Battle of Thannuris

The Battle of Thannuris (Tannuris) (or Battle of Mindouos[2]) was fought between the forces of the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire under Belisarius and Coutzes and the Persian Sasanian Empire under Xerxes in summer 528, near Dara in northern Mesopotamia. As they were trying to build a fortress in Mindouos, the Byzantines were defeated by the Sasanian army.[3] Belisarius managed to flee but the Sasanians destroyed the buildings. Despite their victory, the Persians suffered heavy losses, angering Kavadh I, the Sasanian king of Persia.

Background

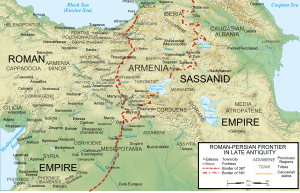

After the death of the emperor Justin I in 527, his successor Justinian I was determined to continue the war against the Sassanid Empire. He appointed Belisarius as magister militum of the East and put him in charge of strengthening the Byzantine positions and building a new fortress near Dara to protect the region from Persian raids. Thannuris appeared to be a convenient place for a city and a military force to be stationed but the current fort was vulnerable. He began firstly by overseeing the strengthening of the fortifications.[4]

Battle

At the same time, a Persian army under prince Xerxes with 30,000 men invaded Mesopotamia. Perceiving the threat, other Byzantine units and Ghassanid allies joined the forces of Belisarius to protect Roman workers undertaking the construction of the fort.

As the building operations were progressing, the Persian army rose up. Despite the Byzantine efforts, the Persians managed to close up to the walls and breach them.[5] Belisarius tried to counter-attack with his cavalry but was defeated and ordered to withdraw to Dara.

The exact course of the Persian campaign is poorly recorded in primary sources, which have often compressed the events of the battles of Thannuris and Mindouos into one. In the narrative that portrays them as separate battles, the battle of Thannuris took place before Mindouos, and is depicted as the Persians luring the Roman infantry into a trap where they fell into deep holes and were killed or captured.[6]

The end of the battle was disastrous for the Byzantine army. Belisarius and the cavalry escaped, but two commanders were killed and three captured.[7] Jabalah IV ibn al-Harith, ruler of the Ghassanids, who fought under Belisarius' command as a Byzantine vassal, fell from his horse and was killed by the Persians.[8] Coutzes's fate is uncertain. Procopius writes that he was taken prisoner and never seen again, while Zacharias of Mytilene records that he was killed.[9]

Aftermath

After the battle, the foundations of the new fortress were left in the hands of the Persians who then began to destroy them.[7] The Byzantine army retreated to Dara, but some of the infantry died of thirst on the march.[10]

Despite their victory, the Persians suffered heavy losses and then retreated behind the frontier. In particular, the loss of 500 Immortals from the Imperial Guard, made the king of Persia Kavadh I angry. Despite his victory, the general Xerxes was disgraced shortly after the battle by Kavadh I.[11]

The Byzantine emperor Justinian sent additional troops to reinforce the border fortresses of Amida, Constantia, Edessa, Sura and Beroea. He also raised a new army which was placed under the command of Pompeius, but a severe winter interrupted further operations until the end of the year.[7]

Belisarius would later be accused to incompetence because of this battle and the one later fought at Callinicum but all charges against him were cleared by an inquiry.[6]

According to Irfan Shahid, the Persians adopted the tactic of using trenches from the Hephthalites in the disastrous war of 484. Belisarius subsequently adopted it from the Persians and used it at the Battle of Dara two years later, and Muhammad also somehow adopted it from the Persians—possibly via the Ghassanid Arabs who saw their king killed at Thannuris—and used it at the Battle of the Ditch a hundred years later.[12]

Battle of Mindouos

It has been argued that the battle of Mindouos is a separate battle taking place shortly after the battle of Thannuris instead of being one event.[6]

See also

References

- Syvänne, Ilkka (2004). The Age of Hippotoxotai: Art of War in Roman Military Revival and Disaster (491-636). Tampere University Press. p. 460. ISBN 978-951-44-5918-4.

- Conor Whately, Battles and Generals: Combat, Culture, and Didacticism in Procopius, 2006, Netherlands, p.71 & 238

- Conor Whately, Battles and Generals: Combat, Culture, and Didacticism in Procopius, 2006, Netherlands, p.238

- Zachariah of Mitylene, Syriac Chronicle (1899). Book 9.

- Zachariah of Mitylene, Syriac Chronicle (1899). Book 9

- Hughes, Ian (Historian). Belisarius : the last Roman general. Barnsley. ISBN 9781473822979. OCLC 903161296.

- Bury 2015, p. 81.

- Greatrex, Geoffrey; Lieu, Samuel N. C. (2002). The Roman Eastern Frontier and the Persian Wars (Part II, 363–630 AD). London, United Kingdom: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-14687-9, p85.

- Martindale, John Robert; Jones, Arnold Hugh Martin; Morris, J., eds. (1992). The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire, Volume III: A.D. 527–641. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-20160-5.

- Zachariah of Mitylene, Syriac Chronicle (1899). Book 9

- Greatrex, Geoffrey; Lieu, Samuel N. C. (2002). The Roman Eastern Frontier and the Persian Wars (Part II, 363–630 AD). London, United Kingdom: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-14687-9.

- Shahid, Irfan (1995). Byzantium and the Arabs in the Sixth Century. Dumbarton Oaks. p. 78. ISBN 978-0-88402-214-5.

Sources

Bury, J. B. (2015). History of the Later Roman Empire, Vol. 1 of 2 : From the Death of Theodosius I to the Death of Justinian 395 to 565. Forgotten Books. ISBN 978-1330413098.