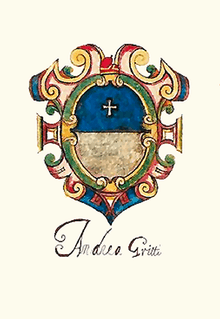

Andrea Gritti

Andrea Gritti (17 April 1455 – 28 December 1538) was the Doge of Venetian Republic from 1523 to 1538, following a distinguished diplomatic and military career.

| Andrea Gritti | |

|---|---|

Portrait by Titian (1540) | |

| 77th Doge of Venice | |

| Dogado | 20 May 1523 – 28 December 1538 |

| Predecessor | Antonio Grimani |

| Successor | Pietro Lando |

| Born | 17 April 1455 Bardolino, Republic of Venice |

| Died | 28 December 1538 (aged 83) Venice, Republic of Venice |

| Burial | |

| Spouse | Benedetta Vendramin |

| Children | Francesco, Alvise |

| Dynasty | Gritti family |

| Father | Francesco Gritti |

| Mother | Vienna Zane |

| Occupation | Merchant, military officer, politician |

Early life

_-_Choir_-_Monument_to_Andrea_Gritti.jpg)

Andrea Gritti was born on 17 April 1455 in Bardolino, near Verona.[1] His father, Francesco, son of Triadano Gritti, died soon after, and his mother, Vienna, daughter of Paolo Zane, remarried in 1460 to Giacomo Malipiero, with whom she had two more sons, Paolo and Michele. Andrea had a very close relationship with his half-brothers.[1] Andrea was brought up by his paternal grandfather, receiving his first education at his grandfather's house in Venice, before going on to study at the University of Padua. At the same time he accompanied his grandfather on diplomatic missions to England, France, and Spain.[1]

Merchant in Constantinople

In 1476 he married Benedetta, daughter of Luca Vendramin, but she died at childbirth of their son, Francesco, on the same year.[1] Widowed, Gritti moved to the Ottoman capital, Constantinople, where he engaged in trade, particularly of cereals, often in partnership with the Genoese merchant Pantaleo Coresi.[1] He enjoyed the guidance of his great-uncle, Battista Gritti, who gave him insight on important officials and traders.[1] Gritti's enterprise was successful and allowed him to live a prosperous life during his almost twenty-year stay in the city. At his home in the quarter of Galata, he lived with a Greek woman, with whom he had four illegitimate sons: Alvise, Giorgio, Lorenzo, Pietro. He also became a person of prominence in the Italian community of Galata, serving as head of the Venetian community. He also enjoyed a good relationship with the Ottoman grand vizier, Hersekzade Ahmed Pasha, securing from him various accommodations and exemptions in exchange for frequent monetary donations, as well as the esteem of Ahmed Pasha's father-in-law, Sultan Bayezid II.[1]

In 1492, the Venetian Bailo in Constantinople, Girolamo Marcello, was expelled on the charge of espionage. The post remained vacant, and Gritti assumed the task of representing Venice at the Ottoman court.[1] Lacking an official appointment, however, his position was precarious, especially as, with another Ottoman–Venetian conflict looming in 1499, he used his commercial correspondence, sent via Corfu and the Ragusan merchant Nicolò Gondola, to transmit encoded information to the Venetian Senate regarding the movements of the Ottoman navy (referred to as "carpets" in one letter) and troop concentrations.[1][2] This activity did not remain hidden from the Turks for long, however: after capturing couriers bearing Gritti's letters, in August 1499 he was imprisoned in the Yedikule Fortress, escaping execution only through his friendship with the grand vizier. According to contemporary reports, his imprisonment caused great consternation among his many friends—including Turks—at the Ottoman capital, as well as the many women enamoured in him.[1]

Gritti nevertheless spent 32 months in the fortress, along with other Venetian merchants, coming close to death due to the privations of this long imprisonment. He was released after a ransom of 2,400 ducats was paid, and returned to Venice.[1] Gritti played a role in the negotiations and conclusion of the peace treaty with the Ottoman Empire in December 1502, and then took active part in the reception of the Ottoman ambassador Ali Bey and the finalization of the treaty on 20 May 1503. Gritti's experience with the diplomatic customs of the Ottomans led to his being charged with overseeing the final formulation of the treaty's clauses, so as to remove any ambiguities and causes for misinterpretation.[1] Finally, on 22 May, he left Venice with Ali Bey for Constantinople, bearing the draft treaty and a letter by the Doge to the Sultan. After the ratification of the treaty by the Sultan, he returned to Venice, making his report in the Senate on 2 December 1503.[1]

Political and military career

The war and his long imprisonment put an end to Gritti's commercial career, costing him the enormous sum of 24,000 ducats. With little hope of recompense for his losses, he was forced in 1517 to ask the Senate's permission to accept a gift from the King of France as partial restitution of his losses.[1] Rather than retiring, however, he now embarked on an active political career.[1]

In the early sixteenth century, Venice lost nearly all its territory on the Italian mainland during the War of the League of Cambrai, and Gritti played an important part in the events connected with this loss and the eventual return to the status quo ante. In 1509, after the Venetian defeat at the Battle of Agnadello, Gritti was appointed as proveditor to the Venetian army in Treviso; ordered by the Council of Ten to support revolts against the invaders, he successfully engineered the return of Padua to Venetian hands, and its subsequent defence against the Emperor. In 1510, following the death of Niccolò di Pitigliano, Gritti took command of Venice's army, but was forced to withdraw to Venice by French advances. He continued as proveditor through end of the conflict. In 1512, he led the negotiations with Francis I of France that resulted in Venice leaving the League and allying with France.

Dogeship

Elected Doge in 1523, Gritti concluded a treaty with Charles V, ending Venice's active involvement in the Italian Wars. He attempted to maintain the neutrality of the Republic in the face of the continued struggle between Charles and Francis, urging both to turn their attention to the advances of the Ottoman Empire in Hungary. However, he could not prevent Suleiman I from attacking Corfu in 1537, drawing Venice into a new war with the Ottomans. His dogaressa was Benedetta Vendramin.[3]

Gritti died on 28 December 1538.[1]

Popular culture

- A portrait of Andrea Gritti sometimes appears in the loading screen of the PC strategy game, Europa Universalis IV. The Venetian Republic is a popular playable nation in the game.

- a portrait of Andrea Gritti is also featured in the live action video game, MagiQuest. When you cast at the portrait, his eyes glow red.*

References

- Benzoni, Gino (2002). "GRITTI, Andrea". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, Volume 59: Graziano–Grossi Gondi (in Italian). Rome: Istituto dell'Enciclopedia Italiana.

- Labalme P.H. & Sanguineti White L. (eds.) (2008) Venice, cità excelentissima: selections from the Renaissance diaries of Marino Sanudo, Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, pp. 232-235.

- Staley, Edgcumbe: The dogaressas of Venice : The wives of the doges. London : T. W. Laurie

Sources

- Finlay, Robert, "Fabius Maximus in Venice: Doge Andrea Gritti, the War of Cambrai, and the Rise of Habsburg Hegemony, 1509-1530," Renaissance Quarterly 53:988–1031, Winter 2000.

- Norwich, John Julius (1989). A History of Venice. New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 0-679-72197-5.

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Antonio Grimani |

Doge of Venice 1523–1538 |

Succeeded by Pietro Lando |