Behiç Erkin

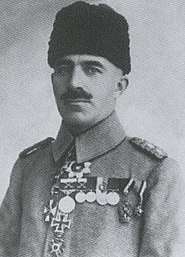

Behiç Erkin (1876 in Constantinople,[1] Ottoman Empire – November 11, 1961 in Istanbul, Turkey) was a Turkish career officer, first director (1920–1926) of the Turkish State Railways, nationalized under his auspices, statesman and diplomat of the Turkish Republic, who helped save almost 20,000 ethnic Jews in France during World War II. He was Minister of Public Works, 1926–1928, and deputy for three terms; and an ambassador. He served as Turkey's ambassador to Budapest between 1928–1939, and to Paris and Vichy between August 1939-August 1943. As Turkish ambassador in France under the German Occupation after June 1940, Erkin used the power of his office and nation's neutrality to save Jews who could document a Turkish connection, however slight, from the Holocaust.

Behiç Erkin | |

|---|---|

| |

| Ambassador of Turkey to France | |

| In office 1939–1943 | |

| President | İsmet İnönü |

| Ambassador of Turkey to Hungary | |

| In office 1928–1939 | |

| President | Mustafa Kemal Atatürk |

| Minister of Public Works | |

| In office January 14, 1926 – October 15, 1928 | |

| Prime Minister | İsmet İnönü |

| Preceded by | Süleyman Sırrı Gedikoğlu |

| Succeeded by | Recep Peker |

| Director General of the TCDD | |

| In office December 1, 1921 – January 11, 1926 | |

| Succeeded by | Vasfi Tuna |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Hakkı Behiç 1876 Constantinople, Ottoman Empire |

| Died | November 11, 1961 (aged 84–85) Istanbul, Turkey |

| Resting place | Eskişehir |

| Nationality | Turkish |

| Alma mater | Ottoman Military Academy, Ottoman Military College |

| Occupation | Army officer, director general, government minister, ambassador, politician |

| Awards | Iron Cross 1st Class (Germany) Medal of Independence (Turkey) |

| Military service | |

| Rank | Colonel |

| Battles/wars | World War I Turkish War of Independence |

Other Turkish diplomats in France and elsewhere, were also active in this rescue effort. The consulate staff under Necdet Kent in Marseille was particularly involved.[2][3]

Early life

Behiç Erkin was born as Hakkı Behiç in 1876 in Constantinople, Ottoman Empire.

Career

Starting in the early 1910s, Erkin was a close friend and early collaborator of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk.[4] Mustafa Kemal and Colonel Behiç Bey (Erkin) played crucial roles in the success of the battles at the Dardanelles front, where both men commanded during World War I. Erkin earned a high reputation and the German Iron Cross 1st Class military decoration, which served him when he needed to impress Germans during the Occupation. He also played a foremost part in the Turkish War of Independence. He took the family name "Erkin" after Turkey's 1934 Law on Family Names was passed. His surname "Erkin," which means "free man" was personally suggested by Atatürk in honor of his ability to make objective decisions in the face of outside pressure.

In 1939 then President İsmet İnönü hand-picked Erkin for the post of ambassador to France. Erkin's standing with the national government was critical to his mission of being able to save people from being dispatched to Nazi concentration camps in Eastern Europe. His decision to maintain the consulate in Paris even after the Occupation enabled his staff to keep closer watch and rescue Turkish Jews in the Paris area. In 1942-1943, Erkin personally arranged the evacuation across Europe to Turkey by rail of thousands of Turkish-associated Jews.

Mission in France

Background

According to a census French authorities conducted under German Army direction in autumn 1940, 3,381 of a total of 113,467 Jews over age 15, residing in Paris and holding French nationality, were of Turkish origin. The total number of ethnic Turkish Jews were estimated at five thousand people if those under 15 were counted. Scholars have estimated possibly ten thousand Jews of Turkish origin for the whole of France at the time.[5] Turkey's Code allowed for double nationality, but people had to update their registry at the consulate every five years to preserve a Turkish identity. Many former Turkish nationals in France had neglected this, as most had lived there for decades. Ties to their parents' country were often reduced to anecdotal level. Scholars estimate that approximately ten thousand Jews who solely held the Turkish nationality may have resided in France at the time.[6]

Erkin's tenure

Erkin arrived at the Turkish Embassy in Paris only three weeks before the start of the Second World War. While the embassy was small, its staff represented Turkey's administrative and cultural elite, all graduates of Galatasaray High School. They continued as leaders of Turkey in the postwar decades. Two among the staff, Fatin Rüştü Zorlu and Melih Esenbel, were later to become foreign ministers of Turkey. (Zorlu was executed after the 1960 coup d'état. A third colleague, Beşir Balcıoğlu, was assassinated in Madrid in 1978 by ASALA, Armenian militants, along with Zeki Kuneralp.) Namık Kemal Yolga, also known for rescuing Turkish Jews in Paris, became part of the embassy when he was appointed Vice Consul starting April 1940.

After the long phase of the Phony War (Drôle de guerre) and the occupation of southern France by the German Army, the consulate located in Marseille and headed by Necdet Kent was moved to Grenoble, Switzerland, which was a neutral nation. The coordination work was carried out by Leon Mandil, a Turkish Jew appointed a decade before by Atatürk as "special attaché". He had a perfect command of the French language and culture. His family had been prominent in Turkey since the 19th century.[7] >[8]

On 9 June 1940 Sunday, the French government moved in such haste to Vichy that it failed to notify all the embassies in Paris of the change of capital. It took one month for the Turks to move their embassy, with 20 staff members or spouses, but Erkin retained five men in Paris to run the consulate. Once in Vichy, Erkin had frequent contacts with virtually all Vichy officials, including Maréchal Philippe Pétain, Pierre Laval, Paul Baudoin, François Charles-Roux, Charles Rochat and members of embassies of other countries, including the United States. Following France's surrender to Germany, William D. Leahy represented the US as ambassador in Vichy only from December 1940 to May 1942.

In the early days, the Turkish embassy tried to protect ethnic Turkish Jews by encouraging them to post notices of Turkish nationality next to the "Jewish-owned enterprise" sign required by the Germans. The embassy tried to work with the Germans to protect their nationals. A letter of 28 February 1941 from the German embassy, signed Otto Abetz, stated that they would be "disposed to evaluate specific cases concerning Turkish nationals" as communicated by the consulate. But when Xavier Vallat was appointed Head Commissioner for Jewish Affairs, he gave new impetus to Vichy France's anti-Jewish actions.[9]

Through 1941-1942, measures against Jews in France became increasingly more severe. The Nazis gathered and deported the most recent Jewish immigrants, then those who had come to France after 1933, and then collected French Jews proper, those who had lived in France for generations. Vallat's office was concerned primarily with confiscating Jewish assets; he directed a wide-scale inventory to be drawn in June–July 1941.

Throughout 1942, Erkin assigned nominal trustees to protect enterprises owned by Turkish Jews. Near the end of the year, the Germans developed a scheme to transport all Jewish nationals of neutral countries to their respective home countries. Accordingly, on 19 September 1942, Berlin directed that Turkish Jews could be evacuated until 31 January 1943, a date later extended for two months and more. A few days before the communication, Erkin had secretly met with Germany's Consul General in Vichy Krug von Nidda, Otto Abetz, Heinz Röthke and Rudolf Schleier. He was ready to arrange the first train for Turkish evacuees, which departed from Paris in November 1942 to arrive in Edirne, Turkey eleven days later. It was decorated with a crescent and star. The enterprise was tense with danger, as the consulate was worried about potential attacks on the masses of Jews who gathered at the consulate. Erkin and his staff were able to transport thousands of ethnic Turkish Jews to safety.

Aged 67 in 1943 and having had his ambassadorial term extended three times, Erkin retired in August 1943 to return to İstanbul. In 1958 he completed his memoirs (published in 2010).

Behiç Erkin died on November 11, 1961. At his wish, he was buried in a courtyard near a railway junction in the Eskişehir train station, where he had started his career four decades before.

Biographical accounts

Erkin completed a 900-page memoir in 1958, published in 2010 by the Turkish Historical Society. His grandson used the memoir as the basis for his own research about his grandfather's life.[10] Erkin's memoirs dealt with his efforts to aid the Turkish Jews' in France, as their lives were increasingly at risk.

In 2007 Emir Kıvırcık, Erkin's grandson, published The Ambassador, an account of Erkin's tenure in France. The book was rich in details on conditions that prevailed in Vichy France. Kıvırcık related many individual stories while telling of his grandfather's efforts in the context of the Occupation. For example, he told of Robert Lazare Rousso, picked up by the Nazis in a random identity check in Paris on 13 December 1941 and dispatched to a camp. Under the number 3233, he was held with thousands of others for two months, before gaining release on 6 February 1942 due to pressure that Erkin's consulate brought with the Germans. As of 2007, Monsieur Rousso was still living in Paris. As another example, Herman Rothenberg and Isak Bitran were arrested in October 1942 and sent to Drancy internment camp. After the Turkish consulate corresponded for months with the SS about them, pleading for the release of neutral nationals, both were released on 12 March 1943. Three days later with their families, they boarded an evacuation train the embassy had arranged for emigration to Turkey.

In 2007 American actor and director George Clooney was considering a role as Erkin in a film project related to the ambassador's World War II years.[11]

In The Road to the Front (Cepheye Giden Yol) (2008), Kıvırcık covered his grandfather Erkin's World War I years.

Contrary to all these accounts, Turkish historian and newspaper columnist Ayşe Hür states in a column published in December 2007 that the efforts of Erkin in saving Turkish Jews have been greatly exaggerated. Quoting work by historian Corinna Guttstadt, the number of saved Jews is stated to be 114, not in the thousands as claimed by other biographies. Furthermore, according to the same article, the number of Jews that have been identified by the German authorities as possible Turkish citizens was 3036, so the number of people saved by Erkin appears to be a small fraction of the total.[12]

Yad Vashem application

In April 2007, an Israeli association of Jews with origins in Turkey applied to have Erkin included among the "Righteous Among the Nations" in Yad Vashem Holocaust Memorial.[13] The applicants, principally Israelis with origins in Turkey, are seeking witnesses to help document their application.[14]

See also

- Necdet Kent

- Namık Kemal Yolga

- Selahattin Ülkümen

- History of the Jews in Turkey

- Oskar Schindler

- Schindler's Ark (the book)

- Schindler's List (the film based on the book)

- Holocaust

- SS Kurtuluş

References

- Caroline Finkel, Osman's Dream, (Basic Books, 2005), 57; "The city's Byzantine name, rendered in Turkish as Konstantiniyye...","Istanbul was only adopted as the city's official name in 1930..".

- Naim Avigdor Güleryüz. "The Jewish Virtual History Tour". Turkey: Jewish Virtual Library.

- "Turkish diplomats honored in New York". Wallenberg Foundation. 1 November 2005.

- Andrew Mango (2002). Atatürk: The Biography of the Founder of Modern Turkey. The Overlook Press. ISBN 1-58567-334-X.

- Jacques Adler (1987). The Jews of Paris and the Final Solution. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-504306-5.

- Hans-Lukas Kieser (2006). Turkey beyond nationalism: towards post-nationalist identities. I.B. Tauris. p. 54. ISBN 978-1-84511-141-0.

- Leon Mandil's grandfather, Jak Mandil Pasha, was personal doctor to sultan Abdülhamid II. His younger sister Tilda Kemal (b. 1923, d. 2003) married novelist Yaşar Kemal.

- Another colorful character in Kıvırcık's book is Prodromos Stamatiades, nicknamed Bodo, who was Erkin's valet. He was an Anatolian Greek who had previously served Atatürk. Stamatiades became attached to Erkin in 1926, when Erkin was outgoing for a foreign mission, in order to avoid his being included in the Population exchange between Greece and Turkey.

- Michael R. Marrus, Robert O. Paxton (1987). Vichy France and the Jews - section "Vallat: An activist at work". Stanford University Press. p. 96. ISBN 0-8047-2499-7.

- Emin Çölaşan (16 February 2007). "Bir ibret belgesi ("An exemplary document")" (in Turkish). Hürriyet.

- "George Clooney considering Turkish project". Clooney Studio. 2007-01-22. Archived from the original on 2012-07-08.

- ‘Türk Schindleri’ efsaneleri by Ayşe Hür, Taraf, December 16, 2007 "Legend of the turk Schindler". Archived from the original on 2014-08-14. Retrieved 2014-08-14. (in Turkish)

- "L'ambassadeur de Turquie durant la Guerre postule à titre posthume au titre de Juste parmi les Nations ("The Ambassador of Turkey during the War is proposed for a posthumous title of the Righteous among the Nations")" (in French). Israel Valley Site Officiel de la Chambre de Commerce France Israël. 4 April 2007. Archived from the original on 2011-07-13. Retrieved 2007-12-27.

- "İsrailli Türkler kurtarıcıları için tanık arıyorlar ("The Turks of Israel seek witnesses for their savior")" (in Turkish). Haber 7. 2008-08-12. Archived from the original on 2011-03-07.

Films

- Turkish Passport (2011) www.theturkishpassport.com

- Desperate Hours (2005).

Further reading

- Behiç Erkin, Hâtırat 1876-1958, Ankara, TTK, 2010 (edited by Ali Birinci).

- Emir Kıvırcık, Büyükelçi (The Ambassador), Turkey: Goa Publications, 2007, (Turkish language), ISBN 978-9944-2-9102-6

- Stanford J. Shaw, Turkey and the Holocaust: Turkey's Role in Rescuing Turkish and European Jewry from Nazi Persecution, 1933-1945, New York: New York University Press; London, MacMillan Press, 1993

- Stanford J. Shaw, The Jews of the Ottoman Empire and the Turkish Republic, New York: New York University Press

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Behiç Erkin. |