Battle of Cassano (1705)

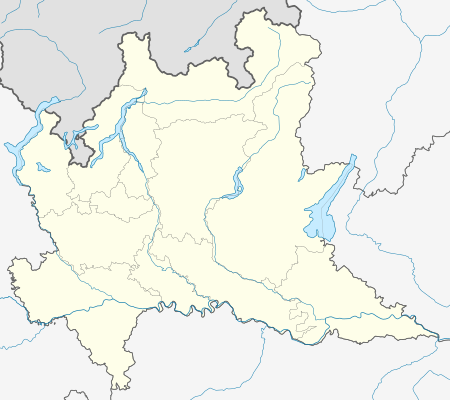

The Battle of Cassano took place at the town of Cassano d'Adda in Lombardy, Italy on 16 August 1705 during the War of the Spanish Succession between a French-led force commanded by the duc de Vendôme and an Imperial army under Prince Eugene of Savoy.[lower-alpha 1] It is generally considered a French tactical victory since the Imperial army was prevented from crossing the River Adda but casualties were heavy on both sides.

| Battle of Cassano | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of the Spanish Succession | |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

duc de Vendôme Philippe de Vendôme |

Prince Eugene of Savoy Leopold, Prince of Anhalt-Dessau | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 22,000 | 24,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 5,000 - 6,000 killed or captured | 2,500 killed or captured[1] | ||||||

Background

By 1705, the fighting in Northern Italy was in its fourth year, the French retaining the key strategic prize of Milan and generally having the upper hand. Finances were an enduring weakness of the Austrian Habsburg Monarchy with the Imperial army in Italy receiving minimal support from Emperor Leopold who was more focused on the Hungarian revolt known as Rákóczi's War of Independence.

In October 1703, Victor Amadeus II, Duke of Savoy voided his alliance with France and switched sides.[2] During 1704, Marshall La Feuillade captured Savoyard territories in Villefranche and the County of Savoy, a process which was completed when Nice surrendered in April 1705. Victor Amadeus now retained only his capital of Turin and parts of Southern Piedmont. The French commander in Italy, Vendôme, positioned his brother Philippe de Vendôme at Cassano d'Adda with 20,000 men while he himself led a mobile reserve.[3]

Prince Eugene of Savoy now resumed command in Italy while Leopold finally agreed to provide men and money; after his death in May, this commitment was maintained by his successor Emperor Joseph. The Maritime Powers [lower-alpha 2] signed an agreement with Prussia for a contingent of 8,000 led by Leopold, Prince of Anhalt-Dessau to join Prince Eugene's army.[4]

The Imperialists needed to relieve the pressure on Victor Amadeus to keep Savoy in the war; in May, Prince Eugene began marching along the right bank of the Adda looking for a place to cross, while Vendôme tracked him on the left bank, with a force of '20 squadrons of cavalry and 15 battalions of infantry.'[5] Since the nominal strength of a French squadron was 135 and 600 for an infantry battalion, this indicates a maximum of 2,700 cavalry and 9,000 infantry.[6]

When the Imperial army reached Iveza in the Brianza, they constructed a pontoon bridge under cover of artillery fire and Vendôme prepared to defend the crossing. This was a feint; after a perfunctory attempt to cross, Prince Eugene burned the bridge and headed towards Mantua. He then doubled back hoping to catch the French detachment at Cassano by surprise and arrived in Romanengo on 14 August, about 40 kilometres away.[7]

The battle

The Adda was deep and fast-flowing and generally unfordable, which limited potential crossing points, especially for large bodies of men. The town of Cassano is on the right bank, with a stone bridge protected by a small fortification or redoubt. The area was also divided by numerous small streams and irrigation channels, the most significant being the Retorto, an irrigation canal running parallel to the Adda. This was connected to the left bank by another bridge, also protected by a strongpoint.

Assuming Prince Eugene was heading for Mantua, Vendôme had ordered Philippe to leave Cassano and intercept him; they were preparing to move off when Prince Eugene began his assault around 2:00 pm on 16 August.

The French were in an extremely dangerous position, their baggage blocking the main bridge and the Adda behind them. Vendôme realised what was happening and joined his brother with 1,500 cavalry; he ordered the baggage train to be thrown into the river, formed a line along the canal and manned the bridge redoubts with his best troops. This included all five regiments of the Irish Brigade, four of which held the centre of the line; most contemporary accounts in English come from those connected to the Brigade.

After bitter fighting, the Imperialists captured the Retorto bridge giving them control of the sluice gates; these were now closed, lowering the water level in the canal by three feet and making it possible to walk across it. Prince Eugene ordered the Prince of Anhalt-Dessau and his Prussians into the canal to assault the French left; they managed to seize the further bank but suffered heavily in doing so. The battle surged back and forth across the river for several hours; contemporary accounts claimed 14,000 casualties on both sides, with 7,800 dead including nearly 1,000 French troops who drowned when forced off the bridge. Prince Eugene himself was wounded twice and had to leave the field; the fighting lasted between four and five hours until ended by sheer exhaustion with the opposing forces back at their starting positions.[8]

Aftermath

The two sides spent the next few weeks watching each other; Prince Eugene quickly recovered from his injuries and in early October began building barracks at Treviglio to make it seem he had decided to stay there for the winter. On 9 October, the Imperial army suddenly left camp and made a thrust towards Crema, trying to trap Vendôme against the river. This was a good example of Prince Eugene's ability to keep his opponents guessing but although Vendôme was only able to follow on 11 October, heavy rains brought the campaign to a close for the year. The French spent the winter around Castiglione and Mantua, with the Imperialists at Montichiari and Calcinato.

Opinion is divided on who won the battle; in 1708 Prince Eugene commissioned a series of paintings recording his 'victories' from Dutch artist Jan van Huchtenburg, one being Cassano.[9] Using the practice of the day, the Imperial army could technically claim victory as it remained in control of the battlefield at the end.

It is probably best described as a French tactical victory;[10] Prince Eugene relieved the pressure on Piedmont by occupying the main French field force for most of 1705 but was prevented from advancing further at Cassano. La Feuillade's force of 22,000 was not large enough to besiege Turin, giving Victor Amadeus time to reinforce it.

Footnotes

- 'Imperial' refers to the Holy Roman Empire, of which Austria was a part; the terms are often used interchangeably.

- England and the Dutch Republic

References

- The field of Mars: being an alphabetical digestion of the principal naval and military engagements, in Europe, Asia, Africa, and America, particularly ... century to the present period Volume 1 of 2 (2010 ed.). Gale ECCO. 1781. ISBN 0699108691.

- Falkner, James (2015). The War of the Spanish Succession 1701-1714 (Kindle ed.). 1302: Pen and Sword. ISBN 9781473872905.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Bancks, John (1745). The history of Francis-Eugene Prince of Savoy (2010 ed.). Gale ECCO. p. 77. ISBN 1170621236.

- Wilson, Peter (1998). German Armies: War and German Society, 1648-1806. Routledge. p. 120. ISBN 1857281063.

- O'Conor, Matthew (1845). Military History of the Irish Nation: Comprising a Memoir of the Irish Brigade in the Service of France; (2017 ed.). Forgotten Books. p. 299. ISBN 1330370775.

- Lynn, John (1999). The Wars of Louis XIV 1667-1714. Longman. p. 61. ISBN 0582056292.

- "A Brief Historical Sketch of the Irish Infantry Regiment of Dillon and the Irish Stuart Regiments in the Service of France, 1690–1791". Royal United Services Institution. Journal. 49 (325): 302–305. February 1905. doi:10.1080/03071840509418684.

- O'Conor, Matthew (1845). Military History of the Irish Nation: Comprising a Memoir of the Irish Brigade in the Service of France; (2017 ed.). Forgotten Books. pp. 301–310. ISBN 1330370775.

- "The Battle of Cassano, 1705". Retrieved 19 April 2018.

- Lynn, John (1999). The Wars of Louis XIV 1667-1714. Longman. p. 301. ISBN 0582056292.

Sources

- Bancks, John; The history of Francis-Eugene Prince of Savoy; (1745);

- Falkner, James; The War of the Spanish Succession 1701-1714; (Pen and Sword, 2015);

- Lynn, John; The Wars of Louis XIV, 1667-1714; (Longman, 1999);

- O'Conor, Matthew; A Military History of the Irish Nation: Comprising a Memoir of the Irish Brigade in the Service of France;

- Wilson, Peter; German Armies: War and German Society, 1648-1806; (Routledge, 1998);