Bradwell nuclear power station

Bradwell nuclear power station is a partially decommissioned Magnox power station located on the Dengie peninsula at the mouth of the River Blackwater, Essex. As of 2016, China General Nuclear Power Group and China National Nuclear Corporation are considering Bradwell for the site of a new nuclear power station.

| Bradwell nuclear power station | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Country | England |

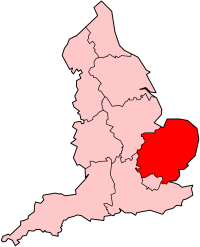

| Location | Bradwell-on-Sea, Essex |

| Coordinates | 51°44′29″N 0°53′49″E |

| Status | Decommissioned |

| Construction began | 1957 |

| Commission date | 1962 |

| Decommission date | 2002 |

| Owner(s) | Nuclear Decommissioning Authority |

| Operator(s) | Magnox Ltd |

| Nuclear power station | |

| Reactor type | Magnox |

| Reactor supplier | The Nuclear Power Group (TNPG) |

| Power generation | |

| Units operational | Parsons |

| Units decommissioned | 2 reactors 242 MW |

| External links | |

| Website | magnoxsouthsites.com |

| Commons | Related media on Commons |

History

Construction of the power station, which was undertaken by a consortium involving Clarke Chapman, Head Wrightson, C. A. Parsons & Co., A. Reyrolle & Co., Strachan & Henshaw and Whessoe and known as the Nuclear Power Plant Company (NPPC),[1] began in December 1957, and electricity generation started in 1962. It had two Magnox reactors with a design output of 300 MW of net electrical output, although this was reduced to 242 MW net electrical in total[2] as a result of the discovery of breakaway oxidation of mild-steel components inside the reactor vessel. Its peak output, achieved in the early 1960s, was nearly 10% above the design value. On a typical day it could supply enough electricity to meet the needs of three towns the size of Chelmsford, Colchester and Southend put together. It is the closest power station to Southend. The reactors were supplied by The Nuclear Power Group (TNPG), and the 9 turbines and 12 gas circulators by C. A. Parsons & Co.[3] (6 of 52 MW main turbines supplying power to the grid, 3 of 22.5 MW auxiliaries turbines, one for each reactor for driving the gas circulators, with one standby auxiliary turbine). Steam pressure and temperature at the turbine stop valves was 730 psi (50.3 bar) and 371 °C.[4]

Electricity output

Electricity output from Bradwell power station over the period 1964-1984 was as follows.[4][5]

Bradwell annual electricity output GWh.

Location

Bradwell was built on the edge of a former World War II airfield, 1.5 miles from the Essex coastline. Its location was deliberately chosen, as the land had minimal agricultural value, offered easy access, was geologically sound and had an unlimited source of cooling water from the North Sea.

Nuclear fuel for Bradwell was delivered and removed via the nearest railhead, a loading facility adjacent to Southminster railway station on the Crouch Valley line. This included a dedicated siding and a gantry crane.[6]

In 1969, a new Honeywell 316 was installed as the primary reactor temperature-monitoring computer; this was in continuous use until summer 2000, when the internal 160k disk failed. Two PDP-11/70s, which had previously been secondary monitors, were moved to primary.

Decommissioning

In 1999, it was announced that the station would cease operation in 2002 – the first UK station to be closed on a planned basis. On 28 March 2002 Lord Braybrooke, Lord Lieutenant of Essex, unveiled a plaque to mark the cessation of electricity generation and the beginning of the decommissioning stage.[7] All spent nuclear fuel was removed from the site by 2005, the turbine hall was demolished in 2011, and by 2016 underground waste storage vaults had been emptied and decontaminated.[8]

Defuelling and removal of most buildings is expected to take until 2027, followed by a care and maintenance phase from 2027 to 2087. Demolition of reactor buildings and final site clearance is planned for 2083 to 2093 [9]

Future plans

In 2007 Bradwell became one of the sites being considered by British Energy for redevelopment in a new round of nuclear reactors.[10] On 18 October 2010, the British government announced that Bradwell was one of the eight sites it considered suitable for future nuclear power stations.[11]

In 2014 The Sunday Times reported that the China General Nuclear Power Group and China National Nuclear Corporation were preparing preliminary designs for a 3 GW nuclear power station at Bradwell to submit to the Office for Nuclear Regulation.[12]

On 21 September 2015, Energy Secretary Amber Rudd announced that "China was expected to lead the construction of a Beijing-designed nuclear station at the (Bradwell) Essex site".[13][14] EDF's chief executive Jean-Bernard Lévy stated that the reactor design under consideration is the Hualong One.[15] On 21 October 2015, it was reported that Britain and China have reached Strategic Investment Agreements for three nuclear power plants, including one at Bradwell.[16]

On 19 January 2017, the UK Office for Nuclear Regulation started their Generic Design Assessment process for the Hualong One design, expected to be completed in 2021, in advance of possible deployment at Bradwell.[17] The target commercial operation date is about 2030.[18]

There are concerns[19] about Chinese government involvement in the project[20]. State-owned China General Nuclear Power Group[21], specified as a designer and operator of the plant, is blacklisted by the United States Department of Commerce for attempting to acquire advanced U.S. nuclear technology and material for diversion to military use.[22][23]

Safety record

In 1966, twenty natural uranium fuel rods were stolen from Bradwell.[24] The rods were stolen for their scrap value by Harold Arthur Sneath, a worker at the plant. The theft was discovered by the local police when a van driven by Dennis Patrick Hadley, who was transporting the rods to their final destination, was stopped due to its defective steering. The rods were recovered and, in the subsequent court case, Sneath and Hadley were bound over for five years, each fined £100, and were required to contribute to the costs of the court case. Neither was said to have understood the consequences of the theft.[25]

On 22 January 2011, a fire broke out during the decommissioning work as titanium condenser tubes were being cut up. No radiation was released from this fire.[26]

In literature

The construction of the original power station is the subject of the Michael Morpurgo story Homecoming.[27]

See also

References

- The UK Magnox and AGR Power Station Projects.

- "Bradwell – Facts and figures". Magnox Ltd. Archived from the original on 30 March 2009. Retrieved 7 February 2011.

- Nuclear Power Plants in the UK – England Archived 2009-07-19 at the Portuguese Web Archive.

- CEGB Statistical Yearbook (various years). CEGB, London.

- CEGB Annual report and Accounts, 1963

- Brailsford, Martyn (2016). Railway Track Diagrams Book 2: Eastern. Frome: Trackmaps. pp. 10A. ISBN 9780954986681.

- "Nuclear Power Plant Closes". BBC Online. 28 March 2002.

- "Magnox completes decontamination at Bradwell". World Nuclear News. 30 June 2016. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- "The 2010 UK Radioactive Waste Inventory: Main Report" (PDF). Nuclear Decommissioning Agency/Department of Energy & Climate Change. February 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 March 2012. Retrieved 22 May 2012.

- "British Energy eyes nuclear sites". BBC Online. 27 November 2007.

- "Nuclear power: Eight sites identified for future plants". BBC News. BBC. 18 October 2010. Retrieved 18 October 2010.

- "Chinese nuclear plans for Bradwell power station could be 'catastrophic'". Essex Chronicle. 29 August 2014. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- "UK guarantees 2bn nuclear plant deal as China investment announced". BBC. 21 September 2015. Retrieved 22 September 2015.

- George Parker (21 September 2015). "UK paves path for west's first China-designed nuclear reactor". Financial Times. Retrieved 22 September 2015.

- Geert De Clercq (23 September 2015). "Only China wants to invest in Britain's new £2bn Hinkley Point nuclear plant because no one else thinks it will work, EDF admits". The Independent. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-34587650

- "UK GDA reports good progress for AP1000 and UK ABWR". Nuclear Engineering International. 23 March 2017. Retrieved 28 March 2017.

- "China General Nuclear ready to ramp up UK ambitions". World Nuclear News. 6 December 2018. Retrieved 10 December 2018.

- https://www.ft.com/content/1a44e152-b762-11e8-b3ef-799c8613f4a1

- https://www.ft.com/content/8a1d7432-0e8b-11e9-a3aa-118c761d2745

- https://www.telegraph.co.uk/technology/2019/08/15/questions-raised-chinas-involvement-hinkley-point-us-trade-blacklist

- https://www.scmp.com/business/companies/article/2002539/china-general-nuclear-power-accused-espionage-its-adviser-us

- https://www.pillsburylaw.com/en/news-and-insights/china-industry-entity-list.html

- Amory B. Lovins & L. Hunter Lovins. Brittle Power. Brick House Publishing Company. p. 146. ISBN 0-931790-49-2. Retrieved 10 August 2007.

- "Uranium theft not sinister". Burnham on Crouch and Dengie Hundred Advertiser. Essex record office. February 1967.

- "Bradwell nuclear power station hit by fire". BBC News. 21 January 2011.

- London: Walker Books. ISBN 978-1-4063-3202-5

External links

- Map sources for Bradwell nuclear power station

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bradwell nuclear power station. |

- British Nuclear Group

- UK operator fined £400,000 for 14-year radioactive leak

- The story of Bradwell Power Station

- Bradwell-on-Sea Power Station, Nuclear Engineering International wall chart, April 1957