Battle of Dunbar (1650)

The Battle of Dunbar occurred on 3 September 1650, and is traditionally considered one of the major battles of the Third English Civil War, part of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms as the competing claims of the new Commonwealth of England and of Charles II to the throne of England were at stake. The English Parliamentarian forces under Oliver Cromwell defeated a Scottish army commanded by David Leslie which was loyal to Charles. Charles had been proclaimed King of 'Great Britain', France and Ireland by the Parliament of Scotland on 5 February 1649, five days after the execution of his father Charles I. Despite the defeat at Dunbar, the Anglo-Scottish conflict continued through 1651. During that period, Charles arrived in Scotland and was crowned as King of Scots at Scone. The battlefield of Dunbar has been inventoried and protected by Historic Scotland under the Historic Environment (Amendment) Act 2011.[4]

| Battle of Dunbar (1650) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Wars of the Three Kingdoms | |||||||

"Cromwell at Dunbar", by Andrew Carrick Gow | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

16,500 infantry[1] 5,500 cavalry[1] 9 guns Total: 22,000 9 guns |

7,500 infantry[2] 3,500 cavalry[2] Total: 11,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

800-3,000 killed[3] 10,000 prisoners[3] |

20 killed 58 wounded | ||||||

| Official name | Battle of Dunbar II | ||||||

| Designated | 21 March 2011 | ||||||

| Reference no. | BTL7 | ||||||

Background

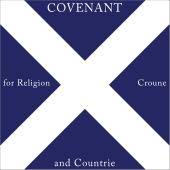

The Scottish and English parliaments had been allies against the Royalist supporters of Charles I during the First English Civil War and its extension into Scotland.[5] However, after the defeat of the Royalists and the capture of Charles I, differences in approaches to religion eventually came to the fore. Some among the Covenanters sought an agreement, or engagement, with the King as a way to achieve the implementation of Presbyterianism throughout Britain. The so-called Engagers invaded England in 1648 with the approval of the Scottish Parliament, and against the wishes of the Scottish Kirk, and were defeated by Cromwell's New Model Army at the Battle of Preston. After the defeat of the Engagers the opposing Kirk Party seized control of the government in Scotland, however, they realised that the English Parliament was never going to enact the Westminster Confession and that the only chance of Presbyterianism being instituted throughout Britain was through its acceptance by the King. Thus it was that on 23 June 1650 that Charles II landed in Scotland at Garmouth in Moray and by prior agreement, despite his Anglican and Roman Catholic sympathies, signed on his arrival the 1638 National Covenant and 1643 Solemn League and Covenant before being proclaimed King of Scots. This infuriated the English Parliament's Council of State who decided on a pre-emptive invasion of Scotland. Sir Thomas Fairfax, the Army's commander, disagreed with this strategy against the Scots Covenanters, who he saw as Protestant brethren, and resigned; his generalship being taken by Oliver Cromwell. John Lambert was made Sergeant Major General and appointed as the Army's second-in-command.

As Cromwell led his army over the border at Berwick-upon-Tweed in July 1650, the Scottish general, Sir David Leslie, continued his deliberate strategy of avoiding any direct confrontation with the enemy. His army was no longer formed of the battle-hardened veterans of the Thirty Years' War who had taken the field at the battles of Newburn and Marston Moor. Many of those had perished during the Civil War and the ill-fated 1648 invasion of England. Far more had left active service after the former event, some even leaving for Swedish or French service once more. This meant that a new army had to be raised and trained by the remaining veterans. It eventually comprised some 12,000 soldiers,[6] outnumbering the English army of 11,000 men.[2] Though the Scots were well-armed, the pressure of time meant they were poorly trained compared with their English counterparts, all of whom had served with Oliver Cromwell for years. Leslie chose, therefore, to barricade his troops behind strong defensive works around Edinburgh and refused to be drawn out to meet the English in battle. Furthermore, between Edinburgh and the border with England, Leslie adopted a scorched earth policy thus forcing Cromwell to obtain all of his supplies from England, most arriving by sea through the port at Dunbar.

Whether in a genuine attempt to avoid prolonging the conflict or whether because of the difficult circumstances he found himself in, Cromwell sought to persuade the Scots to accept the English point of view. Claiming that it was the King and the Scottish clergy who were his enemies rather than the Scottish people, he wrote to the General Assembly of the Kirk on 3 August famously pleading, "I beseech you, in the bowels of Christ, think it possible you may be mistaken." This plea, however, fell on deaf ears.

Battle

By early September, the English army, weakened by illness and demoralised by lack of success, began to withdraw towards its supply base at Dunbar. Leslie, believing that the English army was retreating, ordered his army to advance in pursuit. The Scots reached Dunbar first and Leslie positioned his troops on Doon Hill on the eastern edge of the Lammermuir Hills,[7] overlooking the town and the Berwick Road, which was Cromwell's land route back to England. Cromwell wrote to the governor of Newcastle: "We are upon an engagement very difficult. The enemy hath blocked up our way at the pass of Copperspath, through which we cannot get without almost a miracle. He lieth so upon the hills that we know not how to come that way without great difficulty; and our lying here daily consumeth our men, who fall sick beyond imagination."[8]

However, the Scots army, commissioned and funded by the Committee of Estates and Kirk representing the Scottish Parliament and the Church of Scotland,[9] manoeuvred itself into a new position, a move that turned out to be a major tactical blunder. Eager to curtail the mounting cost of the campaign, the ministers of the Kirk in attendance are said to have put Leslie under great pressure to press on with an attack. On 2 September 1650, he brought his army down from Doon Hill and approached the town, hoping to secure the road south over the Spott Burn in preparation for an attack on Cromwell's encampment. Witnessing Leslie's men wedge themselves between the deep ditch of the Spott Burn, and the slopes of the Lammermuirs behind them, Cromwell quickly realised that here was an opportunity for him to turn the tables on the Scots. He knew that an attack on the Scottish right flank would leave the left flank unengaged and that a successful push against the right would roll back the latter. On observing the Scots manoeuvring into their new positions, he is said to have exclaimed, perhaps referring to Joshua 10:8, "The Lord hath delivered them into our hands!"[10]

The Major-General [Lambert] and myself coming to the Earl of Roxburgh's House [Brocksmouth House], and observing this posture, I told him I thought it did give us an opportunity and advantage to attempt upon the Enemy. To which he immediately replied, That he had thought to have said the same thing to me. So that it pleased the Lord to set this apprehension upon both of our hearts, at the same instant. We called for Colonel Monk, and showed him the thing: and coming to our quarters at night, and demonstrating our apprehensions to some of the Colonels, they also cheerfully concurred.

— Cromwell.[11]

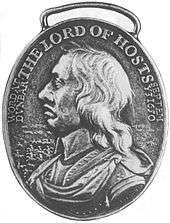

That night, under cover of darkness, Cromwell stealthily redeployed a large number of his troops to a position opposite the Scottish right flank. Just before dawn on 3 September, the English troops, shouting their battle cry "The Lord of Hosts!", launched a surprise frontal attack on the Scots, while Cromwell engaged their right flank. Soldiers in the English centre and on the right caught Leslie's men unawares but were held at bay by the long pikes of their Scottish opponents. The right flank of the Scots, however, with less freedom to manoeuvre, was pushed back under the weight of superior English numbers until its lines started to disintegrate. Cromwell's horse then clashed furiously with the Scottish cavalry and succeeded in scattering them. Observing this disaster, the rest of the Scottish army, hopelessly wedged between the Spott or Brox Burn and Doon Hill, lost heart, broke ranks and fled. Cromwell's secretary Rushworth wrote:

I never beheld a more terrible charge of foot than was given by our army, our foot alone making the Scots foot give ground for three-quarters of a mile together.

— Rushworth.[12]

In the rout that followed, the English cavalry drove the Scots army from the field in disorder.[13] Cromwell reported to Parliament that the "chase and execution" of the fleeing Scots had extended for eight miles.[14]

Cromwell claimed that 3,000 Scots were killed.[3] On the other hand, Sir James Balfour, a senior officer with the Scottish army, noted in his journal that there were "8 or 900 killed".[3] There is similar disagreement about the number of Scottish prisoners taken: Cromwell claimed that there were 10,000,(Cromwell said in his letter to Parliament that he had dismissed 5,000 men because they were Starved, sick or wounded. (Ref: Thomas Carlyle, Letters and speeches)[3] while the English Royalist leader, Sir Edward Walker put the number at 6,000, of which 1,000 sick and wounded men were quickly released.[3] The more conservative estimates of the Scottish casualties are borne out by the fact that the day after the battle, Leslie retreated to Stirling with some 4,000–5,000 of his remaining troops.[3]

Losses

- George Winram, Lord Liberton, Royalist, died of wounds 8 days after the battle

Aftermath

In his post-battle report to the Speaker of the English Parliament, Cromwell described the victory as "...one of the most signal mercies God hath done for England and His people...".[15] As a result of the destruction of the Scottish army, he was able to march unopposed to Edinburgh and quickly occupy it, although Edinburgh Castle held out until the end of December. The prisoners taken at Dunbar were force-marched south towards England to prevent any attempt to rescue them. The conditions on the march were so appalling that many died of starvation, illness or exhaustion. By 11 September, when the remnants arrived at Durham Cathedral where they were to be imprisoned, only 3,000 Scottish soldiers were still alive.[16] If Sir Edward Walker's statement is correct, that 6,000 prisoners were taken and 5,000 of them were marched south,[3] then 2,000 captives perished on the way to Durham. Of the estimated 5,000 Scottish soldiers that began the march southwards from Dunbar, over 3,500 died either on the march or during imprisonment in Durham Cathedral, more than the total number killed on the battlefield. In Arthur Heslerig's letter to Parliament on 2 October, he says that he received 3,000 prisoners at Durham and says that the prisoners had not been 'told' (counted) at Berwick. Of the 1,400 survivors, the majority were eventually transported as indentured labourers to English colonies in New England, Virginia and the Caribbean.[17]

In September 2015, archaeologists from the University of Durham announced that after 18 months work they had concluded that skeletons found in mass graves near Durham Cathedral were the remains of Scottish soldiers taken prisoner after the battle.[18] The bodies had first been discovered in 2013 during building work of a new café for the University's Palace Green Library, on the City's UNESCO World Heritage Site.[19] The archaeological evidence appeared to show that the bodies had been tipped into a mass grave with no signs of ceremony.[20]

References

- Trevor Royle – The War of the Three Kingdoms 2004, p. 68.

- Reid 2004, p. 64.

- Reid 2004, p. 81.

- Historic Scotland staff 2007.

- Weiss, Daniel (May–June 2017). "After the battle". Archaeology. 70 (3): 50–53. ISSN 0003-8113. Retrieved 9 July 2017 – via EBSCO's Master File Complete (subscription required)

- Reid 2004, p. 68.

- Reid 2004, p. 58.

- Buchan 1934, pp. 371–2.

- Plant 2007, The Committee of Estates.

- Carlyle 1904, p. 183.

- Carlyle 1904, p. 191.

- Buchan 1934, p. 378.

- Seymour 1979, p. 102.

- Carlyle 1904, p. 192.

- Carlyle 1904, p. 193.

- The Chapter of Durham, History.

- Butler 1896.

- Durham University (2 September 2015). "Skeletons found in mass graves are 17th Century Scottish soldiers". Durham University News. Durham University. Retrieved 18 July 2016.

- Durham University. "The Identification". Durham University Department of Archaeology. Durham University. Retrieved 18 July 2016.

- BBC News (2 September 2015). "Durham Palace Green remains were Scottish prisoners". BBC News. BBC. Retrieved 18 July 2016.

- Buchan, J (1934). Oliver Cromwell. London. pp. 371–2, 378.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Butler, James Davie (October 1896). "British Convicts Shipped to American Colonies". American Historical Review. 2 (1): 12–33. doi:10.2307/1833611. JSTOR 1833611.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Carlyle, T. (1904). Lomas, S. C. (ed.). The Letters And Speeches of Oliver Cromwell. 2. London. p. 102.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Inventory battlefields". Historic Scotland. 6 August 2007. Retrieved 1 April 2012.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Plant, David (25 February 2007). "The Committee of Estates". British Civil Wars and Commonwealth website. Retrieved 1 July 2012.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Reid, Stuart (2004). Dunbar 1650: Cromwell's Most Famous Victory. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-84176-774-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Seymour, W. (1979). Battles in Britain, 1066-1746. London: Sidgwick & Jackson Ltd. p. 145. ISBN 9780283985348.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- The Chapter of Durham. "Durham Cathedral History". Archived from the original on 21 December 2008. Retrieved 1 December 2008.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Unwin, Bruce (1 December 2011). "Durham Cathedral tribute to Dunbar". The Northern Echo.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Falkus, Christopher (1972). The life and times of Charles II. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

- Rogers, H.C.B. (1968). Battles and Generals of the Civil Wars. London: Seeley Service & Co.