Analytical psychology

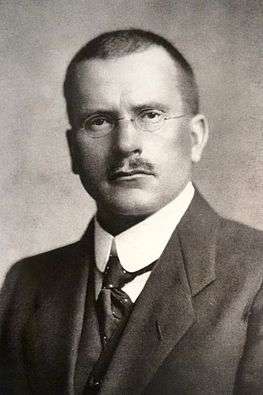

Analytical psychology (German: Analytische Psychologie, sometimes translated as analytic psychology and referred to as Jungian analysis) is the name Carl Jung, a Swiss psychiatrist, gave to his new "empirical science" of the psyche to distinguish it from Freud's psychoanalytic theories as their seven year collaboration on psychoanalysis was drawing to an end between 1912 and 1913.[1][2][3] The evolution of his science is contained in his monumental opus, the Collected Works, written over sixty years of his lifetime.[4]

Among widely used concepts owed specifically to Analytical psychology are: anima and animus, archetypes, the collective unconscious, complexes, extraversion and introversion, individuation, the Self, the shadow and synchronicity.[5][6] The Myers–Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) is based on another of Jung's theories on psychological types.[5][7][8] A less well known idea was Jung's notion of the Psychoid to denote a hypothesised immanent plane beyond consciousness, distinct from the collective unconscious, and a potential locus of synchronicity.[9]

The approximately "three schools" of post-Jungian analytical psychology that are current, the classical, archetypal and developmental, can be said to correspond to the developing yet overlapping aspects of Jung's lifelong explorations, even if he expressly did not want to start a school of "Jungians".[5](pp. 50–53)[10] Hence as Jung proceeded from a clinical practice which was mainly traditionally science-based and steeped in rationalist philosophy, his enquiring mind simultaneously took him into more esoteric spheres such as alchemy, astrology, Gnosticism, metaphysics, the occult and the paranormal, without ever abandoning his allegiance to science as his long lasting collaboration with Wolfgang Pauli attests.[11] His wide ranging progression suggests to some commentators that, over time, his analytical psychotherapy, informed by his intuition and teleological investigations, became more of an "art".[5]

Origins

Jung began his career as a psychiatrist in Zürich, Switzerland. Already employed at the famous Burghölzli hospital in 1901, in his academic dissertation for the medical faculty of the University of Zurich he took the risk of using his experiments on somnambulism and the visions of his mediumistic cousin, Helly Preiswerk. The work was entitled, "On the Psychology and Pathology of So-Called Occult Phenomena".[12] It was accepted but caused great upset among his mother's family.[13] Under the direction of psychiatrist Eugen Bleuler, he also conducted research with his colleagues using a galvanometer to evaluate the emotional sensitivities of patients to lists of words during word association.[13][14][15][16] Jung has left a description of his use of the device in treatment.[17][18][19] His research earned him a worldwide reputation and numerous honours, including Honorary Doctorates from Clark and Fordham Universities in 1909 and 1910 respectively. Other honours followed later.[20][21]

Although they began corresponding a year earlier, in 1907 Jung travelled to meet Sigmund Freud in Vienna, Austria. At that stage Jung, aged thirty two, had a much greater international renown than the seventeen years older neurologist.[13] For a further six years, the two scholars worked and travelled to the United States together. In 1911, they founded the International Psychoanalytical Association, of which Jung was the first president.[13] However, early in the collaboration, Jung had already observed that Freud would not tolerate ideas that were different from his own.[13]

Unlike most modern psychologists, Jung did not believe in restricting himself to the scientific method as a means to understanding the human psyche. He saw dreams, myths, coincidence and folklore as empirical evidence to further understanding and meaning. So although the unconscious cannot be studied by using direct methods, it acts as a useful working hypothesis, according to Jung.[22] As he said, "The beauty about the unconscious is that it is really unconscious."[23] Hence, the unconscious is 'untouchable' by experimental researches, or indeed any possible kind of scientific or philosophical reach, precisely because it is unconscious.

Divergence from psychoanalytic theory

In 1912, Jung published Psychology of the Unconscious (Wandlungen und Symbole der Libido) (re-published as Symbols of Transformation in 1952) (C.W. Vol. 5).[13] The innovative ideas it contained contributed to a new formulation of psychology and spelled the end of the Jung-Freud friendship in 1913. From then, the two scholars worked independently on personality development: Jung had already termed his approach analytical psychology (1912), while the approach Freud had founded is referred to as the Psychoanalytic School, (psychoanalytische Schule).[1]

Jung's postulated unconscious was quite different from the model proposed by Freud, despite the great influence that the founder of psychoanalysis had had on him. In particular, tensions manifested between him and Freud because of various disagreements, including those concerning the nature of the libido.[24] Jung de-emphasized the importance of sexual development as an instinctual drive and focused on the collective unconscious: the part of the unconscious that contains memories and ideas which Jung believed were inherited from generations of ancestors. While he accepted that libido was an important source for personal growth, unlike Freud, Jung did not consider that libido alone was responsible for the formation of the core personality.[25] Due to the particular hardships Jung had endured growing up, he believed his personal development and that of everyone was influenced by factors unrelated to sexuality.[24]

The overarching aim in life, according to Jungian psychology, is the fullest possible actualisation of the "Self" through individuation.[26][6] Jung defines the "self" as "not only the centre but also the whole circumference which embraces both conscious and unconscious; it is the centre of this totality, just as the ego is the centre of the conscious mind".[27] Central to this process of individuation is the individual's continual encounter with the elements of the psyche by bringing them into consciousness.[6] People experience the unconscious through symbols encountered in all aspects of life: in dreams, art, religion, and the symbolic dramas enacted in relationships and life pursuits.[6] Essential to the process is the merging of the individual's consciousness with the collective unconscious through a huge range of symbols. By bringing conscious awareness to bear on what is unconscious, such elements can be integrated with consciousness when they "surface".[6] To proceed with the individuation process, individuals need to be open to the parts of themselves beyond their own ego, which is the "organ" of consciousness.[6] In a famous dictum, Jung said, "the Self, like the unconscious is an a priori existent out of which the ego evolves. It is ... an unconscious prefiguration of the ego. It is not I who create myself, rather I happen to myself'.[28]

It follows that the aim of (Jungian) psychotherapy is to assist the individual to establish a healthy relationship with the unconscious so that it is neither excessively out of balance in relation to it, as in neurosis, a state that can result in depression, anxiety, and personality disorders or so flooded by it that it risks psychosis resulting in mental breakdown. One method Jung applied to his patients between 1913 and 1916 was active imagination, a way of encouraging them to give themselves over to a form of meditation to release apparently random images from the mind in order to bridge unconscious contents into awareness.[29]

"Neurosis" in Jung's view results from the build up of psychological defences the individual unconsciously musters in an effort to cope with perceived attacks from the outside world, a process he called a "complex", although complexes are not merely defensive in character.[6] The psyche is a self-regulating adaptive system.[6] People are energetic systems, and if the energy is blocked, the psyche becomes sick. If adaptation is thwarted, the psychic energy stops flowing becomes rigid. This process manifests in neurosis and psychosis. Jung proposed that this occurs through maladaptation of one's internal realities to external ones. The principles of adaptation, projection, and compensation are central processes in Jung's view of psyche's attempts to adapt.

Principal concepts

Anima and animus

Jung identified the anima as being the unconscious feminine component of men and the animus as the unconscious masculine component in women.[30] These are shaped by the contents of the collective unconscious, by others, and by the larger society.[30] However, many modern-day Jungian practitioners do not ascribe to a literal definition, citing that the Jungian concept points to every person having both an anima and an animus.[31] Jung considered, for instance, an "animus of the anima" in men, in his work Aion and in an interview in which he says:

"Yes, if a man realizes the animus of his anima, then the animus is a substitute for the old wise man. You see, his ego is in relation to the unconscious, and the unconscious is personified by a female figure, the anima. But in the unconscious is also a masculine figure, the wise old man. And that figure is in connection with the anima as her animus, because she is a woman. So, one could say the wise old man was in exactly the same position as the animus to a woman."[32]

Jung stated that the anima and animus act as guides to the unconscious unified Self, and that forming an awareness and a connection with the anima or animus is one of the most difficult and rewarding steps in psychological growth. Jung reported that he identified his anima as she spoke to him, as an inner voice, unexpectedly one day.

In cases where the anima or animus complexes are ignored, they vie for attention by projecting itself on others.[33] This explains, according to Jung, why we are sometimes immediately attracted to certain strangers: we see our anima or animus in them. Love at first sight is an example of anima and animus projection. Moreover, people who strongly identify with their gender role (e.g. a man who acts aggressively and never cries) have not actively recognized or engaged their anima or animus.

Jung attributes human rational thought to be the male nature, while the irrational aspect is considered to be natural female (rational being defined as involving judgment, irrational being defined as involving perceptions). Consequently, irrational moods are the progenies of the male anima shadow and irrational opinions of the female animus shadow.

Archetypes

The use of psychological archetypes was advanced by Jung in 1919. In Jung's psychological framework, archetypes are innate, universal prototypes for ideas and may be used to interpret observations. A group of memories and interpretations associated with an archetype is a complex, e.g. a mother complex associated with the mother archetype. Jung treated the archetypes as psychological organs, analogous to physical ones in that both are morphological givens that arose through evolution.

Archetypes are collective as well as individual, and can grow on their own and present themselves in a variety of creative ways. Jung, in his book Memories, Dreams, Reflections, states that he began to see and talk to a manifestation of anima and that she taught him how to interpret dreams. As soon as he could interpret on his own, Jung said that she ceased talking to him because she was no longer needed.[34]

Collective unconscious

Jung's concept of the collective unconscious has often been misunderstood, and it is related to the Jungian archetypes. The term "collective unconscious" first appeared in Jung's 1916 essay, "The Structure of the Unconscious".[35] This essay distinguishes between the "personal", Freudian unconscious, filled with fantasies (e. g. sexual) and repressed images, and the "collective" unconscious encompassing the soul of humanity at large.[36]

In "The Significance of Constitution and Heredity in Psychology" (November 1929), Jung wrote:

And the essential thing, psychologically, is that in dreams, fantasies, and other exceptional states of mind the most far-fetched mythological motifs and symbols can appear autochthonously at any time, often, apparently, as the result of particular influences, traditions, and excitations working on the individual, but more often without any sign of them. These "primordial images" or "archetypes," as I have called them, belong to the basic stock of the unconscious psyche and cannot be explained as personal acquisitions. Together they make up that psychic stratum which has been called the collective unconscious. The existence of the collective unconscious means that individual consciousness is anything but a tabula rasa and is not immune to predetermining influences. On the contrary, it is in the highest degree influenced by inherited presuppositions, quite apart from the unavoidable influences exerted upon it by the environment. The collective unconscious comprises in itself the psychic life of our ancestors right back to the earliest beginnings. It is the matrix of all conscious psychic occurrences, and hence it exerts an influence that compromises the freedom of consciousness in the highest degree, since it is continually striving to lead all conscious processes back into the old paths.[37]

Shadow

The shadow is an unconscious complex defined as the repressed, suppressed or disowned qualities of the conscious self. According to Jung, the human being deals with the reality of the shadow in four ways: denial, projection, integration and/or transmutation. According to analytical psychology, a person's shadow may have both constructive and destructive aspects. In its more destructive aspects, the shadow can represent those things people do not accept about themselves. For instance, the shadow of someone who identifies as being kind may be harsh or unkind. Conversely, the shadow of a person who perceives himself to be brutal may be gentle. In its more constructive aspects, a person's shadow may represent hidden positive qualities. This has been referred to as the "gold in the shadow". Jung emphasized the importance of being aware of shadow material and incorporating it into conscious awareness in order to avoid projecting shadow qualities on others.

The shadow in dreams is often represented by dark figures of the same gender as the dreamer.[38]

The shadow may also concern great figures in the history of human thought or even spiritual masters, who became great because of their shadows or because of their ability to live their shadows (namely, their unconscious faults) in full without repressing them.

Psychological types

Analytical psychology distinguishes several psychological types or temperaments.

According to Jung, the psyche is an apparatus for adaptation and orientation, and consists of a number of different psychic functions. Among these he distinguishes four basic functions:[39]

- Sensation – Perception by means of the sense organs

- Intuition – Perceiving in unconscious way or perception of unconscious contents

- Thinking – Function of intellectual cognition; the forming of logical conclusions

- Feeling – Function of subjective estimation

Thinking and feeling functions are rational, while the sensation and intuition functions are irrational.

Note: There is ambiguity in the term 'rational' that Carl Jung ascribed to the thinking/feeling functions. Both thinking and feeling irrespective of orientation (i.e., introverted/extroverted) employ/utilize/are directed by in loose terminology an underlying 'logical' IF-THEN construct/process (as in IF X THEN Y) in order to form judgments. This underlying construct/process is not directly observable in normal states of consciousness especially when engaged in thoughts/feelings. It can be cognized merely as a concept/abstraction during thoughtful reflection. Sensation and intuition are 'irrational' functions simply because they do not employ the above-mentioned underlying logical construct/process.

Complexes

Early in Jung's career he coined the term and described the concept of the "complex". Jung claims to have discovered the concept during his free association and galvanic skin response experiments. Freud obviously took up this concept in his Oedipus complex amongst others. Jung seemed to see complexes as quite autonomous parts of psychological life. It is almost as if Jung were describing separate personalities within what is considered a single individual, but to equate Jung's use of complexes with something along the lines of multiple personality disorder would be a step out of bounds.

Jung saw an archetype as always being the central organizing structure of a complex. For instance, in a "negative mother complex," the archetype of the "negative mother" would be seen to be central to the identity of that complex. This is to say, our psychological lives are patterned on common human experiences. Jung saw the Ego (which Freud wrote about in German literally as the "I", one's conscious experience of oneself) as a complex. If the "I" is a complex, what might be the archetype that structures it? Jung, and many Jungians, might say "the hero," one who separates from the community to ultimately carry the community further.

Innovations of Jungian analysis

Jungian Analysis, as is psychoanalysis, is a method to access, experience and integrate unconscious material into awareness. It is a search for the meaning of behaviours, feelings and events. Many are the channels to extend knowledge of the self: the analysis of dreams is one important avenue. Others may include expressing feelings about and through art, poetry or other expressions of creativity, the examination of conflicts and repeating patterns in a person's life. A comprehensive description of the process of dream interpretation is complex, in that it is highly specific to the person who undertakes it. Most succinctly it relies on the associations which the particular dream symbols suggest to the dreamer, which at times may be deemed "archetypal" in so far as they are supposed common to many people throughout history. Examples could be a hero, an old man or woman, situations of pursuit, flying or falling.

Whereas (Freudian) psychoanalysis relies entirely on the development of the transference in the analysand to the analyst, Jung initially used the transference and later concentrated more on a dialectical and didactic approach to the symbolic and archetypal material presented by the patient. Moreover his attitude towards patients departed from what he had observed in Freud's method. Anthony Stevens has explained it thus:

- Though [Jung's] initial formulations arose mainly out of his own creative illness, they were also a conscious reaction against the stereotype of the classical Freudian analyst, sitting silent and aloof behind the couch, occasionally emitting ex cathedra pronouncements and interpretations, while remaining totally uninvolved in the patient's guilt, anguish, and need for reassurance and support. Instead, Jung offered the radical proposal that analysis is a dialectical procedure, a two-way exchange between two people, who are equally involved. Although it was a revolutionary idea when he first suggested it, it is a model which has influenced psychotherapists of most schools, though many seem not to realise that it originated with Jung.[40]

In place of Freud's "surgical detachment", Jung demonstrated a more relaxed and warmer welcome in the consulting room.[40] He remained aware nonetheless that exposure to a patient's unconscious contents always posed a certain risk of contagion (he calls it "psychic infection") to the analyst, as experienced in the countertransference.[41] The process of contemporary Jungian analysis depends on the type of "school of analytical psychology" to which the therapist adheres, (see below). The "Zurich School" would reflect the approach Jung himself taught, while those influenced by Michael Fordham and associates in London, would be significantly closer to a Kleinian approach and therefore, concerned with analysis of the transference and countertransference as indicators of repressed material along with the attendant symbols and patterns.[42]

Post-Jungian approaches

Andrew Samuels (1985) has distinguished three distinct traditions or approaches of "post-Jungian" psychology – classical, developmental and archetypal. Today there are more developments.

Classical

The classical approach tries to remain faithful to Jung's proposed model, his teachings and the substance of his 20 volume Collected Works, together with still emerging publications such as the Liber Novus.[43] Prominent advocates of this approach, according to Samuels (1985), include Emma Jung, Jung's wife, an analyst in her own right, Marie-Louise von Franz, Joseph L. Henderson, Aniela Jaffé, Erich Neumann, Gerhard Adler and Jolande Jacobi. Jung credited Neumann, author of "Origins of Conscious" and "Origins of the Child", as his principal student to advance his (Jung's) theory into a mythology-based approach.[44] He is associated with developing the symbolism and archetypal significance of several myths: the Child, Creation, the Hero, the Great Mother and Transcendence.[10]

Archetypal

One archetypal approach, sometimes called "the imaginal school" by James Hillman, was written about by him in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Its adherents, according to Samuels (1985), include Murray Stein, Rafael Lopez-Pedraza and Wolfgang Giegerich. Thomas Moore also was influenced by some of Hillman's work. Developed independently, other psychoanalysts have created strong approaches to archetypal psychology. Mythopoeticists and psychoanalysts such as Clarissa Pinkola Estés who believes that ethnic and aboriginal people are the originators of archetypal psychology and have long carried the maps for the journey of the soul in their songs, tales, dream-telling, art and rituals; Marion Woodman who proposes a feminist viewpoint regarding archetypal psychology. Some of the mythopoetic/archetypal psychology creators either imagine the Self not to be the main archetype of the collective unconscious as Jung thought, but rather assign each archetype equal value. Others, who are modern progenitors of archetypal psychology (such as Estés), think of the Self as the thing that contains and yet is suffused by all other archetypes, each giving life to the other.

Robert L. Moore has explored the archetypal level of the human psyche in a series of five books co-authored with Douglas Gillette, which have played an important role in the men's movement in the United States. Moore studies computerese so he uses a computer's hard wiring (its fixed physical components) as a metaphor for the archetypal level of the human psyche. Personal experiences influence the access to the archetypal level of the human psyche, but personalized ego consciousness can be likened to computer software.

Developmental

A major expansion of Jungian theory is credited to Michael Fordham and his wife, Frieda Fordham. It can be considered a bridge between traditional Jungian analysis and Melanie Klein's object relations theory. Judith Hubback and Goodheart are also often mentioned. Andrew Samuels (1985) considers J.W.T. Redfearn, Richard Carvalho and himself as representatives of the developmental approach. Samuels notes how this approach differs from the classical by giving less emphasis to the Self and more emphasis to the development of personality; he also notes how, in terms of practice in therapy, it gives more attention to transference and counter-transference than either the classical or the archetypal approaches.

Process-oriented psychology

Process-oriented psychology (also called Process work) is associated with the Zurich-trained Jungian analyst Arnold Mindell. Process work developed in the late 1970s and early 1980s and was originally identified as a "daughter of Jungian psychology".[45] Process work stresses awareness of the "unconscious" as an ongoing flow of experience. This approach expands Jung's work beyond verbal individual therapy to include body experience, altered and comatose states as well as multicultural group work.

See also

References

- Jung, C. G. (1912). Neue Bahnen in der Psychologie (in German). Zürich. (New Pathways in Psychology)

- Samuels, A., Shorter, B. and Plaut, F. (1986). A Critical Dictionary of Jungian Analysis. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul. ISBN 978-0-415-05910-7.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- "Analytic Psychology". Encyclopaedia Britannica.

- "Collected Works of C.G. Jung, Complete Digital Edition". Princeton University Press. Retrieved 2014-01-23.

- Fordham, Michael (1978). Jungian Psychotherapy: A Study in Analytical Psychology. London: Wiley & Sons. pp. 1–8. ISBN 0 471 99618 1.

- Anthony Stevens (1990). Archetype: A Natural History of the Self. Hove: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415052207.

- Jung, Carl Gustav (August 1, 1971). "Psychological Types". Collected Works of C. G. Jung, Volume 6. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-09770-1.

- McCrae, R.; Costa, P. (1989). "Reinterpreting the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator from the perspective of the five-factor model of personality". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Ann Addison (2009). "Jung, vitalism and 'the psychoid': an historical reconstruction". Journal of Analytical Psychology. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5922.2008.01762.x.

- Samuels, Andrew (1985). Jung and the Post-Jungians. London and Boston: Routledge & Kegan Paul plc. pp. 11-21. ISBN 0-7100-9958-4.

- Remo, F. Roth (2012). Return of the World Soul, Wolfgang Pauli, C. G. Jung and the Challenge of Psychophysical Reality [unus mundus], Part 2: A Psychophysical Theory. Pari Publishing. ISBN 978-88-95604-16-9.

- Jung. CW 1. pp. 3–88

- Bair, Deirdre (2004). Jung, A Biography. London: Little Brown. ISBN 0 316 85434 4.

- Binswanger, L. (1919). "XII". In Jung, Carl (ed.). Studies in Word-Association. New York, NY: Moffat, Yard & company. pp. 446 et seq. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- Note: Jung was so impressed with EDA monitoring, he allegedly cried, "Aha, a looking glass into the unconscious!"

- Brown, Barbara (November 9, 1977). "Skin Talks -- And It May Not Be Saying What You Want To". Pocatello, Idaho: Field Enterprises, Inc. Idaho State Journal. p. 32. Retrieved 8 April 2015.

- Mitchell, Gregory. "Carl Jung & Jungian Analytical Psychology". Mind Development Courses. Retrieved 9 April 2015.

- Daniels, Victor. "Notes on Carl Gustav Jung". Sonoma State University. Sonoma State University. Retrieved 4 April 2015.

By 1906 [Jung] was using GSR and breath measurement to note changes in respiration and skin resistance to emotionally charged worlds. He found that indicators cluster around stimulus words which indicate the nature of the subject's complexes.

- The Biofeedback Monitor Archived 2008-09-15 at the Wayback Machine

- Wehr, Gerhard (1987). Jung - A Biography. Translated by Weeks, David. M. Boston: Shambala. pp. 501-505. ISBN 0-87773-455-0.

- Roazen, Paul. (1976) Erik Erikson, pp. 8-9. The Harvard Fellowship was intended for Freud who was too ill to travel, so to save emoluments going elsewhere, it was offered to Jung, who accepted.

- Martin-Vallas François (2013). "Quelques remarques à propos de la théorie des archétypes et de son épistémologie". Revue de Psychologie Analytique (in French) (1): 99–134..

- Jung on film.

- Jung, Carl (1963). Memories, Dreams, Reflections. Pantheon Books. p. 206.

- Carlson, Heth (2010). Psychology: The Science of Behavior. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson. p. 434. ISBN 978-0-205-64524-4.

- Jung. CW. 7. para. 266.

- Jung. CW. 12. para. 44

- Jung. CW 11, para. 391.

- Hoerni, Ulrich; Fischer, Thomas; Kaufmann, Bettina, eds. (2019). The Art of C.G. Jung. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 260. ISBN 978-0-393-25487-7.

- Jackson, Kathy Merlock (2005). Rituals and Patterns in Children's Lives. Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press. p. 225. ISBN 0-299-20830-3.

- Ivancevic, Vladimir G.; Ivancevic, Tijana T. (2007). Computational Mind: A Complex Dynamics Perspective. Berlin: Springer. p. 108. ISBN 9783540714651.

- Jung, C. G. (1988-09-21). Nietzsche's Zarathustra. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691099538.

- Maciocia, Giovanni (2009). The Psyche in Chinese Medicine: Treatment of Emotional and Mental Disharmonies with Acupuncture and Chinese Herbs. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier. p. 301. ISBN 978-0-7020-2988-2.

- "Wikischool". Wikischool. Retrieved 2020-05-15.

- Young-Eisendrath & Dawson, Cambridge Companion to Jung (2008), "Chronology" (pp. xxiii–xxxvii). According to the 1953 Collected Works editors, the 1916 essay was translated by M. Marsen from German into French and published as "La Structure de l'inconscient" in Archives de Psychologie XVI (1916); they state that the original German manuscript no longer exists.

- Jung, Collected Works vol. 7 (1953), "The Structure of the Unconscious" (1916), ¶437–507 (pp. 263–292).

- Jung, Collected Works vol. 8 (1960), "The Significance of Constitution and Heredity in Psychology" (1929), ¶229–230 (p. 112).

- Jung, C.G. (1958–1967). Psyche and Symbol. (R. F. C. Hull, Trans.). Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press (published 1991).

- Jung, C.G., "Psychological Types" (The Collected Works of C.G. Jung, Vol.6).

- Stevens, Anthony (1998). An Intelligent Person's Guide to Psychotherapy. London: Gerald Duckworth & Co. p. 67. ISBN 0 7156 2820 8.

- Jung. CW 16. paras. 364-65.

- Fordham, Michael (1978). Jungian Psychotherapy, A Study in Analytical Psychology. London: John Wiley & Sons Ltd. ISBN 0 471 99618 1.

- The Red Book: Liber Novus. tr. M. Kyburz, J. Peck and S. Shamdasani. New York: W. W. Norton, 2009. ISBN 978-0-393-06567-1.

- Jung, C. G., Neumann, Erich. (2015). Liebscher, Martin. Introduction (ed.). Analytical Psychology in Exile: The Correspondence of C. G. Jung and Erich Neumann (Philemon Foundation Series). Translated by Heather McCartney. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691166179.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Julie Diamond (2004). A Path Made by Walking. Lao Tse Press. p. 6.

In the mid-1980s, Arnold Mindell presented a lecture called ‘Jungian Psychology has a Daughter’ to the Jungian community in Zurich.

Bibliography

- Aziz, Robert (1990). C.G. Jung's Psychology of Religion and Synchronicity (10 ed.). The State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-7914-0166-9.

- Aziz, Robert (1999). "Synchronicity and the Transformation of the Ethical in Jungian Psychology". In Becker, Carl (ed.). Asian and Jungian Views of Ethics. Greenwood. ISBN 0-313-30452-1.

- Aziz, Robert (2007). The Syndetic Paradigm: The Untrodden Path Beyond Freud and Jung. The State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-6982-8.

- Aziz, Robert (2008). "Foreword". In Storm, Lance (ed.). Synchronicity: Multiple Perspectives on Meaningful Coincidence. Pari Publishing. ISBN 978-88-95604-02-2.

- Christopher, Elphis; Solomon McFarland, Hester, eds. (2000). Jungian Thought in the Modern World. Free Association Books. ISBN 978-1-853434662.

- Clift, Wallace (1982). Jung and Christianity: The Challenge of Reconciliation. The Crossroad Publishing Company. ISBN 0-8245-0409-7.

- Clift, Jean Dalby; Clift, Wallace (1996). The Archetype of Pilgrimage: Outer Action With Inner Meaning. The Paulist Press. ISBN 0-8091-3599-X.

- Dohe, Carrie B. Jung's Wandering Archetype: Race and Religion in Analytical Psychology. London: Routledge, 2016. ISBN 978-1138888401

- Fappani, Frederic (2008). Education and Archetypal Psychology. Cursus.

- Fordham, Frieda (1966). An Introduction to Jung's Psychology. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books Ltd. ISBN 978-0140202731.

- Mayes, Clifford (2005). Jung and education; elements of an archetypal pedagogy. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-57886-254-2.

- Mayes, Clifford (2007). Inside Education: Depth Psychology in Teaching and Learning. Atwood Publishing. ISBN 978-1-891859-68-7.

- Samuels, Andrew (1985). Jung and the Post-Jungians. Routledge. ISBN 0-203-35929-1.

- Remo, F. Roth: Return of the World Soul, Wolfgang Pauli, C.G. Jung and the Challenge of Psychophysical Reality [unus mundus], Part 1: The Battle of the Giants. Pari Publishing, 2011, ISBN 978-88-95604-12-1.

- Remo, F. Roth: Return of the World Soul, Wolfgang Pauli, C.G. Jung and the Challenge of Psychophysical Reality [unus mundus], Part 2: A Psychophysical Theory. Pari Publishing, 2012, ISBN 978-88-95604-16-9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Analytical psychology. |

- Archive for Research in Archetypal Symbolism

- Harvest a scholarly journal of the Jung Club, London

- International Association of Analytical Psychology

- International Association for Jungian Studies

- Website of the Journal of Analytical Psychology, considered the foremost international publication on AP

- Pacifica Graduate Institute, a graduate school offering programs in Jungian and post-Jungian studies

- "An Outline of Analytical Psychology", by Edward F. Edinger

- Jung Arena - Analytical psychology books, journals and resources

- Carl Jung - Life and Work

- ADEPAC Colombia, offering analytical psychology news, biographies and resources

.jpeg)