Sanguinaria

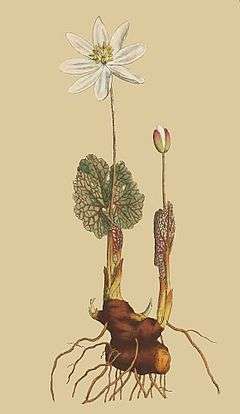

Sanguinaria canadensis, bloodroot,[1] is a perennial, herbaceous flowering plant native to eastern North America. It is the only species in the genus Sanguinaria, included in the family Papaveraceae, and most closely related to Eomecon of eastern Asia.

| Bloodroot Sanguinaria canadensis | |

|---|---|

.jpeg) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Order: | Ranunculales |

| Family: | Papaveraceae |

| Subfamily: | Papaveroideae |

| Tribe: | Chelidonieae |

| Genus: | Sanguinaria L. |

| Species: | S. canadensis |

| Binomial name | |

| Sanguinaria canadensis L. | |

Sanguinaria canadensis is also known as Canada puccoon,[2] bloodwort,[1] redroot,[1] red puccoon,[1] and sometimes pauson. It has also been known as tetterwort,[1] although that name is also used to refer to Chelidonium majus. Plants are variable in leaf and flower shape and have in the past been separated out as different subspecies due to these variable shapes. Currently most taxonomic treatments include these different forms in one highly variable species. In bloodroot, the juice is red and poisonous.[3]

Description

Bloodroot grows from 20 to 50 cm (8 to 20 in) tall. It has one large basal leaf, up to 25 cm (10 in) across, with five to seven lobes.[4] The leaves and flowers sprout from a reddish rhizome with bright orange sap that grows at or slightly below the soil surface. The color of the sap is the reason for the genus name Sanguinaria, from Latin sanguinarius "bloody".[5] The rhizomes grow longer each year, and branch to form colonies. Plants start to bloom before the foliage unfolds in early spring. After blooming the leaves unfurl to their full size and go summer dormant in mid to late summer, later than some other spring ephemerals.

The flowers bloom from March to May depending on the region and weather. They have 8–12 delicate white petals, many yellow stamens, and two sepals below the petals, which fall off after the flowers open. Each flower stem is clasped by a leaf as it emerges from the ground. The flowers open when they are in sunlight.[6] They are pollinated by small bees and flies. Seeds develop in green pods 4 to 6 cm (1 1⁄2 to 2 1⁄4 in) long, and ripen before the foliage goes dormant. The seeds are round and black to orange-red when ripe, and have white elaiosomes, which are eaten by ants.

- Stages in the life of bloodroot

Leaves clasping the flower stems in early spring

Leaves clasping the flower stems in early spring- White petals and yellow stamens

Fruit (a pod holding the seeds) in early summer

Fruit (a pod holding the seeds) in early summer.jpg) Leaves after flowering

Leaves after flowering A carpet of leaves in late spring

A carpet of leaves in late spring- Rhizomes with orange flesh

Distribution and habitat

Bloodroot is native to eastern North America from Nova Scotia, Canada southward to Florida, United States, and west to Great Lakes and down the Mississippi embayment.

Sanguinaria canadensis plants are found growing in moist to dry woods and thickets, often on floodplains and near shores or streams on slopes. They grow less frequently in clearings and meadows or on dunes, and are rarely found in disturbed sites. Deer will feed on the plants in early spring.

Ecology

Bloodroot is one of many plants whose seeds are spread by ants, a process called myrmecochory. The seeds have a fleshy organ called an elaiosome that attracts ants. The ants take the seeds to their nest, where they eat the elaiosomes, and put the seeds in their nest debris, where they are protected until they germinate. They also benefit from growing in a medium made richer by the ant nest debris.

The flowers produce pollen, but no nectar. Various bees and flies visit the flowers looking in vain for nectar, for instance sweat bees in the genera Lasioglossum and Halictus, cuckoo bees in the genus Nomada, small carpenter bees (Ceratina), and bee flies in the genus Bombylius. Some bees come to collect pollen, including mining bees (Andrena), which are the most effective pollinators.[7][8]

The bitter and toxic leaves and rhizomes are not often eaten by mammalian herbivores.[8]

Cultivation

Sanguinaria canadensis is cultivated as an ornamental plant. The double-flowered forms are prized by gardeners for their large showy white flowers, which are produced very early in the gardening season. Bloodroot flower petals are shed within a day or two of pollination, so the flower display is short-lived, but the double forms bloom much longer than the normal forms. The double flowers are made up of stamens that have been changed into petal-like parts, making pollination more difficult.

The double-flowered cultivar S. canadensis f. multiplex 'Plena' has gained the Royal Horticultural Society's Award of Garden Merit.[9][10]

Toxicity

Bloodroot produces benzylisoquinoline alkaloids, primarily the toxin sanguinarine. The alkaloids are transported to and stored in the rhizome.

Sanguinarine kills animal cells by blocking the action of Na+/K+-ATPase transmembrane proteins. As a result, applying bloodroot to the skin may destroy tissue and lead to the formation of necrotic tissue, called an eschar. Bloodroot and its extracts are thus considered escharotic. Although applying escharotic agents (including bloodroot) to the skin is sometimes suggested as a home treatment for skin cancer, these attempts can be severely disfiguring.[11] Salves, most notably black salve, derived from bloodroot do not remove tumors. Microscopic tumor deposits may remain after visible tumor tissue is burned away, and case reports have shown that in such instances tumor has recurred and/or metastasized.[12]

Internal use is not recommended.[13] An overdose of bloodroot extract can cause vomiting and loss of consciousness.[13]

Alkaloid biosynthesis

Comparing the biosynthesis of morphine and sanguinarine, the final intermediate in common is (S)-reticuline.[14][15] A number of plants in Papaveraceae and Ranunculaceae, as well as plants in the genus Colchicum (family Colchicaceae) and genus Chondodendron (family Menispermaceae), also produce such benzylisoquinoline alkaloids. Plant geneticists have identified and sequenced genes which produce the enzymes required for this production. One enzyme involved is N-methylcoclaurine 3'-monooxygenase,[16] which produces (S)-3'-hydroxy-N-methylcoclaurine and mendococlaurine from (S)-N-methylcoclaurine.

Uses

Alternative medicine

Bloodroot was used historically by Native Americans for curative properties as an emetic, respiratory aid, and other treatments.[17]

In physician William Cook's 1869 work The Physiomedical Dispensatory is a chapter on the uses and preparations of bloodroot,[18] which described tinctures and extractions, and also included the following cautionary report:

The U. S. Dispensatory says four persons lost their lives at Bellevue Hospital, New York, by drinking largely of blood root tincture in mistake for ardent spirits ...

Greater celandine (Chelidonium majus), a member of the poppy family, was used in colonial America as a wart remedy. Bloodroot has been similarly applied in the past. This may explain the multiple American and British definitions of "tetterwort" .

Bloodroot extracts have also been promoted by some supplement companies as a treatment or cure for cancer, but the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has listed some of these products among its "187 Fake Cancer 'Cures' Consumers Should Avoid".[19] Oral use of products containing bloodroot are strongly associated with the development of oral leukoplakia,[20] which is a premalignant lesion that may develop into oral cancer. However, a review by Canadian scientists in the journal Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology found that there was no evidence that these products cause leukoplakia, and that the study claiming such cause suffered from selection and information bias, and from potential confounding.[21]

This plant has also been used in medical quackery, as was evidenced by the special product produced by Dr. John Henry Pinkard during the 1920s and 1930s. Some bottles of "Pinkard's Sanguinaria Compound", made from bloodroot or bloodwort, were seized by federal officials in 1931. "Analysis by this department of a sample of the article showed that it consisted essentially of extracts of plant drugs including sanguinaria, sugar, alcohol, and water. It was alleged in the information that the article was misbranded in that certain statements, designs, and devices regarding the therapeutic and curative effects of the article, appearing on the bottle label, falsely and fraudulently represented that it would be effective as a treatment, remedy, and cure for pneumonia, coughs, weak lungs, asthma, kidney, liver, bladder, or any stomach troubles, and effective as a great blood and nerve tonic." John Henry Pinkard plead guilty and was fined $25.00.[22]

Commercial uses

Commercial uses of sanguinarine and bloodroot extract include dental hygiene products. The United States FDA has approved the inclusion of sanguinarine in toothpastes as an antibacterial or anti-plaque agent.[23][24][25][26] However, the use of sanguinaria in oral hygiene products is associated with the development of a premalignant oral leukoplakia,which may develop into oral cancer.[20][27] In 2003, the Colgate-Palmolive Company of Piscataway, New Jersey, United States commented by memorandum to the United States Food and Drug Administration that then-proposed rules for levels of sanguinarine in mouthwash and dental wash products were lower than necessary.[28] However, this conclusion is controversial.[29]

Some animal food additives sold and distributed in Europe contain sanguinarine and chelerythrine.

Plant dye

Bloodroot is a popular red natural dye used by Native American artists, especially among southeastern rivercane basketmakers.[30] A break in the surface of the plant, especially the roots, reveals a reddish sap which can be used as a dye.

References

- "Sanguinaria canadensis". Germplasm Resources Information Network (GRIN). Agricultural Research Service (ARS), United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- "RHS Plantfinder - Sanguinaria canadensis". Retrieved 28 October 2018.

- "Bloodroot Wildflowers". Wild Flowers Guide. Archived from the original on 2014-08-21.

- Kiger, Robert W. (1997). "Sanguinaria canadensis". In Flora of North America Editorial Committee (ed.). Flora of North America North of Mexico (FNA). 3. New York and Oxford – via eFloras.org, Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, MO & Harvard University Herbaria, Cambridge, MA.

- Kiger, Robert W. (1997). "Sanguinaria". In Flora of North America Editorial Committee (ed.). Flora of North America North of Mexico (FNA). 3. New York and Oxford – via eFloras.org, Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, MO & Harvard University Herbaria, Cambridge, MA.

- "Bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis)". Prairie Nursery.

- Heather Holm (2014). Pollinators on Native Plants. Minnetonka, MN: Pollinator Press. pp. 164–165.

- Hilty, John (2016). "Bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis)". Illinois Wildflowers.

- "RHS Plant Selector – Sanguinaria canadensis f. multiplex 'Plena'". Retrieved 23 February 2020.

- "AGM Plants - Ornamental" (PDF). Royal Horticultural Society. July 2017. p. 94. Retrieved 28 October 2018.

- Don't Use Corrosive Cancer Salves (Escharotics), Stephen Barrett, M.D.

- McDaniel, S.; Goldman, GD (2002). "Consequences of Using Escharotic Agents as Primary Treatment for Nonmelanoma Skin Cancer". Archives of Dermatology. 138 (12): 1593–6. doi:10.1001/archderm.138.12.1593. PMID 12472348.

- "Bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis L.)". Horticulture Information Leaflets. NC State Extension Publications.

- Alcantara, Joenel; Bird, David A.; Franceschi, Vincent R.; Facchini, Peter J. (2005). "Sanguinarine Biosynthesis is Associated with the Endoplasmic Reticulum in Cultured Opium Poppy Cells after Elicitor Treatment". Plant Physiology. 138 (1): 173–83. doi:10.1104/pp.105.059287. JSTOR 4629815. PMC 1104173. PMID 15849302.

- "PATHWAY: Alkaloid biosynthesis I – Reference pathway". Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG).

- "ENZYME: 1.14.13.71". Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG).

- Native American Ethnobotany (University of Michigan – Dearborn: Sanguinaria canadensis . accessed 12.1.2011

- Sanguinaria Canadensis. | Henriette's Herbal Homepage

- "187 Fake Cancer "Cures" Consumers Should Avoid". United States Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 2019-08-18.

- Bouquot, Brad W. Neville , Douglas D. Damm, Carl M. Allen, Jerry E. (2002). Oral & maxillofacial pathology (2. ed.). Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders. p. 338. ISBN 0721690033.

- Ic, Munro; Es, Delzell; Er, Nestmann; Bs, Lynch (30 December 1999). "Viadent Usage and Oral Leukoplakia: A Spurious Association". Regulatory toxicology and pharmacology : RTP. PMID 10620468. Retrieved 2020-06-05.

- Case #19890. Misbranding of Pinkard's sanguinaria compound. U. S. v. John Henry Pinkard. Plea of guilty. Fine, $25.

- Godowski, KC (1989). "Antimicrobial action of sanguinarine". The Journal of clinical dentistry. 1 (4): 96–101. PMID 2700895.

- Southard, GL; Boulware, RT; Walborn, DR; Groznik, WJ; Thorne, EE; Yankell, SL (1984). "Sanguinarine, a new antiplaque agent: Retention and plaque specificity". Journal of the American Dental Association. 108 (3): 338–41. doi:10.14219/jada.archive.1984.0022. PMID 6585404.

- How to Report Problems With Products Regulated by FDA

- Kuftinec, MM; Mueller-Joseph, LJ; Kopczyk, RA (1990). "Sanguinaria toothpaste and oral rinse regimen clinical efficacy in short- and long-term trials". Journal of the Canadian Dental Association. 56 (7 Suppl): 31–3. PMID 2207852.

- Leukoplakia Archived 2007-01-07 at the Wayback Machine, hosted by the American Academy of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. Page accessed on December 19, 2006.

- Letter to FDA, Collgate-Palmolive Company, 24 Nov. 2003

- Letter to FDA, Professor George T. Gallagher, Boston University Goldman School of Dental Medicine, 23 June 2003.

- Nolan, Justin. "Northeast Oklahoma, USA." Society of Ethnobotany. 2007 (retrieved 9 Jan 2011)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sanguinaria. |

- Flora of North America: Distribution map

- Connecticut Plants, Connecticut Botanical Society