Ornithocheiromorpha

Ornithocheiromorpha (from Ancient Greek, meaning "bird hand form") is a group of pterosaurs within the suborder Pterodactyloidea. Fossil remains of this group date back from the Early to Late Cretaceous periods (Valanginian to Turonian stages), around 140 to 94 million years ago. Ornithocheiromorphs were discovered worldwide, except Antarctica, though most genera were recovered in Europe, Asia and South America.[1] They were the most diverse and successful pterosaurs during the Early Cretaceous, but throughout the Late Cretaceous they were replaced by better adapted and more advanced pterosaur species such the pteranodontids and azhdarchoids. The most diverse families of the group, the Ornithocheiridae and Anhangueridae (some authors consider them synonyms), survived until the early Late Cretaceous with Ferrodraco, Ornithocheirus, Cimoliopterus,[2] Lonchodectes and Lonchodraco[3] being some of the last remaining. The Ornithocheiromorpha was defined in 2014 by Andres and colleagues, and they made Ornithocheiromorpha the most inclusive clade containing Ornithocheirus, but not Pteranodon.[4]

| Ornithocheiromorphs | |

|---|---|

| |

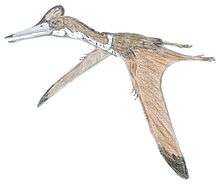

| Reconstructed skeleton of Tropeognathus in the National Museum of Brazil | |

| |

| Skeletal cast of Maaradactylus spielbergi in the Naturalis Biodiversity Center | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Order: | †Pterosauria |

| Suborder: | †Pterodactyloidea |

| Clade: | †Pteranodontoidea |

| Clade: | †Ornithocheiromorpha Andres et al., 2014 |

| Subgroups | |

| |

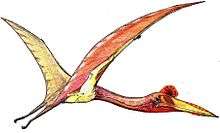

Ornithocheiromorphs are considered to be some of the largest animals to have ever flown. Members of this group are also regarded to have some of the largest pterosaur wingspans, such as the one estimated for the huge Tropeognathus,[5] though still not as large as those estimated for the azhdarchids, which may have reached up to 12 meters (39 ft).[6] When ornithocheiromorphs first appeared, they were initially scavengers, consisting in a more terrestrial setting, but their success had made them the top predators of the skies, as well as the most common type of fish-eating pterosaur throughout the early Late Cretaceous. Some paleontologists also consider ornithocheiromorphs an earlier step of evolution to the pteranodontids, this is due to the similar flying techniques and flight locomotions, as well as their diet, which mainly consisted of fish, and therefore also hunted very similarly.[7] Ornithocheiromorphs also flew like soaring birds, keeping their wings stretched and rarely flapping. The pteranodontids Pteranodon and Geosternbergia[8] are also found to have had this flight technique, resulting in a much more effective way of hunting over the surface of the water, and therefore had more success than the more primitive scavenging istiodactylids.[9]

History of research

Early discoveries

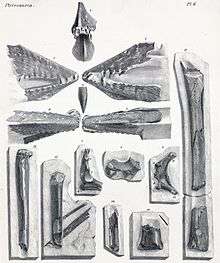

The first specimens of ornithocheiromorphs were unearthed at a chalk pit near Burham in Kent, England. In 1846, British paleontologist James Scott Bowerbank named and described the remains found as Pterodactylus giganteus, as it was common at that time to assign any new described pterosaur species to Pterodactylus.[3] In the same chalk pit as P. giganteus, two other pterosaur species were discovered. The first was named in 1851 by Bowerbank as Pterodactylus cuvieri,[2] in honor of the prominent German naturalist and zoologist Georges Cuvier, while the second was described in the same year by British paleontologist Sir Richard Owen as Pterodactylus compressirostris.[10]

In 1861, further pterosaur specimens were found in the UK, and were given the new species Pterodactylus simus by Owen.[11] British paleontologist Harry Govier Seeley then created the new genus Ornithocheirus for the new species in the same year, the generic name translating as "bird hand" is due to the notion of the time that pterosaurs were the ancestors of modern birds. In 1869, Seeley reassigned Pterodactylus cuvieri into Ptenodactylus cuvieri, but in 1870, Seeley had realized that the generic name Ptenodactylus had been considered a nomen nudum, and therefore reassigned the species into Ornithocheirus cuvieri. Between 1869 and 1870, Seeley reassigned various species of pterosaurs, including P. cuvieri into newly named species of Ornithocheirus, therefore 27 in total.[12][13]

Richard Owen wasn't pleased when Seeley published his conclusions in his 1870 book The Ornithosauria, and he therefore considered the name Ornithocheirus to be inappropriate. In 1874, Owen created two new genera, Coloborhynchus, meaning "maimed beak" and Criorhynchus, meaning "ram beak". While Coloborhynchus consisted in a totally new type species, C. clavirostris, as well as two other species reassigned from Ornithocheirus, Criorhynchus consisted entirely of former Ornithocheirus species, including the type species, O. simus, which was later reassigned by Owen as Criorhynchus simus, as well as 5 other species. In the same year, Owen also reassigned O. cuvieri into Coloborhynchus cuvieri.[14] Seeley later disagreed and didn't accept Owen's position, and he therefore assigned Ornithocheirus simus as the type species of Ornithocheirus in 1881. Seeley had also named a new separate species called O. bunzeli in the same year.[15]

In 1914, English paleontologist Reginald Walter Hooley kept the name Ornithocheirus, but created two new genera: Lonchodectes, meaning "lance biter", and Amblydectes, meaning "blunt biter". This classification was rarely applied at the time, though.[16] The species Pterodactylus compressirostris was formerly transferred to Ornithocheirus in 1870 by Seeley, but it became the type species of Lonchodectes in Hooley's 1914 review of Ornithocheirus.[13] Confusingly, this species was also long regarded, incorrectly, as the type species of Ornithocheirus.[16]

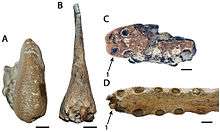

In 2013, Brazilian paleontologists Taissa Rodrigues & Alexander Kellner made a deeper analysis on the species Pterodactylus cuvieri. In the analysis, they stated that it needed a separate genus, and assigning it to Ornithocheirus was inappropriate, therefore, they created the new genus called Cimoliopterus, with the new resulting combination Cimoliopterus cuvieri, though its type species still remains as P. cuvieri. The generic name Cimoliopterus combines Κιμωλία, Kimolia (meaning "chalk" in New Greek), in reference to the white clay of the island Kimolos, and the Latinised Greek word πτερόν, pteron, which means "wing". In the same year, Rodrigues & Kellner also reviewed the species Pterodactylus giganteus, and reassigned it to Lonchodectes, resulting in a Lonchodectes giganteus. Both paleontologists later concluded that the genus Lonchodectes and its type species L. compressirostris were nomina dubia, and therefore L. giganteus needed a new separate genus. Rodrigues & Kellner created the new genus Lonchodraco, and reassigned L. giganteus from Lonchodectes into the new genus, resulting in a new combination called Lonchodraco giganteus. The generic name combines Greek λόγχη, lonchē (meaning "lance"), with Latin draco, meaning "dragon".[17]

In 1887, Seeley had described new fossil remains from the Isle of Wight, an island off the coast of southern England. He thought it belonged to some kind of bird-like creature, which he named it Ornithodesmus cluniculus.[18] John Whitaker Hulke suggested later that year that Ornithodesmus was a pterosaur, finding it similar to fossils that he had seen before, but Seeley disagreed.[19] Seeley also reported another specimen found on the same site, which was then acquired in the British Museum in 1882. The specimen had been assigned to Ornithocheirus nobilis by Richard Lydekker in 1888, but Seeley considered it another species of Ornithodesmus, which he now considered a species of pterosaur instead of a bird. In 1901, Seeley named the new species as O. latidens, which means "wide tooth".[20]

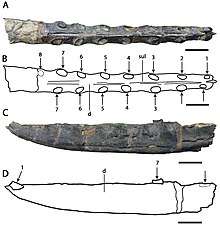

Reginald Hooley later described two more specimens of O. latidens in 1913, which were collected in 1904 from the sea after a rockfall near Atherfield Point on the Isle of Wight. The first of the specimens was collected, and consisted of a skull, neck and trunk vertebrae, a shoulder blade, an ischium, and parts of the forelimbs. The second specimen was collected in just one block, and it includes parts of the forelimbs and pectoral girdle. These two specimens represent the most complete remains of Cretaceous pterosaurs found in England. Hooley also discussed O. latidens in detail, which led Ornithodesmus to be placed within its own family, Ornithodesmidae.[21] But then his article ended with a discussion wherein it was noted that the palaeontologist Charles William Andrews had expressed doubts as to whether O. latidens belonged in the genus Ornithodesmus, as the vertebrae of the specimen that genus was based on differed markedly from those of Hooley's specimen. The American palaeontologist Samuel W. Williston subsequently reviewed Hooley's article, disagreeing with some of his conclusions about the anatomy and classification of the animal.[22] After Hooley's monograph, little was written about the animal for the rest of the 20th century, and no similar pterosaurs were found for decades.[23]

In 1993 however, the British palaeontologists Stafford C. Howse and Andrew C. Milner concluded that the holotype sacrum and only specimen of O. cluniculus didn't belong to a pterosaur, but instead to a maniraptoran theropod dinosaur. They also pointed out that no detailed attempts had been made to compare the sacrum of O. cluniculus with those of pterosaurs, and that O. latidens had in effect been treated as the type species of the genus Ornithodesmus. Now as a definite species of pterosaur, "O." latidens thus required a new genus name.[24] Howse, Milner, and David Martill in 2001, moved "O." latidens to a new genus called Istiodactylus. The generic name means "sail finger", which refers to the wings of large pterosaurs. After moving "O." latidens into Istiodactylus, they had also named a new family called Istiodactylidae, with Istiodactylus as the only member.[25]

Discoveries outside Europe

Other important ornithocheiromorph discoveries include the ornithocheirids Tropeognathus and Anhanguera from the Romualdo Formation in Brazil.[26][27] Tropeognathus was described with its type species, T. mesembrinus in 1987 by German paleontologist Peter Wellnhofer. The generic name is derived from Greek τρόπις, tropis, meaning "keel", and γνάθος, gnathos, meaning "jaw". The specific name is derived from Koine mesembrinos, "of the noontide", simplified as "southern", in reference to the provenance from the Southern hemisphere. The description then led to an enormous taxonomic confusion.[28] In 1989, Brazilian paleontologist Alexander Kellner considered it an Anhanguera mesembrinus,[29] then a Coloborhynchus mesembrinus by Veldmeijer in 1998,[30] and then a Criorhynchus mesembrinus in 2001 by German paleontologist Michael Fastnacht.[31] T. mesembrinus was then considered a junior synonym of Ornithocheirus simus by British paleontologist David Unwin in 2001, but he then proposed an Ornithocheirus mesembrinus in 2003.[32][33] In 2013 however, Taissa Rodrigues and Alexander Kellner concluded that Tropeognathus would be valid again, and containing only T. mesembrinus, the type species.[17]

The discovery of Anhanguera in 1985 made some authors assign several species of Ornithocheirus to the new genus, this is due to the similarities of Anhanguera and Ornithocheirus. One of which was Ornithocheirus cuvieri, formerly known as Pterodactylus cuvieri, was renamed by David Unwin in 2001 as Anhanguera cuvieri, though in 2013 it has been considered a synonym of Cimoliopterus.[32][17] Other species of Anhanguera include A. piscator, which is known from a nearly-complete skeleton, and was once proposed to belong to the genus Coloborhynchus, but it has recently been placed back into Anhanguera by Andres and Myers (2013).[34][35] Another species which is also known from a complete skeleton is A. spielbergi, which was also originally considered as a species of Coloborhynchus in 2003, though in 2018, it has been reassigned to the genus Maaradactylus, specifically to its own species, M. spielbergi.[36][37]

A discovery in Asia, specifically northwestern China, was reported in 2006. The lake sediments allowed an exceptional preservation of fossils, and therefore paleontologists Qiu Zhanxiang and Wang Banyue started official excavations. Part of the findings consisted of dense concentrations of pterosaur bones, associated with soft tissues and eggs. The site represented a nesting colony that storm floods had covered with mud. Dozens of individuals could be secured to run into the many hundreds.[38] In 2014, a new species was named and described: Hamipterus tianshanensis. It was named by Wang Xiaolin, Alexander Kellner, Jiang Shunxing, Wang Qiang, Ma Yingxia, Yahefujiang Paidoula, Cheng Xin, Taissa Rodrigues, Meng Xi, Zhang Jialiang, Li Ning, and Zhou Zhonghe. The generic name Hamipterus combines that of the Hami region, with the word pteron, meaning "wing", and the specific name refers to the provenance from the Tian Shan, a mountain range.[38] These findings represented an impressively large concentration of pterosaur fossils, and together with the Pterodaustro[39] nesting colonies in Argentina, both are regarded as the most diverse fossil concentrations of pterosaurs ever known.[40]

Description

Size

Ornithocheiromorphs were large pterosaurs, with wingspans normally ranging between 3 to 6 meters (9.8 to 19.7 ft).[6] Istiodactylus for example, had a wingspan ranging from 4.3 to 5 meters (14 to 16 ft), with the most complete known skull estimated to have been about 45 centimeters (1.48 ft) in length, based on a long-lost fragment of its jaw reported in 2012.[9] Though its jaws measured only 28.5 centimeters (11.2 in), which was less than 80 percent of the skull's length.[23] Ornithocheirids were typically larger than others of the group and were more successful within the food chain rather than other ornithocheiromorphs, one reason is because of their large size, Ornithocheirus itself had a wingspan measuring 4.5 to 6.1 meters (15 to 20 ft). Other ornithocheirids were also regarded with similar wingspans, though the largest is probably Tropeognathus mesembrinus, with a wingspan exceeding 7 meters (23 ft), and 8.2 meters (27 ft) as the maximum estimate.[5] Another genus which was impresively large is Coloborhynchus, with a total skull length that could have been up to 75 centimeters (2.46 ft), leading to an estimated wingspan of 7 meters (23 ft).[41] However, this species may belong to a different genus.[17] One of the smaller genera includes the boreopterid Boreopterus, which is estimated to have a wingspan of around 1.45 meters (4.8 ft), but some paleontologists consider it a synonym of Zhenyuanopterus, in this case measuring around 3.5 to 4 meters (11 to 13 ft) in length.[42][43]

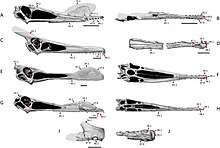

Skull and crests

Most ornithocheirids bore distinctive convex "keeled" crests on their snout and underside of their mandible, this was well developed in several genera such as Tropeognathus.[44] The similar Anhanguera possessed jaws that were tapered in width, but expanded into a broad, spoon-shaped rosette at the tip. The jaws are distinguished from its relatives by several differences in the crest and teeth: unlike its close relatives Coloborhynchus and Ornithocheirus, the crest on the upper jaw of Anhanguera didn't begin at the tip of the snout, therefore, it was set farther back on the skull.[45] Several ornithocheiromorphs such as the basal Lonchodectes, had long jaws similar to the ornithocheirids, but were mostly thinner and more elongated. Lonchodectes had many short teeth, and its jaws were compressed vertically. Comparisons between ornithocheirids such as Ornithocheirus led to a conclusion that it had a relatively narrower premaxilla compared to related genera like Coloborhynchus and Anhanguera.[31][46]

Some basal anhanguerians like Cearadactylus had its first preparations with many serious mistakes: the front of the snout and the lower jaws were confused leading to a reconstruction in which the anterior part of the head was upside down.[47] Some of the teeth were extensively restored and enlarged until the wider front of the jaws showed very large and robust teeth projecting outwards. With this arrangement, the maxilla was kinked, and its interlocking teeth suggested that Cearadactylus had a piscivourous diet, allowing the animal to keep hold of slippery fish.[7] Cearadactylus was somewhat similar to ornithocheirids like Coloborhynchus, but it lacked the "keeled" crest on its snout, and therefore it was suggested to be a more basal form of ornithocheiromorph pterosaur.[48][49] Another smaller genus similar to Cearadactylus is Guidraco. Its holotype skull has a length of 38 centimeters (15 in), which makes it smaller than other genera. The skull is very elongated however, and a hollow profile is seen, but not very pointed, as the upper edge and the line of the jaw run nearly parallel over most of their length.[50]

Even though most ornithocheiromorphs didn't have a cranial crest like the closely related pteranodontids, there were some exceptions, this included Caulkicephalus and Ludodactylus.[51] While Ludodactylus is suggested to be a more basal member of the group, Caulkicephalus is more similar to ornithocheirids.[52] This is due to its rounded snout, very similar to that of Ornithocheirus and therefore it was placed within Ornithocheiridae. Caulkicephalus was also a large pterosaur, with wingspan estimates of around 5 meters (16 ft).[52]

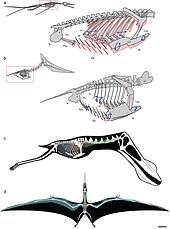

Wings

Most pterosaurs of this group had extensive wing-membranes, which were distended by a long wing-finger and would have been covered in hair-like pycnofibres.[53] Like the modern-day albatross, ornithocheiromorphs also had a high aspect ratio and low wing loadings, though this is typically in the larger and more advanced genera. Wing remains of the istiodactylid Nurhachius have been compared to those of modern soaring birds, which fly with little flapping, and may have been ideal for low-energy soaring, which is necessary when searching for carrion or fish.[54] The wings of istiodactylids also seem to have been shorter compared to the fish-eating ornithocheirids, and unlike them, which were more suited for taking off and landing, istiodactylids may have preferred a more terrestrial setting. This is also seen in many inland soaring birds, which have a lower aspect ratio compared those that soar over the ocean. Huge genera such as Tropeognathus and Ornithocheirus are considered to have flown similar to modern-day albatrosses, which consisted on travelling very long distances and rarely flapping. This technique is mostly seen in later pterosaur locomotion, such as the related and mentioned pteranodontids, though not so common in the larger azhdarchids such as Hatzegopteryx and Quetzalcoatlus.[8][6]

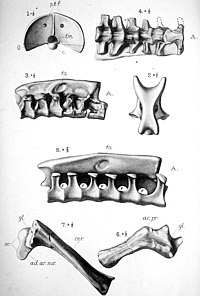

Shoulder girdle

Ornithocheiromorphs had shoulder girdles of strong structure, which transferred the forces of a rarely flapping flight to the thorax. The shoulder girdle was probably covered by thick muscle layers, with the upper bone (shoulder blade) resulting in some kind of straight bar.[55] The shoulder blade was connected to a lower bone called the coracoid, which is relatively long in most ornithocheiromorphs. In the more advanced species, the shoulder is combined whole, with the scapulocoracoid, being almost vertically oriented, meaning that it fitted into a recess in the side of the notarium, while the coracoid likewise connected to the breastbone. Some species also had the shoulder joint moved from the shoulder blade to the coracoid. The breastbone is somewhat wide, and was formed by fused paired sterna. At its rear, a row of belly ribs or gastralia was present, covering the entire belly.[56] To the front of the breastbone, a long point called the cristospina, jutted obliquely upwards, and the rear edge of the breastbone was the deepest point of the thorax. The absence of clavicles or interclavicles had made paleontologists wonder if pterosaurs evolved in different ways than other archosaurs.[57][56]

Vertebrae

The vertebral column of ornithocheiromorphs was heavily pneumatized by an extensive system of air sacs, leaving prominent pneumatic foraminae.[58] The neck of ornithocheiromorphs was typically relatively long and robust, being longer than the torso in some derived clades.[59] The neural spines of ornithocheiromorph cervical vertebrae were generally tall and spikelike.[50][45] In some genera such as Tropeognathus and Istiodactylus, up to six dorsal vertebrae are fused into a notarium.[60] In some genera such as Anhanguera, four to seven sacral vertebrae are fused into a synsacrum.[45] The tail is not well-known in ornithocheiromorphs, however. Zhenyuanopterus, which is known for having 13 caudal vertebrae, formed one of the longest tails of any pterodactyloid.[42] Anhanguera, another well-known genus, had a shorter tail, with broad caudal vertebrae that bore a "duplex" cross-section similar to Pteranodon.[45]

Pelvic structure

The pelvis of ornithocheiromorphs was of moderate size compared to the body as a whole, similar to other ornithocheiroids. The three pelvic bones were often fused, as seen in many species such as Anhanguera santanae, the ilium was long and low, and its front and rear blades projected horizontally beyond the edges of the lower pelvic bones.[61] Despite the structure length, the processes of these rod-like forms indicate that the hindlimb muscles attached to them were limited in strength.[62] The pubic bone was fused with the broad ischium into an ischiopubic blade, resulting in a narrow build. Sometimes, the blades of both sides were fused, closing the pelvis from below and forming the pelvic canal. The front of the pubic bones was also articulated with a unique structure, resulting in a pair of prepubic bones within. This formed a cusp covering the rear belly, and was located between the pelvis and the belly ribs. The hip joint of ornithocheiromorphs was not perforated and allowed considerable mobility to the leg, and suggests that it was vertical, as therefore had a function in breathing, compensating the relative rigidity of the chest cavity.[63][61]

Hindlimbs

The hindlimbs of ornithocheiromorphs were strongly built, yet relative to their wingspans, smaller than those of birds in terms of hindlimb-to-wingspan ratio. The hindlimbs were long in comparison to the torso length, and the thighbone was rather straight, with the head making only a small angle with the shaft.[64][63] This implied the legs not being held vertically below the body, but were somewhat sprawling within.[64] A tibiotarsus is mostly seen in many ornithocheiromorphs, this consisted on the shinbone (tibia) being fused with the upper ankle bones, resulting in a longer structure than the thighbone, which could attain a vertical position when walking.[65] Most of the toes of ornithocheiromorphs were long, though compared to earlier forms of pterosaurs, they were less robust, and were also connected to the ankle in a higher position than the other metatarsals. Often curved, the mobile clawless fifth toe consisted of two phalanges, this is seen some specimens, which showed membranes between the toes, and was concluded that this allowed them to function as flight control surfaces.[66]

Classification

Several studies show that ornithocheiromorphs were less derived than the toothless pteranodontids such as Pteranodon, and based on the different evolutionary changes, they therefore need to be grouped in a different clade than Pteranodon, though still within Pteranodontoidea.[67] Early and controversial morphological comparisons of ornithocheiromorphs were made in 1913 by Hooley, with Istiodactylus as the sole member of Istiodactylidae.[21][25] In the comparisons, different species were assigned within Ornithocheiridae, such as Coloborhynchus,[41] but the data recovered from several ornithocheiromorphs in that time was limited, so specific placements were scarce. During the first phylogenetic analyses of Istiodactylus, it was considered to be some sort of rhamphorhynchid pterosaur, similar to Scaphognathus or maybe even the earlier Dimorphodon, but later studies show that it was closer related to the short-tailed pterodactyloids.[33] With the discoveries of Tropeognathus and Anhanguera in the 1980s, it made more sense to group Istiodactylus with Ornithocheiridae, due to their very similar aspects.[44] This also added to the reassigning of other istiodactylids and other similar toothed pterosaurs within Ornithocheiridae, which then led to debates between two schools of pterosaur classification. In 2003, David Unwin considered Istiodactylidae to group with the toothless Pteranodontidae, though still within Ornithocheiroidea,[33] but Alexander Kellner grouped it with the toothed Ornithocheiridae instead, resulting in a more understandable change of evolution between the two toothed families.[44][49]

Studies on Lonchodectes and its family, Lonchodectidae (which only consisted of Lonchodectes), has since been classified to many different clades, including Ctenochasmatoidea and Azhdarchoidea. More recent reclassifications show that Lonchodectidae was instead a closer relative of the ornithocheirids, but was given a basal placement because of uncertain fossil structures and other features seen uniquely in Lonchodectes. The genus Prejanopterus was formerly considered a lonchodectid, but its placement is very uncertain, and some authors just consider it a basal archaeopterodactyloid.[68] Another genus, Lonchodraco, is also in a dubious placement, Rodrigues & Kellner made a family called Lonchodraconidae containing only Lonchodraco, but it was then reclassified to Lonchodectidae along with Lonchodectes, and therefore synonymizing the two families.[17]

Brian Andres and colleagues found the families Istiodactylidae, Ornithocheiridae and Anhangueridae to form a group in 2014, which he called Lanceodontia, and consists of the more advanced ornithocheiromorphs. The clade however, excludes the more poorly known family Lonchodectidae, even though members of the family had previously been seen as some of the most derived forms of toothed pterosaurs.[4]

Phylogeny

Below is a cladogram showing the results of a phylogenetic analysis presented by Andres et al., 2014. In the analysis, they placed the former istiodactylid Hongshanopterus as a basal member, and also found the family Boreopteridae to belong within Anhangueria, though placed in a more basal position.[4][69]

| Pteranodontoidea |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In 2019, new species of ornithocheiromorphs were found, and the former species Ornithocheirus wiedenrothi was renamed as Targaryendraco wiedenrothi.[70] The discovery of Iberodactylus[71] in Spain also made paleontologists reclassify the genus Hamipterus[38] in a newly named family called Hamipteridae. The former ornithocheirid Cimoliopterus[2] was also reclassified as well, and it is currently grouped with Aetodactylus[72] and Camposipterus in the newly named clade Targaryendraconia,[70] specificaly to its own family, the Cimoliopteridae. The former istiodactylid Haopterus was reclassified due to the discovery of Mimodactylus, and it's placed as the sister taxon of it in a new family called Mimodactylidae.[73]

The cladogram below is a topology recovered by Pêgas et al. (2019). In the analyses, they found Ornithocheiromorpha to be synonymous with Lanceodontia, and recovered Ornithocheirae as the more inclusive group containing Ornithocheirus, Anhangueria and Targaryendraconia. They also reassigned most of the ornithocheirid genera into the family Anhangueridae, which resulted in a basal position for Ornithocheirus within Ornithocheirae.[70]

Paleobiology

Diet and feeding

Ornithocheiromorphs were originally regarded as piscivorous creatures, feeding mainly on small and mid-sized fish.[7] Some paleontologists even suggested details on how these pterosaurs caught fish, some of which included dipping their beaks close to the water for prey.[7] Hooley for example, found that the beak of the well known Istiodactylus was similar to those of birds such as herons, storks, and skimmers, and suggested that Istiodactylus probably fed on fish, this was mainly based on his 1913 jaw reconstruction of the animal.[21] In 1991, Peter Wellnhofer compared the jaw endings of Istiodactylus with those of a duck, but he then noticed that it wasn't a "duck-billed pterosaur" or anything similar, even though it was popularly called that way.[74] Other diet suggestions for Istiodactylus were mostly based on the broad snout remains, as well as the very distinctive teeth; leading to the thought of a more terrestrial life and hunting methods, which is far different from the lifestyle of later genera such as the huge Tropeognathus. This conclusion was later followed by Howse and colleagues suggesting that the strong, yet bizarre teeth of Istiodactylus were more suited for scavenging carcasses rather than catching fish, this led the idea of a different feeding technique, which consisted in bitting and twisting the skull to remove large chunks out of the carcass, very different from the initial suggestions of how early ornithocheiromorphs fed. Witton in 2012 found that the teeth of Istiodactylus were unlike the recurved and enlarged teeth seen in the more derived ornithocheirids such as Ornithocheirus, he instead pointed out that it was more "razor-edged" and better suited for carrion rather than fish.[9]

Another ornithocheiromorph that possesed similar features to Istiodactylus is Liaoxipterus, which is known from a skull with several unique traits, including numerous peg-like teeth. The shape of its teeth indicated that Liaoxipterus was a possible insectivore,[75] though this conclusion isn't considered entirely accurate.[76] Liaoxipterus was also smaller in size compared to Istiodactylus and other ornithocheiromorphs, this is perhaps an indication that the more primitive members of this group (istiodactylids in this case) were smaller compared to more derived and advanced families such as the lonchodectids, ornithocheirids and targaryendraconians. This can also be seen in the size comparison between ornithocheirids and istiodactylids, with the wingspan of Tropeognathus for example, measuring almost double that of Istiodactylus.[26][9]

Ornithocheirids like Tropeognathus and Coloborhynchus are considered to be fish-eaters, and had longer and sharper teeth compared to the more rounded teeth of Istiodactylus, though this is still sometimes disputed.[7] Another difference that can be seen in more primitive ornithocheiromorphs their eyes being proportionally smaller compared to the assumed predatory and more advanced ornithocheirids, this again adds to the fact that the more primitive groups (istiodactylids) were most likely scavengers, and later got more successful within the food chain, leading the later, more advanced groups (ornithocheirids and lonchodectids) to be the dominant fish hunters during the early Late Cretaceous.[7][77]

Teeth enamels

A 2017 study confirmed that most ornithocheirids were fish-eaters, though in a deeper analysis, paleontologists found carbon isotopes within several teeth, and later compared the enamel values of the ornithocheirid teeth between the aquatic and terrestrial consumers near the fossil site.[7] Pterosaur enamels from the Twin Mountains Formation were shown with lower enamel values in comparison to the aquatic consumers that lived near, suggesting a more terrestrial diet, this is mostly due to the similarly low enamel values found in carnivorous theropods such as Acrocanthosaurus, which mainly had a terrestrial diet. The enamels found in the Paw Paw Formation however, were described with higher values, in comparison to the nearby terrestrial consumers. Analyzing these enamel remains, paleontologists found out that the values seen were more comparable to the aquatic consumer values rather the terrestrial ones. These analyses are considered a very useful reference to the evolutionary changes between the earlier and later species of ornithocheirids, as well as other ornithocheiromorphs. The diet changes were also taken into account, with earlier genera such as Coloborhynchus having a varied diet, preying partially on fish, while also hunting on land. The later genera such as Uktenadactylus however, fed almost entirely on fish, and rarely hunted on land.[7] This can be demonstrated with the age difference between the Twin Mountains Formation and the Paw Paw Formation. The enamel remains found in the Twin Mountains Formation dated back to the earlier Aptian stage, while the remains found in the Paw Paw Formation dated back to the later Albian stage, resulting in a slight diet transition between more primitive and more derived genera.[7]

Respiration

Pterosaur studies in 2009 showed that several pterosaurs, including ornithocheiromorphs, had a lung-and-air-sac system and a precisely controlled skeletal breathing pump, which supports a flow-through pulmonary ventilation model in pterosaurs, analogous to that of birds. This breathing method is also seen is carnivorous dinosaurs such as Aerosteon, but there are currently no studies showing its relationships with pterosaurs.[78] A subcutaneous air sac system is present in at least some species of pterodactyloids, and this technique would have given a further reduced density to the living animal when breathing.[79] Similar to modern crocodilians, many ornithocheiromorph genera appeared to have had some kind of hepatic piston, regarding their shoulder-pectoral girdles, which were suggested to be too inflexible to move the sternum. This can also be seen in modern-day birds, which similarly possess strong gastralia, and therefore paleontologists erect the idea that their respiratory system had characteristics comparable to primitive archosaurs.[80]

Locomotion and flight

Ornithocheiromorphs, like other pterosaurs, are considered to have been skilled fliers as well as swift at moving on the ground. Footprints from several species show that most pterosaurs did not sprawl their limbs to a large degree, as in modern reptiles, but rather held the limbs relatively erect when walking, like dinosaurs. While footprints are yet to be known, it is likely that ornithocheiromorphs also walked erect.[66] Compared to other earlier pterosaurs such as rhamphorhynchids, ornithocheiromorphs had unusually uneven limb proportions, with the forelimbs resulting in a much longer scale compared to the hind limbs. Their close relatives, the pteranodontids, were also found with similar features, though they more likely flew like modern-day albatrosses rather than anything else. Paleontologists also suggest that they most likely spend long stretches of time sea fishing, travelling very long distances without flapping while at the same time flying close the surface of the water with exploited wind speed, and without the necesity of thermals.[65] This would likely have required them to use unique modes of locomotion compared to other pterosaurs, this can already be seen in earlier evolutions such as Istiodactylus and Nurhachius, with powerful musculature attachments and well-developed pectoral and upper arm bones.[9][54] It is also possible that ornithocheiromorphs ran (but not walked) bipedally, or that they used a hopping gait.[66] Many pterosaur researchers like Mike Habib have noted that the limb proportions of some ornithocheiromorphs such as Anhanguera are consistent with hopping, though the scavenging istiodactylids are probably still the best examples of pterosaurs with a more terrestrial setting.[81][21]

Paleoecology

Ornithocheiromorphs were present since the Early Cretaceous (Valanginian stage), and evolved throughout the rest of the period. Studies on the ornithocheirids Tropeognathus[26] and Anhanguera,[45] suggested that ornithocheiromorphs also expanded their distribution, while also evolving specialized features. The significant adaptions of the ornithocheiromorphs had also made them the top pterosaurs in almost every formation by the early Late Cretaceous, including the ones they were rare in, such as the Blesa Formation in Spain, where only Iberodactylus has been found.[71]

Even though the ornithocheiromorphs were discovered worldwide, most of them were concentrated in specific places. One specific fossil site containing an impresive number of pterosaurs is the Romualdo Formation, a diverse Lagerstätte in the larger geologic group called the Santana Group (sometimes called the Santana Formation), which is located in the Araripe Basin of northeastern Brazil, and dates back 111-108 million years ago during the Albian stage of the Early Cretaceous. The formation includes many species of Anhanguera,[45] several fossil remains of basal ornithocheiromorphs, including Brasileodactylus, Cearadactylus and Unwindia, as well as the ornithocheirids Tropeognathus,[26] Coloborhynchus, Maaradactylus, Araripesaurus and Barbosania.[31] These pterosaur genera were just some of the many recovered from the site, which also include the thalassodromids Tupuxuara and Thalassodromeus,[82] as well as the tapejarid Tapejara,[83] the basal pteranodontoid Santanadactylus and the dubious Araripedactylus. Some other creatures from the formation include the theropods Irritator, Mirischia and Santanaraptor, and the crocodylomorph Araripesuchus. The formation also includes several turtle remains, with some specimens referring to Santanachelys, Cearachelys and Araripemys.[84] A few fish remains were also found within the Romualdo Formation, some of which were referred to Brannerion, Rhinobatos, Rhacolepis, Tharrhias and Tribodus. The Santana Group also consists of another Lagerstätte called the Crato Formation, which is not as diverse as the Romualdo Formation, but its fossil remains are still considered important.[85] This fossil site underlies the Romualdo Formation, and dates back around 115-113 million years ago during the Aptian stage, meaning that its fossil content is of older age. Similarly, the Crato Formation also contained several species of pterosaurs, including the basal lanceodontians Ludodactylus[51] and Brasileodactylus, as well as the ornithocheirid Arthurdactylus. Other pterosaur genera include the tapejarids Tupandactylus and Aymberedactylus,[83] as well as the chaoyangopterid Lacusovagus. The formation also contains other creatures such as the enantiornithine Cratoavis, the neosuchian Susisuchus, and several species of fish, including Belonostomus, Calamopleurus,[86] Cladocyclus,[87] Dastilbe[88] and Lepidotes.[89] These fish genera were suggested to be prey for the pterosaurs that lived in the formation, but fossil remains are limited, so the subject is still controversial.[7]

Another important fossil site is the Wessex Formation in the Isle of Wight, near the coast of England, which dates back 140-125 million years ago (Berriasian to Barremian stages). The formation doesn't contain many fossil remains of pterosaurs compared to the Romualdo Formation, but it is still a very important site. Fossil remains of the istiodactylid Istiodactylus,[9] the ornithocheirid Caulkicephalus,[52] and the tapejarid Wightia were found.[90] The formation is also known for several theropods, including the spinosaurid Baryonyx, the tyrannosauroid Eotyrannus, the dromaeosaurid Ornithodesmus, the compsognathid Aristosuchus as well as the allosauroid Neovenator.[91][92] Differents types of herbivorous dinosaurs like Iguanodon, Polacanthus, Ornithopsis, Mantellisaurus and Hypsilophodon were also found within the fossil site.[93][94] Some other animals from the formation include the neosuchian Bernissartia, sea turtles such as Helochelydra and Brodiechelys, the cartilaginous fish Hybodus, ray-finned fishes such as Belonostomus, Caturus, Lepidotes and Scheenstia, as well as the mammals Eobaatar, Loxaulax and Yaverlestes.[89][95][96]

A few fossils reported from the Toolebuc Formation and Winton Formation are believed to be from some of the most derived ornithocheiromorphs, due to the age of the fossil remains, which dated back to the Albian and Cenomanian stages of the Cretaceous, and some are even believed to belong to the Turonian stage. The Toolebuc Formation includes several remains of ornithocheiromorphs which are now referred to the genera Aussiedraco and Mythunga.[97][98] The formation also includes several herbivorous dinosaurs such as the ornithopod Muttaburrasaurus and the ankylosaur Kunbarrasaurus.[99][100] Fossil remains of marine animals were also uncovered within the fossil site, and some specimens of which belong to the ichthyosaur Platypterygius, the pliosaurid Kronosaurus and the elasmosaurid Eromangasaurus.[101] Turtle remains from turtles that were proposed to be prey for pterosaurs were also found within the Toolebuc Formation, this included the genera Bouliachelys, Cratochelone and Notochelone.[7] The Winton Formation consisted on a more terrestrial environment, containing several sauropod dinosaurs like Austrosaurus, Diamantinasaurus, Savannasaurus and Wintonotitan as well as large carnivorous dinosaurs such as Australovenator[102] and crocodylomorphs like Isisfordia. The formation's only pterosaur is the derived ornithocheirid Ferrodraco,[103] which is also considered as one of the last ornithocheiromorphs, and a close relative of Mythunga.[98] Although these two Australian formations contain some of the most derived members of this group, some specimens from the Chalk Formation in Kent, England probably had a similar or younger age. These fossils dated back around 94 million years ago, and belonged to the lonchodectid Lonchodraco, and the former ornithocheirid Cimoliopterus,[2] which is now reclassified as a targaryendraconian.[70] Lonchodraco, formerly known as Pterodactylus giganteus,[3] lived throughout the late Cenomanian and early Turonian stages, and Cimoliopterus is also considered to be from the same time. Lonchodraco, along with Lonchodectes, are both classified as basal members of Ornithocheiromorpha, due to complex taxonomy issues, despite their young ages.[104]

See also

References

- Barrett, P. M., Butler, R. J., Edwards, N. P., & Milner, A. R. (2008). Pterosaur distribution in time and space: an atlas. Zitteliana: 61-107.

- Bowerbank, J.S. (1851). "On the pterodactyles of the Chalk Formation". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London. 19: 14–20. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1851.tb01125.x.

- Bowerbank, J.S. (1846). "On a new species of pterodactyl found in the Upper Chalk of Kent (Pterodactylus giganteus)". Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London. 2 (1–2): 7–9. doi:10.1144/gsl.jgs.1846.002.01-02.05.

- Andres, B.; Clark, J.; Xu, X. (2014). "The Earliest Pterodactyloid and the Origin of the Group". Current Biology. 24 (9): 1011–6. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2014.03.030. PMID 24768054.

- Kellner, A. W. A.; Campos, D. A.; Sayão, J. M.; Saraiva, A. N. A. F.; Rodrigues, T.; Oliveira, G.; Cruz, L. A.; Costa, F. R.; Silva, H. P.; Ferreira, J. S. (2013). "The largest flying reptile from Gondwana: A new specimen of Tropeognathus cf. T. Mesembrinus Wellnhofer, 1987 (Pterodactyloidea, Anhangueridae) and other large pterosaurs from the Romualdo Formation, Lower Cretaceous, Brazil". Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências. 85 (1): 113–135. doi:10.1590/S0001-37652013000100009. PMID 23538956.

- Witton, M.P., Martill, D.M. and Loveridge, R.F. (2010). "Clipping the Wings of Giant Pterosaurs: Comments on Wingspan Estimations and Diversity." Acta Geoscientica Sinica, 31 Supp.1: 79–81

- "Abstract: DIET OF ORNITHOCHEIROID PTEROSAURS INFERRED FROM STABLE CARBON ISOTOPE ANALYSIS OF TOOTH ENAMEL (GSA Annual Meeting in Seattle, Washington, USA - 2017)". gsa.confex.com.

- Martin-Silverstone, E., Glasier, J., Acorn, J., Mohr, S., and Currie, P. 2017. Reassesment of Dawndraco kanzai Kellner, 2010 and reassignment of the type specimen to Pteranodon sternbergi Harksen, 1966. Vertebrate Anatomy Morphology Palaeontology, 3:47-59. doi:10.18435/B5059J

- Witton, M. P. (2012). "New Insights into the Skull of Istiodactylus latidens (Ornithocheiroidea, Pterodactyloidea)". PLOS ONE. 7 (3): e33170. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...733170W. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0033170. PMC 3310040. PMID 22470442.

- Owen, R. (1851). Monograph on the fossil Reptilia of the Cretaceous Formations. The Palaeontographical Society 5(11):1-118.

- Martill, D.M. (2010). "The early history of pterosaur discovery in Great Britain". Geological Society of London, Special Publications. 343 (1): 287–311.

- Seeley, H.G., 1869, Index to the fossil remains of Aves, Ornithosauria, and Reptilia, from the Secondary System of Strata, arranged in the Woodwardian Museum of the University of Cambridge. St. John's College, Cambridge 8: 143. doi:10.1080/00222937008696143

- Seeley, H.G. (1870). The Ornithosauria: an Elementary Study of the Bones of Pterodactyles. Cambridge. p. 113.

- Owen, R. 1874, Monograph on the fossil Reptilia of the Mesozoic Formations. Palaeontographical Society, London, 14 pp

- Seeley, H. G. (1881). "The Reptile Fauna of the Gosau Formation preserved in the Geological Museum of the University of Vienna". Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society. 37 (1): 620–706. doi:10.1144/GSL.JGS.1881.037.01-04.49.

- Hooley, Reginald Walter (1914). "On the Ornithosaurian genus Ornithocheirus, with a review of the specimens from the Cambridge Greensand in the Sedgwick Museum, Cambridge". Annals and Magazine of Natural History. 13 (78): 529–557. doi:10.1080/00222931408693521. ISSN 0374-5481.

- Rodrigues, T.; Kellner, A. (2013). "Taxonomic review of the Ornithocheirus complex (Pterosauria) from the Cretaceous of England". ZooKeys (308): 1–112. doi:10.3897/zookeys.308.5559. PMC 3689139. PMID 23794925.

- Seeley, H. G. (1887). "On a sacrum apparently indicating a new type of bird, Ornithodesmus cluniculus Seeley from the Wealden of Brook". Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London. 43 (1–4): 206–211. doi:10.1144/GSL.JGS.1887.043.01-04.19.

- Seeley, H. G. (1887). "On Patricosaurus merocratus, Seeley, a lizard from the Cambridge Greensand, preserved in the Woodwardian Museum of the University of Cambridge". Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London. 43 (1–4): 219–220. doi:10.1144/gsl.jgs.1887.043.01-04.21.

- Seeley, H. G. (2015) [1901]. Dragons of the Air: an Account of Extinct Flying Reptiles. New York: D. Appleton & Co. pp. 173–175. ISBN 978-1440084942.

- Hooley, R. W. (1913). "On the skeleton of Ornithodesmus latidens; an ornithosaur from the Wealden Shales of Atherfield (Isle of Wight)". Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society. 69 (1–4): 372–422. doi:10.1144/GSL.JGS.1913.069.01-04.23.

- Wllliston, S. W. (1913). "Reviews: the skeleton of Ornithodesmus latidens". The Journal of Geology. 21 (8): 754–756. Bibcode:1913JG.....21..754W. doi:10.1086/622124. JSTOR 30058408.

- Witton 2013, pp. 143–151.

- Howse, S. C. B.; Milner, A. R. (1993). "Ornithodesmus – a maniraptoran theropod dinosaur from the Lower Cretaceous of the Isle of Wight, England". Palaeontology. 36: 425–437.

- Howse, S. C. B.; Milner, A. R.; Martill, D. M. (2001). "Pterosaurs". In Martill, D. M.; Naish, D. (eds.). Dinosaurs of the Isle of Wight. Guide 10; Field Guides to Fossils. London: The Palaeontological Association. pp. 324–335. ISBN 978-0-901702-72-2.

- Peter Wellnhofer (1987). ""New crested pterosaurs from the Lower Cretaceous of Brazil"" (PDF). Mitteilungen der Bayerischen Staatssammlung für Paläontologie und historische Geologie. 27: 175–186.

- Campos, D. de A., and Kellner, A. W. (1985). "Um novo exemplar de Anhanguera blittersdorffi (Reptilia, Pterosauria) da formação Santana, Cretaceo Inferior do Nordeste do Brasil." In Congresso Brasileiro de Paleontologia, Rio de Janeiro, Resumos, p. 13.

- Wellnhofer, P. (1987). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Pterosaurs. New York: Barnes and Noble Books. pp. 124. ISBN 0-7607-0154-7.

- Kellner, A.W.A. (1989). "A new Edentate Pterosaur of the lower Cretaceous from the Araripe Basin, Northeast Brazil". Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciencias. 61: 439–446.

- Veldmeijer, A.J. "Pterosaurs from the Lower Cretaceous of Brazil in the Stuttgart Collection". Geoscience and Engineering. 327: 1–27.

- Fastnacht, M (2001). "First record of Coloborhynchus (Pterosauria) from the Santana Formation (Lower Cretaceous) of the Chapada do Araripe of Brazil". Paläontologische Zeitschrift. 75: 23–36. doi:10.1007/bf03022595.

- Unwin, D.M., 2001, "An overview of the pterosaur assemblage from the Cambridge Greensand (Cretaceous) of Eastern England", Mitteilungen aus dem Museum für Naturkunde in Berlin, Geowissenschaftliche Reihe 4: 189–221

- Unwin, D. M. (2003). "On the phylogeny and evolutionary history of pterosaurs". Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 217 (1): 139–190. Bibcode:2003GSLSP.217..139U. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.924.5957. doi:10.1144/GSL.SP.2003.217.01.11.

- Veldmeijer, A. J. (2003). Preliminary description of a skull and wing of a Brazilian Cretaceous (Santana Formation; Aptian-Albian) pterosaur (Pterodactyloidea) in the collection of the AMNH. PalArch’s Journal of Vertebrate Palaeontology 0, 1-14.

- Andres, B.; Myers, T. S. (2013). "Lone Star Pterosaurs". Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. 103 (3–4): 383–398. doi:10.1017/S1755691013000303.

- Pinheiro, F.L.; Rodrigues, Taissa (2017). "Anhanguera taxonomy revisited: is our understanding of Santana Group pterosaur diversity biased by poor biological and stratigraphic control?". PeerJ. 5: e3285. doi:10.7717/peerj.3285. PMC 5420195. PMID 28484676.

- Jacobs, Megan L.; Martill, David M.; Ibrahim, Nizar; Longrich, Nick (2018). "A new species of Coloborhynchus (Pterosauria, Ornithocheiridae) from the mid-Cretaceous of North Africa". Cretaceous Research. 95: 77–88. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2018.10.018. ISSN 0195-6671.

- Xiaolin Wang; Alexander W.A. Kellner; Shunxing Jiang; Qiang Wang; Yingxia Ma; Yahefujiang Paidoula; Xin Cheng; Taissa Rodrigues; Xi Meng; Jialiang Zhang; Ning Li; Zhonghe Zhou (2014). "Sexually dimorphic tridimensionally preserved pterosaurs and their eggs from China". Current Biology. 24 (12): 1323–1330. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2014.04.054. PMID 24909325.

- Grellet-Tinner, G.; Thompson, M.; Fiorelli, L. E.; Argañaraz, E. S.; Codorniú, L.; Hechenleitner, E. M. N. (2014). "The first pterosaur 3-D egg: Implications for Pterodaustro guinazui nesting strategies, an Albian filter feeder pterosaur from central Argentina". Geoscience Frontiers. 5 (6): 759. doi:10.1016/j.gsf.2014.05.002.

- "Pterosaur hatchlings needed their parents, trove of eggs reveals (Update)". phys.org. Retrieved 2020-04-10.

- Martill, D.M. and Unwin, D.M. (2011). "The world's largest toothed pterosaur, NHMUK R481, an incomplete rostrum of Coloborhynchus capito (Seeley 1870) from the Cambridge Greensand of England." Cretaceous Research, (advance online publication). doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2011.09.003

- Lü, J. (2010). "A new boreopterid pterodactyloid pterosaur from the Early Cretaceous Yixian Formation of Liaoning Province, northeastern China". Acta Geologica Sinica. 24 (2): 241–246. doi:10.1111/j.1755-6724.2010.00204.x.

- Teng, F.; Lü, J.; Wei, X.; Hsiao, Y.; Pittman, M. (2014). "New Material of Zhenyuanopterus (Pterosauria) from the Early Cretaceous Yixian Formation of Western Liaoning". Acta Geologica Sinica. 88 (1): 1–5. doi:10.1111/1755-6724.12176.

- Veldmeijer, A.J. (2006). "Toothed pterosaurs from the Santana Formation (Cretaceous; Aptian-Albian) of northeastern Brazil. A reappraisal on the basis of newly described material Archived 2012-03-17 at the Wayback Machine." Tekst. - Proefschrift Universiteit Utrecht.

- Kellner, A.W.A. and Tomida, Y. (2000). "Description of a new species of Anhanguera (Pterodactyloidea) with comments on the pterosaur fauna from the Santana Formation (Aptian–Albian), northeastern Brazil." Tokyo, National Science Museum (National Science Museum Monographs, 17).

- Unwin, D.M. (2006). The Pterosaurs: From Deep Time. Pi Press:New York, p. 273. ISBN 0-13-146308-X.

- Leonardi, G. & Borgomanero, G. (1985). "Cearadactylus atrox nov. gen., nov. sp.: novo Pterosauria (Pterodactyloidea) da Chapada do Araripe, Ceara, Brasil." Resumos dos communicaçoes VIII Congresso bras. de Paleontologia e Stratigrafia, 27: 75–80.

- Rodrigues, T. and Kellner, A.W.A. (2008). "Review of the pterodactyloid pterosaur Coloborhynchus." Pp. 219–228 in: Hone, D.W.E. and Buffetaut, E. (eds), Flugsaurier: pterosaur papers in honour of Peter Wellnhofer. Zitteliana B, 28.

- Kellner, A. W. A. (2003). "Pterosaur phylogeny and comments on the evolutionary history of the group". Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 217 (1): 105–137. Bibcode:2003GSLSP.217..105K. doi:10.1144/GSL.SP.2003.217.01.10.

- Xiaolin Wang; Alexander W. A. Kellner; Shunxing Jiang; Xin Cheng (2012). "New toothed flying reptile from Asia: close similarities between early Cretaceous pterosaur faunas from China and Brazil". Naturwissenschaften. 99 (4): 249–57. doi:10.1007/s00114-012-0889-1. PMID 22354475.

- Frey, E., Martill, D., and Buchy, M. (2003). A new crested ornithocheirid from the Lower Cretaceous of northeastern Brazil and the unusual death of an unusual pterosaur. In: Buffetaut, E., and Mazin, J.-M. (eds.). Evolution and Palaeobiology of Pterosaurs. Geological Society Special Publication 217:56-63. ISBN 1-86239-143-2.

- Steel, L., Martill, D.M., Unwin, D.M. and Winch, J. D. (2005). "A new pterodactyloid pterosaur from the Wessex Formation (Lower Cretaceous) of the Isle of Wight, England". Cretaceous Research. 26 (4): 686–698. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2005.03.005.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Witton 2013, pp. 51–52.

- Zhou X., Pêgas R.V., Leal M.E.C. & Bonde N. 2019. Nurhachius luei, a new istiodactylid pterosaur (Pterosauria, Pterodactyloidea) from the Early Cretaceous Jiufotang Formation of Chaoyang City, Liaoning Province (China) and comments on the Istiodactylidae". PeerJ 7:e7688. {{DOI: 10.7717/peerj.7688}}

- Witton 2013, p. 44.

- Wellnhofer 1991, p. 52.

- Witton 2013, p. 32.

- Buchmann, R.; dos Santos Avilla, L.; Rodrigues, T. (October 25, 2019). "Comparative analysis of the vertebral pneumatization in pterosaurs (Reptilia: Pterosauria) and extant birds (Avialae: Neornithes)". PLoS One. 14 (10): e0224165. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0224165.

- Wellnhofer 1991, p. 54.

- Witton 2013, pp. 158.

- Wellnhofer 1991, p. 55.

- Witton 2013, p. 46.

- Witton 2013, p. 35.

- Wellnhofer 1991, p. 56.

- Padian, K. (1983). "A functional analysis of flying and walking in pterosaurs". Paleobiology. 9 (3): 218–239. doi:10.1017/S009483730000765X.

- Witton, M.P.; Habib, M.B. (2010). "On the Size and Flight Diversity of Giant Pterosaurs, the Use of Birds as Pterosaur Analogues and Comments on Pterosaur Flightlessness". PLOS ONE. 5 (11): e13982. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...513982W. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0013982. PMC 2981443. PMID 21085624.

- Bennett, S. C. (1994). "Taxonomy and systematics of the Late Cretaceous pterosaur Pteranodon (Pterosauria, Pterodactyloidea)", Occasional Papers of the Museum of Natural History, University of Kansas, Lawrence, 169: 1-70

- Averianov, A.O. (2020). "Taxonomy of the Lonchodectidae (Pterosauria, Pterodactyloidea)". Proceedings of the Zoological Institute RAS. 324 (1): 41–55. doi:10.31610/trudyzin/2020.324.1.41.

- Naish, Darren (April 19, 2010). "Zhenyuanopterus, Boreopterus and the Ask A Biologist relaunch". ScienceBlogs. Retrieved May 7, 2019.

- Rodrigo V. Pêgas, Borja Holgado & Maria Eduarda C. Leal (2019) On Targaryendraco wiedenrothi gen. nov. (Pterodactyloidea, Pteranodontoidea, Lanceodontia) and recognition of a new cosmopolitan lineage of Cretaceous toothed pterodactyloids, Historical Biology, doi:10.1080/08912963.2019.1690482

- Borja Holgado, Rodrigo V. Pêgas, José Ignacio Canudo, Josep Fortuny, Taissa Rodrigues, Julio Company & Alexander W.A. Kellner, 2019, "On a new crested pterodactyloid from the Early Cretaceous of the Iberian Peninsula and the radiation of the clade Anhangueria", Scientific Reports 9: 4940. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-41280-4

- Myers, Timothy S. (2010). "A new ornithocheirid pterosaur from the Upper Cretaceous (Cenomanian–Turonian) Eagle Ford Group of Texas" (PDF). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 30 (1): 280–287. doi:10.1080/02724630903413099.

- Kellner, Alexander W. A.; Caldwell, Michael W.; Holgado, Borja; Vecchia, Fabio M. Dalla; Nohra, Roy; Sayão, Juliana M.; Currie, Philip J. (2019). "First complete pterosaur from the Afro-Arabian continent: insight into pterodactyloid diversity". Scientific Reports. 9(1). doi:10.1038/s41598-019-54042-z.

- Wellnhofer, P. (1991). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Pterosaurs. New York: Crescent Books. pp. 114–116. ISBN 978-0-517-03701-0.

- "The Hyoid Apparatus of Liaoxipterus brachycephalus (Pterosauria) and Its Implications for Food-catching Behavior". doi:10.3975/cagsb.2015.03.13. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Jiang S, Li Z, Cheng X, Wang X. (2020). "The first pterosaur basihyal, shedding light on the evolution and function of pterosaur hyoid apparatuses". PeerJ. 8: 292. doi:10.7717/peerj.8292. PMID 31934505.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Jacobs, Megan L.; Martill, David M.; Unwin, David M.; Ibrahim, Nizar; Zouhri, Samir; Longrich, Nicholas R. (2020). "New toothed pterosaurs (Pterosauria: Ornithocheiridae) from the middle Cretaceous Kem Kem beds of Morocco and implications for pterosaur palaeobiogeography and diversity". Cretaceous Research. 110: 104413. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2020.104413. ISSN 0195-6671.

- Sereno, P.C., Martinez,R.N., Wilson, J.A., Varricchio, D.J., Alcober, O.A., and Larsson, H.C.E. (2008). Kemp, Tom (ed.). "Evidence for Avian Intrathoracic Air Sacs in a New Predatory Dinosaur from Argentina". PLOS ONE. 3 (9): e3303. Bibcode:2008PLoSO...3.3303S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0003303. PMC 2553519. PMID 18825273.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Claessens LP, O'Connor PM, Unwin DM (2009). Sereno P (ed.). "Respiratory evolution facilitated the origin of pterosaur flight and aerial gigantism". PLOS ONE. 4 (2): e4497. Bibcode:2009PLoSO...4.4497C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0004497. PMC 2637988. PMID 19223979.

- Geist, N.; Hillenius, W.; Frey, E.; Jones, T.; Elgin, R. (2014). "Breathing in a box: Constraints on lung ventilation in giant pterosaurs". The Anatomical Record. 297 (12): 2233–2253. doi:10.1002/ar.22839. PMID 24357452.

- Habib, M. (2011). "Dinosaur Revolution: Anhanguera." H2VP: Paleobiomechanics. Weblog entry, 20-SEP-2011. Accessed 28-SEP-2011: http://h2vp.blogspot.com/2011/09/dinosaur-revolution-anhanguera.html

- Pêgas, R. V.; Costa, F. R.; Kellner, A. W. A. (2018). "New Information on the osteology and a taxonomic revision of The genus Thalassodromeus (Pterodactyloidea, Tapejaridae, Thalassodrominae)". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 38 (2): e1443273. doi:10.1080/02724634.2018.1443273.

- Kellner, A.W.A.; Campos, D.A. (2007). "Short note on the ingroup relationships of the Tapejaridae (Pterosauria, Pterodactyloidea". Boletim do Museu Nacional. 75: 1–14.

- Zug, George R. "Turtle: Origin and evolution". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 18 September 2015.

- Martill, D.M., Bechly, G. and Loveridge, R.F. (2007). The Crato fossil beds of Brazil: window into an ancient world. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-85867-4, ISBN 978-0-521-85867-0

- Peter L. Forey & Lance Grande (1998). "An African twin to the Brazilian Calamopleurus (Actinopterygii: Amiidae)". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 123 (2): 179–195. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1998.tb01299.x.

- Cladocyclus at Fossilworks.org

- Sepkoski, Jack (2002). "A compendium of fossil marine animal genera". Bulletins of American Paleontology. 364: 560. Archived from the original on 2011-07-23. Retrieved 2009-02-27.

- Woodward, A.S. (1895). "Catalogue of the Fossil Fishes in the British Museum (Natural History)". 2. British Museum of Natural History Department of Geology: 77–119. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.61854. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Martill, David M.; Green, Mick; Smith, Roy; Jacobs, Megan; Winch, John (April 2020). "First tapejarid pterosaur from the Wessex Formation (Wealden Group: Lower Cretaceous, Barremian) of the United Kingdom". Cretaceous Research. 113: 104487. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2020.104487.

- Charig, A. J.; Milner, A. C. (1986). "Baryonyx, a remarkable new theropod dinosaur". Nature. 324 (6095): 359–361. Bibcode:1986Natur.324..359C. doi:10.1038/324359a0. PMID 3785404.

- Hutt, S.; Simmonds, K.; Hullman, G. (1990). "Predatory dinosaurs from the Isle of Wight". Proceedings of the Isle of Wight Natural History and Archaeological Society. 9: 137–146.

- Carpenter, K.; Ishida, Y. (2010). "Early and "Middle" Cretaceous Iguanodonts in Time and Space". Journal of Iberian Geology. 36 (2): 145–164. doi:10.5209/rev_JIGE.2010.v36.n2.3.

- Hulke, John W. (1873). "Contribution to the anatomy of Hypsilophodon foxii. An account of some recently acquired remains". Geological Society of London, Quarterly Journal. 29 (1–2): 522–532. doi:10.1144/GSL.JGS.1873.029.01-02.46.

- Sweetman, Steven C. (September 2009). "A New Species of the Plagiaulacoid Multituberculate Mammal Eobaatarfrom the Early Cretaceous of Southern Britain". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 54 (3): 373–384. doi:10.4202/app.2008.0003. ISSN 0567-7920.

- "Wessex Formation". The BGS Lexicon of Named Rock Units. British Geological Survey.

- Kellner, Alexander W.A.; Taissa Rodrigues; Fabiana R. Costa (2011). "Short note on a pteranodontoid pterosaur (Pterodactyloidea) from western Queensland, Australia" (PDF). Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências. 83 (1): 301–308. doi:10.1590/S0001-37652011000100018. PMID 21437387.

- Molnar, Ralph E.; Thulborn, R.A. (2008). "An incomplete pterosaur skull from the Cretaceous of north-central Queensland, Australia". Arquivos do Museu Nacional, Rio de Janeiro. 65 (4): 461–470.

- McDonald, A.T.; Kirkland, J.I.; DeBlieux, D.D.; Madsen, S.K.; Cavin, J.; Milner, A.R.C.; Panzarin, L. (2010). "New Basal Iguanodonts from the Cedar Mountain Formation of Utah and the Evolution of Thumb-Spiked Dinosaurs". PLOS ONE. 5 (11): e14075. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...514075M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0014075. PMC 2989904. PMID 21124919.

- Lucy G. Leahey; Ralph E. Molnar; Kenneth Carpenter; Lawrence M. Witmer; Steven W. Salisbury (2015). "Cranial osteology of the ankylosaurian dinosaur formerly known as Minmi sp. (Ornithischia: Thyreophora) from the Lower Cretaceous Allaru Mudstone of Richmond, Queensland, Australia". PeerJ. 3: e1475. doi:10.7717/peerj.1475. PMC 4675105. PMID 26664806.

- Gardiner, J. Stanley (September 1931). "The Harvard Museum Expedition to Australia". Nature. 128 (3228): 457–458. Bibcode:1931Natur.128..457G. doi:10.1038/128457c0.

- White, M. A.; Falkingham, P. L.; Cook, A. G.; Hocknull, S. A.; Elliott, D. A. (2013). "Morphological comparisons of metacarpal I for Australovenator wintonensis and Rapator ornitholestoides: Implications for their taxonomic relationships". Alcheringa: An Australasian Journal of Palaeontology. 37 (4): 435–441. doi:10.1080/03115518.2013.770221.

- Pentland, Adele H.; Poropat, Stephen F.; Tischler, Travis R.; Sloan, Trish; Elliott, Robert A.; Elliott, Harry A.; Elliott, Judy A.; Elliott, David A. (December 2019). "Ferrodraco lentoni gen. et sp. nov., a new ornithocheirid pterosaur from the Winton Formation (Cenomanian–lower Turonian) of Queensland, Australia". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 13454. Bibcode:2019NatSR...913454P. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-49789-4. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 6776501. PMID 31582757.

- Rigal, S.; Martill, D. M.; Sweetman, S. C. (2017). "A new pterosaur specimen from the Upper Tunbridge Wells Sand Formation (Cretaceous, Valanginian) of southern England and a review of Lonchodectes sagittirostris (Owen 1874)". Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 455: 221–232. doi:10.1144/SP455.5.

Further reading

- Wellnhofer, Peter (1991). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Pterosaurs: An illustrated natural history of the flying reptiles of the Mesozoic Era. Crescent Books. ISBN 0517037017.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Witton, Mark (2013). Pterosaurs: Natural History, Evolution, Anatomy. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691150611.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)