Anti-Chinese sentiment in the United States

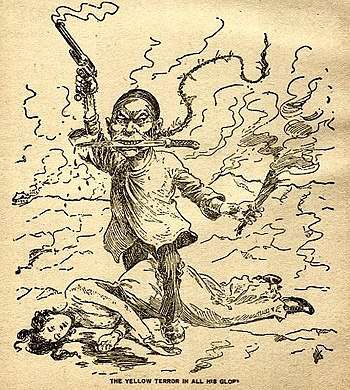

Anti-Chinese sentiment has existed in the United States since the mid-19th century, shortly after Chinese immigrants first arrived in the United States.[1] It was manifested in the 1860s, when the Chinese were employed in the building of the First Transcontinental Railroad, culminating in the federal Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which banned further Chinese immigration as well as naturalization. Its origins can be traced to the American merchants, missionaries, and diplomats who sent home from China "relentlessly negative" reports of the people they encountered there.[2] These attitudes were transmitted to Americans who never left North America, triggering talk of the Yellow Peril, and continued through the Cold War during McCarthyism. Some modern anti-Chinese sentiment may be the result of China's rise as a major world power seen to be at the expense of other countries.

%2C_by_Thomas_Nast.png)

Early Chinese immigration to the United States

Starting with the California Gold Rush in the middle 19th century, the United States—particularly the West Coast states—enlisted large numbers of Chinese migrant laborers. Early Chinese immigrant worked as gold miners, and later on subsequent large labor projects, such as the building of the First Transcontinental Railroad. The decline of the Qing Dynasty in China, instability and poverty caused many Chinese, especially from the province of Guangdong, to emigrate overseas in search of a more stable life, and this coincided with the rapid growth of American industry. The Chinese were considered by employers as "reliable" workers who would continue working, without complaint, even under destitute conditions.[3]

Chinese migrant workers encountered considerable prejudice in the United States, especially by the people who occupied the lower layers in white society, and Chinese "coolies" were used as a scapegoat for depressed wage levels by politicians and labor leaders.[4] Cases of physical assaults on Chinese include the Chinese massacre of 1871 in Los Angeles and more recently the 1982 murder of Vincent Chin in Detroit. The 1909 murder of Elsie Sigel in New York, of which a Chinese person was suspected, was blamed on the Chinese in general and led to physical violence. "The murder of Elsie Sigel immediately grabbed the front pages of newspapers, which portrayed Chinese men as dangerous to "innocent" and "virtuous" young white women. This murder led to a surge in the harassment of Chinese in communities across the United States."[5]

The emerging American trade unions, under such leaders as Samuel Gompers, also took an outspoken anti-Chinese position,[6] regarding Chinese laborers as competitors to white laborers. Only with the emergence of the international trade union Industrial Workers of the World did trade unionists start to accept Chinese workers as part of the American working-class.[7]

During this period, the phrase "yellow peril" was popularized in the U.S. by newspapers owned by William Randolph Hearst.[8] It was also the title of a popular book by an influential U.S. religious figure, G. G. Rupert, who published The Yellow Peril; or, Orient vs. Occident in 1911. Based on the phrase "the kings from the East" in the Christian scriptural verse Revelation 16:12,[9] Rupert made the claim that China, India, Japan and Korea were attacking the West, but that Jesus Christ would stop them.[10] In his 1982 book The Yellow Peril: Chinese Americans in American fiction, 1850-1940, William F. Wu states that "Pulp magazines in the 30s had a lot of yellow peril characters loosely based on Fu Manchu... Most were of Chinese descent, but because of the geopolitics at the time, a growing number of people were seeing Japan as a threat, too."[11]

Chinese Exclusion Act and legal discrimination

In the 1870s and 1880s various legal discriminatory measures were taken against the Chinese. A notable example is that after San Francisco segregated its Chinese school children from 1859 until 1870, the law was amended in 1870 to drop the requirement to educate Chinese children entirely. This led to Tape v. Hurley, 66 Cal. 473 (1885), a landmark court case in the California Supreme Court in which the Court found the exclusion of a Chinese American student, Mamie Tape, from public school based on her ancestry unlawful. However, state legislation passed at the urging of San Francisco Superintendent of Schools Andrew J. Moulder after the school board lost its case enabled the establishment of a segregated school.

The 1879 Constitution of the State of California prohibited employment of Chinese people by state and local governments, and by businesses incorporated in California. Also, it delegated power to local governments of California to remove Chinese people from within their borders.[13][14]

In 1880, the elected officials of the city of San Francisco passed an ordinance making it illegal to operate a laundry in a wooden building without a permit from the Board of Supervisors. The ordinance conferred upon the Board of Supervisors the discretion to grant or withhold the permits. At the time, about 95% of the city's 320 laundries were operated in wooden buildings. Approximately two-thirds of those laundries were owned by Chinese people. Although most of the city's wooden building laundry owners applied for a permit, only one permit was granted of the two hundred applications from any Chinese owner, while virtually all non-Chinese applicants were granted a permit.[15][16] However, this led to the 1886 Supreme Court case Yick Wo v. Hopkins, that was the first case where the Supreme Court ruled that a law that is race-neutral on its face, but is administered in a prejudicial manner, is an infringement of the Equal Protection Clause in the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.[17]

Discriminatory laws, in particular the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, were aimed at restricting further immigration from China.[18] The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 was repealed by the Chinese Exclusion Repeal Act of 1943.

Another key piece of legislation was the Naturalization Act of 1870, which extended citizenship rights to African Americans but barred Chinese from naturalization on the grounds that they and other Asians could not be assimilated into American society. Unable to become citizens, Chinese immigrants were prohibited from voting and serving on juries, and dozens of states passed alien land laws that prohibited non-citizens from purchasing real estate, thus preventing them from establishing permanent homes and businesses. The idea of an "unassimilable" race became a common argument in the exclusionary movement against Chinese Americans. In particular, even in his lone dissent against Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), then-Supreme Court Justice John Marshall Harlan wrote of the Chinese as: "a race so different from our own that we do not permit those belonging to it to become citizens of the United States. Persons belonging to it are, with few exceptions, absolutely excluded from our country. I allude to the Chinese race."[19]

In the USA xenophobic fears against the alleged "Yellow Peril" led to the implementation of the Page Act of 1875, the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, expanded ten years later by the Geary Act. The Immigration Act of 1917 then created an "Asian Barred Zone" under nativist influence.

The Chinese Exclusion Act was one of the most significant restrictions on free immigration in U.S. history. The Act excluded Chinese "skilled and unskilled laborers and Chinese employed in mining" from entering the country for ten years under penalty of imprisonment and deportation. Many Chinese were relentlessly beaten just because of their race.[20][21] The few Chinese non-laborers who wished to immigrate had to obtain certification from the Chinese government that they were qualified to immigrate, which tended to be difficult to prove.[21]

The 1921 Emergency Quota Act, and then the Immigration Act of 1924, restricted immigration according to national origins. While the Emergency Quota Act used the census of 1910, xenophobic fears in the WASP community lead to the adoption of the 1890 census, more favorable to White Anglo-Saxon Protestant (WASP) population, for the uses of the Immigration Act of 1924, which responded to rising immigration from Southern and Eastern Europe, as well as Asia.

One of the goal of this National Origins Formula, established in 1929, was explicitly to keep the status quo distribution of ethnicity, by allocating quotas in proportion to the actual population. The idea was that immigration would not be allowed to change the "national character". Total annual immigration was capped at 150,000. Asians were excluded but residents of nations in the Americas were not restricted, thus making official the racial discrimination in immigration laws. This system was repealed with the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965.

Chinese labor and the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882

According to statistics, between 1820 and 1840, only 11 Chinese people emigrated to the United States. However, many Chinese were living in distress due to the end of the Qing Dynasty. The United States offered a more stable life, thanks to the gold rush in California, the construction of railways, and the resulting large demand for labor. Beginning in 1848, many Chinese chose to immigrate to the US. California Governor John McDougal in 1851 praised the Chinese as "the most valuable immigrants" to California.[22]

In order to recruit more laborers, the United States and China signed the Burlingame Treaty in 1868.[23] The Burlingame Treaty provided several rights, including that Chinese people can freely enter and leave the United States; the right of abode in the United States; and the United States most-favored treatment of Chinese nationals in the United States. The Treaty stimulated immigration for the 20 years between 1853 and 1873, and resulted in the immigration of nearly 105,000 Chinese to the United States by 1880.[24]

1882 was an election year in California. In order to secure more votes, California politicians adopted a staunch anti-China stance. In Congress, California Republican Senator John Miller spoke at length in support of a bill to prohibit further Chinese immigrants, substantially the same as one from the prior session of Congress that had been vetoed by President Rutherford B. Hayes. Senator Miller submitted a motion to ban the immigration Chinese laborers for 20 years, citing the passage of the 1879 anti-Chinese referendums in California and Nevada by huge margins as proof of popular support.[25] The motion was discussed in the Senate over the next eight days. All the Senators from western states and most of the southern Democratic Party supported Miller's proposal, strenuously objected to the eastern states senator. After intense debate, the motion eventually passed the Senate by a vote of 29 of 15; it would go on to pass in the House of Representatives on March 23, by 167 votes to 66 votes (55 abstentions).[24]

President Chester A. Arthur vetoed the bill on April 4, 1882, as it violated the provisions of the Angell Treaty, which restricted but did not ban immigration from China. Congress was unable to overturn the veto, and passed a version of the bill that banned immigration for ten years in lieu of the original twenty-year ban. On May 6, 1882, Miller's proposal was signed by President Arthur, and became the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882.[24]

Amendments introduced during the debate over the bill prohibited the naturalization of Chinese immigrants.[24][26] After the initial ten-year ban in the Chinese Exclusion Act ended, Chinese exclusion was extended in 1892 by the Geary Act and then made permanent in 1902.[26]

The Russo-Japanese War of 1904–05 shifted Americans' fears of the Yellow Peril from China to Japan.[27]

Cold War

Anti-Chinese sentiment during the Cold War was largely the result of the Red Scare and McCarthyism, which coincided with increased popular fear of communist espionage because of the Chinese Civil War and China's involvement in the Korean War.[28] During the era, suspected Communists were imprisoned by the hundreds, and some ten or twelve thousand of them lost their jobs.[28] Many of those who were imprisoned, lost their jobs or were questioned by committees, had a real past or present connection of some kind with the Communist Party. However, for the vast majority, their potential to do harm to the nation and the nature of their communist affiliations were both tenuous.[29] Among these victims were Chinese Americans, who were suspected of being affiliated with the Communist Party of China.

Deportation of Qian Xuesen

The most notable example is that of the top Chinese scientist Qian Xuesen. Allegations were made that he was a communist, and his security clearance was revoked in June 1950.[30] The Federal Bureau of Investigation located an American Communist Party document from 1938 with his name on it, and used it as justification for the revocation. Without his clearance, Qian found himself unable to pursue his career, and within two weeks, he announced plans to return to mainland China, which had come under the government of Communist leader Mao Zedong. The Undersecretary of the Navy at the time, Dan A. Kimball, tried to keep Qian in the US:

It was the stupidest thing this country ever did. He was no more a Communist than I was, and we forced him to go.[31]

Qian would spend the next five years under house arrest, which included constant surveillance with the permission to teach without any research (classified) duties.[30] Caltech appointed attorney Grant Cooper to defend Qian. In 1955, the United States deported him to China in exchange for five American pilots captured during the Korean War. Later, he became the father of the modern Chinese space program.[32][33][34]

21st century

Modern anti-Chinese sentiment in the United States may originate from American fears of China's role as a rising power. Perceptions of China's rise have been so widespread that 'rise of China' has been named the top news story of the 21st century by the Global Language Monitor, as measured by number of appearances in the global print and electronic media, on the Internet and blogosphere, and in Social Media.[35]

In the United States 2010 elections, a significant number[36] of negative advertisements from both major political parties focused on a candidates' alleged support for free trade with China. Some of the stock images that accompanied ominous voiceovers about China were actually of Chinatown, San Francisco.[37] In particular, an advertisement called "Chinese Professor", which portrays a 2030 conquest of the West by China, used local Asian American extras to play Chinese, but the actors were not informed of the nature of the shoot.[38] Columnist Jeff Yang said that in the campaign there was a "blurry line between Chinese and Chinese-Americans."[37] Larry McCarthy, the producer of "Chinese Professor," defended his work by saying that "this ad is about America, it's not about China."[39] Other editorials commenting on the video have called the video not anti-Chinese.[36][39][40]

Chinese exclusion policy of NASA

Due to security concerns, as part of the Chinese exclusion policy of NASA, many American space researchers were prohibited from working with Chinese citizens affiliated with a Chinese state enterprise or entity.[41] In April 2011, the 112th United States Congress banned NASA from using its funds to host Chinese visitors at NASA facilities because of espionage concerns.[42] Earlier in 2010, US Representative John Culberson, had urged President Barack Obama not to allow further contact between NASA and the China National Space Administration (CNSA).[43][44]

Donald Trump 2016 campaign

In November 2015, Donald Trump promised to designate China as a currency manipulator on his first day in office.[45] He pledged "swift, robust and unequivocal" action against Chinese piracy, counterfeit American goods, and the theft of American trade secrets and intellectual property. He also condemned China's "illegal export subsidies and lax labor and environmental standards."[45]

In January 2016, Trump proposed a 45% tariff on Chinese exports to the United States to give "American workers a level playing field."[46][47] When asked about potential Chinese retaliation to the implementation of tariffs, such as sales of US bonds, Trump judged such a scenario to be unlikely: "They won't crash our currency. They will crash their economy. That's what they are going to do if they start playing that."[48] In a May 2016 speech, Trump responded to concerns regarding a potential trade war with China: "We're losing $500 billion in trade with China. Who the hell cares if there's a trade war?"[49] Trump also said in May 2016 that China is "raping" the U.S. with free trade.[50]

Donald Trump presidency

Since 2018, Trump began to increase visa restrictions on Chinese nationality students and scholars,[51][52] while many Chinese students and scholars said that they experienced delays in renewing their visas or even outright cancellations of their visas.[53][54][51] In 2018, Presidential Advisor Stephen Miller proposed banning all Chinese nationality students.[55][56][57]

According to a Gallup poll released in February 2019, China was named as the America's greatest enemy by 21% percent of respondents in US, second only Russia.[58]

In April 2019, FBI Director Christopher Wray said that China posed a "whole of a society threat".[51][59] In May 2019, Director of Policy Planning Kiron Skinner said that China "is the first great power competitor of the US that is not caucasian."[60][61][62]

The current deterioration of relations has led to a spike in anti-Chinese sentiment in the US.[63][64] According to a Pew Research Center poll released in August 2019, 60 percent of Americans have negative opinions about China, with only 26 percent holding positive views. The same poll found that China was named as America's greatest enemy by 24 percent of respondents in US, tied along with Russia.[65]

In March 2020, Trump referred to the coronavirus outbreak in the United States as the "Chinese Virus". In February 2020, the World Health Organization advised the public to not refer to Coronavirus as the "Chinese virus" or "Wuhan virus".[66][67][68][69] Additionally, the terms Wuflu and Kung Flu emerged in the United States during this period as alternative ways of referring to COVID-19. These terms are linked to Wuhan, where the virus was first detected, or China in general, via portmanteau with terms from traditional Chinese Martial Arts, Wushu and Kung Fu. Despite their playfulness, use of such terms mockingly implies the virus (which is not a flu) is China's aggressive gift to the world, and distracts from the fact that thousands of Chinese have suffered and died from the virus, particularly in Wuhan, thereby belittling the widespread suffering of Chinese under pandemic conditions.[70][71]

In May 2020, a West Virginia born Chinese-American CBS reporter questioned Trump at a White House Coronavirus briefing about his stance on testing and he told her to question China. The reporter responded to Trump asking why he singled her out to question China which led to an abrupt ending of the briefing.[72][73]

See also

- Anti-American sentiment in China

- China–United States trade war

- Red Chinese Battle Plan

- List of incidents of xenophobia and racism related to the 2019–20 coronavirus pandemic

References

- McClain, Charles J. (1994). In search of equality: the Chinese struggle against discrimination in 19th-century America. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-08337-7.

- Gyory, Andrew (1998). Closing the Gate: Race, Politics, and the Chinese Exclusion Act. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. p. 10. ISBN 9780807847398. Archived from the original on April 27, 2016. Retrieved July 27, 2019.

- Norton, Henry K. (1924). The Story of California From the Earliest Days to the Present. Chicago: A.C. McClurg & Co. pp. 283–296. Archived from the original on May 9, 2008. Retrieved October 2, 2011.

- See, e.g., http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/5046/%7C Archived July 19, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- Ling, Huping (2004). Chinese St. Louis: From Enclave to Cultural Community. Temple University Press. p. 68.

The murder of Elsie Sigel immediately grabbed the front pages of newspapers, which portrayed Chinese men as dangerous to "innocent" and "virtuous" young white women. This murder led to a surge in the harassment of Chinese in communities across the United States.

- Gompers, Samuel; Gustadt, Herman (1902). Meat vs. Rice: American Manhood against Asiatic Coolieism: Which Shall Survive?. American Federation of Labor.

- Lai, Him Mark; Hsu, Madeline Y. (2010). Chinese American Transnational Politics. University of Illinois Press. pp. 53–54.

- "Foreign News: Again, Yellow Peril". Time. September 11, 1933. Archived from the original on July 21, 2013. Retrieved October 2, 2011.

- "Revelation 16:12 (New King James Version)". BibleGateway.com. Archived from the original on November 18, 2007. Retrieved November 5, 2007.

- "NYU's "Archivist of the Yellow Peril" Exhibit". Boas Blog. August 19, 2006. Archived from the original on October 13, 2007. Retrieved November 5, 2007.

- LISA KATAYAMA. "The Yellow Peril, Fu Manchu, and the Ethnic Future". io9. Archived from the original on April 7, 2012. Retrieved October 2, 2011.

- Farwell, Willard B. (1885). The Chinese at home and abroad: together with the Report of the Special Committee of the Board of Supervisors of San Francisco on the Condition of the Chinese quarter of that city. San Francisco: A.L. Bancroft & Co. Archived from the original on June 16, 2018. Retrieved June 16, 2018.

- Article XIX of the Constitution of the State of California of 1879 Archived April 26, 2020, at the Wayback Machine

- James Whitman, "Hitler's American Model: The United States and the Making of Nazi Race Law" (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2017), p. 35

- only one out of approximately eighty non-Chinese applicants was denied a permit

- "Yick Wo v. Hopkins – Case Brief Summary". www.lawnix.com. Archived from the original on September 19, 2018. Retrieved May 3, 2016.

- Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356 (1886).

- "An Evidentiary Timeline on the History of Sacramento's Chinatown: 1882 - American Sinophobia, The Chinese Exclusion Act and "The Driving Out"". Friends of the Yee Fow Museum, Sacramento, California. Archived from the original on October 3, 2011. Retrieved March 24, 2008.

- Chin, Gabriel J. "Harlan, Chinese and Chinese Americans". University of Dayton Law School. Archived from the original on May 14, 2011. Retrieved October 2, 2011.

- "Exclusion". Library of Congress. September 1, 2003. Archived from the original on August 10, 2009. Retrieved January 25, 2010.

- "usnews.com: The People's Vote: Chinese Exclusion Act (1882)". Archived from the original on March 28, 2007.

- Chen, An (2012). "On the Source, Essence of "Yellow Peril" Doctrine and Its Latest Hegemony "Variant" – the "China Threat" Doctrine: From the Perspective of Historical Mainstream of Sino-Foreign Economic Interactions and Their Inherent Jurisprudential Principles" (PDF). The Journal of World Investment & Trade. 13: 1–58. doi:10.1163/221190012X621526. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 19, 2018. Retrieved June 19, 2018.

- Schrecker, John (March 2010). ""For the Equality of Men - For the Equality of Nations": Anson Burlingame and China's First Embassy to the United States, 1868". Journal of American-East Asian Relations. 17 (1): 9–34. doi:10.1163/187656110X523717. ISSN 1058-3947. Alternate URL Archived June 19, 2018, at the Wayback Machine

- Chin, Philip (January 2013). "The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882". Chinese American Forum. 28 (3): 8–13. Archived from the original on June 19, 2018. Retrieved June 19, 2018. Direct URLs: Part 1 Archived September 12, 2015, at the Wayback Machine Part 2 Archived September 12, 2015, at the Wayback Machine Part 3 Archived September 12, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- "Senator Miller's Great Anti-Chinese Speech". Daily Alta California. March 1, 1882. Archived from the original on June 19, 2018. Retrieved June 19, 2018.

- "Primary Documents in American History: Chinese Exclusion Act". The Library of Congress. Archived from the original on June 19, 2018. Retrieved June 19, 2018.

- Lyman, Stanford M. (Summer 2000). "The "Yellow Peril" Mystique: Origins and Vicissitudes of a Racist Discourse". International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society. Springer. 13 (4): 699. doi:10.1023/A:1022931309651. ISSN 1573-3416. JSTOR 20020056.

- Schrecker, Ellen (1998). Many Are the Crimes: McCarthyism in America. Little, Brown. p. xiii. ISBN 0-316-77470-7.

- Schrecker, Ellen (1998). Many Are the Crimes: McCarthyism in America. Little, Brown. p. 4. ISBN 0-316-77470-7.

- "Tsien Hsue-Shen Dies". November 2, 2009. Archived from the original on September 28, 2011. Retrieved October 2, 2011.

- Perrett, B. (January 7, 2008), Sea Change, Aviation Week and Space Technology, Vol. 168, No. 1, p.57-61.

- "Meet the US-trained scientist who was deported to China, and became a national hero". Pri.org. February 6, 2017. Archived from the original on October 13, 2017. Retrieved October 13, 2017.

- "Qian Xuesen, Father of China's Space Program, Dies at 98". The New York Times. November 3, 2009. Archived from the original on October 28, 2017. Retrieved December 20, 2017.

- "Qian Xuesen dies at 98; rocket scientist helped establish Jet Propulsion Laboratory". September 17, 2014. Archived from the original on January 15, 2020. Retrieved April 17, 2020.

- "21世纪新闻排行中国崛起居首位" (in Chinese). Archived from the original on September 27, 2011. Retrieved October 2, 2011.

- Chi, Frank (November 8, 2010). "In campaign ads, China is fair game; Chinese-Americans are not". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved April 17, 2020.

- Lyden, Jacki (October 27, 2010). "Critics Say Political Ads Hint Of Xenophobia". NPR. Archived from the original on November 26, 2010. Retrieved December 5, 2010.

- Yang, Jeff (October 27, 2010). "Politicians Play The China Card". Tell Me More. NPR. Archived from the original on November 25, 2010. Retrieved December 5, 2010.

- Smith, Ben (October 22, 2010). "Behind The Chinese Professor". Archived from the original on January 11, 2012. Retrieved October 2, 2011.

- Fallows, James (October 21, 2010). "The Phenomenal Chinese Professor Ad". Archived from the original on January 12, 2017. Retrieved March 5, 2017.

- Ian Sample. "US scientists boycott Nasa conference over China ban". The Guardian. Archived from the original on October 5, 2013. Retrieved October 5, 2013.

- Seitz, Virginia (September 11, 2011), "Memorandum Opinion for the General Counsel, Office of Science and Technology Policy" (PDF), Office of Legal Counsel, 35, archived (PDF) from the original on July 13, 2012, retrieved May 23, 2012

- John Culberson. "Bolden to Beijing?". United States House of Representatives. Archived from the original on September 15, 2013. Retrieved October 5, 2013.

- "NASA chief to visit China". AFP. Archived from the original on January 31, 2014. Retrieved October 5, 2013.

- Doug Palmer & Ben Schreckinger, Trump's trade views vows to declare China a currency manipulator on Day One Archived March 7, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, Politico (November 10, 2015).

- Maggie Haberman, Donald Trump Says He Favors Big Tariffs on Chinese Exports Archived July 21, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times (January 7, 2016).

- Binyamin Appelaum, On Trade, Donald Trump Breaks With 200 Years of Economic Orthodoxy Archived September 25, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times (March 10, 2016).

- "Donald Trump on the trade deficit with China". Fox News. February 11, 2016. Archived from the original on May 30, 2016. Retrieved May 24, 2016.

- "Trump: 'Who the hell cares if there's a trade war?'". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on May 21, 2016. Retrieved May 21, 2016.

- "China accused of trade 'rape' by Donald Trump". BBC News. May 2, 2016. Archived from the original on June 23, 2019. Retrieved June 23, 2019.

- Perlez, Jane (April 14, 2019). "F.B.I. Bars Some China Scholars From Visiting U.S. Over Spying Fears". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on July 14, 2019. Retrieved July 14, 2019.

- Yoon-Hendricks, Alexandra (July 25, 2018). "Visa Restrictions for Chinese Students Alarm Academia". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on July 14, 2019. Retrieved July 14, 2019.

- hermesauto (April 2, 2019). "Chinese students in limbo as wait for US visas stretches for months". The Straits Times. Archived from the original on July 14, 2019. Retrieved July 14, 2019.

- "Visas Are The Newest Weapon In U.S.-China Rivalry". NPR.org. Archived from the original on July 14, 2019. Retrieved July 14, 2019.

- "Subscribe to read". Financial Times. Archived from the original on July 14, 2019. Retrieved July 14, 2019.

- Adams, Susan. "Stephen Miller Tried To End Visas For Chinese Students". Forbes. Archived from the original on July 14, 2019. Retrieved July 14, 2019.

- Fang, Tianyu. "The Man Who Took China to Space". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on April 15, 2019. Retrieved July 14, 2019.

- Inc, Gallup (February 27, 2019). "Majority of Americans Now Consider Russia a Critical Threat". Gallup.com. Archived from the original on August 4, 2019. Retrieved July 23, 2019.

- "China 'determined to steal up economic ladder at US' expense': FBI chief". South China Morning Post. April 27, 2019. Archived from the original on July 14, 2019. Retrieved July 14, 2019.

- Diplomat, Ankit Panda, The. "A Civilizational Clash Isn't the Way to Frame US Competition With China". The Diplomat. Archived from the original on June 4, 2019. Retrieved July 14, 2019.

- "Were US official's 'clash of civilisations' remarks a slip or something else?". South China Morning Post. May 25, 2019. Archived from the original on July 14, 2019. Retrieved July 14, 2019.

- Musgrave, Paul. "The Slip That Revealed the Real Trump Doctrine". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on August 7, 2019. Retrieved July 14, 2019.

- Swanson, Ana (July 20, 2019). "A New Red Scare Is Reshaping Washington". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on July 20, 2019. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- "Caught in the middle: Chinese-Americans feel heat as tensions flare". South China Morning Post. September 25, 2018. Archived from the original on August 3, 2019. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- "U.S. Views of China Amid Trade War Turn Sharply Negative". Pew Research Center's Global Attitudes Project. August 13, 2019. Archived from the original on August 14, 2019. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- Wu, Nicholas. "GOP senator says China 'to blame' for coronavirus spread because of 'culture where people eat bats and snakes and dogs'". USA TODAY. Archived from the original on March 29, 2020. Retrieved March 19, 2020.

- Forgey, Quint. "Trump on 'Chinese virus' label: 'It's not racist at all'". POLITICO. Archived from the original on March 18, 2020. Retrieved March 18, 2020.

- Fischer, Sara. "The WHO said to stop calling it "Chinese" coronavirus, but Republicans didn't listen". Axios. Archived from the original on March 29, 2020. Retrieved March 19, 2020.

- Filipovic, Jill. "Trump's malicious use of 'Chinese virus'". CNN. Archived from the original on March 29, 2020. Retrieved June 6, 2020.

- "Trump doubles down on 'China virus,' demands to know who in White House used phrase 'Kung Flu'". Fox News. March 18, 2020. Retrieved March 18, 2020.

- "A last, desperate pivot: Trump and his allies go full racist on coronavirus". Salon. March 19, 2020. Archived from the original on March 29, 2020. Retrieved March 19, 2020.

- Choi, David. "'Why are you saying that to me': Chinese American reporter calls Trump out on his anti-China remarks and suggests he's singling her out". Business Insider. Archived from the original on May 14, 2020. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- Ellison, Sarah; media, closeSarah EllisonReporter covering; Politics, Its Intersection with; writerEmailEmailBioBioFollowFollow, technologyEmailEmailBioBioFollowFollowElahe Izadi closeElahe IzadiPop culture. "Trump's 'ask China' response to CBS's Weijia Jiang shocked the room — and was part of a pattern". Washington Post. Archived from the original on May 15, 2020. Retrieved May 14, 2020.