Air Canada Flight 797

Air Canada Flight 797 was an international passenger flight operating from Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport to Montréal–Dorval International Airport, with an intermediate stop at Toronto Pearson International Airport. On 2 June 1983, the McDonnell Douglas DC-9-32 operating the service developed an in-flight fire behind the lavatory that spread between the outer skin and the inner decor panels, filling the plane with toxic smoke. The spreading fire also burned through crucial electrical cables that disabled most of the instrumentation in the cockpit, forcing the plane to divert to Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky International Airport. Ninety seconds after the plane landed and the doors were opened, the heat of the fire and fresh oxygen from the open exit doors created flashover conditions, and the plane's interior immediately became engulfed in flames, killing 23 passengers who had yet to evacuate the aircraft.[1]

An Air Canada DC-9 similar to the aircraft involved in the accident. | |

| Accident | |

|---|---|

| Date | 2 June 1983 |

| Summary | In-flight fire of unknown origin |

| Site | Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky International Airport Boone County, Kentucky, U.S. 39.0489°N 84.6678°W |

| Aircraft | |

| Aircraft type | McDonnell Douglas DC-9-32 |

| Operator | Air Canada |

| Registration | C-FTLU |

| Flight origin | Dallas/Fort Worth Int'l Airport |

| Stopover | Toronto Pearson International Airport |

| Destination | Montreal-Trudeau Int'l Airport |

| Occupants | 46 |

| Passengers | 41 |

| Crew | 5 |

| Fatalities | 23 |

| Injuries | 16 |

| Survivors | 23 |

The accident became a watershed for global aviation regulations, which were changed in the aftermath of the accident to make aircraft safer. New requirements to install smoke detectors in lavatories, strip lights marking paths to exit doors, and increased firefighting training and equipment for crew became standard across the industry, while regulations regarding evacuation were also updated. Since the accident, it has become mandatory for aircraft manufacturers to prove their aircraft could be evacuated within 90 seconds of the commencement of an evacuation, and passengers seated in overwing exits are now instructed to assist in an emergency situation.

Flight and crew

At 16:25 Eastern Daylight Time[lower-alpha 1] on 2 June 1983, Flight 797 took off from Dallas-Fort Worth International Airport. The flight was a regularly scheduled passenger flight operated by Air Canada using a McDonnell Douglas DC-9-32 (aircraft registration C-FTLU[3]). The flight was scheduled to make a stop at Toronto International Airport, ultimately bound for Montreal's Dorval Airport.[2]:2

The flight's captain, Donald Cameron (age 51), had been employed by Air Canada since 1966. At the time of the accident, Cameron had approximately 13,000 flight hours, of which 4,939 were in the DC-9. First officer Claude Ouimet (age 34) had flown for Air Canada since 1973, and had about 5,650 hours of flight experience, including 2,499 hours in the DC-9.[2]:80

Incident

Fire

While flying over Louisville, Kentucky, an in-flight fire started in or around the rear lavatory of the aircraft. The pilots heard a popping sound around 18:51, during dinner service, and discovered that the lavatory's circuit breakers had tripped. The captain's initial attempt to reset the circuit breakers was unsuccessful.[2]:2 It was not uncommon for a plane's lavatory circuits to pop occasionally, precipitated by a large number of passengers using the toilet after eating, so Cameron waited around eight minutes to give the tripped circuits time to cool down before attempting to reset them again at 18:59. The captain observed that the circuit breakers popped back out as he pushed them.[1][2]:2

At about 19:00, a passenger seated in the last row informed flight attendant Judi Davidson of a strange odor in the rear of the airplane. Davidson traced the odor to the aft lavatory. Davidson attempted to check on the lavatory by opening the door a few inches. At that time she observed the lavatory full of light gray smoke, but did not see flames. Davidson asked flight attendant Laura Kayama to find chief flight attendant Sergio Benetti, who entered the lavatory to investigate.[2]:2

Benetti saw no flames, but did see curls of thick black smoke coming out from the seams around the walls of the lavatory. While Benetti sprayed the interior of the lavatory with a CO2 fire extinguisher, Kayama moved passengers on the sparsely-populated flight forward, and opened air vents to let more fresh air into the cabin. Kayama also went to the cockpit, and at 19:02, informed the flight crew of a "fire in the washroom". Captain Cameron put on his oxygen mask and ordered first officer Ouimet to go back and investigate.[2]:2

Ouimet found that thick smoke was filling the last three to four rows of seats, and he could not reach the aft lavatory. Benetti informed Ouimet that he did not see the source of the fire, but had doused the lavatory with fire retardant. Because smoking was not banned at the time, a regular cause of aircraft lavatory fires was disposal of cigarettes in the lavatory trash bin by passengers smoking in the lavatories, but Benetti told Ouimet that he did not believe the fire was in the trash bin.[2]:3

At 19:04, Ouimet returned to the cockpit, told Cameron about the smoke, and suggested descending. However, Ouimet did not report Benetti's comment that the fire was not a mere trash bin fire. A few seconds later, Benetti came to the cockpit and told the captain that passengers were moved forward and that the smoke was "easing up." Cameron sent Ouimet back to try inspecting the aft lavatory again.[2]:3

At 19:06, while Ouimet was out of the cockpit, Benetti again told Cameron that he thought the smoke was clearing. The captain, still believing the fire was in the lavatory trash bin, had not started descending because he expected the fire would be put out.[2]:3 Shortly after, the "master caution" light in the cockpit illuminated, indicating a loss of main bus electrical power. The captain called the air traffic controller (ATC) in Indianapolis, Indiana, and notified them that Flight 797 had an "electrical problem." Flight 797's transponder signal then disappeared from ATC radar displays; ATC was able to monitor the flight by switching to primary radar tracking.[2]:4

At 19:07, Ouimet reached the aft lavatory again. He reached to open the door, but because it felt hot to the touch, he decided not to open it. Ouimet directed the flight attendants to keep the lavatory door closed, then returned to the cockpit, where he told Cameron, "I don't like what's happening, I think we better go down, okay?" Cameron detected urgency in Ouimet's voice, which he took to mean an immediate descent was needed.[2]:3

Just after Ouimet returned to the cockpit, the cockpit "master warning" light lit up, warning the pilots of a loss of emergency electrical power. Cameron ordered Ouimet to switch to battery power, but the loss of main and emergency electrical power caused some electrical systems to fail, including power for the horizontal stabilizer. This caused the stabilizer to be stuck in the cruising position.[2]:4 This made controlling the plane's descent extremely difficult and required great physical exertion from the pilot and first officer. In addition, both flight recorders stopped recording at this point.[2]:13–14

Descent

At 19:08, Cameron began an emergency descent and declared "mayday, mayday, mayday" to Indianapolis ATC.[lower-alpha 2] Controllers granted Flight 797 clearance to descend for an emergency landing at Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky International Airport in Boone County, Kentucky, near Cincinnati, Ohio.[2]:4 Because the loss of electrical power had impaired some flight instruments, controllers had to direct Flight 797 to the airport using a "no gyro" approach, with the controller observing Flight 797 on radar and directing the flight to make turns based on radar position and heading.[2]:5

Smoke filled the passenger cabin and entered the cockpit as the plane descended.[2]:7 The PA system also failed, leaving the flight attendants unable to communicate efficiently with the passengers.[1] Nevertheless, attendants were able to move all passengers forward of row 13, and to instruct passengers sitting in exit rows on how to open the doors,[2]:8 a practice that was not standard on commercial airline flights at the time.[1]

Landing and evacuation

At 19:20, Cameron and Ouimet made an extremely difficult landing at Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky International Airport. Four tires blew out during the landing. Once the plane came to a stop, Chief Flight Attendant Sergio Benetti was the first to open the front door of the aircraft, and escaped out that way. The pilots quickly shut the airplane down. The overwing and forward aircraft doors were opened, and slides at the front doors were deployed. 18 passengers and all three flight attendants were able to evacuate using these exits.[2]:8 Opening the doors also caused an influx of air that fueled the fire.[1]

The pilots were unable to go back into the passenger cabin due to the smoke and heat.[2]:8 Ouimet escaped through the co-pilot's emergency window shortly after the plane landed, but Cameron, who was exhausted from trying to keep the plane under control, was unable to move. Firefighters doused Cameron in firefighting foam through Ouimet's window, shocking him back to consciousness; Cameron was then able to open the pilot's emergency escape window and drop to the ground, where he was dragged to safety by Ouimet.[1] Cameron was the last person to make it out of the plane alive.[1]

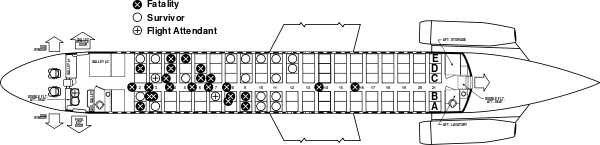

Less than 90 seconds after touchdown, the interior of the plane flashed over and ignited, killing the remaining 23 passengers on board. The passengers trapped inside the plane died from smoke inhalation and burns from the flash fire. Of the 18 surviving passengers, three received serious injuries, 13 received minor injuries, and two were uninjured. None of the five crew members sustained any injuries.[2]:8 Dianne Fadley, a survivor, remarked: "it was almost like anybody who got out had nothing wrong... You made it and you were completely fine, or you didn't make it."[1]

The fire completely destroyed the aircraft.[2]:9 It was noted the unlimited oxygen from the atmosphere fueled the hungry fire, and it ignited with the force of an explosion.

Twenty-one Canadians and two Americans died. Many of the victims' bodies were burned beyond recognition. Almost all of the victims were in the forward half of the aircraft between the wings and the cockpit. Some victims were found in the aisle, while others were still in their seats. Two victims were in the back of the aircraft, even though the passengers were moved forward after the fire had been detected; the disoriented passengers moved beyond the overwing exits and succumbed. Blood samples from the bodies revealed high levels of cyanide, fluoride, and carbon monoxide, chemicals produced by the burning plane.[2]:13–28[1]

Investigation

Because the accident occurred in the United States, it was investigated by the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB).

Although the fuselage was nearly destroyed by the intensity of the fire, the cockpit voice recorder (CVR) and flight data recorder (FDR) were still in good condition and produced vital data for the NTSB investigation.[1] On the CVR, NTSB investigators heard eight sounds of electrical arcing beginning at 18:48. The arcing sounds repeated each time the crew tried to reset the lavatory circuit breakers. Both pilots testified that they did not hear any arcing, and the NTSB concluded that these sounds would be inaudible to the flight crew.[2]:59 Although a number of wires in the lavatory section were later found with insulation stripped away, NTSB investigators were unable to determine whether this insulation damage was the cause of the fire or was caused by the fire.[2]:57

This particular DC-9 had experienced a number of problems over the months leading up to the incident; 76 maintenance reports had been filed in the plane's logs in the previous year,[1] and the CVR records Cameron telling Ouimet to "put [the tripping breakers] in the book there" when the breakers fail to respond to the first reset attempt at 18:52.[4] Cameron attempted once more to reset the breakers at 18:59. The CVR records arcing sounds followed by the popping sound of the breakers continuing to trip again after each reset over the next 60 seconds.[4] Nearly four years earlier, on 17 September 1979, the plane, then serving as Air Canada Flight 680 (Boston, Massachusetts, to Yarmouth, Nova Scotia), had suffered an explosive decompression in the rear bulkhead that required rebuilding the tail section and replacing or splicing most of the wiring and hydraulic lines in the back of the plane; Cameron later noted that the Air Canada maintenance crew "did a heck of a job getting everything put back together" after the decompression incident.[1] Investigators were unable to find signs of arcing in any of the wire splices from the repairs done four years earlier, though much of the wiring in the rear of the plane was severely damaged or destroyed by the fire itself.

Initial findings

The NTSB was ultimately unable to determine the origin of the fire. In August 1984, the NTSB issued a final report which concluded that the probable causes of accident were a fire of undetermined origin, the flight crew's underestimation of the fire's severity, and conflicting fire progress information given to the captain. This report also found that the flight crew's "delayed decision to institute an emergency descent" contributed to the severity of the accident.[5]:71

Aftermath and revised report

Newspapers and other media criticized the actions taken by the crew and said that the pilots took too long to initiate an emergency descent. The NTSB report was especially critical of Cameron for not asking about the exact nature of the fire and not immediately initiating emergency descent when the fire was first reported. Cameron admitted in a press conference following the issuance of the NTSB report that he assumed the problem was a garbage bin fire, a common cause of lavatory fires when smoking was still allowed on flights. "All I know was that I did the best I could," Cameron later said. "I'm very sorry the people that didn't get off, didn't get off, because we spent a lot of time and effort getting them there."[1]

After the NTSB issued its report, a number of commercial pilots and airline personnel petitioned the NTSB to revise its report.[1] In addition, first officer Ouimet sent the NTSB a detailed defense of the crew's actions, including the decision to land in Cincinnati instead of Standiford Field Airport in Louisville, Kentucky, the airport closest to Flight 797 when the crew first declared an emergency. Ouimet stated that Louisville was too close to be able to descend from cruising altitude to an emergency landing safely, and even landing in Cincinnati was a questionable proposition given Cameron's difficulties in controlling the plane.[1]

In January 1986, after reviewing Ouimet's missive and re-evaluating the available data, the NTSB issued a revised version of its accident report.[2] The revised report included Ouimet's explanation of the landing decision. The report was still critical of Cameron's decision not to inquire about the fire itself.[1] However, in its revised report, the NTSB revised its probable cause finding to describe the fire reports given to Cameron as "misleading" instead of merely "conflicting" information. The NTSB also removed the word "delayed" from its description of the pilots' decision to descend, instead listing the "time taken to evaluate the nature of the fire and to decide to initiate an emergency descent" as a contributing factor.[2]:71

The crew of Flight 797 were later honored by multiple Canadian aviation organizations for their heroic actions in landing the plane safely.[6][7] Cameron died from complications of Parkinson's disease on 3 December 2016 in Ottawa, aged 84.[8]

Safety recommendations

As a result of this accident[2] and other incidents of in-flight fires on passenger aircraft, the NTSB issued several recommendations to the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), including:

- Safety Recommendation A-83-70, which asked the FAA to expedite actions to require smoke detectors in lavatories;[1][9]

- Safety Recommendation A-83-71, which asked the FAA to require the installation of automatic fire extinguishers adjacent to and in lavatory waste receptacles;[1][10]

- Strong recommendation that all US-based air carriers review their fire training and evaluation procedures; procedures were to be shortened and focused on taking "aggressive actions" to determine the source and severity of suspected cabin fires while finding the shortest and safest possible emergency descents, including landing or ditching;[1]

- Strong suggestion that passenger instruction in how to open emergency exits become standard practice within the airline industry.[1]

- Strong recommendation for expedited FAA rule changes mandating that all US-based air carriers install (or improve existing) in-cabin fire safety enhancements, including (but not limited to):

- Fire-blocking seat materials to limit both the spread of fire and the generation of toxic chemicals through ignition;

- Emergency track lighting at or near the floor, strong enough to cut through heavy fuel fire smoke;

- Raised markings on overhead bins indicating the location of exit rows to aid passengers in locating these rows in case of passenger visual impairment (either pre-existing or caused by emergency conditions);

- Hand-held fire extinguishers using advanced technology extinguishing agents such as Halon.[2]

Notable passengers

Stan Rogers, a Canadian folk singer, aged 33, was also a victim on the flight. Rogers is known for songs such as "Northwest Passage", "The Mary Ellen Carter" and "Barrett's Privateers". He was going home on Flight 797 after attending the Kerrville Folk Festival in Texas. He died of smoke inhalation.[11]

Aftermath

After this incident, Air Canada sold the right wing of this DC-9 aircraft to Ozark Air Lines to repair a damaged airplane. On 20 December 1983 Ozark Air Lines Flight 650, served by a DC-9 with tail number N994Z,[12] had hit a snow plow in Sioux Falls, killing the snow plow operator and separating the right wing from the aircraft.[13] A wing from C-FTLU was used to replace the one separated on N994Z after the incident. The aircraft was later sold to Republic Airlines, and acquired by Northwest Airlines after Republic merged with Northwest. As of 2012, N994Z was sold for scrap to Evergreen after being assigned to Delta Air Lines, which now owns Northwest Airlines.[14]

Air Canada still uses flight number 797, although it now operates from Montréal–Trudeau International Airport to Los Angeles International Airport with the Airbus A320. [15]

Dramatization

The Discovery Channel Canada / National Geographic TV series Mayday (also called Air Crash Investigation, Air Emergency, and Air Disasters (Smithsonian Channel)) featured the accident in a 2007 episode titled Fire Fight which included interviews with survivors and accident investigators and a dramatic recreation of the flight.[1]

See also

Notes

References

![]()

- "Fire Fight". Mayday. Season 4. 2007. Discovery Channel Canada / National Geographic Channel.

- Aircraft Accident Report: Air Canada Flight 797, McDonnell Douglas DC-9-32, C-FTLU, Greater Cincinnati International Airport, Covington, Kentucky, June 2, 1983 (Supersedes NTSB/AAR-84/09) (PDF). National Transportation Safety Board. 31 January 1986. NTSB/AAR-86/02.

- "Canadian Civil Aircraft Register (C-FTLU)". Transport Canada.

- "CVR transcript Air Canada Flight 797 – 02 JUN 1983". Aviation-Safety.net. 16 October 2004. Retrieved 29 October 2010.

- Aircraft Accident Report: Air Canada Flight 797, McDonnell Douglas DC-9-32, C-FTLU, Greater Cincinnati International Airport, Covington, Kentucky, June 2, 1983 (PDF). National Transportation Safety Board. 8 August 1984.

- Lobsenz, George (10 July 1984). "Air Canada crew criticized in fatal flight". UPI. Retrieved 31 May 2018.

The Air Canada captain and co-pilot were honored by their peers last year when the received the ALPA superior airmanship award for bringing their stricken aircraft to a landing.

- Pigott, Peter (2016). Aviation Pioneers of Canada 7-Book Bundle. Dundurn.

They [the crew] were awarded the Gordon McGregor Trophy by the Royal Canadian Air Force Association,

- "Donald Cameron". Ottawa Citizen. 3 December 2016. Retrieved 13 August 2019.

- "Safety Recommendation A-83-070". www.ntsb.gov. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- "Safety Recommendation A-83-071". www.ntsb.gov. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- "Artist: Rogers, Stan." Canadian Online Explorer. Retrieved on 1 March 2009.

- "FAA Registry (N994Z)". Federal Aviation Administration.

- "National Transportation Safety Board Aircraft Accident/Incident Summary Reports" (PDF). National Transportation Safety Board. 30 September 1985. pp. 17–19. Retrieved 29 October 2010.

- "FAA Registry – Aircraft – N-number Search Results". FAA.gov. Federal Aviation Administration. Retrieved 29 October 2010.

- "Air Canada (AC) #797 ✈ FlightAware". FlightAware. Retrieved 7 December 2019.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Air Canada Flight 797. |

- First NTSB accident report

- Second NTSB accident report (supersedes the first accident report) (Alternate)

- NTSB brief DCA83AA028

- Accident description at the Aviation Safety Network

- A photo of the burning airliner at Airliners.net

- A photo of the accident aircraft at the Aviation Safety Network

- ATC recording on YouTube