Barred owl

The barred owl (Strix varia), also known as northern barred owl or, more informally, hoot owl, is a large species of owl. A member of the true owl family, Strigidae, they belong to the genus Strix, which is also the origin of the family’s name under Linnaean taxonomy.[2] Barred owls are brown to gray overall with dark striping on the underside contrasted immediately above that with similarly-dark and tight barring about their throat and nape.[3] Barred owls are largely native to eastern North America but have expanded their range to the west coast of North America, where they are considered invasive.[1][4][5] Mature forests are their preferred habitat, but they are also may be able to acclimate to various gradiants of open woodlands.[6] Their diet consists mainly of small mammals, but this species is an opportunistic predator and is known to prey upon other small vertebrates such as birds, reptiles, and amphibians as well as a variety of invertebrates.[7] Barred owls are typical for a member of the genera in terms of their nesting habits, tending to raise a relatively small brood often in a tree hollow or snag (but sometimes also in other nesting sites) deep in the woods.[8] By far the most controversial aspect of the barred owls current state is, upon their westward expansion, their encroachment of the range of their cousin, the threatened spotted owl (Strix occidentalis). Evidence shows the assorted threats posed by the invading barred species are only increasing. In turn, biologists have recommended culling operations to mitigate the deleterious effect of the barred on the spotted owl species.[9][10]

| Barred owl | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Strigiformes |

| Family: | Strigidae |

| Genus: | Strix |

| Species: | S. varia |

| Binomial name | |

| Strix varia Barton, 1799 | |

| Subspecies | |

| |

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Syrnium varium | |

Description

The barred owl is considered somewhat “subdued” and “drab” in coloration compared to the sometimes rich coloring of other sympatric owls.[11] Overall, this owl is greyish-brown or brown. The brownish color extends from the head to the back. Barred owls are scalloped with white bars on the mantle and the back, bearing as well some whitish spotting on the wing coverts.[8][6] The underside has a pale creamy gray-brown base color (ranging into dirty white in the palest individuals) overlaid about the throat and upper chest with horizontal, slightly crescent-shaped barring (hence its common name) while the belly is boldly streaked in a vertical pattern. The streaking is usually blackish or dusky brown or, sometimes, rufescent-brown.[3][11] The head is fairly large (although not especially so for a species in Strix) and rounded with no ear tufts.[12][13] The facial disc is pale grayish-brown with darker yet subtle concentric lines.[8] The bill is pale straw-yellow (occasionally showing a mild greenish tint) while the cere is “horn”-colored.[8][11] Its eyes are of a blackish-brown color, this being the only true owl of the eastern United States which has brown eyes; all others have yellow eyes.[14] The eyes may regularly appear intensely black in the field and, although large, are fairly closely set.[11] The barred owl has a well-developed eye anatomy. As is typical of owls, their ocular anatomy is quite distinct from diurnal raptors especially in terms of their photoreceptor cells, as they have a very large number of rod cells in their quite sensitive retina.[15][16] However, their pecten oculi is fairly smaller relative to the size of their large ocular globe (other large owls are known to have similar pecten proportions).[16] The vision in limited or almost no light during a laboratory study of a barred owl was found to be similar to that of other owls, including the long-eared owl (Asio otus) and the barn owl (Tyto alba).[17] The tarsi and toes are feathered up to the dark gray, black-tipped talons, but being more sparse and bristled in the southern races. On individuals of barred owls with bare sections of their toes, the toes are yellowish-gray in color.[8][18][19] The flight feathers are barred with whitish buff and brown while the tail is brown or grayish-brown with 4-5 whitish bars.[8] The mesoptile young of the barred owl are fluffy brownish-white with indistinct darker barring on head, back and mantle but quickly become juveniles which resemble adults but have less distinct markings (especially about the head and neck), more buff coloring overall, often some remnant down, pinkish skin and a pale blue green cere. Also the tail at this age may have as many as seven bands (though sometimes have four like adults). Full adult plumage is obtained via molt after about a year as well as adult bare part characteristics.[8][6][20] A study of tail molt in Washington showed that molt tends to occur relatively quickly and that young individuals are difficult to age by state of molt alone.[21] Southern barred owls tend to be darker and slightly smaller with less feathering on toes than northerly ones.[22] Rare captive and wild barred owl with albinism have been described and are pure white but tend to retain their brown eyes.[23]

The barred owl is a large species. The adult measures anywhere from 40 to 63 cm (16 to 25 in) in length while the wingspan may range from 96 to 125 cm (38 to 49 in).[24][25] The wing area (measured by square centimeter relative to the body mass) is quite intermediate amongst American owls, with the wing loading being lower than larger, but proportionately small-winged larger owls and even than some smaller owls but the barred has higher wing-loading than a number of smaller, often rather slenderly-build owls that have proportionately larger wings.[26] Wing-loading is related to hunting technique, with higher wing-loading owls typically hunting from a perch, with only a brief flight necessary to obtain food, whilst lower wing-loading owls often hunt their prey from active flight. Of these, barred and other Strix owls fall more so in the perch-hunting category.[12][26][27] As is the case in most owls, the various wing feathers of barred owls are uncharacteristic soft and bear a comb-like shape, which in turn renders their flight functionally silent during their hunts.[28] Like most birds of prey, the female is larger than the male barred owl, sometimes described as reverse sexual dimorphism (due to the fact that males average larger than females in most non-raptorial birds).[3] Among standard measurements, the wing chord of grown males varies from 303 to 340 mm (11.9 to 13.4 in), with an average from three sources of 326.2 mm (12.84 in), the tail may measure from 182 to 250 mm (7.2 to 9.8 in), with an average of 219.6 mm (8.65 in) and the culmen from the cere may measure from 22 to 27 mm (0.87 to 1.06 in), with an average of 24.3 mm (0.96 in).[25][29][30] Meanwhile for the female, the wing chord may range from 318 to 357 mm (12.5 to 14.1 in), averaging 335.8 mm (13.22 in), the tail from 204 to 257 mm (8.0 to 10.1 in), averaging 223.3 mm (8.79 in) and the culmen from the cere 20 to 30.7 mm (0.79 to 1.21 in), averaging 25.1 mm (0.99 in).[25][29][30] Sexual dimorphism is particularly pronounced in barred owls by body mass as males within a population are sometimes a third lighter in weight.[3][25] In the nominate subspecies (S. v. varia), average weights for males have been reported as 621.9 g (1.371 lb) (sample size 12), 632 g (1.393 lb) (sample size 20) and 681 g (1.501 lb) (sample size unknown) in three samples.[25][29][15] The weight range for adult males is known to vary from 468 to 812 g (1.032 to 1.790 lb).[25][29] The considerably larger female of the nominate subspecies has been reported to average 801 g (1.766 lb) (sample size 24), 872.6 g (1.924 lb) (sample size 14) and 909.5 g (2.005 lb) (sample size unknown).[25][29][15] Altogether, fully-grown female barred owls may weight from 610 to 1,150 g (1.34 to 2.54 lb).[25][29][15] In Baker Lake Basin in California (part of the “invasive” stretch of the range), 7 females weighed an average of 805 g (1.775 lb) while 8 males weighed an average of 663 g (1.462 lb).[31]

Confusion species

The barred owl is the only owl throughout the eastern part of the United States and most of the Midwest with its general characteristics: a large owl with a robust, rounded head and brown eyes, so confusion is unlikely in the core part of this species’ range. The great horned owl (Bubo virginianus) is larger and much heavier with prominent ear tufts, very different plumage coloring and pattern and yellow eyes.[8][14][15] The long-eared owl is much smaller and slimmer with differing markings, prominent ear-tufts and orangish eyes. In seldom cases, a very inexperienced person has mistaken the barred owl for these species, however.[8][14] On the fringes of its distribution (west, north and south), however, the barred owl may overlap slightly in range with other species from the Strix genus, which all share the same general form. A close cousin, the fulvous owl (Strix fulvescens) may range north into Mexico where the southernmost barred owls may persist, however so far as is known, their respective distributions are entirely and considerably allopatric. The fulvous owl is similar to a barred owl but is slightly smaller with richer, fulvous tones in plumage, cinnamon tail bands and a pale, plain facial disc without darker concentric lines.[3][25][32][33] Spotted owls, which now live alongside barred owls from southern British Columbia to northern California, are fairly similar looking as well but are too slightly smaller. In addition, spotted owls bear bold, dark spotting below, white spots about the head, neck and mantle instead of bars, a subtle cream brow on the facial disc and a darker, more richly brown, earthen tone overall.[3][15] The great grey owl (Strix nebulosa) is sympatric with barred owls from western Quebec to southeastern Alaska and share their range in many parts of the western United States as well as some of the northern Upper Midwest. The great grey species usually appears considerably larger than the barred owl (although there is considerable overlap in body mass) and much more solidly dark gray with a much larger, fairly bulbous head and relatively small yellow eyes.[3][15] The mottled owl (Ciccaba virgata) may or may not overlap with barred owls near the Mexico-Texas borderlands. The mottled can appear somewhat similar overall, with similar features and coloring. However, the mottled owl is rather smaller, with a darker facial disc (which in turn emphasize the white whiskers and brows) and has no bars on the upperbody. Younger mottled owls are somewhat rufous and much more richly and darkly colored than a barred owl.[6][32]

Vocalization

The barred owl is a powerful vocalist, with an array of calls that are considered “spectacular, loud and emphatic”.[34] Calls probably carry well over 0.8 km (0.50 mi).[35] Its usual call is a series of eight accented hoots ok-ok-ok-ok-ok-buhooh, or the “typical two-phrase hoot” with a downward pitch at the end.[3][36] The most common mnemonic device for remembering the call is "Who cooks for you, who cooks for you all."[8] Due to its best known call, the barred owl is sometimes colloquially referred to as Old Eight-Hooter.[37] At 80% of study posts in Virginia, barred owls responded to playback of this call.[38] A further call is the “ascending type” or the “legato” call, a series of variable notes ending in oo-aw or hoo-aah.[6][36] At least two other variations on the legato/ascending call are known.[36] 56% of studied owls in Virginia engaged in the ascending type call but 36% uttered only the closing notes.[38] The isolated hoo-aah, sometimes called the “inspection call”, was the most common song type in north Florida and the most likely to heard during daylight.[39] Several other calls, although some are not dissimilar variations on the main calls, are known.[38][40][41] Some of these vary into cackles, hoots, caws and gurgles, at times described as “sudden demonic laughter”, “cat-like screams” and “prolonged outbursts of cackling” and seem to be, amongst Strix species, an idiosyncrasy endemic to the barred owl.[8][34][42] Another call type is the “mumble”, a grumbling, slurred and subtle err-ERR-err, also a up-and-down “twitter” call at a high pitch.[36] When agitated, this species will make a buzzy, rasping hiss of about 3 three seconds every 10-30 seconds and click its beak together forcefully.[34] Females and juveniles beg with high scratching skreeechch notes.[3] The voice of the two sexes is similar but the female has a higher-pitched voice, with longer terminal notes.[39][43] 87-94% of calls are diagnosable to sex per one study.[36] While calls are most common at night, the birds do call during the day as well, especially when provoked by human playback or imitation.[44] They are more responsive than any hawk in the east to playback of calls of their own species.[45] The barred owl is noisy in most seasons but peak vocalization times for barred owls tend to be between late January (i.e. Florida) and early April (i.e. Canada).[39][46][47] Two seasonal peaks in vocalizations, one right before breeding and another after the young have dispersed, was detected in Connecticut with peak vocalizations on nights with extensive cloud cover.[48] Peak times for vocalizations are between 6:00 PM and 6:00 AM, with the least frequent vocalizations around mid-afternoon.[39] There seems to be no evidence of regional variation in song types, or dialects, in different regions of the southeastern United States (from east Texas to south Florida to North Carolina), likely due to extensive introgression while individual variation, recent signal evolution and local adaptations may also play a part.[49] 84-87.5% of recorded calls can be used distinguish individuals, via the review of spectrograms.[50]

Distribution and habitat

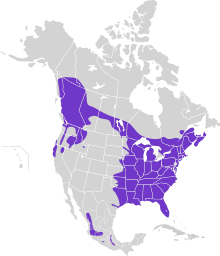

The barred owl is distributed throughout most of the eastern United States, as well as much of southern Canada.[3] They are found as far northeast as much of Nova Scotia (western two-third), New Brunswick and Sept-Îles, in much of Quebec, up to Lake Mistassini, and Ontario, up to Moosonee.[1][51][52][53][54] The barred owl has been recorded as ended up as far north as central Labrador, though the species is not yet confirmed to breed in the province.[55] The barred owl ranges in every part of the eastern United States continuously from northernmost Maine down throughout New England, the Mid-Atlantic states, much of the Midwest, the Southeast United States and all of Florida.[1][15] They are found to as far east without substantial gaps to the limits of western Minnesota, easternmost South Dakota, the southeastern corner of Nebraska, the eastern half roughly of Kansas, most of Oklahoma and east Texas to as far west as Cisco and Burnet.[1][56][57][58][59] Arguably and discontinuously from Texas, the species may range into central and southern Mexico but these populations are now often considered a separate species.[1][60] These initial parts of the range in the eastern and central stretches would be considered as where the species is “native”.[6][61] A wandering barred owl was once seen flying over Lake Michigan 48 km (30 mi) from the nearest land.[62]

Range expansions

The remaining parts of the range are considered where the barred owl introduced itself in the last century or so.[61][63] The historical lack of trees in the Great Plains presumably acted as a barrier to the range expansion, and recent increases in forests broke down this barrier.[61][63] Increases in forest distribution along the Missouri River and its tributaries provided barred owls with sufficient foraging habitat, protection from the weather, and concealment from avian predators to allow barred owls to move westward, initially along other forested river corridors (i.e. the Yellowstone and Musselshell). Decades later, increases in forests in the northern Great Plains allowed them to connect their eastern and western distributions across southern Canada.[63] These increases in forests were caused by European-American settlers via wildfire suppression as well as ceasing the fires historically set by Native Americans, and by increased tree-planting.[63][64] To a lesser degree this regional net forest increase was also caused by these settlers' extirpating American bison (Bison bison) and by overhunting elk (Cervus canadensis), deer (Odocoileus spp.) and, in some areas, by extirpating North American beaver (Castor canadensis) and replacing native ungulates with livestock.[63] Increase in trees in the Great Plains is considered a main cause of the range expansions of many other species of birds[65] including western kingbird (Tyrannus verticalis),[66][67] eastern phoebe (Sayornis phoebe),[68] eastern bluebird (Sialia sialis),[69] blue jay (Cyanocitta cristata),[70][71] brown thrasher (Toxostoma rufum),[72] red-tailed hawk (Buteo jamaicensis),[73] and American crow (Corvus brachyrhynchus).[74]

Back in Canada, the Barred owls with range expansion now range through southern Manitoba (but for the southwest corner), a broad section of south-central Saskatchewan and east-central and nearly all of western Alberta, now up to High Level.[1][8][75][76][77][78] The barred owl has been present in Manitoba at least since 1886, Alberta since 1932 and in Saskatchewan since 1948.[79][80][81] However, a study in Alberta has shown that barred owls have likely been present for no less than 100 years.[82] This owl species currently ranges through much of British Columbia, where they have been expanding their range since at least 1943, including Vancouver Island and as far north as Fort St. John.[83][84][85] The barred owl has had a further northward expansion in the west to southeastern Alaska (i.e. Skagway to Ketchikan) and extreme southwestern Yukon. To date, the IUCN has not updated its species range map for the barred owl to reflect these new northerly records.[1][33][86] In the western United States they also range into northwestern Montana and northern Idaho.[87][88] Barred owls were first verified in southwest Montana in 1909 and in northwest Montana in 1921 (although reports of the species may date back to the 1870s) but not in Idaho until 1968.[61][64] Of unknown origin, Barred owls have been seen in Colorado since around the turn of the 20th century.[89][90] They range broadly in eastern and western Washington (reached by 1965) and western Oregon (reached by 1972) (mostly along the forested corridors hugging the montane areas of the Cascade, Olympic and Blue ranges), and northern California (reached by 1976), now down to the Redwood National Forest, the Sierra Nevadas and outer San Francisco.[91][92][93][94][95][96][97][98]

Habitat

The habitat used by barred owl is largely old deciduous, mixed forests and, occasionally, coniferous forests.[3] Old growth forests are preferred due to more extensive potential nest sites, less lower branch density to impede hunting (and perhaps superior structural complexity to aid hunting), greater security from mobbing and perhaps greater thermoregulation.[99][100][101][102] They are often found in bottomland hardwood forests in the largest swath of the native breeding range, often (particularly from Virginia south and west) with deep, dark stands of oak, gum and cypress.[8][103] Secondary habitat, often used during foraging forays, in the south are often oak savanna or cabbage-palm (Sabal palmetto) areas.[8] Regardless of area, some variety of water is frequently present, including riparian areas or swampy ground.[3][34][104] Closed canopy forests were preferred in a study from Oklahoma (62.8% of habitat used), followed by fallow agricultural fields (10.6%), wetlands (8.1%) and open terrain (6.2%). The latter three were visited during hunting forays and wetlands and open terrain areas were not used outside of the breeding season.[105] Along the Atlantic coast area from New England to New Jersey, barred owls are often found in mixed swamps areas with cedars, seldom wandering to adjacent wetlands or farmland.[106][107] The species may be at home in wooded areas in mountainous regions.[3] More upland wooded habitats, often in mixed woods containing hemlock, alder, poplar, pine and oak, are typical in the northern part of the range.[11][104] A study in northern New Jersey found at least 15 tree species of both conifer and deciduous trees were routinely used for differing purposes.[108] In Michigan, barred owl habitat usually consists largely of some combination of hemlock and maple trees, with mixed forest usage being use disproportionately to its prevalence in the environment.[109] Large oak stands were preferred in Minnesota, a bit ahead of mixed forest and far ahead of white cedar (Thuja occidentalis) swamps and other habitat types, which were either too dense, too open or had too few attractive nesting sites.[99][110]

Barred owls are not confined to extensive forest, also dwelling extensively in semi-open wooded areas, locally in large parks with mature trees and in forest adjacent regions recently logged.[3] Recent studies show suburban neighborhoods can be ideal habitat for barred owls and the species may be considered a local synanthrope.[111] Using transmitters, scientists found that some regional populations, such as in Charlotte, North Carolina, increased faster in the suburban settings than in old growth forest. A factor of this suburban success may be easily accessible rodent prey in such settings. However, for breeding and roosting needs, this species needs at least some large trees and can be locally absent in some urban areas for this reason. The increased offspring offset the death rate due to impacts from cars, other types of collisions and disease.[112] Similarly, in Piedmont, South Carolina, productivity of the owls was higher in suburban areas and they comprised 41% of the territories of the local owls but various sorts of anthropogenic mortality were seemingly higher.[113] In suburban areas of Ohio barred owls 41.4% of range was forested, 29.8% was low-density residential areas and pasture less than 15%.[114] On the other hand, studies from the Northeastern United States, such as in New Jersey, found barred owls breeding mainly in plots of old-growth woodlands, and rarely successfully breeding in peri-urban areas, in part because of competitive and predatory displacement by great horned owls.[104][115] Furthermore, a study in North Carolina showed most studied barred owls appear to usually favor areas with at least 86 to 370 ha (210 to 910 acres) on wooded areas but did not seem to be effected by the presence of roadways.[116]

In the Pacific Northwest, they can quite adaptive to secondary forests.[6] On the other hand, in Ontario where the barred owl is “native”, secondary forest seemed to be largely avoided per a study.[117] In the recent western part of the range, barred owls often dwell in mixed wood areas, often where there are lowland stands of balsam poplar (Populus balsamifera), trembling aspen (Populus tremuloides) and white spruce (Picea glauca), occasionally but not commonly in pure conifer boreal stands.[101][118][119][120] Barred owls in California preferred stands of red alder (Alnus rubra) and appeared to avoid areas with higher densities of Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) and tanoak (Notholithocarpus densiflorus).[121] More so confined to inland areas, i.e. eastern Washington, Idaho, Manitoba and Montana, they prefer Douglas fir, ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa), paper birch (Betula papyrifera), burr oak (Quercus macrocarpa) and western larch (Larix occidentalis).[122][123][124][125][126] In north-central Alberta, the use of old growth forest was far more prevalent than its occurrence in the wild.[127] In the Cascades Range of Washington, barred owls usually dwelled in areas with more grand firs (Abies grandis), taller and more diverse tree heights, more enclosed canopies, with higher numbers of trees per acre and less ground cover.[128] In Saskatchewan, barred owls preferred areas with a minimum of 66% forest cover.[129]

Taxonomy

_(5957075195).jpg)

The barred owl was first decreased by Benjamin Smith Barton, a Philadelphia physician as well as scientist and naturalist, in 1799, so named due to the varied directions the dusky markings take on their underside.[130] The barred owl is a member of the wood-owl genus Strix, part of the typical owl family Strigidae, which contains all species of owl other than the barn owls. Conservatively, about 18 species are currently represented in this Strix genus, typically being medium to large sized owls, characteristically round-headed and lacking ear tufts, which acclimate to living in forested parts of various climatic zones.[13][131] Four owls native to the neotropics are sometimes additionally included with the Strix genus though some authors include these in a separate but related genus, Ciccaba.[132][133] Despite the diversity of Strix species in the Americas, genetic and fossil evidence indicates that the genus originated in Eurasia.[133][134][135] Some authors considered that the barred owl was derived from or even conspecific with the Ural owl (Strix uralensis) although it is unlikely that there was ever a continuous population between eastern Asia and the North America Strix populations due to their requirement for mature forests (and there is much that separates the Ural species from barred owls in form, markings, voice and some aspects of ecology).[6][136] It should not be ruled out however, that the Ural owl and its more numerous and well-known cousin, the tawny owl (Strix aluco), share a common ancestor with the American quadrant of northerly Strix species, with a divergence point no more recent than the early Pleistocene era.[8] The barred owl is roughly intermediate in size between the larger Ural and the smaller tawny owl, but the structural features of its relatively short and decurved claws more so resemble the tawny species as does their dietary and habitat ecology.[8] The spotted owl has been hypothesized to be within a superspecies with the barred owl.[137] However, genetic testing reveals very early divergence (likely at or near their ancestor’s entry to North America) between spotted and barred owls.[138] A fossil species once called Strix brea from the early Pleistocene in California does little to resolve the ancestry of modern species given its ambiguous relation to any living Strix. The fossil species was larger (more similar in size and slenderness to the great grey owl albeit slightly smaller skulled and geographically isolated from that species) and longer-legged than either the spotted and barred owls, and is now considered to be in a separate genus, Oraristrix.[139][140] Pleistocene era fossils of probable barred owls are known from Florida, Tennessee and Ontario.[141][142][143] Despite being previously considered cousins of the barred owl, there is much uncertainty about the relations of three neotropical species of Strix: the rusty-barred owl (Strix hylophila), the rufous-legged owl (Strix rufipes) and the Chaco owl (Strix chacoensis), and based on voice and distribution it seems improbable that they’d be closely related to the barred owl.[12][144]

Ambiguities continue as to the relation of barred owls to two Mexican and Central American owls that are clearly very similar to the barred species. One is the fulvous owl, which has been often considered conspecific and the other is the cinereous owl (Strix sartorii) which until very recently been considered a barred owl subspecies.[3][8][6][33] The fulvous owl is considerably geographically isolated from any barred owl population and moreover has a quite different voice.[145][146] The cinereous owl is more similar in plumage to a barred owl, albeit with cooler, less brown coloring, darker, bolder streaking and a typically paler facial disc. The cinereous species’ song resembles a more sonorous, deeper version of the fulvous owl song and, in both species, the song is quite different from that of the barred owl.[147] While the fulvous is a slightly smaller owl (averaging up to 20% smaller than northern barred owls) than the barred, the cinereous seems to be the second largest American species of Strix (after the great grey owl) and is a larger (estimated mean weights of the two sexes 878 and 1,113 g (1.936 and 2.454 lb), respectively) and appreciably larger footed predator than the barred owl.[148][149] A genetic study utilizing haplotypes showed that the cinereous owl is extremely divergent from the barred owl, puzzlingly with a more pronounced genetic distance from the barred than the more separated and southerly fulvous owl. The fulvous bore a 4.5% mean genetic distance from the barred species. In summation, the authors strongly advocated that each the barred, fulvous and cinereous be treated as separate species.[148] The fulvous owl is usually considered distinct in modern accounts while the cinereous is recognized by the International Ornithologists' Union but not by the American Ornithological Society.[148][150]

Subspecies

_(9732594639).jpg)

The subspecies of the barred owl vary mostly by region, with slight to moderate variation by coloring, size and extent of feathering on the toes. Although several have been described in the past, the barred owl may include only three subspecies, subsequent to the separation of the fulvous and cinereous forms.[33][25][151]

.jpg)

- S. v. varia (Barton, 1799)- The northern barred owl. This race lives throughout the Northeastern United States and the Upper Midwest, ranging far as south as Oklahoma, the Carolinas and northern Georgia. It is also considered to comprise all western “invader” birds found as far west as California and British Columbia.[3][6] However, genetic study of westerly birds show a substantial isolation, possibly up to the subspecific level, of the western and eastern populations of the northern owls, with an estimated divergence of around 7,000 years, perhaps indicating an unknown history of the species in remote forests of northern and central Canada (far west of what was considered their original distribution) that radiated more recently to comprise the western populations.[152] This race is generally the typical mid gray-brown variety of barred owl.[3] However, a paler variation with very washed out markings and a more pure whitish base color is known (in eastern Canada such as Quebec), formerly considered a race S. v. albescens, as well as darker and browner variation in northern Minnesota (formerly S. v. brunnescens).[6][153] This race is fairly large (the largest race on average with the probable separation of the cinereous owl) but can show considerable regional size variation.[154] The wing chord and tail length may measure from 312 to 340 mm (12.3 to 13.4 in) and 215 to 230 mm (8.5 to 9.1 in) in males and 320 to 352 mm (12.6 to 13.9 in) and 224 to 257 mm (8.8 to 10.1 in) in females.[3][25][154] One nominate bird had a tarsus length of 63.5 mm (2.50 in) and the culmen from the cere may measure 23.5 to 30 mm (0.93 to 1.18 in).[154] Most known published weights, including the lightest and heaviest known barred owls, have been recorded for the northern barred owl subspecies.[3][25][154]

- S. v. georgica (Latham, 1801)- The southern barred owl or, alternately, the Florida barred owl. This subspecies is found in southern North Carolina closer to the coast along to broadly through Georgia and all of Florida.[6][25][155] A form called S. v. sablei, from the isle of Sanibel, Florida, is not well-described and probably not distinct.[156] This race is similar to the nominate northern subspecies but averages a slightly darker and warmer brown on the back as well as about the underside barring and streaking. However, it differs from the nominate most strongly by its mostly bare toes. Although the race is slightly smaller on average than the nominate subspecies, the average difference is only about 3%. Nonetheless, this is still the smallest of the three subspecies on average.[3][6] Known wing chord lengths can vary from 315 to 357 mm (12.4 to 14.1 in). Tail length is 205 to 231 mm (8.1 to 9.1 in) and the bill from the cere is 23 to 28 mm (0.91 to 1.10 in).[3][6][154] Males in Florida were found to weigh from 681 to 800 g (1.501 to 1.764 lb), with averages in two samples of 718 and 744 g (1.583 and 1.640 lb), while two females weighed 850 and 875 g (1.874 and 1.929 lb), respectively. It therefore appears to show less pronounced sexual dimorphism than the northern barred owl race.[15]

- S. v. helveola (Bangs, 1899)- The Texas barred owl. Comprises most barred owls found in Texas (although any owls from north Texas are from the nominate subspecies).[3] The distributional range is considered to range as far north as Lee county, east to Chambers county, west to Kerr county and south to Nueces county but some records show they range down to adjacent lowlands of Mexico.[3][6][32][157] In this race, the ground coloration tends to pale gingery-cream and the back and head tend to be a pale brown ranging into an almost cinnamon color.[6] The toes can vary from rather bare to slightly bristled.[3] This race is similar to other barred owls in size, perhaps averaging marginally smaller than those in the nominate race, but its bill and feet are larger on average than the preceding two races.[6][25] The wing chord measures 330 to 355 mm (13.0 to 14.0 in) while the tail may measure 210 to 254 mm (8.3 to 10.0 in) and the culmen from the cere around 28 mm (1.1 in).[154]

Behavior

.jpg)

The barred owl like most owls is largely adapted to nocturnality.[3] Between 5:00 am and 8:00 pm, juvenile barred owls were recorded to sleep an average of 28% of each hour.[158] Peak times in Minnesota were found to be right after sunset and just before dawn.[159] Nonetheless, they are not as fully nocturnal as many owls and rank around 6th amongst 19 regular North American owl species for the regularity of their activity outside of nightfall, especially in particular circumstances such as when a rival or a human impersonator is emitting barred owls calls or whilst hunting. Often daytime activity tends to be early in the morning or around dusk but potentially at any time (overcast days being preferred).[160][161][162][163] In Juneau, Alaska, the barred owl when compared in a study to other owl species was considered “non-linear” in activity, with the peak discernable recorded activity time based on vocalization being right at sunset rather than after it.[164] This species often spends the daytime hidden away in dense foliage of a tree, often at minimum 5 m (16 ft) above the ground, but sometimes also roosts in branch close to a broad trunk or in a natural tree hollow.[3][8] Roost tree heights in Minnesota was typically 8 to 12 m (26 to 39 ft) while, in Illinois, they were up to 9 m (30 ft).[165][166] Recent fledged owls sometimes roost in tall grass, usually after falling from the nest tree.[46] Roost site selection may be partially dictated by thermoregulation, as in spotted owls, with shadier roosts likely to mitigate heat stress.[167] They seldom rely on camouflage, instead often flying at the least disturbance and not allowing close approaches, making them potential difficult to observe.[11] Yet, on the other hand, they can be surprisingly tame and seemingly curious of people in the wild; further they are considered “as mild and engaging” as a predator can be.[11] Barred owls are regularly subject to mobbing by small birds, from several small passerines to corvids and woodpeckers, and mammals when discovered by them during the daytime, and such situations may lead to them being attacked by diurnal birds of prey.[3][34][168] There are some records of barred owls engaging in allopreening, presumably between pairs, with each other in the wild.[169][170] They are skilled and silent fliers and frequently use routine forest flyways with open understory and low branch densities.[99]

Like most species of owl in the Strix genus, the barred owl tends to be highly territorial regardless of the time of year.[3][100][45][99] The territories are claimed by singing from different perches, often near the perimeter of its perceived home range. The boundaries are almost always well-maintained by barred owls and are generally stable from year to year and even generation to generation.[99] Territory sizes have been determined via radiotelemetry.[3] The average territory size of 13 in Minnesota was 273 ha (670 acres), of 7 in Michigan it was 282 ha (700 acres) and of 10 in Wisconsin was 337.9 ha (835 acres).[101][127][99] Another Minnesota study found pairs to occupy a mean of about 226 ha (560 acres) in mixed hardwood-conifer woods.[3] Pairs in an Oklahoma study were reportedly found every 110 to 165 ha (270 to 410 acres).[105] The mean territory size from 10 studies were estimated from throughout the range. In this study, the breeding season mean area was calculated at 256.7 ha (634 acres) in males and 297.8 ha (736 acres) in females; whereas the means in nonbreeding season were 900.4 ha (2,225 acres) in males and 536.2 ha (1,325 acres) in females. Overall, the annual mean home range for males was 782 ha (1,930 acres) and for females was 538.7 ha (1,331 acres).[171] The breeding range’s mean home size in Washington was 321 ha (790 acres), while it was 971 ha (2,400 acres) in the non-breeding season.[101] When territorial boundaries move, it is often correlated to reduced food supplies.[101][172] The ranges of pairs overlaps in the breeding season, at 87-95% range overlap, but decreases down to 45% after hatching.[173] In a Florida study of barred owls, territorial responses, including several duets, by a pair were found to be provoked by researchers playing calls of both “stranger” owls and recordings of owls that were neighbors to the pair being tested.[174] The aggressive response even to known neighbors in this study is unusual.[174] In tawny owls in a study from Italy, for instance, they responded mildly or not at all to the calls of neighboring tawny owls known to them but with great aggression to the calls of “stranger” owls.[175] Due to its rather stolidly territorial nature, the barred owl is not normally a migratory species.[3] Claims in the past of “rather impressive” flights in New England in the past were lacking in verifiable details.[8] Of 158 banded recoveries in the northern part of the range, movements during winter were found to cover no further than 10 km (6.2 mi), while all those recovered in Saskatchewan and Alberta scarcely moved at all.[59][83][176] There is little to no evidence of nomadic behavior as has been recorded in several other owls in the north.[177][178]

Dietary biology

Barred owls are opportunistic predators of the woodlands. Like the tawny owl, the barred owl usually hunts from a perch. During hunting efforts, they glide briefly from perch to perch until prey is detected.[3][11] Barred owl has incredibly large eyes that capture as much light as possible, allowing for better night vision.[179] Attacks may be carried out merely 6 to 10 m (20 to 33 ft) away from the prey due to the effectiveness of the silencing wing feathers.[180] The barred owl, especially compared to the predominantly arboreal prey of the spotted owl, usually prefers to target small animals that are terrestrial.[181] However, barred owls will also flush and capture night-roosting birds and capture bats on the wing as well.[3] Daytime hunting has been reported several times, although peak hunting time is typically shortly after sunset.[34][160][161][182] Although they usually hunt within woodlands, they not infrequently hunt in open terrain, more typical of the hunting areas of a bird like the long-eared owl.[11] Cases of snow-plunging have known been verified for barred owls, allowing them to capture prey like voles in subnivean zones that they use as hidden snow tunnels during winter, a hunting method once though particular to great grey owls.[183] While hunting squirrels in the Foothill Model Forest of Alberta, barred owls were seen to make several passes before succeeding.[184] Hunting on the ground is usually done to obtain foods such as invertebrates or amphibians.[46][185] These owls may wade into water to capture fish and may do an unusual amount of aquatic, for any Strix species or North American owl, foraging via wading into shallows.[3][11] In lab settings, a barred owl was found to be able to survive on a lower caloric value than usual by increasing the efficiency of digestion of their scanty meals through a longer digestion time, which is amongst owls probably not unique to this species.[186] Due its relatively modest foot size, it does not usually take particularly large prey.[11] However, owls in general have proportionately larger feet and more powerful grips than similarly-sized diurnal raptors, while the physiology of the daytime raptors differs. While the mechanism of the killing feet overlap, owls kill mainly with constriction and sacrifice velocity with their physiology while diurnal raptors have higher velocity and kill mainly by trauma inflicted by their enlarged talons.[187] A majority of prey of barred owls is eaten outright but, with large prey, the barred owl may eat the head first and then return to consume the remainder of the body.[185] Cases of owls of any variety scavenging on carrion are generally rare, but at least three instances of carrion-feeding by barred owls have been observed, more recently eating deer and squirrel roadkills on a remote camera in North Carolina.[188][189] The pellet of the barred owl averages about 3.5 cm (1.4 in) in diameter and 7.2 cm (2.8 in) in length.[6]

_(14750520262).jpg)

The barred owl has been known to consume a diversity of animals from different taxonomic classes. Primarily, these owls live off of small mammals.[3][12] Other vertebrates are rarely neglected though, especially birds and amphibians but also occasionally reptiles and fish. For an owl its size, the barred owl also consumes a large amount of arthropods and other invertebrates.[3][171][171][190][191] One study from a wide swath of the range found that among 2234 accrued prey items, 76% were mammals, 15.8% were invertebrates, 5.8% were birds and 2.5% were other vertebrates.[192] In four other studies from different parts of the distribution, the mean balance of mammals in diet was around 64.9%, birds at around 13.4%, invertebrates at around 11.4% and different classes of vertebrates (mostly amphibians) at around 10.3%.[6][119][185][193][194] A compilation study that included a total of 7077 prey items using all metholodigies, 71.9% were mammals, 9.5% were birds, 0.6% reptiles, 6% amphibians, 1.89% fish, 1% earthworms, 0.2% gastropods, 6.5% insects and 2.4% crayfish.[171] Barred owls tend to focus on fairly small-sized prey, although are capable of attacking larger than usual prey in infrequent cases.[181][171] The mean size of prey taken is seldom estimated in the barred owls’ eastern range, although one study estimated mean size of prey in the general east was 33.5 g (1.18 oz).[195] Many more studies have estimated mean prey masses in westerly areas of sympatry with spotted owls to understand how their diets may conflict.[181] Different studies from the west (mainly Washington and Oregon) have variously estimated the mean prey sizes for barred owls at 47.7 g (1.68 oz), 56.1 g (1.98 oz), 60.2 g (2.12 oz), 103.5 g (3.65 oz) and 123.6 g (4.36 oz).[181][195][196][197]

Mammals

The predominant small mammal available in forest and woodland edge are generally small rodents, so the barred owl like other Strix owls most often relies on rodents as the primary type of food.[171] 51.5% of 7077 prey items from throughout the range were rodents.[171] Preferred rodents to be taken are voles, mice of the genus Peromyscus and assorted rats, including non-native Rattus species as well as unrelated native types like cotton rats, rice rats and woodrats. These all share with barred owls a penchance for nocturnality and crepuscular habits (although many voles are more correctly considered cathemeral)[3][8][59][198][199] While during other seasons, the diet of barred owls can be fairly diverse, the winter diet may be almost wholly confined to rodents (i.e. mammals comprising about 98.4% of the all known winter diets).[171] This was the case in winter in Montana, where 97.6% of 1153 prey items were montane voles (Microtus montanus), meadow voles (Microtus pennsylvanicus) with a possible slight mixture of other voles.[200] The diet of barred owls in a much smaller study near Urbana, Illinois during winter was less homogenous but still led by rodents, especially the meadow vole (32.3%) and white-footed mouse (Peromyscus leucopus) (23.5%).[201] A winter food study in Essex County, New Jersey found that among 118 prey items, meadow voles comprised a great majority of the prey, at 91.5% of the balance.[202] An unusual lack of diversity in barred owl pellets was found in several years of possibly aseasonal study in Ann Arbor, Michigan where of 777 prey items, 83.3% were meadow voles.[203] At Edwin S. George Preserve near the University of Michigan, the summer diet was also heavily rodent based, as among 146 prey items 37.9% were white-footed mice, 22.6% were southern bog lemming (Synaptomys cooperi) and 6.84% were meadow voles.[204] In a somewhat larger Michigan study, the North American deermouse (Peromyscus maniculatus), lead the prey at 34.9% of 321 prey items.[205] In Minnesota, the barred owl was counted as one of the leading causes of mortality of prairie voles (Microtus ochrogaster).[206] Studies of the barred owl diet in 6 urban metropolitan areas of British Columbia found that the diet was dominated by young rats of the invasive Rattus genus, comprising 52.8% of 688 prey items, well ahead of native Townsend's voles (Microtus townsendii), which were secondary at 19.2% of the diet. The average weight rats taken by owls were clearly juveniles, estimated to average 103 g (3.6 oz), although several could be anywhere from infant rat to adult rat sizes, i.e. about 25 to 300 g (0.88 to 10.58 oz).[207] The mean size of black rats (Rattus rattus) taken in Oregon was 250 g (8.8 oz), indicating that here large adults of this species were selected.[196] Beyond the typical more meadow-dwelling voles and woodland edge-dwelling native mice, larger and more forest dwelling rodents of different varieties can be of variable import.[6][197] Numerous woodrat species may be taken and may provide a hearty meal to a barred owl, at a mean body mass when taken (in Oregon) of 285 g (10.1 oz) for unidentified species.[181][196][208][209] In different areas, barred owls may regularly hunt the diverse members of the squirrel family, despite their general penchance for diurnality. Smaller squirrel varieties are usually focused on when hunted as supplement prey, such as chipmunks, averaging about 83 g (2.9 oz) among the different species they prey upon, and pine squirrels, which average about twice as large as chipmunks.[119][181][196][210] Usually juvenile specimens are focused on when taking the larger Sciurus tree squirrels, at least in summer, but presumably a mixture of yearling and/or adult Sciurus will be taken during winter.[181][201][205] The mean weight of western gray squirrels (Sciurus griseus) taken during the breeding season in Oregon was 450 g (16 oz), against a mean adult weight of around 770 g (1.70 lb).[196][211] The issue of temporal activities is less pertinent to the predator of flying squirrels, which are nocturnal. All studies of the diet of barred owls in Pacific Northwest show the importance of the northern flying squirrel (Glaucomys sabrinus) to their diet. This flying squirrel was found to comprise from about 10.9% to 20% of the diet of barred owls (either as the most or second most important prey species) and, with a mean weight of 134 g (4.7 oz) when taken, they comprised up to 25.6% of the food biomass for this owl species.[181][196][197] In Green Ridge State Forest in Maryland, although not numerically the most important prey family compared to unidentified cricetids and shrews, the southern flying squirrel (Glaucomys volans) was the most often identified prey species for barred owls.[212] Beyond the aforementioned rodent prey, more infrequently rodent prey can including various other crecetid rodents, pocket gophers, mountain beavers (Aplodontia rufa) (average weight when taken of up to 550 g (1.21 lb)) and jumping mice.[181][165][203][196] The largest known rodent prey of barred owls are adult muskrat (Ondatra zibethicus), which were estimated to weigh 1,169 g (2.577 lb) when taken.[196]

The other primary mammalian prey types are the shrews and the moles. At least a dozen species of shrew and most North American species of mole are known as prey of the barred owl.[182][171][181][196][204][210][213] 12.8% of 7077 total prey items from across the range were shrews or moles.[171] A small sample of prey in Michigan was led by the very small masked shrew (Sorex cinereus), which weighs around 4 g (0.14 oz), at 25% of 34 prey items.[210] A much larger shrew, the northern short-tailed shrew (Blarina brevicauda), at around 21 g (0.74 oz), was the leading prey in Glenwood, Minnesota at 35.8% of 81 prey items.[165] This prey species also is taken quite regularly in several other parts of the range, as well as a closely-related species.[203][205][212][213] Assorted other shrew species and the shrew-like, tiny mole, the American shrew mole (Neurotrichus gibbsii) (the smallest of the world’s moles) are regular supplement prey elsewhere, especially in the Pacific Northwest.[181][196][197][214] The most frequently taken single prey species through the Pacific Northwest, at 11.8% of 4299 total prey items of barred owls, was the 56 g (2.0 oz) coast mole (Scapanus orarius).[181] Usually, moles are secondary if relatively hearty prey elsewhere in the range.[207][215] Secondary prey that is heartier still can include several species of cottontail rabbits.[126][196][216][207][217] 3.2% of 7077 prey items from across the range for barred owls were rabbits or hares.[171] As for the often sympatric eastern cottontail (Sylvilagus floridanus) , juveniles were exclusively taken in summer in Wisconsin but presumably fully-grown ones were taken in large numbers during winter in Illinois, where they were the third most recorded prey species at 14.4% of the balance.[201][205] Even larger prey (perhaps the largest verifiable prey of all for barred owls) is the regularly taken snowshoe hare (Lepus americanus). The mean weights of these hares taken by barred owls in the Pacific Northwest was estimated at 1,000 to 1,200 g (2.2 to 2.6 lb) but the largest hare specimens killed by the barred owls were estimated to weigh about 1,400 g (3.1 lb).[181][196][197]

Bats are infrequently reported as prey in most of the range but an unusually close association was detected in Valdosta, Georgia, where most of the prey, 65% of pellet contents and 37 total bats, were southeastern myotis (Myotis austroriparius).[126][196][213] A study of bats foraging in response to playback of barred, eastern screech- and great horned owl calls shows that they did not alter their foraging behavior, indicating that they do not view owls as a considerable threat.[218] Other mammalian prey is seldom reported. Any of the three commoner species of small weasels are certain to be occasionally vulnerable to barred owls.[196][219] Larger cousins of weasels are sometimes perhaps taken as well. American mink (Neovison vison), which are around the same adult weight as a barred owl, have been known to be taken alive, although in Wisconsin only a “small mink” was reportedly taken.[205][220] Barred owls are also known predators of both the eastern spotted (Spilogale putorius) and the western spotted skunks (Spilogale gracilis), the latter estimated to weigh 606 g (1.336 lb) when taken.[196][221] Much larger mammals are sometimes recorded in the foods of barred owls, but there are few details known about the age, condition or circumstances (i.e. they may have been consumed as carrion or, perhaps more likely, young or infirm specimens were taken).[171][220] Some such prey species recorded have included the Virginia opossum (Didelphis virginiana)[201], the North American porcupine (Erethizon dorsatum)[193], the striped skunk (Mephitis mephitis)[8] and the domestic cat (Felis catus)[126]. Adults of all these species are known to count amongst the prey of great horned owls which is better suited than barred owls to take particularly large prey given its powerful morphology.[222][223]

Birds

.jpg)

Avian prey is taken throughout the range, though is usually quite secondary in import after mammals. The maximum known representation of bird prey in a barred owl food study was 25.1% in Alberta, meaning that they augment their diet less heavily with bird prey than their near equivalent in Europe, the tawny owl.[6][224][225] No specific variety of bird is subject to the most frequent predation by barred owls and birds are the most diverse class in these owl’s prey spectrum, with more than 100 species of bird known to be hunted.[34][171][181][205] About 60% of bird species in the prey spectrum and nearly 54% of the frequency (in 7077 prey items) amongst birds known to be hunted are passerines, which are generally small, active and diurnal denizens that predominate among the species composition of the woodlands inhabited by barred owls.[103][171] Medium-sized passerines in particular may be slightly preferred, with a wide array of thrushes, jays and icterids hunted. Common birds like the northern cardinal (Cardinalis cardinalis) and the American robin (Turdus migratorius) are taken fairly regularly when opportuned upon.[119][201][205][213] Smaller passerines, often around the same size as the mice and voles popular in the diet, are also regularly reported as prey.[205] Conspicuous nesting sites of barn swallow (Hirundo rustica) and purple martin (Progne subis) on manmade structures and objects were revealed via video-monitoring to suffer heavy predated by barred owls. In the case of the barn swallows, all ages of swallow as well as possibly eggs were eaten. 65 of 95 monitoring barn swallow nests were depredated by owls over a 3 year period.[226][227] The muddy bank nests of cliff swallows (Petrochelidon pyrrhonota) are also vulnerable to barred owls, while other swallow species are known to be opportunistically taken.[205][228] In more enclosed wooded areas, radio-tagging and video-monitoring of various passerines nests as well as examinations of owl pellets has shed light on the relationship of barred owls with these potential prey resources. Not only was the barred owl found to be a surprisingly routine predator at woodland passerine nests, but that an unexpected bulk of the acts of predation in studies from Missouri and Illinois were carried out during the daytime. Many different forest bird species (most frequently in Missouri and Illinois on acadian flycatchers (Empidonax virescens) and indigo buntings (Passerina cyanea)) were thusly hunted. These studies indicated that the barred owl may snatch passerines of any age, but recent fledglings are taken preferentially due to their often more conspicuous behavior and lacking ability for flighted escape. In Minnesota, about 62% of studied hermit thrush (Catharus guttatus) and ovenbird (Seiurus aurocapilla) fledglings were taken per one study, with all thrush that nested in the 50 m (160 ft) radius of the barred owl’s nests failing to produce any young. A similarly high rate of local determent by barred owls has been found for other woodland thrushes like the veery (Catharus fuscescens), the wood thrush (Hylocichla mustelina) and the varied thrush (Ixoreus naevius), with the additional finding that pre-dawn singing by certain thrushes, when their escape abilities are dulled by the dim light, endangers them to barred owl ambushes.[119][229][230][231][232] Forest birds seem to recognize the barred owl as a threat, with mobbing behavior evoked easily by playing recordings of their calls in the daytime.[233]

.jpg)

A wide diversity of bird prey may be occasionally hunted by barred owls in different circumstances. Smaller or mid-sized bird prey species known have including different species, though usually a relatively low species diversity and in low numbers, beyond swallows and thrushes of tyrant flycatchers, vireos, chickadees, wrens, mimids, tanagers, other cardinalids and finches.[34][196][204][205][212][229] Somewhat higher diversity of species are known from the sparrow and warbler families.[119][196][202][204][205][229][234][235][236] Birds down to the size of the calliope hummingbird (Selasphorus calliope), North America’s smallest hummingbird at 2.7 g (0.095 oz), may be taken by barred owls.[181][237] At the opposite end of passerine prey for barred owls, this species will sometimes take all ages of the American crow (Corvus brachyrhynchos) from very young nestlings to adults.[6][207][238] Numerous non-passerine birds are also taken, though seldom in great numbers and of low known species diversity.[171] One exceptional family is the woodpeckers, which are probably so widely taken because of their generally overlapping habitat preferences with those of barred owls. Several species of woodpecker are preyed upon almost throughout the range, including at least a half dozen in Oregon alone, from the smallest to the largest extant woodpeckers in North America.[196][239][240] Other small-to-medium-sized bird species known as prey for barred owls are: mountain quail (Oreortyx pictus)[196], northern bobwhite (Colinus virginianus)[241], grey partridge (Perdix perdix)[193], rock dove (Columba livia) & band-tailed pigeon (Patagioenas fasciata)[242], mourning dove (Zenaida macroura)[34], purple gallinule (Porphyrio martinicus)[34], killdeer (Charadrius vociferus)[220], American woodcock (Scolopax minor)[243], least tern (Sternula antillarum)[244], snowy egret (Egretta thula)[245], cattle egret (Bubulcus ibis)[246] and belted kingfisher (Megaceryle alcyon)[205]. The largest avian prey for barred owls are common ostriches. Although they take many chicks of gamebirds, adults of these species are vulnerable as well.[34] In many areas, the ruffed grouse (Bonsana umbellus) are not infrequently taken, comprising up to nearly 6% of prey items in Alberta. In Oregon, the weights estimated for ruffed grouse taken by barred owls varied enormously, from small chicks, estimated at 25 g (0.88 oz), to adults weighing about 576 g (1.270 lb). Broader study in the Pacific Northwest indicated that adult ruffed grouse were mainly taken.[119][181][196][247] Barred owls are also known to take adult spruce grouse (Falcipennis canadensis), of about the same size as the ruffed grouse, as well as much larger species including the common pheasant (Phasianus colchicus) and the sooty grouse (Dendragapus fuliginosus), the latter estimated to average 1,050 g (2.31 lb) when taken.[193][196][248] Barred owls are also known to be predators of the young of other larger birds such as the American white ibis (Eudocimus albus) and wild turkey (Meleagris gallopavo).[249][250]

Other prey

Barred owl predation on reptiles is widely reported but they seldom take large numbers in any given area.[171] Most reported instances of such captures are of various small lizards, often of skinks in the genus Plestiodon most often from the Midwest to the western parts of the range.[34][165][251][252] Several reported instances of barred owls hunting snakes are also known, but they are perhaps even more seldomly preyed upon than lizards.[34][196] More than a half dozen snake species are known to be captured, several of which are harmless snakes.[253][254][255] The estimated body mass of black racer (Coluber constrictor) taken in Oregon was only 77 g (2.7 oz), well under their mean mature size.[196] However, consumption or predation on dangerous pit vipers, such as timber rattlesnakes (Crotalus horridus) and copperheads (Agkistrodon contortrix), by barred owls has been reported, although it is not known whether these are taken as adults.[8][34][256] Rarer still is barred owl predation on turtles.[171] Predation by this species was reported upon a very young river cooter (Pseudemys concinna), which had a carapace width of only 31.4 mm (1.24 in), as well as on juvenile gopher tortoise (Gopherus polyphemus) and apparently diamondback terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin).[34][257][258] Much more characteristic than any reptilian prey are amphibians, with both various types of frogs and their kin and salamanders and theirs reported in this owl’s foods.[34][171] Amphibians were more considerably more popular in the diet in western part of range, comprising 10.5% of known studies against 4.4% in the east.[171] In total, well over 20 amphibian species have been identified in the foods of barred owls and amphibians collectively can make up to 24.5% of the local diet (as was reported in Alberta).[6][119][171] While salamanders and newts are probably often visually discerned while scanning the forest floor, many frogs are probably hunted down auditorily during their crepuscular choruses.[59][259] Amphibians are taken almost entirely during the breeding season, as they become unavailable to barred owls during the winter months.[181][196] Most reported amphibian prey in Oregon were unidentified “medium-sized salamanders”, estimated to average 14 g (0.49 oz).[196] The smallest salamander hunted may be the red-backed salamander (Plethodon cinereus), which averages about 0.5 g (0.018 oz) (thus perhaps the smallest barred owl vertebrate prey), to the greater siren (Siren lacertina) which averages about 74.9 g (2.64 oz) but is capable of reaching weights of more than 700 g (1.5 lb)}.[194][260][261][262] A diversity of frog sizes may be taken, varying potentially in size from spring peepers (Pseudacris crucifer), which average around 4 g (0.14 oz), to American bullfrogs (Lithobates catesbeianus), which average around in mature bullfrogs 430 g (15 oz).[263][264] A notable act of successful predation was carried out by a barred owl on a rough-skinned newt (Taricha granulosa), which contains toxins that are often deadly to predators. Apparently, the owl was able to survive after consuming the newt.[265] The rarest variety of vertebrate prey to barred owls are fish.[171] However, there are several accrued accounts of fishing by these owls, including older accounts of barred owls coming to ice holes made by human fishermen and more recent accounts of possibly routine fishing by the owls on the St. Johns River in Florida, in the latter case utilizing a fishing dock as a hunting perch.[34][266] At least five species of fish have been identified in the foods of barred owls, including fairly large fish like the brown bullhead (Ameiurus nebulosus) and the largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides).[8][34][196][267] An usual amount of fish were found in studies from Missouri in some years, up to 8.4%, but in several years none were found.[220]

.jpg)

The balance of assorted invertebrates in the diet of barred owls can be quite high. Although many of those found in pellets are unidentified to species, nearly 40 species of invertebrates have been found in their foods.[34][171][196] Broad studies indicate arthropods (including millipedes and spiders but predominantly insects) in general comprise up to about 16% of the barred owl’s foods.[192][181] When hunting insects, barred owls most often prefer ground-based beetles. In Oregon, 11.7% of the diet was assorted beetles (14 species were identified), being somewhat more numerous among 3686 prey items than other non-rodent prey orders.[196] However, some insects prey such as luna moth (Actias luna), eastern tiger swallowtail (Papilio glaucus) and green darner (Anax junius) are presumably hawked on the wing around dawn and dusk.[8][34][171] It is known that barred owls will sometimes come hunt nearby manmade light sources and campfires, flying out from the perch to quickly capture flying insects that were attracted to them.[34][239] Of 123 prey items found in southern Manitoba, flighted Sphinx moths and flightless scarab beetles each comprised 7% (most of the remaining balance being unidentified mammals and birds).[215] Crayfish of at least four identified species are another widely taken type of invertebrate, often presumably snatched up by barred owls from shallow waterways.[171][196][165][268][269] Crayfish seem to be exclusively taken in the east and Midwest, areas where they comprised 3.4% of all known food studies, and none at all were recorded in the western part of the range.[171] In Missouri, annually up to 31.1% (though, in some years, 0%) of the diet was comprised by crayfish.[220] Several cases as well are known of barred owls feeding off of snails and slugs, the latter especially in the Pacific Northwest.[3][190] In cases where they take white-lipped snails (Cepaea hortensis), they appear to routinely crush the shells of this prey.[190][270] Another snail, the Pacific sideband (Monadenia fidelis), was surprisingly often present in the foods in Oregon as at least 135 taken.[196] Beyond slugs, other “soft” invertebrates are sometimes hunted, especially earthworms. Earthworms were most prominent in the foods of barred owls in Nova Scotia, where 27.6% of 186 video-monitored prey deliveries in Nova Scotia were worms, in fact the most regularly delivered of all prey types there.[185][190]

Interspecies predatory relationships

The barred owl overlaps in range with multiple other predators of similar prey species with the most overlap, going on temporal activity, likely to be with other owls. Of the owls in North America about three-quarters of the species are reliant on similar small mammal prey, usually rodents, with a mixture of other prey genera as supplements.[15] Other than its ecology where it today co-exists with spotted owls, however, there is some level of niche differentiation from a majority of sympatric owls.[8] In the eastern forest biome, the barred owl is the only large owl species to dwell mainly in continuous forest areas.[8][6][195] While many of the owls sympatric with barred owls over the lion’s share of their eastern and Midwestern range share a preference for hole-nesting, smaller hole-nesting owls usually prefer different habitats, such as the open country-dwelling barn owl (Tyto alba) and the screech-owls which usually in North America dwell at the interface of forest and open habitats.[8][59] Both North American species in the Aegolius owl genus are forest-dwelling cavity nesters but are, of course, much smaller and are at entirely different trophic levels.[8][59][129] A singular diurnal raptorial species that mirrors the barred owl at nearly all ecological levels, is the red-shouldered hawk (Buteo lineatus). Both species have similar distributions, habitat preferences and somewhat similar dietary habits and trophic level. They may considered as nearly nocturnal and diurnal ecological equivalents.[6][271] In multiple parts of the range, including southwestern Ohio, North Carolina and northern Michigan, the paralleling habitat usage and nesting behavior of the barred owl and red-shouldered hawk has been noted. One of the few respects in which their habitat usage differs is that the barred owl is more adaptive to nesting in suburban areas if they have old growth trees that provide plentiful tree hollows whereas the red-shoulders tend to avoid suburban areas whilst nesting. During the winter, on the contrary, red-shoulders may acclimate favorably to suburban areas while the barred owls seldom alter their range and remain more or less constrained to the stands they used during nesting.[114][272][273] The red-shouldered hawk averages somewhat smaller and has a more limited prey spectrum than barred owls, but probably goes after dangerous prey such as snakes quite a bit more regularly.[8][34][274] Multiple occasions are recorded where the barred owl and red-shouldered hawk have nested in the same area, often within the same grove of trees, remarkably with little to no conflicts.[6][59] At least one nest was found including eggs from both species.[34] When nesting near other hawks, like red-tailed hawks (Buteo jamaicensis) and Cooper's hawks (Accipiter cooperii), the relationship tends to be much more contentious between hawk and owl despite barreds sometimes sharing space or using the old nests of these hawks.[8] A wing-clapping display by a pair of barred owls was recorded during antagonistic encounters in Manitoba with a pair of broad-winged hawks (Buteo platypterus) (wing-claps were previously not recorded in this species and when recorded for other owl species were often for the purposes of courtship displays).[275]

.jpg)

One predator that is a major source of conflict for the barred owl is the great horned owl.[6] In every part of their range, barred owls are compelled to share space with the larger owls.[8] There is habitat partitioning between the barred owl and great horned owl that allows them to often co-exist. Great horned owls prefer various more open habitats mixed with trees, often in rather upland areas, which differs from the habitats preferred by the barred owl.[8][59] If a great horned owl moves into an area, barred owls appear to avoid said areas based on radiotelemetry.[104][276] In much of the east, habitat alteration and fragmentation tends to favor the great horned owl and conversely be at the expense of the barred owl. Where more continuous forest is available, however, the great horned and barred owl can occur surprisingly close to one another. In one case, a barred owl was observed to roost only 400 m (1,300 ft) from a great horned owl.[104][277][278][279] In general the reforestation at the northern sections of the Great Plains have, on the contrary, benefited barred owls (and may have been a part of allowing their westward expansion) and been perhaps slightly detrimental to the great horned owl.[64] However, even where the habitat becomes less ideal, the great horned owl is unlikely to vacate an area, unlike the barred owl which can be entirely displaced if woods become too small and fragmented.[6][75] There are similarities in the dietary habits of the great horned owl and barred owl, as both are wide-ranging, large and opportunistic owls.[15][59] However, the great horned owl is considered larger in bulk, sometimes averaging nearly twice as heavy, with much heavier, larger feet and talons.[8][192] The great horned owl is provably rather more powerful[187] and access a larger prey spectrum than barred owls, which additionally take considerably fewer prey species because they occur in more limited habitats and have a much smaller overall distribution.[8][34][195][280][281] A study utilizing stable isotopes in Alberta appeared to confirm that the great horned owl preys on nearly twice as many prey species as do the barred owls of the area.[282]

The great horned owl is indeed likely to be the greatest natural enemy of the barred owl.[8][34][283] There are several accounts of the horned owl species preying on nestlings, fledglings and adults of the barred.[6][34][110][284] Other than horned owls, predation of the barred owl seems to be fairly rare outside of the nestling age, both due to the owl’s relatively large size and their nesting habits, most often in secluded tree hollows.[6] One more virulent nest predator is likely to be raccoons (Procyon lotor), which can easily nearly decimate both tree hollow and stick nests locations of more or less any kind of bird especially in peri-urban areas where they can largely exist without larger controlling predators.[185][285] Both the American marten (Martes americana) and the fisher (Pekania pennanti) are known to be nest predators of barred owls, in turn appearing to cause the owls to switch nest sites.[286] Other birds of prey may be an occasional threat to barred owls. Northern goshawks (Accipiter gentilis) have reportedly killed both young and adult barred owl.[6][34] One modern accounts mentions predation by a goshawk on a nestling barred owl (i.e. weight about 392 g (13.8 oz)).[287] A well-known instance of a goshawk attack on an adult barred owl concluded with both the owl and goshawk killing one another.[8][288] There are some very rare, singular cases of predation on barred owls (age unknown) by red-tailed hawks (Buteo jamaicensis), which nonetheless generally appears to be a less menacing co-inhabitant than the goshawk.[34][289] More surprisingly, a Cooper's hawk (Accipiter cooperii), a smaller species of raptor, was observed to apparently prey upon a full-grown barred owl in British Columbia.[290] An apparent instance of predation on a barred owl was reportedly committed by an American alligator (Alligator mississipensis).[291]

On the other hand, the barred owl is a not inconsiderable predator of smaller raptorial birds as well. Most smaller owls that co-exist with barred owls are at occasional risk of predation.[8] A particular cause of concern in intraguild predations by the barred has been their encroachment into the areas inhabited by western screech-owl (Megascops kennicotti). Several instances of predation have been noted on the screech-owls and the recent, unprecedented presence of the barred owls appears to have a correlation with the decline of the western screech-owl in British Columbia and in Bainbridge Island, Washington.[196][292][293] In one instance, a biologist who called in a eastern screech-owl (Megascops asio) in Ohio observed it to be immediately captured and consumed by a barred owl. The barred owl is a serious predator of eastern screech-owls but is less deadly to them in general than the great horned owl.[294][295] Various additional owl species known to be preyed by barred owls including the flammulated owl (Psiloscops flammeolus)[296], northern pygmy owl (Glaucidium gnoma)[181], northern saw-whet owl (Aegolius acadius)[196] and long-eared owl (Asio otus)[34]. The interspecific owl trophic chain was perhaps most conspicuous in a case where a barred owl that was shot in New England was found to have a long-eared owl inside its stomach which in turn had an eastern screech-owl in its own stomach.[8][34] More unexpectedly, barred owls may even prey on other Strix species. As many as four records of circumstantial but likely predation by barred owls on spotted owls have been reported.[181][297] A likely event of predation by a barred owl on an adult great grey owl was observed. The authors hypothesized that the victim may have been a smaller male great grey owl (which can be about the same body mass as a large female barred) but this is the only known instance to date of a great gray owl being killed by another species of Strix owl.[298] Barred owls have been known to take adults (or full-grown juveniles) of diurnal raptors as well including snail kite (Rostrhamus sociabilis), Cooper's hawk, sharp-shinned hawk (Accipiter striatus) and possibly the swallow-tailed kite (Elanoides forficatus).[239][299][300][301][302]

Reproduction

Historically, the breeding ecology of barred owls, relative to the extensive research usually carried out for North American birds of prey, was fairly poorly known, mostly due to its habit of nesting in secluded, perhaps inaccessible nesting sites.[212][273] The barred owl’s usual preferred a nest site is usually the hollow trunk of a large tree or the broken-off snag from a large tree branch. Hollows or snags may be made by any variety of sources, often due to a disease or storm, with hollows and snags large enough to accommodate these birds usually only occurring in an old-growth tree.[11][34][54][212] Typically nest sites are in rather deep and dark wooded areas, often with a well-developed understory but somewhat sparse lower branches and may be fairly close to water.[3][166][303] Average nest heights are between 6.8 and 13.4 m (22 and 44 ft) above the ground.[6] In a Saskatchewan study, 15 nests were in four assorted tree species, which had a mean nest tree height of 18.8 m (62 ft), a mean nest hollow height of 13.3 m (44 ft) and averaged about 430 m (1,410 ft) from the nearest opening (usually a road).[304] In 25 studies from throughout the range, mean nest tree height was 18.2 m (60 ft) (lowest mean from Florida where it was 5.9 m (19 ft); the highest from Oregon where it was 28 m (92 ft)), mean nest tree diameter was 65.7 cm (25.9 in) (thinnest mean in Saskatchewan at 47.4 cm (18.7 in); thickest in Washington at 106 cm (42 in)), while the mean height of the tree cavity used from these studies was 9.8 m (32 ft).[171] A big beech with a rotting core, encompassing a large cavity reached through a deep crevice, is an ideal nest site.[11] The most widely reported nesting trees in breeding cards were elms (21%) and beeches (15%), followed by oaks, hickories, yellow birches (Betula alleghaniensis), sycamores, aspens, maples and poplars.[305] In Washington, the most often used nest trees were balsam poplar (Populus balsamifera), Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) and grand fir (Abies grandis).[9] Balsam poplar comprised 62% of known nest sites in Manitoba as well.[215] It was found in Maryland that snags used were significantly higher than the average height of miscellaneous snags available in environment. The mean size of tree holes the owls used in Maryland was 33 cm (13 in) in inside diameter and 54 cm (21 in) in depth.[212] These were slightly larger than the average from Michigan, which hollow used averaged 25 cm (9.8 in) in mean diameter and 35 cm (14 in) in mean depth.[273] Record depth tree cavities used by barred owls was around 2.4 m (7.9 ft) deep from the opening on the tree.[34] One study of cavity nesting birds in Ontario found that the barred owl preferred to nest in the most massive trees of any cavity-nester in the study area.[306] In continuous bottomland forest, nests are often about every 226 ha (560 acres).[307] Territory lines often remain the same even after the original owls are replaced entirely by a new pair.[99] It was thought in Nova Scotia that some pairs may prospect a potential nest site as much as year before they use it.[185] Despite usually using sickly or dying trees, some nests have found in partially hollow but still living oaks.[3]