttle, 1993. ISBN 0-8048-1826-6.

- Dyson, Cindy. They Died Too Young: Brandon Lee. Philadelphia: Chelsea House, 2001. ISBN 0-7910-5858-1