Balalaika

The balalaika (Russian: балала́йка, pronounced [bəɫɐˈɫajkə]) is a Russian stringed musical instrument with a characteristic triangular wooden, hollow body, fretted neck and three strings. Two strings are usually tuned to the same note and the third string is a perfect fourth higher. The higher-pitched balalaikas are used to play melodies and chords.The instrument generally has a short sustain, necessitating rapid strumming or plucking when it is used to play melodies. Balalaikas are often used for Russian folk music and dancing.

Boy with Balalaika, painting by Russian artist Nikolay Petrovich Bogdanov-Belsky | |

| String instrument | |

|---|---|

| Classification | Plucked string instrument |

| Hornbostel–Sachs classification | 321.321 (Composite chordophone) |

| Developed | Late 18th to early 19th centuries late 20th century |

| Playing range | |

| |

| Related instruments | |

|

Baglama Topshur | |

| More articles or information | |

The balalaika family of instruments includes instruments of various sizes, from the highest-pitched to the lowest: the piccolo balalaika, prima balalaika, secunda balalaika, alto balalaika, bass balalaika, and contrabass balalaika. There are balalaika orchestras which consist solely of different balalaikas; these ensembles typically play Classical music that has been arranged for balalaikas. The prima balalaika is the most common; the piccolo is rare. There have also been descant and tenor balalaikas, but these are considered obsolete. All have three-sided bodies; spruce, evergreen, or fir tops; and backs made of three to nine wooden sections (usually maple).

The prima balalaika, secunda and alto are played either with the fingers or a plectrum (pick), depending on the music being played, and the bass and contrabass (equipped with extension legs that rest on the floor) are played with leather plectra. The rare piccolo instrument is usually played with a pick.[1]

Etymology

The earliest mention of the term balalaika dates back to a 1688 Russian document.[2] Another appearance of the word is registered in a document from Verkhotursky district of Russia, dated October 1700. It also mentioned in a document signed by Peter the Great dated 1714 regarding wedding celebrations of N.M. Zotov in Saint Petersburg. In Ukrainian language the word was first documented in the 18th century as "balabaika", this form is also present in South Russian dialects and Belorussian language, as well in Siberian Russia.[3][4] It made its way to literature and first appeared in "Elysei", a 1771 poem by V. Maykov. "Balalaika" also appears in Nikolai Gogol's Dead Souls, written between 1837 and 1842.

Types

The most common solo instrument is the prima, which is tuned E4–E4–A4 (thus the two lower strings are tuned to the same pitch). Sometimes the balalaika is tuned "guitar style" by folk musicians to G3–B3–D4 (mimicking the three highest strings of the Russian guitar), whereby it is easier to play for Russian guitar players, although classically trained balalaika purists avoid this tuning. It can also be tuned to E4–A4–D5, like its cousin, the domra, to make it easier for those trained on the domra to play the instrument, and still have a balalaika sound.[5] The folk (pre-Andreev) tunings D4–F♯4–A4 and C4–E4–G4 were very popular, as this makes it easier to play certain riffs.[6]

The balalaika has been made the following sizes:[7]

Name Length Common tuning descant[lower-alpha 1] c. 46 cm (18 in) E5 E5 A5 piccolo[lower-alpha 2] c. 61 cm (24 in) B4 E5 A5 prima[lower-alpha 3] 66–69 cm (26–27 in) E4 E4 A4 secunda[lower-alpha 3][lower-alpha 4] 68–74 cm (27–29 in) A3 A3 D4 alto[lower-alpha 3] 81 cm (32 in) E3 E3 A3 tenor[lower-alpha 1] 91–97 cm (36–38 in) E3 A3 E4 bass[lower-alpha 3] 104 cm (41 in) E2 A2 D3 contrabass[lower-alpha 2][lower-alpha 3] 130–165 cm (51–65 in) E1 A1 D2

- Obsolete

- Rare

- Members of the modern balalaika orchestra

- Secundas are often the same instrument as primas, just tuned to a lower pitch range

Factory-made six-string prima balalaikas with three sets of double courses are also common. These have three double courses similar to the stringing of the mandolin and often use a "guitar" tuning.[8]

Four string alto balalaikas are also encountered and are used in the orchestra of the Piatnistky Folk Choir.

The piccolo, prima, d secunda balalaikas were originally strung with gut with the thinnest melody string made of stainless steel. Today, nylon strings are commonly used in place of gut.[9]

Amateur and/or souvenir-style prima balalaikas usually have a total of 16 frets, while in professional orchestra-like ones that number raises to 24.[9]

Technique

An important part of balalaika technique is the use of the left thumb to fret notes on the lower string, particularly on the prima, where it is used to form chords. Traditionally, the side of the index finger of the right hand is used to sound notes on the prima, while a plectrum is used on the larger sizes.

Because of the large size of the contrabass's strings, it is not uncommon to see players using plectra made from a leather shoe or boot heel. The bass balalaika and contrabass balalaika rest on the ground, on a wooden or metal pin that is drilled into one of its corners.

History

It is possible that the emergence and evolutionary of balalaika was a product of interaction with Asian-Oriental cultures too. In addition to European culture, early Russian states, also called Rus' or Rusi, were also influenced by Oriental-Asian cultures.[10][11] Some theories say that the instrument descended from the domra, an instrument from the East Slavs. In the Caucasus, similar instruments such as the Mongolian topshur, used in Kalmykia, and the Panduri used in Georgia are played. It is also similar to the Kazakh dombra, which has two strings[12]

The pre-Andreyev period

Early representations of the balalaika show it with anywhere from two to six strings, which resembles certain Central Asian instruments. Similarly, frets on earlier balalaikas were made of animal gut and tied to the neck so that they could be moved around by the player at will (as is the case with the modern saz, which allows for the playing distinctive to Turkish and Central Asian music).

The first known document mentioning the instrument dates back to 1688. A guard's logbook from the Moscow Kremlin records that two commoners were stopped from playing the Balalaika whilst drunk.[13] Further documents from 1700 and 1714 also mention the instrument. In the early 18th century the term appeared in Ukrainian documents, where it sounded like "Balabaika". Balalaika appeared in "Elysei", a 1771 poem by V. Maikov.[14] In the 19th century, the balalaika evolved into a triangular instrument with a neck that was substantially shorter than that of its Asian counterparts. It was popular as a village instrument for centuries, particularly with the skomorokhs, sort of free-lance musical jesters whose tunes ridiculed the Tsar, the Russian Orthodox Church, and Russian society in general.[15]

The Andreyev period

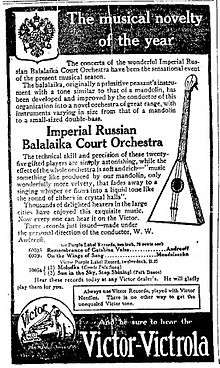

In the 1880s, Vasily Vasilievich Andreyev, who was then a professional violinist in the music salons of St Petersburg, developed what became the standardized balalaika, with the assistance of violin maker V. Ivanov. The instrument began to be used in his concert performances. A few years later, St. Petersburg craftsman Paserbsky further refined the instruments by adding a fully chromatic set of frets and also a number of balalaikas in orchestral sizes with the tunings now found in modern instruments. One of the reasons why the instruments were not standardised, was because people in the outlying areas built their own instruments, because there was so little communication for them. There were no roads and weather conditions were generally bad. Andreyev patented the design and arranged numerous traditional Russian folk melodies for the orchestra. He also composed a body of concert pieces for the instrument.[16]

Balalaika orchestra

The end result of Andreyev's labours was the establishment of an orchestral folk tradition in Tsarist Russia, which later grew into a movement within the Soviet Union.[17] The balalaika orchestra in its full form consists of balalaikas, domras, gusli, bayan, Vladimir Shepherd's Horns, garmoshkas and several types of percussion instruments.

With the establishment of the Soviet system and the entrenchment of a proletarian cultural direction, the culture of the working classes (which included that of village labourers) was actively supported by the Soviet establishment. The concept of the balalaika orchestra was adopted wholeheartedly by the Soviet government as something distinctively proletarian (that is, from the working classes) and was also deemed progressive. Significant amounts of energy and time were devoted to support and foster formal study of the balalaika, from which highly skilled ensemble groups such as the Osipov State Russian Folk Orchestra emerged. Balalaika virtuosi such as Boris Feoktistov and Pavel Necheporenko became stars both inside and outside the Soviet Union. The movement was so powerful that even the renowned Red Army Choir, which initially used a normal symphonic orchestra, changed its instrumentation, replacing violins, violas, and violoncellos with orchestral balalaikas and domras.[18]

Solo instrument

Often musicians perform solo on the balalaika. In particular, Alexey Arkhipovsky is well known for his solo performances.[19] In particular, he was invited to play at the opening ceremony of the second semi final of the Eurovision Song Contest 2009 in Moscow because the organizers wanted to give a "more Russian appearance" to the contest.[20]

In popular culture

Through the 20th century, interest in Russian folk instruments grew outside of Russia, likely as a result of western tours by Andreyev and other balalaika virtuosi early in the century. Significant balalaika associations are found in Washington, D.C.,[21] Los Angeles,[22] New York,[23] Atlanta[24] and Seattle.[25]

- Ian Anderson plays balalaika on two songs from the 1969 Jethro Tull album Stand Up: "Jeffrey Goes to Leicester Square" and "Fat Man".[26]

- Wes Anderson's 2014 film The Grand Budapest Hotel (winner of the 87th Academy Award for Best Original Score)[27] employs many balalaikas in both Alexandre Desplat's original score and several sound-track recordings by the Osipov State Russian Folk Orchestra.

- Oleg Bernov of the Russian-American rock band the Red Elvises played a red electrified contrabass balalaika during the band's North American tours. Dejah Sandoval currently tours with the Red Elvises and plays the bass balalaika.

- Kate Bush, featured the balalaika (played by her brother Paddy Bush) in two of her Top-40 singles, "Babooshka" and "Running Up That Hill".[28]

- Katzenjammer, the Norwegian all-girl pop band, uses two contrabass balalaikas, both of which have cat faces painted on the front. They are named Børge and Akerø.[29][30]

- David Lean's 1965 film Doctor Zhivago features balalaika prominently in the score and the plot.[31][32][33]

- VulgarGrad, an Australian band fronted by actor Jacek Koman, plays songs of the Russian criminal underground, and uses a contrabass balalaika.[34]

- RebbeSoul plays balalaika on numerous songs on the RebbeSoul albums Fringe Of Blue, RebbeSoul-O, Change The World With A Sound, and From Another World. He also plays balalaika on the Common Tongue album, Step Into My Word and on the Shlomit & RebbeSoul album, The Seal Of Solomon.

- The instrument is featured in the episode "The Secret war" of the 2019 Netflix series "Love, Death and Robots"

- The instrument is used alongside a piano and an accordion in the piece "A Journey" from the soundtrack of the 2013 animation "The Wind Rises"

- Selo i Ludy, a Ukrainian folk band, utilises the balalaika

References

- "The Washington Balalaika Society". www.balalaika.org. Archived from the original on 1 March 2009.

- Belinskiy, Dmitry. "Balalaika". Krymskaya Pravda. Balalaika music, video.

- Історичний словник українського язика Під ред. Є. Тимченка; укл.: Є. Тимченко, Є. Волошин, К. Лазаревська, Г. Петренко. — К.-Х., 1930–32. — Т. 1. — XXIV + 948 с. Зошит 1: А — Глу. — С. 52.

- Felinska, Ewa; Lach-Szyrma, Krystyn (1852). Revelations of Siberia. University of Michigan. London, Colburn and co.

- How to tune a Balalaika

- Micha Tcherkassky. "Balalaika.fr – Origins of balalaika".

- Ekkel, Bibs; The Complete Balalaika Book; Mel Bay Publications; Pacific, Missouri: 1997. pg. 90–92. ISBN 0-7866-2475-2

- What is a balalaika?

- Basic Information

- Kim, Hyun Jin, 1982- (19 November 2015). The Huns. Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon. p. 157. ISBN 9781317340904. OCLC 930082848.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Chamberlin, William Henry (1960). "Russia between East and West". The Russian Review. 19 (4): 309–315. doi:10.2307/126474. ISSN 0036-0341. JSTOR 126474.

- Findeizen, Nikolai. History of Music in Russia from Antiquity to 1800. Ed. Miloš Velimirović and Claudia Jensen. Vol. 1. Bloomington, IN: Indiana UP, 2008. P. 172.

- "Balalaika orchestra offers glimpse of instruments, music". The Daily Progress. 28 September 2012. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- Аверин, В. А. Балалаечное исполнительство в Сибири: Опыт монографического исследования. Енисейский летописец (2013). pp. 31-33.

- Шанский Н. М., Иванов В. В., Шанская Т. В. Скоморох // Краткий этимологический словарь русского языка. Пособие для учителя / Под ред. чл.-кор. АН СССР С. Г. Бархударова. — М.: Просвещение, 1971. p. 412

- Прохоров, А. М., ed. Большая Советская Энциклопедия. 3rd ed. Vol. 2. Москва: Советская Энциклопедия, 1970. pp. 16-17.

- Smith, Susannah L. "Folk Music." Encyclopedia of Russian History. Ed. James R. Millar. Vol. 2. New York: Macmillan Reference USA, 2004. p. 510.

- Schwarz, Boris. Music and Musical Life in Soviet Russia. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1983. p. 495.

- "Алексей Архиповский". Алексей Архиповский (in Russian). Retrieved 16 October 2018.

- Алексей Архиповский: Выступлением на "Евровидении" я недоволен! (in Russian). NEWSmusic.Ru. Archived from the original on 2 January 2011. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- "The American Balalaika Symphony: Experience It!". absorchestra.org. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- "Los Angeles Balalaika Orchestra". russianstrings.com. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- "New York Russian Balalaika Orchestra". barynya.com. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- "Atlanta Balalaika Society". atlantabalalaika.com. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- "Washington Balalaika Society – Home". balalaika.org. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- "Stand Up – Jethro Tull". jethrotull.com. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- "THE 87TH ACADEMY AWARDS 2015".

- Running Up That Hill

- "Security Check Required". facebook.com. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- Akero – Its All About the Bass – Katzenjammer. 29 September 2015. Retrieved 23 February 2016 – via YouTube.

- Russell, Mark; Young, James Edward (2000). Film Music. Focal Press. pp. 48–51. ISBN 9780240804415.

Zhivago balalaika music.

- Brassard, Jeffrey (2017). "Slavophilism, nostalgia and the curse of Western ideas: Reflections on Russia's past in Alexander Proshkin's 2006 adaptation of Doctor Zhivago" (PDF). Journal of Historical Fictions. 1: 111–129 – via Google Scholar.

- Goldman, Susan R.; Graesser, Arthur C.; Broek, Paul van den (August 1999). Narrative Comprehension, Causality, and Coherence: Essays in Honor of Tom Trabasso. Routledge. p. 89. ISBN 9781135666071.

- "Band". Vulgargrad. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- Блок В. Оркестр русских народных инструментов. Москва, 1986.

- Имханицкий М. В. В. Андреев – Материалы и документы. Москва, 1986.

- Имханицкий М. У истоков русской народной оркестровой культуры. Москва, 1987.

- Имханицкий М. История исполнительства на русских народных инструментах. Москва, 2002.

- Пересада А. Балалайка. Москва, 1990.

- Попонов В. Оркестр хора имени Пятницкого. Москва, 1979.

- Попонов В. Русская народная инструментальная музыка. Москва, 1984.

- Вертков К. Русские народные музыкальные инструменты. Музыка, Ленинград, 1975.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Balalaika. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Balalaïka. |

- (en) "Balalaika"—article by Dmitry Belinskiy from the newspaper Krymskaya Pravda. Balalaika music, video

- Russian site about balalaika. History of balalaika, by Georgy Nefyodov

- Chord reference for Prima-Balalaika

- (rus) balalaika.org.ru: music sheets, video, forum, etc.

- An example of balalaika playing on YouTube

- (de) russische-balalaika.de – informative Website

- An example of a reconstructed pre-Andreyev balalaika with two strings on YouTube

- An example of a Bessarabian tune on balalaika, Dieter and Ally Hauptmann on YouTube.