Blue Division

The Blue Division (Spanish: División Azul, German: Blaue Division), officially designated as División Española de Voluntarios by the Spanish Army and as 250. Infanterie-Division in the German Army, was a unit of Spanish volunteers who served in the German Army on the Eastern Front during the Second World War.[2]

| 250th Infantry Division 250. Infanterie-Division (German) Spanish Volunteer Division División Española de Voluntarios (Spanish) | |

|---|---|

Badge of the Spanish Volunteer Division | |

| Active | 24 June 1941 – 21 March 1944 |

| Country | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Infantry |

| Size | 47,000 troops[1] |

| Nickname(s) | División Azul |

| Motto(s) | "Sin relevo posible, hasta la extinción"[lower-alpha 1] |

| Engagements | World War II |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Agustín Muñoz Grandes Emilio Esteban Infantes |

Blue Division casualties throughout the Soviet-German conflict totaled 22,700 (3,934 battle deaths, 570 disease deaths, 326 missing or captured, 8,466 wounded, 7,800 sick, and 1,600 frostbitten).[1] In action against the Blue Division, the Red Army suffered 49,300 casualties.[1]

Origins

Although Spanish caudillo Francisco Franco was neutral and did not bring Spain into World War II on the side of Nazi Germany, he permitted volunteers to join the German Army (Wehrmacht) on the condition they would only fight against the Soviet Union on the Eastern Front, and not against the Western Allies or any Western European occupied population. In this manner, he could keep Spain at peace with the Western Allies, while repaying German support during the Spanish Civil War and providing an outlet for the strong anti-Communist sentiments of many Spanish nationalists. Spanish foreign minister Ramón Serrano Súñer suggested raising a volunteer corps, and at the commencement of Operation Barbarossa, Franco sent an official offer of help to Berlin.[3]

Hitler approved the use of Spanish volunteers on 24 June 1941. Volunteers enlisted at recruiting offices in all the metropolitan areas of Spain. Cadets from the officer training school in Zaragoza volunteered in particularly large numbers and were given leave by the Spanish army. Initially, the Spanish government was prepared to send about 4,000 men, but soon realized that there were more than enough volunteers to fill an entire division: 18,104 men in all, with 2,612 officers and 15,492 soldiers.

Fifty per cent of officers and NCOs were professional soldiers given leave from the Spanish army, including many veterans of the Spanish Civil War. Many others were members of the Falange, Spain's sole party. General Agustín Muñoz Grandes was assigned to lead the volunteers. Because the soldiers could not use official Spanish army uniforms, they adopted a symbolic uniform comprising the red berets of the Carlists, the khaki trousers of the Spanish Legion, and the blue shirts of the Falangists—hence the nickname "Blue Division". This uniform was used only while on leave in Spain; in the field, soldiers wore the German Army field grey uniform with a shield on the upper right sleeve bearing the word "España" and the Spanish national colours.

Operational history

Organization and training

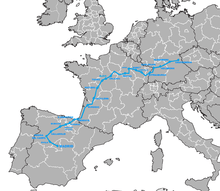

On July 13, 1941, the first train left Madrid for Grafenwöhr, Bavaria for a further five weeks of training. There they became the German Army's 250th Infantry Division and were initially divided into four infantry regiments, as in a standard Spanish division. To aid their integration into the German supply system, they soon adopted the standard German model of three regiments. One of the original regiments was dispersed amongst the others, which were then named after three of the Spanish cities that volunteers largely originated from—Madrid, Valencia and Seville. Each regiment had three battalions (of four companies each) and two weapons companies, supported by an artillery regiment of four battalions (of three batteries each). There were enough men left over to create an assault battalion, mainly sub-machine gun armed. Later, due to casualties, this was disbanded. Aviator volunteers formed a Blue Squadron (Escuadrillas Azules) which, using Bf 109s and FW 190s, was credited with 156 Soviet aircraft kills.

Eastern Front

.jpg)

On 31 July, after taking the Hitler oath,[4] the Blue Division was formally incorporated into the German Wehrmacht as the 250th Division.[5] It was initially assigned to Army Group Center, the force advancing towards Moscow. The division was transported by train to Suwałki, Poland (August 28), from where it had to continue by foot on a 900 km march. It was scheduled to travel through Grodno (Belarus), Lida (Belarus), Vilnius (Lithuania), Molodechno (Belarus), Minsk (Belarus), Orsha (Belarus) to Smolensk, and from there to the Moscow front. While marching towards the Smolensk front on September 26, the Spanish volunteers were rerouted from Vitebsk and reassigned to Army Group North (the force closing on Leningrad), becoming part of the German 16th Army. The Blue Division was first deployed on the Volkhov River front, with its headquarters in Grigorovo, on the outskirts of Novgorod. It was in charge of a 50 km section of the front north and south of Novgorod, along the banks of the Volkhov River and Lake Ilmen.

The iconostasis of the Church of Saint Theodore Stratelates on the Brook was used for firewood by the division's soldiers. The iconostases of the Orthodox Cathedral of Saint Sophia, Sts. Peter and Paul Church in Kozhevniki, and the Cathedral of the Nativity of the Mother of God in the Antoniev Monastery were taken to Germany at the end of 1943.[6] According to the museum curator in the Church of the Transfiguration on Ilyina Street, the division used the high cupola as a machine-gun nest. As a result, much of the building was seriously damaged, including many of the medieval icons by Theophanes the Greek.

In August 1942, it was transferred north to the southeastern flank of the Siege of Leningrad, just south of the Neva near Pushkin, Kolpino and Krasny Bor in the Izhora River area. After the collapse of the German southern front following the Battle of Stalingrad, more German troops were deployed southwards. By this time, General Emilio Esteban Infantes had taken command. The Blue Division faced a major Soviet attempt to break the siege of Leningrad in February 1943, when the 55th Army of the Soviet forces, reinvigorated after the victory at Stalingrad, attacked the Spanish positions at the Battle of Krasny Bor, near the main Moscow-Leningrad road. Despite very heavy casualties, the Spaniards were able to hold their ground against a Soviet force seven times larger and supported by tanks. The assault was contained and the siege of Leningrad was maintained for a further year. The division remained on the Leningrad front where it continued to suffer heavy casualties due to weather and to enemy action.[7]

Disbandment and the Blue Legion

Eventually, the Allies and conservative Spaniards (including many officials of the Catholic Church) began to press Franco for the withdrawal of troops from the quasi-alliance with Germany. Franco initiated negotiations in the spring of 1943 and gave an order of withdrawal on October 10. Some Spanish volunteers refused to return. On November 3, 1943 the Spanish government ordered all troops to return to Spain. In the end, the total of "non returners" was close to 3,000 men, mostly Falangists. Spaniards also joined other German units, mainly the Waffen-SS, and fresh volunteers slipped across the Spanish border near Lourdes in occupied France. The new pro-German units were collectively called the Legión Azul ("Blue Legion").

Spaniards initially remained part of the 121st Infantry Division, but even this meagre force was ordered to return home in March 1944,[8] and was transported back to Spain on March 21. The rest of the volunteers were absorbed into German units. Platoons of Spaniards served in the 3rd Mountain Division and the 357th Infantry Division. One unit was sent to Latvia. Two companies joined the Brandenburger Regiment and German 121st Division in Nazi security warfare in Yugoslavia. The 101st Company (Spanische-Freiwilligen Kompanie der SS 101, "Spanish Volunteer Company of the SS Number 101") of 140 men, made up of four rifle platoons and one staff platoon, was attached to 28th SS Volunteer Grenadier Division Wallonien.

The Blue Division was the only component of the German Army to be awarded a medal of their own, commissioned by Hitler in January 1944 after the Division had demonstrated its effectiveness in impeding the advance of the Red Army.[9] Hitler referred to the division as "equal to the best German ones". During his table talks, he said: "...the Spaniards have never yielded an inch of ground. One can't imagine more fearless fellows. They scarcely take cover. They flout death. I know, in any case, that our men are always glad to have Spaniards as neighbours in their sector.[10]

Through rotation, as many as 45,482 Spanish soldiers served on the Eastern Front. The casualties of the Blue Division and its successors included 4,954 men killed and 8,700 wounded. Another 372 members of the Blue Division, the Blue Legion, or volunteers of the Spanische-Freiwilligen Kompanie der SS 101 were taken prisoner by the victorious Red Army; 286 of these men were kept in captivity until April 2, 1954, when they returned to Spain aboard the ship Semiramis, supplied by the International Red Cross.[11]

Order of battle

- July 1941

- 262nd, 263rd, and 269th Infantry Regiments

- 250th Artillery Regiment of four battalions (1 thru 4)

- 250th Panzerjäger Battalion

- 250th Reconnaissance Battalion

- 250th Feldersatz (replacement) Battalion

- 250th Pioneer Battalion

- 250th Signals Battalion

- Supply Troops

- September 1943

- 262nd, 263rd, and 269th Grenadier Regiments

- 250th Artillery Regiment of four battalions (1 thru 4)

- 250th Panzerjäger Battalion

- 250th Reconnaissance Battalion

- 250th Pioneer Battalion

- 250th Signals Battalion

- Supply Troops

After the war

Many of the generals who perpetrated the attempted coup d'état against the Spanish government on February 23, 1981 had served in the Blue Division during World War II. Amongst them were generals Alfonso Armada and Jaime Milans del Bosch. Other Blue Division veterans, including Director of the Guardia Civil José Luis Aramburu Topete and José Gabeiras, remained loyal to the legal democratic government under the young King Juan Carlos I of Spain.

Foreign fighters in the Blue Division

Regarding Portugal, although some sectors of public opinion with anti-communist sentiments have had some sympathy for the Blue Division, however the always prudent and cautious president of the government, António de Oliveira Salazar, managed to dominate the most radical sectors and prevent the formation of a Portuguese unit. Despite Portugal's neutrality about one hundred and fifty Portuguese soldiers fought in the Blue Division, However these Portuguese were mainly Portuguese with roots in Spain and who had already fought on the Franco side in the Viriatos division during the Spanish Civil War. These Portuguese fought integrated in the Spanish ranks and at no time did they create any type of subunit with its own identity.[12]

See also

- Spain in World War II

Notes

- English: "No possible relief, until extinction"

References

- Clodfelter, Micheal (2017). Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Encyclopedia of Casualty and Other Figures, 1492-2015 (4 ed.). McFarland. p. 456. ISBN 978-0786474707.

- Carlos Caballero Jurado; Ramiro Bujeiro (2009). Blue Division Soldier 1941-45: Spanish Volunteer on the Eastern Front. Osprey Publishing. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-84603-412-1.

- Gerald R. Kleinfeld and Lewis A. Tambs, "North To Russia: The Spanish Blue Division In World War II" Military Affairs (1973) 37#1 8+.

- Arnold Krammer. Spanish Volunteers against Bolshevism: The Blue Division. Russian Review, Vol. 32, No. 4 (Oct., 1973), pp. 388–402

- David Wingeate Pike. Franco and the Axis Stigma. Journal of Contemporary History, Vol. 17, No. 3 (Jul., 1982), pp. 369–407

- 11th - 19th Century Russian Icons in the Collection of the National Museum Complex in Veliky Novgorod (page 9), Exhibition Guidebook, Veliky Novgorod - 2018, Saint Petersburg: Lubavich 2018, 216 pages, illustrated, ISBN 978-5-86983-862-9

- Gavrilov, B.I., Tragedy and Feat of the 2nd Shock Army, defunct site paper

- Wendel, Marcus. "Tactical Headquarters Bjelovar (Croatia)".

- Stanley G. Payne; Delia Contreras (1996). España y la Segunda Guerra Mundial. EDITORIAL COMPLUTENSE S.A. p. 85. ISBN 978-84-89365-89-6.

- Norman Cameron and R.H. Stevens (translators). Hitler's Table Talk 1941–1944: His Private Conversations. Enigma Books. New York, 2000. p. 179.

- Candil, Anthony J. "Post: Division Azul Histories and Memoirs". WAIS - World Association for International Studies. Retrieved 3 June 2014.

- Carlos Caballero 2019.

Further reading

- Caballero Jurado, Carlos (2019). La División Azul: Historia completa de los voluntarios españoles de Hitler. De 1941 a la actualidad (in Spanish). Spain: La Esfera de los Libros. ISBN 9788491646068.

- Bowen, Wayne H. BowenSpaniards and Nazi Germany: Collaboration in the New Order. University of Missouri Press (2005), 250 pages, ISBN 0-8262-1300-6.

- Kleinfeld, Gerald R., and Lewis A. Tambs. Hitler's Spanish Legion: The Blue Division in Russia. (Southern Illinois University Press, 1979), 434 pages, ISBN 0-8093-0865-7.

- Morales, Gustavo, & Luis Togores, "La División Azul: las fotografías de una historia". La Esfera de los Libros, Madrid, 2009, second edition.

- Moreno Juliá, Xavier. La División Azul: Sangre española en Rusia, 1941–1945. Barcelona: Crítica (2005).

- Núñez Seixas, Xosé M. "Russia and the Russians in the Eyes of the Spanish Blue Division soldiers, 1941–4." Journal of Contemporary History 52.2 (2017): 352-374. online

- Rusia no es cuestión de un día.... Juan Eugenio Blanco. Publicaciones Españolas. Madrid, 1954

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Blue Division. |