Bikkurim (First-fruits)

In Ancient Israel, the First-fruits (Hebrew: בכורים) or Bikkurim (/bɪˌkuːˈriːm, bɪˈkʊərɪm/)[1] were a type of offering that were akin to, but distinct from, terumah gedolah. While terumah gedolah was an agricultural tithe, the First-fruits, discussed in the Bikkurim tractate of the Talmud, were a sacrificial gift brought up to the altar (Bikkurim 3:12). The major obligation to bring First Fruits (henceforth Bikkurim) to the Temple began at the festival of Shavuot and continued until the festival of Sukkot (Bikkurim 1:6). This tithe was limited to the traditional seven agricultural products (wheat, barley, grapes in the form of wine, figs, pomegranates, olives in the form of oil, and dates) grown in Israel.[2] This tithe, and the associated festival of Shavuot, is legislated by the Torah.[3] Textual critics speculate that these regulations were imposed long after the offerings and festival had developed.[4]

By the time of classical antiquity, extensive regulations regarding Bikkurim were recorded in the classical rabbinical literature.[5] According to Jewish law, the corners of fields, wild areas, left-overs after harvesting (gleanings), and unowned crops were not subjected to (and could not be used as) the tithe of First Fruits (they were intended to be left as charity for the poor, and other mendicants);[2] plants from outside Israel were also prohibited from inclusion in the tithe,[2] as was anything belonging to non-Jews.[6] The rules also specify that each type of product had to be individually tithed, even if the numbers were balanced so that there was no difference in amount between this situation and using just some types of First Fruit as the tithe, and retaining others in their entirety.[2] Fruit which was allocated to the tithe could not be swapped for fruit which wasn't, to the extent that wine couldn't be swapped for vinegar, and olive oil couldn't be replaced by olives; furthermore, fruits were not allowed to be individually divided if only part went to the tithe (small whole pomegranates had to be used rather than sections from a large pomegranate, for example).[2]

The separation of tithed produce from untithed produce was also subject to regulation. The individual(s) separating one from the other had to be ritually clean, and had to include the best produce in the tithe if a kohen (priest) lived nearby.[2] During the act of separation, the produce was not permitted to be counted out to determine which fell under the tithe, nor to be weighed for that purpose, nor to be measured for the same reason, but instead the proportion that was to become the tithe had to be guessed at.[2] In certain situations, such as when tithed produce became mixed with non-tithed produce (or there was uncertainty as to whether it had), the tithed produce had to be destroyed.[2] Anyone who made mistakes in the separation of tithed produce, and anyone who consumed any of the tithe, was required to pay compensation as a guilt offering.[2]

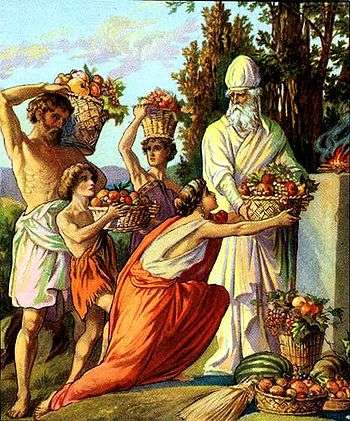

The pilgrims that brought the Bikkurim to the Temple were obligated to recite a declaration, also known as the Avowal, set forth in Deuteronomy 26:3-10 (cf. Mishnah, Bikkurim 3:6). Native-born Israelites and proselytes would bring the Bikkurim and would say the Avowal, but women who brought the Bikkurim were not permitted to say the Avowal, since they were unable to claim inheritance in the Land bequeathed unto the tribes by their male lineage.[lower-alpha 1] This Avowal was incorporated into a beautiful and grand festive celebration with a procession of pilgrims marching up to Jerusalem and then the Temple with gold, silver or willow baskets to which live doves were tied. (Bikkurim 3:3,5 and 8). The pilgrims were led by flutists to the city of Jerusalem where they were greeted by dignitaries (Bikkurim 3:3). The procession would then resume with the flutist in lead until the Temple Mount where the Levites would break out in song (Bikkurim 3:4). The doves were given as sacrificial offerings and the declaration would be made before a priest while the basket was still on the pilgrim's shoulder (Bikkurim 3:5-6). After the basket was presented to the priest, it was placed by the Altar and the pilgrim would bow and leave (Bikkurim 3:6).

A prerequisite for bringing the Bikkurim is that the person who brings them is the legal property owner of the land on which the fruits were grown, for which reason, share-croppers and usurping occupants were not permitted to bring them.[8]

Ceremonial ritual

The following was the method of selecting fruits for the offering: Upon visiting his field and seeing a fig, or a grape, or a pomegranate that was ripe, the owner would tie a cord of reed-grass or similar fiber around the fruit, saying, "This shall be among the bikkurim." According to Simeon, he had to repeat the express designation after the fruit had been plucked from the tree in the orchard (Mishnah, Bikkurim 3:1). The fruits were carried in great state to Jerusalem. Stations (Heb. ma'amadot), with deputations representing the people of all the cities in the district, assembled in the chief town of the district, and stayed there overnight in the open squares, without going into the houses. At dawn the officer in charge (Heb. memunneh) called out: "Arise, let us ascend to Zion, the house of the Lord our God." Those from the neighborhood brought fresh figs and grapes, those from a distance dried figs and raisins.

The bull destined for the sacrifice, his horns gilded and his head wreathed with olive-leaves, led the procession, which was accompanied with flute-playing. When they arrived near the Holy City, the pilgrims sent messengers ahead while they decorated the Firstfruits. The Temple officers came out to meet them, and all artisans along the streets rose before them, giving them the salutation of peace, and hailing them as brothers from this or that town. The flute kept sounding until they reached the Temple mount. Here even King Agrippa, following the custom, took his basket on his shoulder, and marched in the ranks, until they came to the outer court and hall. There they were welcomed by the Levites, singing Psalm 30:2. The doves which had been carried along in the baskets were offered for burnt offerings, and what the men had in their hands they gave to the priests. But before this, while still carrying his basket, each man recited Deuteronomy 26:3 et seq.; at the words "an oppressed Aramæan was my father,"[9] the basket was deposed from the shoulder, but while the owner was still holding its handles or rims, a priest put his hand under it and "swung it" (lifted it up), and repeated the words "an oppressed Aramæan was my father," etc., to the close of the Deuteronomic section. Then placing the basket by the side of the altar, the pilgrim bowed down and left the hall.

See also

- Bikkurim (Talmud)

References

- "bikkurim". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

- Singer, Isidore, ed. (1901) Jewish Encyclopedia (Funk and Wagnals) ASIN: B000B68W5S s.v. "Heave-Offering"

- Exodus 23:16-19; Leviticus 23:9; Deuteronomy 26:2; et al.

- Friedman, Richard Elliott (1997), Who Wrote the Bible? HarperOne. ISBN 978-0-06-063035-5

- Black, Matthew, ed. (2001), Peake's commentary on the Bible, Routledge ISBN 978-0-415-26355-9

- Singer, ed., Jewish Encyclopedia, s.v. "Sacrifice"

- Ben Maimon, Moshe (1974). Mishne Torah (Hil. Bikkurim 4:1–3) (in Hebrew). 4. Jerusalem: Pe'er ha-Torah. pp. 132–133.

- Mishnah, Bikkurim 1:2

- Typically translated in many English texts, "a wayfaring Aramæan was my father," but explained in the Aramaic Targum to mean "an oppressed Aramaean was my father."

- Mishnah Bikkurim 1:4, disputing, says that proselytes who brought the Bikkurim could not say the Avowal, seeing that they were not true descendants of Jacob the Patriarch and had no inheritance in the Land, though the Avowal would have them say, "Which the Lord sware unto our Fathers for to give us" (Deut. 26:3). Moreover, the Avowal makes use of the words, "an oppressed Aramæan was my father" (Deut. 26:5), explained there in the Aramaic Targum of Onkelos to mean that Jacob, the progenitor of the Israelite nation, was persecuted by Laban the Aramaean, who sought to destroy him. Maimonides, in his Code of Jewish law, makes it clear that the Avowal was also stated by proselytes, ruling in accordance with the Jerusalem Talmud, and where it is explained that although they cannot claim physical descent from Jacob the Patriarch, they could still claim to be of Abraham's progeny, since the Torah testifies retrospectively of him that he will become "the Father of many nations" (Gen. 17:5). Moreover, even proselytes had a portion in the Land, by virtue of the Torah allowing them to be allotted land in the suburbs of the cities occupied by the tribes (cf. Ezekiel 47:21-23).[7]