Battle of Yenidje

The Battle of Yenidje, also transliterated as Yenice (Greek: Μάχη των Γιαννιτσών), was a major battle between Greek forces under Crown Prince Constantine and Ottoman forces under General Hasan Tahsin Pasha and took place between October 19–20 (O.S.), 1912 during the First Balkan War. The battle began when the Greek army attacked the Ottoman fortified position at Yenidje, which was the last line of defense for the city of Thessaloniki, which had a Greek majority population.

| Battle of Yenidje | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of First Balkan War | |||||||

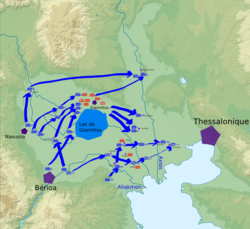

Map of the battle | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Crown Prince Constantine | General Tahsin Pasha | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| Thessaloniki Garrison | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 5 divisions | 25,000 men | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

188 killed 785 wounded |

250+ killed 1000+ wounded 200 captured 11-14 artillery pieces 2 flags | ||||||

Yenidje Location of the battle in present day Greece | |||||||

The rough and swampy terrain surrounding Yenidje significantly complicated the advance of the Greek army, most notably its artillery. In the early morning of 20 October, an infantry charge by the Greek 9th Evzone Battalion caused the Greek army to gain momentum, leading to the collapse of the entire western wing of the Ottomans. Ottoman morale plunged and the bulk of the defenders began fleeing two hours later. The Greek victory at Yenidje opened the way for the capture of Thessaloniki and the surrender of its garrison, helping shape the modern map of Greece.

Background

Following the conclusion of the Greek War of Independence, the Megali Idea (Great Idea) ideology came to dominate Greek foreign policy. The ultimate goal of the Megali Idea was the incorporation of all areas traditionally populated by Greeks into an independent Greek state.[1] The disastrous Greek defeat in the short Greco-Turkish War of 1897 exposed major flaws in the Greek Army's organization, training and logistics. Upon his appointment in December 1905, Georgios Theotokis became the first postwar Greek prime minister to focus his attention on strengthening the army. He established the National Defense Fund which financed the purchase of large quantities of ammunition. In addition a new table of organization was introduced for the country's navy and army, the latter being augmented by numerous artillery batteries. Theotokis' resignation in January 1909 and the perceived neglect of the armed forces by his successor resulted in the Goudi coup seven months later. Rather than taking power for themselves, the putschists invited Cretan politician Eleftherios Venizelos to rule the country.[2] Venizelos followed in Theotokis' footsteps by rearming and retraining the military, enacting extensive fortification and infrastructure works, purchasing new weapons, and recalling the reservists for training.[3]

The climax of this effort was the invitation in 1911 of a British naval mission and a French military mission.[3] The British mission was headed by Rear Admiral Lionel Grant Tufnell, who placed an emphasis on gunnery practice and fleet maneuvers, while his assistants introduced a new fuse for the Whitehead torpedo.[4] The French mission under Brigadier General Joseph Paul Eydoux focused its attention on improving discipline and training senior officers in large formation operations.[5] The Hellenic Military Academy was modeled after the École spéciale militaire de Saint-Cyr shifting its focus from artillery and engineer training towards that of infantry and cavalry.[6]

After being informed of a Serbo-Bulgarian alliance, Venizelos ordered his ambassador in Sofia to prepare a Greco-Bulgarian defense agreement by 14 April 1912. This was due to fears that should Greece fail to participate in a future war against the Ottomans it would be unable to capture the Greek majority areas of Macedonia. The treaty was signed on 15 July 1912, with the two countries agreeing to assist each other in case of a defensive war and to safeguard the rights of Christian populations in Ottoman-held Macedonia, thus joining the loose Balkan League alliance with Serbia, Montenegro and Bulgaria. Fearing a new war in the Balkans, the Ottomans mobilized their armed forces on 14 September and began transferring units to Thrace; the Balkan League responded in kind.[7] On 30 September, the League presented the Ottomans with a list of demands regarding the rights of its Christian population. The Ottoman Empire rebuffed the demands, recalled its ambassadors in Sofia, Belgrade and Athens and expelled the League's negotiators on 4 October. The League declared war against the Ottomans, while Montenegro had already began military operations on 25 September.[8]

Prelude

The Army of Thessaly crossed into Ottoman territory in the early morning hours of 5 October, finding most border posts to be abandoned. The first major clashes took place the following day when the 1st and 2nd Greek Divisions attacked Elassona, resulting in an Ottoman withdrawal towards Sarandaporo.[9] At 7 a.m. on 9 October, the Greek infantry began its assault on Sarandaporo. The 1st, 2nd and 3rd Divisions attacked the Ottoman main line frontally. In the meantime, the cavalry brigade and the 4th and 5th Divisions conducted a flanking maneuver from the west with the intention of striking the rear of the Ottoman positions.[10] The Konstantinopoulos Evzone detachment struck from the east of the pass. [10] Fearing that they would be encircled by the Konstantinopoulos Evzone detachment, the Ottomans began to withdraw at 7 p.m., towards their second defensive line at Hani 739, under the cover of the night. Upon reaching their second defensive line, the Ottomans became aware of the 4th Division's seizure of Porta Pass, panic spread in their ranks and many soldiers began fleeing and abandoning their equipment.[11] On the morning of 10 October, the 4th Division charged down the northern slope of the Rahovo Mountain, surprising the Ottoman infantry and artillerymen who engaged in a disorganized retreat.[12][13]

At 4 p.m. on 10 October, the 4th Division marched into Servia[12], while the Greek cavalry entered Kozani unopposed the following day.[14] On 13 October, the Greek army transferred its general headquarters to Kozani; a day later King George I arrived in the city, ordering the army to march towards Thessaloniki and Veroia.[15] The Ottomans fought a number of small scale delaying actions at Kolokouri, Tripotamos and Perdika, the Greek army nevertheless continued its advance taking Veroia and Katerini on 16 October. Between 17 and 18 October, the Greek general command forwarded its troops to the Veroia-Naousa plain. [16]

After their defeat at Sarandaporo, the Ottomans augmented the remnants of Hasan Tahsin Pasha's force with fresh reinforcements. Two divisions from east Macedonia, one reserve division from Asia Minor and one reserve division from Thessaloniki; bringing the total Ottoman forces in the area to 25,000 men and 36 artillery pieces.[17][18] The Ottomans chose to organize their main defensive line at Yenidje either because of the town's religious importance for Macedonia's Muslim population or because they did not wish to fight too close to Thessaloniki.[19] The Ottomans dug their trenches at a 130-meter (400 ft) high hill which overlooked the plain west of the town. The hill was surrounded by two rough streams, its southern approaches were covered by the swampy Giannitsa Lake while the slopes of Mount Paiko complicated any potential enveloping maneuver from the north.[18] On the eastern approaches to Yenidje, the Ottomans reinforced the garrisons guarding the bridges across the Loudias River, the rail line at Platy and Gida.[20]

On 18 October, the Greek general command ordered its troops forward despite receiving conflicting intelligence reports regarding the disposition of the enemy troops.[18] The 2nd and 3rd Greek Divisions marched along the same route towards Tsaousli and Tsekre respectively, both located north-east of Yenidje. The 1st Greek Division acted as the army's rearguard. The 4th Division headed towards Yenidje from the north-west, while the 6th Division circumvented the city further to west, intending to capture Nedir. The 7th Division and the cavalry brigade covered the right flank of the army by advancing towards Gida; while the Konstantinopoulos Evzone detachment was ordered to seize Trikala.[21]

Battle

The first shots were fired in the early morning of 19 October, the advance guards of the 2nd and 3rd Greek Divisions pushed back the Ottomans at Burgas. Upon reaching the bridge across Balitzas river, the two divisions became the target of heavy shelling from the hills surrounding Yenidje. The 4th and 6th Divisions likewise halted their advance, after being repulsed by massed rifle fire.[18] The Greek army command arrived at the battlefield at noon, in order to assess the situation and issue new orders. The 2nd and 3rd Divisions were to force their way across the bridge, conducting a frontal attack on the main body of the Ottoman forces behind it. The 4th and 6th Divisions conducted a flanking maneuver from the west, in the meantime the Konstantinopoulos Evzone detachment and the cavalry brigade rushed towards Loudias; thus creating two fronts on either side of the Giannitsa Lake.[22]

The Greek artillery's shelling was inaccurate since the ground was swampy and unstable. Only a single battery managed to establish itself at a distance of 4.5 kilometres (3 mi) from the Ottoman trenches. This caused the 2nd and 3rd Greek Divisions to significantly slow down their advance, however by nightfall, they managed to establish a large bridgehead across the Gramos river which flows into Giannitsa Lake from the north [18] Contrary to the orders they had received the 7th Division and the cavalry brigade encamped at Gida upon reaching it, while the Konstantinopoulos Evzone detachment likewise failed to cross the Loudias after failing to locate a bridge. The 4th and 6th Greek Divisions progressed steadily on the western edge of the battlefield, crushing two counter-attacks and forcing the Ottomans to move their headquarters further back.[23]

At 8 a.m., 20 October, an infantry charge by the 9th Evzone Battalion of the 4th Greek Division captured an Ottoman battery. The 4th Greek Division used the momentum it had gained to push back the entire western wing of the Ottomans. The 2nd and 3rd Greek Divisions made headway against their opponents, reaching the edge of Yenidje[24] and launching a bayonet attack on the Ottomans just as the 4th Greek Division arrived from the west. At 10 a.m., the Ottomans broke into a disorganized retreat, most fleeing towards Thessaloniki and Doiran.[25] The latter were detained by a Serbian cavalry unit that was advancing towards the Axios valley. Crown Prince Constantine ordered a single regiment of the 2nd Greek Division to chase the retreating Ottomans along the road to Thessaloniki, but it proved to be too narrow for an effective pursuit.[26]

At the same time a force of 3,000 Ottomans struck the 7th Greek Division at Gida, as it lingered in the area.[18] The Greeks held their ground and immediately went on the offensive, disobeying orders once again, they limited themselves to establishing a bridgehead at Kirtzalar instead of crossing the Axios. The Konstantinopoulos Evzone detachment managed to cross the Loudias by midday. However since the engineers of the 7th Division and the cavalry brigade failed to arrive on time, it was unable to reach the Axios and block its bridges; enabling many Ottomans to flee.[27]

Aftermath

Greek casualties in the battle of Yenidje numbered 188 killed and 785 wounded. The Ottomans lost over 250 killed, over 1,000 wounded, 200 men captured [28], two flags lost, 11 to 14 field artillery pieces captured and other significant material losses.[28][18] Following the capture of Yenidje, Crown Prince Constantine allowed the bulk of the Army of Thessaly to rest for three days after fifteen days of continuous fighting. Greek engineering units began repairing the bridges across the Axios that the Ottomans had previously destroyed.[29] In the meantime, the 5th Greek Division continued its march towards Monastiri until it was ambushed and defeated outside Sorovich on 21 October. The battle of Sorovich perplexed Constantine and made him hesitate just as the Greek majority city of Thessaloniki seemed to be within his grasp. Citing Greek intelligence agents within the Bulgarian capital that the latter had taken Serres and were rapidly approaching Thessaloniki, a vexed Venizelos repeatedly urged Constantine and King George I to act.[30] On 25 October, the Army of Thessaly finally crossed the Axios, reaching the Tekeli-Bathylakkos-Gourdino line.[31]

On the same day, Constantine received a delegation consisting of the ambassadors of the Great Powers to Thessaloniki and Ottoman general Sefik Pasha. Tahsin Pasha offered to surrender the city without a fight and in return requested that Thessaloniki's garrison could retain its weapons and retreat to Karaburnu where it was to remain until the end of the war. Constantine rejected the Ottoman appeal, demanding a complete disarmament of the Ottomans and offering to transport them to an Asia Minor port of their choosing. At 5 a.m. on 26 October, a second Ottoman delegation appealed for 5,000 weapons to be retained during the transportation, Constantine responded by giving the Ottomans a two hour ultimatum to submit to his conditions. At 11 a.m., the 7th Greek Division crossed Gallikos river, the last aquatic barrier before the city. Around the same time, Tahsin Pasha decided to given in to the Greek demands, dispatching messengers to alert Constantine about his intentions; the latter received the news at 2 p.m.[32]

The 7th Greek Division and two Evzone battalions were immediately ordered to seize the city; while Constantine sent a message to the commander of the Bulgarian division closest to Thessaloniki advising him to divert towards a direction where his troops would be more useful. At 11 p.m., Tahsin Pasha signed a document of surrender in the presence of officers Viktor Dousmanis and Ioannis Metaxas. Under the terms of the treaty Greece captured 26,000 men and seized 70 artillery pieces, 30 machine guns, 70,000 rifles and large amounts of ammunition and other military equipment.[33] Feigning ignorance of the fact that the Ottomans had already surrendered, the Bulgarian army continued to advance towards the city. Bulgarian general Georgi Todorov requested that the control of city be split between Bulgaria and Greece. Constantine refused, allowing only two Bulgarian battalions to rest within the city. The battle marked the capture of the city and its inclusion in the Greek state, helping shape the modern map of Greece. Nevertheless the Greek capture of Thessaloniki remained a significant point of tension with Bulgaria, ultimately contributing to the outbreak of the Second Balkan War.[34]

By May 1913, the numerically inferior Ottomans had suffered a series of serious defeats to the League's armies on all fronts. The League had captured most of the Ottoman Empire's European territories and was rapidly approaching Constantinople. On 30 May, the two sides signed the Treaty of London which granted the League's members all Ottoman lands west of Enos on the Aegean Sea and north of Midia on the Black Sea, as well as Crete. The fate of Albania and the Ottoman-held Aegean islands was to be determined by the Great Powers.[35]

Footnotes

- Klapsis 2009, pp. 127–131.

- Kargakos 2012, pp. 19–21.

- Katsikostas 2014, pp. 5–6.

- Hooton 2014, p. 65.

- Katsikostas 2014, p. 12.

- Veremis 1976, p. 115.

- Kargakos 2012, pp. 26–29.

- Kargakos 2012, pp. 35–38.

- Christopoulos & Bastias 1977, p. 290.

- Christopoulos & Bastias 1977, p. 291.

- Apostolidis 1913, pp. 203–205.

- Dimitracopoulos 1992, p. 44.

- Erickson 2003, pp. 218–219.

- Christopoulos & Bastias 1977, p. 292.

- Apostolidis 1913, pp. 241–243.

- Christopoulos & Bastias 1977, pp. 293–294.

- Kargakos 2012, pp. 79–81.

- Christopoulos & Bastias 1977, p. 295.

- Apostolidis 1913, p. 266.

- Kargakos 2012, p. 81.

- Kargakos 2012, pp. 81–82.

- Kargakos 2012, pp. 82–83.

- Kargakos 2012, pp. 83–84.

- Kargakos 2012, p. 84.

- Apostolidis 1913, p. 270.

- Kargakos 2012, p. 85.

- Kargakos 2012, pp. 85–86.

- Erickson 2003, p. 222.

- Christopoulos & Bastias 1977, pp. 295–296.

- Kargakos 2012, pp. 90–92, 66.

- Kargakos 2012, p. 94.

- Christopoulos & Bastias 1977, pp. 296–297.

- Christopoulos & Bastias 1977, p. 298.

- Kargakos 2012, pp. 99–101.

- Christopoulos & Bastias 1977, pp. 330–332.

References

- Apostolidis, Dimitrios (1913). Ο νικηφόρος ελληνοτουρκικός πόλεμος του 1912-1913 [The Victorious Greco-Turkish War of 1912-1913] (in Greek). I. Athens: Estia. Retrieved 13 November 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Christopoulos, Georgios; Bastias, Ioannis (1977). Ιστορία του Ελληνικού Εθνους: Νεώτερος Ελληνισμός απο το 1881 ως 1913 [History of the Greek Nation: Modern Greece from 1881 until 1913] (in Greek). XIV. Athens: Ekdotiki Athinon. ISBN 960-213-110-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dimitracopoulos, Anastasios (1992). The First Balkan War Through the Pages of Review L'Illustration. Athens: Hellenic Committee of Military History. OCLC 37043754.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Erickson, Edward (2003). Defeat in Detail: The Ottoman Army in the Balkans, 1912-1913. Westport: Praeger. ISBN 978-0-275-97888-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hooton, Edward (2014). Prelude to the First World War: The Balkan Wars 1912-1913. Stroud: Fonthill Media. ISBN 978-1781551806.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kargakos, Sarandos (2012). Η Ελλάς κατά τους Βαλκανικούς Πολέμους (1912-1913) [Greece in the Balkan Wars (1912-1913)] (in Greek). Athens: Peritechnon. ISBN 978-960-8411-26-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Katsikostas, Dimitrios (2014). "Η αναδιοργάνωση των ενόπλων δυνάμεων και το έργο της γαλλικής στρατιωτικής αποστολής Eydoux" [The Reorganization of the Armed Forces and the Efforts of the French Military Mission of Eydoux] (PDF) (in Greek). Hellenic Army History Directorate. Retrieved 13 November 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Klapsis, Antonis (2009). "Between the Hammer and the Anvil. The Cyprus Question and the Greek Foreign Policy from the Treaty of Lausanne to the 1931 Revolt". Modern Greek Studies Yearbook. 24: 127–140. Retrieved 9 April 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Veremis, Thanos (1976). "The Officer Corps in Greece (1912–1936)". Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies. Routledge. 2 (1): 113–133. ISSN 0307-0131.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)