Ascoli Satriano

Ascoli Satriano (Italian: [ˈaskoli satriˈaːno]; Foggiano: Àsculë) is a town and comune in the province of Foggia in the Apulia region of southeast Italy. It is located on the edge of a large plain in Northern Apulia known as the Tavoliere delle Puglie.[3]

Ascoli Satriano | |

|---|---|

| Comune di Ascoli Satriano | |

| |

Coat of arms | |

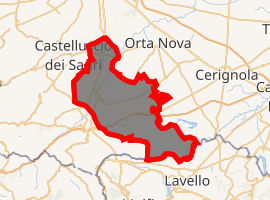

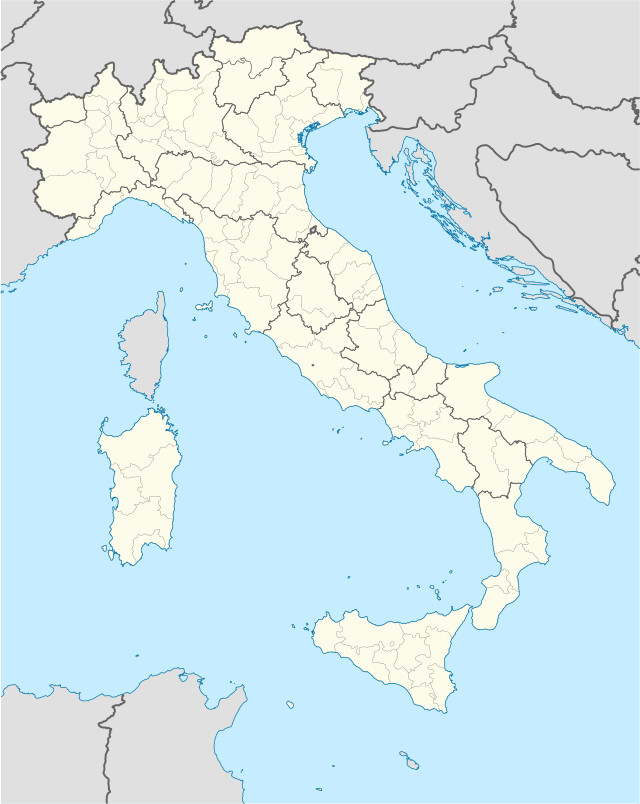

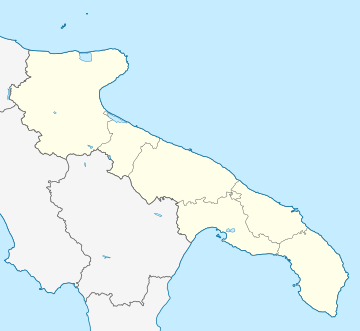

Location of Ascoli Satriano

| |

Ascoli Satriano Location of Ascoli Satriano in Italy  Ascoli Satriano Ascoli Satriano (Apulia) | |

| Coordinates: 41°12′56″N 15°33′28″E | |

| Country | Italy |

| Region | Apulia |

| Province | Foggia (FG) |

| Frazioni | San Carlo |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Vincenzo Sarcone |

| Area | |

| • Total | 333.68 km2 (128.83 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 376 m (1,234 ft) |

| Population (30 April 2017)[2] | |

| • Total | 6,188 |

| • Density | 19/km2 (48/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Ascolani |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 71022 |

| Dialing code | 0885 |

| Patron saint | San Potito |

| Saint day | January 14 |

| Website | Official website |

History

The earliest human presence in the area of Ascoli dates from around the 9th century BC, according to archaeological evidence, and similar dated earthworks are common in the area.[3]

Ascoli (known as Asculum) was a city of the Dauni.[4] It was then a small cluster of habitations in a wider network of scattered villas. The economy was operated by slave labour and focused on grain cultivation.[3] Ascoli was the site of two early Roman battles (see Battle of Asculum).[5] Later Sulla established a military colony there.

As the Western Roman Empire began to collapse in the fourth and fifth centuries, many of the surrounding farms were abandoned with a retraction of cultivation and a re-growth of woodlands.[3] In the mid-9th century the Saracens razed the city. In 1040 it rebelled against the Byzantines and, the following year, a decisive battle was fought nearby which granted the Normans control over southern Italy. An earthquake in 1456 totally destroyed Ascoli, and forced relocation of the surviving inhabitants to the site of the current town. Re-growth of the town however was interrupted by periodic outbreaks of plague and typhus into the early 19th Century.[3]

From the end of the nineteenth century the Ascoli was affected by increasing emigration to the Americas, reaching a peak between 1903 and 1914, stopping during the periods of the First World War and Italian fascism. After the bombing of Foggia in 1943, Ascoli Satriano was freed by British and American forces.

Ascoli Satriano was mentioned by the Irish writer James Joyce in his novel Ulysses.

After the Second World War, Ascoli, close to Cerignola, was the center of significant labor struggles against landlordism, sharecropping and low wages, and strikes, demonstrations and land occupations became frequent. Trade unionists and politicians made passionate speeches to organize to support the demands of the working classes in Piazza Cecco d'Ascoli (today Piazza Giovanni Paolo II).

Main sights

- The Romanesque-Gothic Cathedral (12th century)

- Church of St. John the Baptist (12th century)

- Church of the Incoronata (15th century)

- The Museum Center of Ascoli Satriano houses the Marbles of Ascoli Satriano, a set of marble artifacts from the 4th century BCE believed to been taken from a tomb of an elite prince of the region.

People

- Biagio Ciotto, American politician.

- Michele Placido, actor and film director

References

- "Superficie di Comuni Province e Regioni italiane al 9 ottobre 2011". Istat. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- All demographics and other statistics from the Italian statistical institute (Istat)

- Curtis, Daniel. Is there an ‘agro-town’ model for Southern Italy? Exploring the diverse roots and development of the agro-town structure through a comparative case study in Apulia. Continuity and Change Vol. 28 (03) December 2013, pp 377 - 419 DOI: 10.1017/S0268416013000362, Published online: 27 November 2013.

- Edlund Berry, I.; A. Small; DARMC; R. Talbert; S. Gillies; T. Elliott; J. Becker. "Places: 442487 (Ausculum)". Pleiades. Retrieved December 28, 2013.

- Information about this war can be found in Plutarch's Lives (Pyrrus 2 1), Polybius, Dionysius of Halicarnassus (XX 1—3), and Livy.

External links

- The Museum Center of Ascoli Satriano (in Italian)

- A late Roman villa at Faragola (Ascoli Satriano), ITALY Dipartimento di Scienze Umane, Area di archeologia - Università degli Studi di Foggia.