Beja, Portugal

Beja (Portuguese pronunciation: [ˈbɛʒɐ] (![]()

Beja | |

|---|---|

.jpg)  _(cropped).jpg) .jpg) | |

Flag  Coat of arms | |

| |

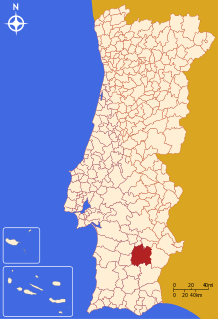

| Coordinates: 38°02′N 7°53′W | |

| Country | |

| Region | Alentejo |

| Intermunic. comm. | Baixo Alentejo |

| District | Beja |

| Parishes | 11 |

| Government | |

| • President | Paulo Arsénio (PS) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 1,146.44 km2 (442.64 sq mi) |

| Population (2011) | |

| • Total | 35,854 |

| • Density | 31/km2 (81/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC±00:00 (WET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+01:00 (WEST) |

| Local holiday | Ascension Day (date varies) |

| Website | http://www.cm-beja.pt |

The municipality is the capital of the Beja District. The present Mayor is Paulo Arsénio, elected by the Socialist Party with an absolute majority in the 2017 Portuguese Local Elections.[4] The municipal holiday is Ascension Day. The Portuguese Air Force has an airbase in the area – the Air Base No. 11.

History

Situated on a 277-metre (909 ft) hill, commanding a strategic position over the vast plains of the Baixo Alentejo, Beja was already an important place in antiquity. Already inhabited in Celtic times,[5] the town was later named Pax Julia by Julius Caesar in 48 BCE, when he made peace with the Lusitanians. He raised the town to be the capital of the southernmost province of Lusitania (Santarém and Braga were the other capitals of the conventi). During the reign of emperor Augustus the thriving town became Pax Augusta. It was already then a strategic road junction.

When the Visigoths took over the region, the town, then called Paca, became the seat of a bishopric. Saint Aprígio (died in 530) became the first Visigothic bishop of Paca. The town fell to the invading Umayyad army in 713. Thus Paca, through Arabic Baja (Arabic: باجة there's no sound for "p" in Arabic), became Beja.

Starting in 910 there were successive attempts of conquest and reconquest by the Christian kings. With the collapse of the Umayyad Caliphate of Córdoba in 1031, Beja became a taifa, an independent Muslim-ruled principality. In 1144 the governor of Beja (Arabic: باجة الزيت), Sidray ibn Wazir, helped the rebellion of the Murīdūn (disciples) led by Abul-Qasim Ahmad ibn al-Husayn al-Quasi in the Algarve against power of Seville. In 1150 the town was captured by an army of the Almohads, who annexed it to their North African empire. It was retaken in 1162 by Fernão Gonçalves, leading the army of the Portuguese king Afonso I. In 1175 Beja was recaptured again by the Almohads. It stayed under Muslim rule till 1234 when king Sancho II finally recaptured the town from the Moors.

All these wars depopulated the town and gradually reduced it to rubble. Only with Manuel I in 1521 did Beja again reach the status of city. It was attacked and occupied by the Portuguese and the Spanish armies during the Portuguese Restoration War (1640–1667).

Beja became again the head of a bishopric in 1770, more than a thousand years after the fall of the Visigothic city. In 1808 Napoleonic troops under General Junot sacked the city and massacred the inhabitants.

Geography

Climate

Due to its southernmost location with the descending winds of the subtropics, low precipitation, especially in summer and far from the coast makes the city a hot-summer Mediterranean climate (Köppen: Csa)[6] and therefore is the hottest city of Portugal and one of the hottest of the Iberian Peninsula in the maximum temperatures. Between 2001 and 2018 it had the hottest summer of any city in the country, hotter than other cities like Évora, Lisbon or Porto. Although mild by European standards, Beja has relatively cool winters, while summers are long and hot. The high in January is around 14 °C (57 °F) while the July and August highs are around 33 °C (91 °F). Snow is rare but may occur on a few occasions in a century, the last being on January 10, 2019.[7] The January low is 5 °C (41 °F) and in July and August is 16 °C (61 °F). The annual mean is around 17 °C (63 °F). The average total rainfall in a year is 558 mm (22.0 in).[8][9][10][11] The year 2005 was particularly dry in Portugal and Beja suffered devastating forest fires in the surrounding rural areas which contributes to desertification in the Alentejo.[12][13]

| Climate data for Beja (Santiago Maior), elevation: 247 m or 810 ft, 1961-1990 normals and extremes | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 22.0 (71.6) |

24.1 (75.4) |

28.8 (83.8) |

29.8 (85.6) |

36.7 (98.1) |

43.3 (109.9) |

42.7 (108.9) |

41.4 (106.5) |

42.0 (107.6) |

34.3 (93.7) |

28.1 (82.6) |

21.2 (70.2) |

43.3 (109.9) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 13.8 (56.8) |

14.9 (58.8) |

17.3 (63.1) |

19.4 (66.9) |

23.7 (74.7) |

28.4 (83.1) |

32.5 (90.5) |

32.5 (90.5) |

29.3 (84.7) |

23.2 (73.8) |

17.5 (63.5) |

14.2 (57.6) |

22.2 (72.0) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 9.6 (49.3) |

10.4 (50.7) |

11.9 (53.4) |

13.7 (56.7) |

16.9 (62.4) |

20.8 (69.4) |

23.8 (74.8) |

24.0 (75.2) |

22.2 (72.0) |

17.7 (63.9) |

13.0 (55.4) |

10.1 (50.2) |

16.2 (61.1) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 5.4 (41.7) |

5.9 (42.6) |

6.6 (43.9) |

7.9 (46.2) |

10.1 (50.2) |

13.2 (55.8) |

15.1 (59.2) |

15.4 (59.7) |

15.1 (59.2) |

12.3 (54.1) |

8.5 (47.3) |

6.0 (42.8) |

10.1 (50.2) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −3.0 (26.6) |

−4.0 (24.8) |

−2.8 (27.0) |

0.3 (32.5) |

2.3 (36.1) |

6.2 (43.2) |

9.1 (48.4) |

9.0 (48.2) |

6.4 (43.5) |

3.2 (37.8) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

−4.9 (23.2) |

−4.9 (23.2) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 81.0 (3.19) |

80.0 (3.15) |

54.0 (2.13) |

60.0 (2.36) |

36.0 (1.42) |

23.0 (0.91) |

2.0 (0.08) |

3.0 (0.12) |

22.0 (0.87) |

65.0 (2.56) |

76.0 (2.99) |

83.0 (3.27) |

585 (23.05) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 9.0 | 10.0 | 7.0 | 7.0 | 6.0 | 3.0 | trace | 1.0 | 2.0 | 6.0 | 8.0 | 9.0 | 68 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 81.0 | 79.0 | 72.0 | 70.0 | 64.0 | 56.0 | 50.0 | 50.0 | 56.0 | 68.0 | 76.0 | 81.0 | 66.9 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 148.0 | 147.0 | 195.0 | 219.0 | 282.0 | 298.0 | 357.0 | 336.0 | 245.0 | 199.0 | 158.0 | 142.0 | 2,726 |

| Source: NOAA[14] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Beja (Santiago Maior), elevation: 246 m or 807 ft, 1981-2010 normal, 1981-present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 22.0 (71.6) |

24.5 (76.1) |

30.0 (86.0) |

32.6 (90.7) |

37.2 (99.0) |

45.4 (113.7) |

45.2 (113.4) |

45.4 (113.7) |

42.0 (107.6) |

35.0 (95.0) |

28.1 (82.6) |

22.0 (71.6) |

45.4 (113.7) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 14.0 (57.2) |

15.5 (59.9) |

19.0 (66.2) |

20.4 (68.7) |

24.3 (75.7) |

29.9 (85.8) |

33.3 (91.9) |

33.1 (91.6) |

29.4 (84.9) |

23.5 (74.3) |

18.0 (64.4) |

14.5 (58.1) |

22.9 (73.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 9.7 (49.5) |

10.8 (51.4) |

13.4 (56.1) |

14.6 (58.3) |

17.7 (63.9) |

22.0 (71.6) |

24.6 (76.3) |

24.8 (76.6) |

22.4 (72.3) |

18.2 (64.8) |

13.6 (56.5) |

10.7 (51.3) |

16.9 (62.4) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 5.4 (41.7) |

6.0 (42.8) |

7.7 (45.9) |

8.7 (47.7) |

11.0 (51.8) |

14.0 (57.2) |

15.8 (60.4) |

16.4 (61.5) |

15.4 (59.7) |

12.9 (55.2) |

9.2 (48.6) |

6.8 (44.2) |

10.8 (51.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −2.7 (27.1) |

−3.2 (26.2) |

−3.2 (26.2) |

0.3 (32.5) |

3.3 (37.9) |

7.6 (45.7) |

8.7 (47.7) |

9.0 (48.2) |

7.5 (45.5) |

3.8 (38.8) |

0.3 (32.5) |

−0.9 (30.4) |

−3.2 (26.2) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 65.7 (2.59) |

55.0 (2.17) |

40.5 (1.59) |

58.8 (2.31) |

43.3 (1.70) |

13.1 (0.52) |

2.4 (0.09) |

4.0 (0.16) |

29.5 (1.16) |

71.5 (2.81) |

76.5 (3.01) |

97.7 (3.85) |

558 (22.0) |

| Source: IPMA[11] | |||||||||||||

Human geography

Administratively, the municipality is divided into 11 civil parishes (freguesias):[15]

Architecture

Castle

The Castle of Beja on top of the hill can be seen from afar and dominates the town. It was built, together with the town walls, under the reign of King Diniz in the 13th century over the remains of a Roman castellum that had been fortified by the Moors. It consists of battlement walls with four square corner towers and a central granite and marble keep (Torre de Menagem), with its height of 40 m the highest in Portugal. The top of the keep can be accessed via a spiral staircase with 197 steps, passing three stellar-vaulted rooms with Gothic windows. The merlons of the machicolation around the keep are topped with small pyramids. Standing on the battlements, one has a sensational panorama of the surrounding landscape. One can also glimpse the remains of the city walls that once had forty turrets and five gates. The castle now houses a small military museum.

The square in front of the castle is named after Gonçalo Mendes da Maia or O Lidador, a brave knight killed in the battle against the Moors in 1170.

Visigothic Museum

The whitewashed Latin-Visigothic church of Santo Amaro, dedicated to Saint Amaro, standing next to the castle, is one of just four pre-Romanesque churches left in Portugal. Some parts date from the 6th century and the interior columns and capitals are carved with foliages and geometric designs from the 7th century. Especially the column with birds attacking a snake is of particular note. It houses today a small archaeological museum with Visigothic art.

Museum of Queen Eleanor

This regional museum was set up in 1927 and 1928 in the former Convent of Our Lady of the Conception (Convento de Nossa Senhora da Conceição) of the Order of Poor Ladies (dissolved in 1834), gradually expanding its collection. This Franciscan convent had been established in 1459 by Infante Fernando, Duke of Viseu and duke of Beja, next to his ducal palace. The construction continued until 1509.

It is an impressive building with a late-Gothic lattice-worked architrave running along the building. This elegant architrave resembles somewhat the architrave of the Monastery of Batalha, even if there are some early-Manueline influences. Above the entrance porch on the western façade one can see the ajimez window (a mullioned window in Manueline and Moorish style) in the room of the abbess, originating from the demolished palace of the dukes of Beja. The entrance door is embedded under an ogee arch. A square bell-tower and a spire with crockets tower above the complex. The convent has been classified as a national monument.

The entrance hall leads to the sumptuously gilded Baroque chapel, consisting of a single nave under a semi-circular vault. Three altars (one of the 17th century, dedicated to St. John the Evangelist, and two of the 18th century, dedicated to St. Christopher and St. Bento) are decorated with gilded woodwork (talha dourada). The fourth altar, dedicated to St. John the Baptist, was decorated with Florentine mosaics by José Ramalho in 1695.

On the wall are three religious azulejos dating from 1741, depicting scenes from the life of St. John the Baptist

The refectory and the claustro are decorated with exquisite azulejos, some dating from Moorish times, others from the 16th to the 18th centuries.

One enters the chapter house through a Manueline portal from the quadra of St. John the Evangelist. The ribbed vault of this square room was distempered during the renovations of 1727. The walls are covered with Arab-Hispanic azulejos with geometric and vegetal designs that are among the most important ceramic decorations in Portugal. Above the azulejos are some semicircular distempered paintings with religious themes: St. John the Baptist, St. John the Evangelist, St. Christopher, St. Clare and St. Francis of Assisi.

The museum houses also an important collection of Flemish, Spanish and Portuguese paintings from the 15th to the 18th centuries, among them:

- Flemish paintings: Virgin with Milk; Flemish School (c. 1530) and "Christ and His Apostles" (16th century)

- Portuguese paintings: Ecce Homo (15th century), "St. Vincent by Vicente Gil and Manuel Vicente (16th century), "Virgin with the Rose" by Francisco Campos (16th century), "Mass of St. Gregory" probably by Gregório Lopes (16th century), "Annunciation" (16th century) and four paintings by António Nogueira (16th century), "Last Supper" by Pedro Alexandrino (17th century).

- Spanish paintings: St. Augustine, St. Jerome and "Martyrdom of St. Bartholomew" by José de Ribera (Spanish, 17th century), Head of Saint John the Baptist (Spanish School, 17th century)

The museum houses also the funeral monuments in late-Gothic style of the first abbess D. Uganda and of the Infante Fernando, Duke of Viseu and his wife Beatriz of Portugal.

The archaeological collection of Fernando Nunes Ribeiro, donated to museum in 1987 after forty years of archaeological research, is on display on the upper floors: Visigothic and Roman artefacts, gravestones from the Bronze Age with antique writings of the Iberians and steles from the Iron Age.

Among the several other artefacts in its collection, the museum possesses the Escudela de Pero de Faria, a unique piece of Chinese porcelain from 1541.

Museums and monuments

- Castle of Beja

- Regional Museum (Housed in the Convent of Beja

- Museological Core of Sembrano's Street

- Visigotic Core of the Regional Museum (Housed in the Church of Santo Amaro)

- Old Stone Pillory

- Roman ruins of Pisões

- Jorge Vieira's Art Museum

Historical churches

- Cathedral of St. James the Great, Beja

- Heritage of Santo André

- Church of Santo Amaro / Visigotic Core of the Regional Beja Museum

- Church of Mercy

- Our Lady of Conception Convent (Convent of Beja) / REGIONAL MUSEUM

- S. Francisco Convent (Now a Historical Hotel)

- Church of Santa Maria da Feira (Originally Built as a Mosque)

- Church of Our Lady of Pleasures

- Church of Our Lady at the Foot of the Cross

- Church of Our Lady of Peace

- Church of the Savior

- Church of Our Lady of Carmo

- St. Stephen's Chapel

- S. Sebastião's Heritage

- Convent of Santo António

Urban green spaces

- Public Garden

- City Park

- Picnic Park (Close to the City Park)

Education

University

- Polytechnic Institute of Beja

Schools

- EB 2,3 Santiago Maior School

- EB 2,3 Mário Beirão School

- EB 2,3 Santa Maria School

- D. Manuel I - High School

- Diogo Gouveia - High School

- Regional Music Conservatory from Baixo Alentejo

Culture

Cultural places

- Beja Public Library

- Pax Julia Theater

- Casa da Culture (meaning House of Culture)

Events

- Ovibeja

- Patrimónios do Sul

- Beja Romana (Historical Recreation from Roman Times)

- International Comics Festival

- Palavras Andarilhas

Notable citizens

- André de Gouveia

- Al-Mu'tamid ibn Abbad

- António de Gouveia

- António Raposo Tavares, O Velho (São Miguel do Pinheiro, Mertola; 1598 – São Paulo, Brazil; 1658), a Portuguese colonial bandeirante who explored the eastern coast of South America (claiming it for Portugal) and extending the territory of the Portuguese colony beyond the limits imposed by the Treaty of Tordesillas;

- António Zambujo

- Diogo de Gouveia

- Queen Eleanor of Viseu

- Fernando Mamede

- Gonçalo Mendes da Maia O Lidador (Maia, 1079 – Alentejo, 1170), Portuguese knight in the service of Afonso Henriques, responsible for border defense in the region of Beja.

- Mariana Alcoforado (Santa Maria da Feira, Beja, 22 April 1640 – Beja, 28 July 1723), 17th century Portuguese nun who, purportedly, wrote the Letters of a Portuguese Nun (comprising five letters), that detailed her affair with French officer Noël Bouton (Marquis de Chamilly and, later, Marshal of France). In the story, the nun glimpsed the young officer only once from her window in 1641, while he was campaigning against the Spanish army in the Alentejo. She fell in love at once and wrote him five passionate letters. Although the Portuguese letters disappeared, they were "translated" into French and published in Brussels in 1669 (and later into several languages). The lyrical composition is full of absolute passion, hope, pleas and despair and were an instant literary success, resulting in the popularity of this style (coining the term portugaise becoming synonymous for "passionate love letter").

- Mário Beirão (poet)

- Pedro Caixinha, football manager currently with Cruz Azul

References

Notes

- Instituto Nacional de Estatística. Ine.pt. Retrieved on 2015-10-27.

- "Áreas das freguesias, concelhos, distritos e país". Archived from the original on 2018-11-05. Retrieved 2018-11-05.

- UMA POPULAÇÃO QUE SE URBANIZA, Uma avaliação recente – Cidades, 2004 Archived October 6, 2014, at the Wayback Machine Nuno Pires Soares, Instituto Geográfico Português (Geographic Institute of Portugal)

- Beja – PS conquista Câmara à CDU com maioria absoluta Archived December 13, 2013, at the Wayback Machine Diário de Notícias, October 2009. Retrieved June 2012

- La contribution de la prospection géomagnétique pour la compréhension de la paléoforme de Matabodes (Beja, Portugal) | António José Marques da Silva. Academia.edu (1970-01-01). Retrieved on 2015-10-27.

- "Beja, Portugal Köppen Climate Classification (Weatherbase)". Weatherbase. Retrieved 2019-04-20.

- "Nevão deixou a região de Beja branca". www.jn.pt (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2019-04-20.

- "Beja: Considerada o lugar mais quente de Portugal, Beja é uma cidade super grac". 2017-10-30. Archived from the original on 2017-10-30. Retrieved 2019-04-20.

- Costa, Rita Marques. "As cidades europeias estão mais quentes. Portugal está no fim da lista". PÚBLICO (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2019-04-20.

- Potes, Miguel Joaquim Fernandes (2008). "Climatologia e qualidade da água na Bacia Hidrográfica do Guadiana". dspace.uevora.pt. Retrieved 2019-04-20.

- "Monthly Averages for Beja, Portugal (1981-2010)". Instituto de Meteorologia. Retrieved 2014-08-10.

- Dias, Carlos. "Alentejo pode estar a caminho da pior seca de sempre". PÚBLICO (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2019-04-20.

- Manha, Correio da. "Mais de 5 mil com falta de água". www.cmjornal.pt (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2019-04-20.

- "Beja (08562) - WMO Weather Station". NOAA. Retrieved March 28, 2019.

- Diário da República. "Law nr. 11-A/2013, pages 552 24–25" (PDF) (in Portuguese). Retrieved 17 July 2014.

Sources

- The Rough Guide to Portugal (11 ed.), 1 March 2005, ISBN 1-84353-438-X

- Rentes de Carvalho, J. (1 August 1999), Portugal, um guia para amigos (in Dutch) (9 ed.), Amsterdam, Netherlands: Arbeiderspers, ISBN 90-295-3466-4

- Lefcourt, Charles R. (September 1976). "Did Guilleragues Write "The Portuguese Letters"?". Hispania. 59 (3): 493–497. doi:10.2307/340526. JSTOR 340526.

- Owen, Hilary (1997). "The Love Letters of Mariana Alcoforado". Cultura. 16 (14).

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Beja. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Beja. |

- Town Hall official website

- Museum Queen Eleanor (in Portuguese)

- Carmel of Beja (in Portuguese)