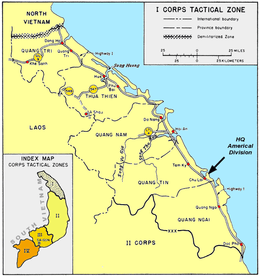

1965 in the Vietnam War

In 1965, the United States rapidly increased its military forces in South Vietnam, prompted by the realization that the South Vietnamese government was losing the Vietnam War as the communist-dominated Viet Cong gained influence over much of the population in rural areas of the country. North Vietnam also rapidly increased its infiltration of men and supplies to combat South Vietnam and the U.S.. The objective of the U.S. and South Vietnam was to prevent a communist take-over. North Vietnam and the insurgent Viet Cong sought to unite the two sections of the country.

| 1965 in the Vietnam War | |||

|---|---|---|---|

US Army soldiers disembarking from helicopters in the Ia Drang Valley | |||

| |||

| Belligerents | |||

|

Anti-Communist forces: |

Communist forces: | ||

| Strength | |||

|

US: 184,314 [1] South Vietnam: 514,000 (including militia) | |||

| Casualties and losses | |||

|

US: 1,928 killed South Vietnam: 11,242 killed.[2] | North Vietnam: 26,000 - 35,000 killed (approximately) | ||

Political instability and internal dissent continued to plague the government of South Vietnam, although in June General Nguyễn Văn Thiệu and Air Marshall Nguyễn Cao Kỳ took control of the country and remained in power for the remainder of the year. In the United States, a majority of Congress and the people supported U.S. participation in the war, although protests against the war became larger and more frequent, especially among college students.

The U.S. began bombing North Vietnam in March, in Operation Rolling Thunder. The U.S. Army and Marines began ground operations to ferret out and defeat the communist forces. General William Westmoreland commanded U.S. forces in South Vietnam. Westmoreland's strategy was attrition, employing U.S. superiority in firepower, technology, and mobility. The usual military tactic of the United States was search and destroy operations in which large U.S. and South Vietnamese units, supported by air and artillery, swept through an area to attempt to engage the communists in battle. North Vietnam and the Viet Cong, by contrast, relied on hit-and-run operations and ambushes, avoiding set-piece battles except at their own initiative.

In November, the U.S. and North Vietnamese armies met head-on for the first time in the Battle of Ia Drang. Both sides claimed victory. The U.S. inflicted heavy casualties on the North Vietnamese, but the battle vindicated the conviction by North Vietnam that its military could slowly grind down the U.S.'s commitment to the war.

South Korea contributed an army division to South Vietnam, while Australia, New Zealand and other countries provided smaller numbers of soldiers. North Vietnam received military aid from the Soviet Union and China.

At year's end, President Lyndon Johnson declared a temporary halt to the bombing of North Vietnam and undertook a diplomatic initiative to seek negotiations with North Vietnam. North Vietnam, on its part, aimed to achieve a decisive military victory, but prepared also for an expanded war if the U.S. continued to escalate its involvement.

Most of the reports and conversations mentioned below were secret and not made public for many years. They reflect the ongoing debate among American officials, military leaders, and the American people about the scope and character of American intervention in the Vietnam War.

January

- 1 January

The South Vietnamese security forces, including regulars, part-time militia, Montagnard irregulars, and National Police totaled 567,246 personnel.[3] 23,310 U.S. military personnel were in South Vietnam.[4]

The number of Viet Cong guerrillas and North Vietnamese regulars in South Vietnam was a matter of much debate. One U.S. government estimate was that the Viet Cong army consisted of 40,000 full-time fighters and 80,000 to 100,000 part-time guerrillas.[5] The Department of Defense's fact book estimated that the Viet Cong numbered less than 200,000 plus 39,175 political cadre.[6] These numbers presumably included thousands of fighters and cadre infiltrated from North Vietnam during the previous five years. The first North Vietnamese army units dispatched to South Vietnam, consisting of three regiments (about 5,000 men), had arrived in South Vietnam in late 1964.[7]

A junior-level CIA analyst, Samuel A. Adams, had just begun work estimating Viet Cong numbers; he would later conclude the U.S. Military Assistance Command Vietnam (MACV) underestimated Viet Cong strength by about one-half.[8]

Both North Vietnam and the United States would rapidly increase the number of their troops in South Vietnam during 1965.

- 2 January

The Battle of Binh Gia concluded. The Viet Cong withdrew from the battlefield. In six days of fighting, the Viet Cong had killed 201 of South Vietnam's best soldiers and five American advisers.[9]

- 3 January

Senator Mike Mansfield, considered the U.S. Congress's most knowledgeable person about Vietnam, appeared on television and said that neutralization of South Vietnam through an agreement reached by negotiations between the U.S. and the communist powers might be the best solution to the Vietnam War. Mansfield was one of several senators who had doubts about the course of U.S. policy in South Vietnam.[10]

- 6 January

The U.S. Ambassador in South Vietnam General Maxwell Taylor summed up the situation in a telegram to the U.S. government in Washington. "We are faced here with a seriously deteriorating situation characterized by continued political turmoil, irresponsibility and division within the armed forces, lethargy in the pacification program, some anti-US feeling which could grow, signs of mounting terrorism by VC directly at US personnel and deepening discouragement and loss of morale throughout SVN. Unless these conditions are somehow changed and trends reversed, we are likely soon to face a number of unpleasant developments ranging from anti-American demonstrations, further civil disorders, and even political assassinations to the ultimate installation of a hostile govt which will ask us to leave while it seeks accommodation with the National Liberation Front and Hanoi."

Taylor opposed the introduction of U.S. ground units to help fight the Viet Cong (as proposed in frustration by President Johnson a few days earlier), endorsing instead a U.S. policy of graduated air attacks against the Ho Chi Minh trail, the supply line for the Viet Cong, and North Vietnam itself.[11]

| Regulars (Army, Air Force, Navy, Marine Corps) | 246,284 |

|---|---|

| Regional Force (RF) | 96,049 |

| Popular Force (PF) | 168, 317 |

| National Police | 31,395 |

| Civilian Irregular Defense Group | 21,454 |

| Coastal Force | 3,747 |

| Total | 567,246 |

- 20 January

While Buddhist protests against the government and the United States intensified, including the burning of a United States Information Service library, Ambassador Taylor met with a Buddhist leader. He said the Buddhists wanted peace and told Taylor that the leaders of South Vietnam were only interested in the benefits they could derive personally from American aid and would otherwise capitulate to the Viet Cong. The Buddhists had been protesting against the government of South Vietnam for the previous two years.[12]

- 26 January

In a speech, former Vice President Richard Nixon argued the U.S. military effort should be escalated to destroy communist supply lines and staging areas in Laos and North Vietnam. He said the U.S. must "either get out, surrender on the installment plan through neutralization, or... find a way to win."[13]

- 27 January

Amidst continuing political chaos in South Vietnam, General Nguyễn Khánh and the Armed Forces Council overthrew the civilian government of Trần Văn Hương in a bloodless coup, replacing Houng with civilian Nguyễn Xuân Oánh. Khánh, who had been Prime Minister during most of 1964, had been hovering in the background for some time, so the coup d'état was not a great surprise. Ambassador Taylor cabled Washington that Khánh had an alliance with the Buddhist Institute headed by Thích Trí Quang. Taylor said, "The most sinister aspect of this affair is the obvious danger that the Buddhist victory may be an important step toward the formation of a government which will eventually lead the country into negotiations with Hanoi and the National Liberation Front."[14]

In response to the coup, National Security Council director McGeorge Bundy and Secretary of State Robert McNamara wrote a memo to President Johnson. They gave the President two options: use American military power to defeat the insurgency, or negotiate thus attempting to "salvage what little can be preserved." McBundy and McNamara favored the first option; Secretary of State Dean Rusk disagreed. Johnson accepted the military option and sent a telegram to Ambassador Taylor in Saigon saying "the U.S. will spare no effort and no sacrifice in doing its full part to turn back the Communists in Vietnam." President Johnson had crossed the Rubicon.[15]

February

- 7 February

The Viet Cong attacked Pleiku airbase (aka Camp Holloway Airfield). Viet Cong demolition teams infiltrated the compound where American advisers were living and, supported by mortar fire, killed eight Americans, wounded 128, and damaged or destroyed 24 American aircraft. McGeorge Bundy (visiting in Vietnam) and General William Westmoreland (commander of the Military Assistance Command Vietnam, or MACV) visited Pleiku that day. Bundy strongly recommended a reprisal attack against North Vietnam.[16] Bundy reported to Johnson "The situation in Vietnam is deteriorating and without new U.S. action defeat appears inevitable--probably not in a matter of weeks or perhaps even months, but within the next year or so.... There is still time to turn it around, but not much."[17]

In retaliation, President Johnson ordered Operation Flaming Dart: forty-nine retaliatory sorties by American and South Vietnamese pilots targeted North Vietnamese army bases near Đồng Hới; a second wave targeted Viet Cong logistics and communications near the DMZ. Among the pilots was Air Marshal Nguyễn Cao Kỳ, a member of Vietnam's ruling Armed Forces Council. Poor weather limited the damage caused by the strikes. One plane and its pilot were lost.[18]

The Premier of the Soviet Union, Alexei Kosygin, was visiting Hanoi during the bombing. The Soviets were furious that an American attack was carried out while Kosygin was present and motivated to provide additional assistance to North Vietnam.[19]

Bundy sent a memorandum to President Johnson advocating "a new US action" without which "defeat seems inevitable." McBundy said that "any negotiated US withdrawal today would mean surrender on the installment plan."[20]

- 10 February

Viet Cong sappers blew up a hotel used as an enlisted men's barracks in Qui Nhơn, a coastal city of South Vietnam, killing 23 American soldiers.[21] In response, President Johnson ordered Flaming Dart 2: 155 sorties and air strikes in North Vietnam by American and South Vietnamese pilots.[22]

In Hanoi, Soviet Premier Kosygin announced the Soviet Union had agreed to assist North Vietnam to defend itself from air attacks, by providing surface-to-air missiles (SAMs), jet fighter planes, technical support and advisers.[23]

- 13 February

President Johnson approved Operation Rolling Thunder, the Joint Chiefs of Staff plan for the sustained bombing of North Vietnam. Over an eight-week period, U.S. warplanes planned to bomb fixed targets and interdict military traffic along roads in southern North Vietnam. Johnson did not immediately launch Rolling Thunder.[24]

- 16 February

In the Vung Ro Bay Incident, an American pilot spotted a 100-ton North Vietnamese naval trawler unloading munitions on a beach at a remote bay on the coast of central South Vietnam. South Vietnamese aircraft sank the ship and the defenders and crew were later killed or captured after a firefight with South Vietnamese naval commandos. The incident spurred further U.S. Navy involvement in the Vietnam War.

The Armed Forces Council of South Vietnam appointed medical doctor Phan Huy Quát as Prime Minister.[25]

- 17 February

On the United States Senate floor, Senator Frank Church said "The Saigon government is losing its war, not for lack of equipment, but for lack of internal cohesion" and the best solution would be the negotiation of a neutral South Vietnam. Church's speech was supported by several other prominent Democratic Party Senators, including George McGovern. Church's call for a neutral South Vietnam echoed similar statements by French President Charles de Gaulle, the Pope, and the Secretary General of the United Nations. Former President Eisenhower and several Republicans supported Johnson's policy. Eisenhower advised Johnson not to negotiate from weakness.[26]

- 18 February

Influential columnist Walter Lippman in The Washington Post said escalation of the Vietnam War would be a disaster. "For this country to involve itself in such a war in Asia would be an act of supreme folly."[27]

- 19 February

General Phạm Ngọc Thảo mounted a coup d'état to overthrow General Khánh, head of the Armed Forces Council. The coup failed. North Vietnam later revealed that Thao was a communist agent.[28]

- 22 February

General William Westmoreland, commander of MACV, requested that two battalions of United States Marines be assigned to protect the airbase at Da Nang from the increasing threat of attacks by the Viet Cong.[29]

- 25 February

General Khánh departed South Vietnam. He was persuaded to leave by his fellow generals and by Colonel Wilson of MACV. Air Marshall Nguyễn Cao Kỳ became the de facto leader of South Vietnam.[30]

- 26 February

The first South Korean troops arrived in South Vietnam.[31] The number of South Korean troops in South Vietnam would total 49,755 by 1969. The U.S. paid most of the cost of the deployment of the Koreans and provided economic incentives to South Korea for its support of South Vietnam.[32]

March

- 1 March

Ambassador Taylor met with generals Nguyễn Văn Thiệu and Trần Văn Minh in Saigon to request permission for the assignment of the Marines to Da Nang airbase. The generals raised no objections, but asked that the Marines arrive "in the most inconspicuous way feasible."[33]

- 2 March

Operation Rolling Thunder was launched. 104 U.S. fighter-bombers and 19 South Vietnamese aircraft hit targets in the largest U.S. bombing raid to date against North Vietnam. Five U.S. planes and one South Vietnamese plane were shot down. The operation was meant to last eight weeks, but instead lasted more than three years.[34]

Previously, North Vietnam and its allies China and the Soviet Union had indicated a willingness for negotiations leading to the neutralization of South Vietnam and the withdrawal of the U.S. The bombing resulted in a hardened and less flexible communist position. North Vietnam shut down channels it had with Canada and France for exploring negotiations.[35]

- 6 March

McGeorge Bundy wrote a memo to President Johnson saying: "Last night, Bob McNamara said for the first time what many others have thought for a long time -- that the Pentagon and the military have been going at this thing the wrong way round from the very beginning: they have been concentrating on military results against guerrillas in the field, when they should have been concentrating on intense police control from the individual villager on up."[36]

- 8 March

Two battalions of U.S. Marines began to land on beaches near Da Nang. The arrival of the Marines heralded the direct involvement of American combat units in the Vietnam War. The Marines had the responsibility of guarding the Da Nang airbase but were ordered to "not, repeat not, engage in day-to-day actions against the Viet Cong." By the end of March the Marines at Da Nang numbered almost 5,000[37]

- 10 March

In Washington, Assistant Secretary of Defense John McNaughton sent a memo to National Security Adviser McGeorge Bundy outlining the U.S. objectives in South Vietnam in percentage terms: "70% -- to avoid a humiliating US defeat...; 20% -- to keep SVN [South Vietnam]...territory from Chinese hands; 10% -- to permit the people of SVN to enjoy a better, freer way of life.[38]

- 12 March

Vice President of the United States Hubert Humphrey had dinner with the Ambassador of the Soviet Union Anatoly Dobrynin in Washington. Dobrynin asked why the U.S. bombed North Vietnam while the Premier of the USSR, Alexei Kosygin was visiting Hanoi. The USSR, said Dobrynin, was now committed to the support of North Vietnam. He said, "We can't be a leader and stand by and ignore the bombing of the North Vietnamese."[39]

- 17 March

The CIA and Defense Intelligence Agency issued an estimate of military strength in South Vietnam. The armed forces of South Vietnam numbered 567,000, of which 245,000 belonged to the regular army (ARVN) and the remainder to the Regional and Popular militia forces. The Viet Cong was estimated to number between 50,000 and 60,000 regulars and 100,000 militia.[40]

- 24–25 March

The first Teach-in to protest the Vietnam War was held at the University of Michigan. 3,500 people attended.[41][42]

- 25 March

China announced that it was ready to "send its personnel to fight together with the Vietnamese people to annihilate the American aggressors."[43]

- 26 March

The commander of MACV, General Westmoreland, said in a report to Washington that the South Vietnamese armed forces had "begun to show evidence of fragmentation and there is no longer an effective chain of command."[44]

- 29 March

In the face of disagreement among U.S. military leaders about where and how many U.S. combat troops should be stationed in Vietnam, Secretary McNamara, MACV commander Westmoreland, Ambassador Taylor, and the Joint chiefs met in Washington. The Chiefs and Westmoreland wanted two U.S. combat divisions sent to Vietnam along with one combat division from the Republic of Korea. Taylor disagreed. McNamara didn't take a position. In meetings the next day, President Johnson agreed only to the assignment of two additional U.S. combat battalions to South Vietnam, but he approved an expansion and extension of the bombing of North Vietnam under operation Rolling Thunder.[45]

- 30 March

Terrorists exploded a car bomb in front of the American Embassy in Saigon killing 22 people, including 2 Americans.[46]

April

In North Vietnam Ho Chi Minh decreed a new military service law. Enlistments were extended indefinitely for soldiers, previously discharged soldiers were recalled, and an increased number of young people were inducted into military service. During 1965, North Vietnam expanded the size of its army by 290,000 personnel and its self-defense militia from 1.4 million to 2.0 million.[47]

- 7 April

President Johnson made a major televised speech at Johns Hopkins University. Johnson described the Vietnam War as an attack by North Vietnam on South Vietnam. He proposed "unconditional discussions" to exchange views with interested parties in search of a peaceful solution, but offered no concessions. Johnson also proposed a massive program to develop the Mekong River basin which could include North Vietnam among the recipients of the Tennessee Valley Authority-type project. Ho Chi Minh responded that the United States must withdraw from South Vietnam as a condition for a peace agreement.[48]

The Johns Hopkins speech marked a change in American policy. Formerly, over a period of several years of escalating warfare in South Vietnam, the U.S. had refused to consider talking to the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese until the U.S. and South Vietnam had gained a military advantage.[49]

- 8 April

North Vietnamese Prime Minister Phạm Văn Đồng responded to President Johnson's proposal for peace negotiations by announcing North Vietnam's Four Points peace formula: withdrawal of all U.S. forces from South Vietnam, neutralization of both Vietnams pending reunification, adoption of the program of the National Liberation Front (Viet Cong) for internal affairs, and reunification without foreign interference.[50]

- 9 April

At a CINCPAC meeting in Hawaii, the planners recommended the deployment of two brigades to South Vietnam. One would be stationed at Biên Hòa near Saigon to protect the airfield there; the other would go to Nha Trang to prepare for the introduction of a full division of American troops. Ambassador Taylor had not been present at the meeting and he protested that "Recent actions relating to the introduction of U.S. ground forces have tended to create an eagerness in some quarters to deploy forces into SVN (South Vietnam) which I find difficult to understand." Taylor opposed the introduction of American ground troops for offensive operations, believing they should be restricted to coastal "enclaves." General Westmoreland disagreed, believing that enclaves were "an inglorious, static use of U.S. forces....that would leave the decision of when and where to strike to the enemy."[51]

- 17 April

In Washington, D.C. about 20,000 people gathered to protest the Vietnam War. This was the first large protest against the war in the United States.[52]

China rescinded the order to its air force to not attack American war planes violating Chinese air space. Over the next three years, 12 American war planes and several reconnaissance planes were shot down over China.[53]

- 20 April

In a meeting in Hawaii, Ambassador Taylor finally agreed to the introduction of U.S. combat ground forces into South Vietnam. In a memo to the President the next day, Secretary of Defense McNamara described the military consensus that "it would take more than six months, perhaps a year or two to...break the will of the DRV/VC [North Vietnam and the Viet Cong] by denying them victory." On this date the U.S. had 33,000 U.S. military personnel in Vietnam and another 20,000 scheduled to be there.[54]

- 23 April

Ambassador Taylor reported to Washington that Prime Minister Quat was reluctant to accept the assignment of more U.S. soldiers to South Vietnam.[55]

- 30 April

The CIA warned in a memorandum that the introduction of U.S. ground forces into Vietnam might result in "constant danger that the war weary people of South Vietnam will let the U.S. assume an even greater share of the fighting.[56]

- Late April

The U.S. Army Chief of Staff General Harold K. Johnson lunched with Vietnam expert and author Bernard Fall in Washington. Johnson said that, "As a result of my discussions with Dr. Fall, I conclude that I am the victim of appreciable misinformation concerning cliques, claques, and the variety of outlooks and objectives of the diverse elements that comprise the population of Vietnam."[57]

In his search for more reliable information about Vietnam, in June, Johnson appointed a team of military officers to develop "new sources of action to be taken in South Vietnam by the United States and its allies, which, will, in conjunction with current actions, lead in due time to successful accomplishment of US aims and objectives." What came to be called "A Program for the Pacification and Long-Term Development of South Vietnam" (PROVN) would be completed on 1 March 1966.[58]

May

- 4 May

President Johnson requested an additional appropriation of $700 million for the Vietnam War during the remainder of the fiscal year. The request was approved by Congress 2 days later. Johnson indicated that he might have to request additional funds.[59]

- 5 May

Soldiers from the 173rd Airborne Brigade arrived in Vietnam. The brigade would be responsible for providing security to the airbase at Biên Hòa and the port of Vũng Tàu, both near Saigon. This was the first combat unit from the U.S. Army to arrive in Vietnam.[60]

- 6 May

The Armed Forces Council of South Vietnam under General Nguyễn Văn Thiệu dissolved itself leaving in nominal control of the country the civilian Prime Minister Quat.[61]

- 10–15 May

In the Battle of Song Be the Viet Cong overran the capital city of Phước Long Province, about 60 miles north of Saigon. The town was recaptured by the ARVN with U.S. air support but the Viet Cong withdrew in good order and evaded pursuit by the ARVN.[62]

- 13–18 May

President Johnson halted the bombing of North Vietnam under Operation Rolling Thunder in an attempt to induce the North Vietnamese to negotiate a peace agreement. North Vietnam instead said the bombing halt was only "an effort to camouflage American intensification of the war."[62]

- 16 May

North Vietnam's leader Ho Chi Minh met with Chinese leader Mao Zedong in China. Ho said that North Vietnam would "take the main burden of the war by themselves" but requested additional Chinese economic and military support. Mao agreed and they set the ground rules for Chinese assistance: North Vietnamese soldiers would fight the war with Chinese logistical help, but the Chinese would not intervene militarily unless the United States invaded North Vietnam.

Chinese assistance to North Vietnam took three forms: engineers and laborers to build and maintain defense works, airfields and roads, anti-aircraft personnel to defend North Vietnam from air attacks, and military equipment. The total number of Chinese stationed in North Vietnam and dedicated to these tasks was about 160,000 with the first tranche arriving in May 1965.[63]

Twenty-seven American soldiers and four Vietnamese were killed in an accidental explosion at Bien Hoa Airbase. More than 40 airplanes were destroyed.[62]

- 17 May

Presidential adviser and future Secretary of Defense Clark Clifford in a letter to President Johnson said, "I believe our ground forces in South Vietnam should be kept to a minimum, consistent with the protection of our installations and property in that country ... This could be a quagmire. It could turn into an open end commitment on our part that would take more and more ground troops, without a realistic hope of ultimate victory." "Quagmire" would later become a common word use to describe U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War.[64]

- 26 May

Eight hundred soldiers of the Australian Defence Force departed Australia to be deployed to Biên Hòa, a few miles north-east of Saigon. New Zealand announced that it would also send a battalion of soldiers.[65]

- 28 May-1 June

The Battle of Ba Gia or Bãi Xoan in Quảng Ngãi Province began when the Viet Cong ambushed an ARVN battalion. Several hundred soldiers on both sides were killed. The battle highlighted the vulnerability of the ARVN as a military force against the flexible VC.[66]

June

- 7 June

General Westmoreland reported to the Joint Chiefs of Staff that the Viet Cong were stronger than ever and that ARVN was taking heavy casualties and suffering from a high rate of desertions and an unwillingness to take the offensive. Westmoreland said, "I see no course of action open to us except to reinforce our efforts in SVN South Vietnam with additional U.S. or third country forces as rapidly as is practical." He identified U.S. units that could be assigned to South Vietnam that would bring U.S. military strength in the country up to 44 combat battalions.[67]

- 9–13 June

In the Battle of Đồng Xoài, in Phước Long Province about 60 miles northeast of Saigon, the Viet Cong overran the district capital, then withdrew following air strikes and South Vietnamese army reinforcements brought in by U.S. helicopters. ARVN suffered more than 800 casualties including dead, wounded, and missing. The U.S. had 7 killed, 12 missing and presumed dead, and 15 wounded. The Viet Cong lost an estimated 350 men in the ground combat, and more in the air bombardment.[68]

- 11 June

Air Marshall Nguyễn Cao Kỳ and General Nguyễn Văn Thiệu took power in South Vietnam, deposing the government of Prime Minister Quat.[69]

- 12 June

MACV Commander General Westmoreland asked the U.S. Department of Defense for increased authority to undertake offensive operations. He said, "We have reached the point in Vietnam where we cannot avoid the commitment to combat of U.S. ground troops." The Pentagon endorsed Westmoreland's request for additional soldiers which would bring the total of American military personnel in Vietnam up to 117,000, plus 20,000 third-country troops, by November 1.[70]

- 14 June

General Nguyễn Văn Thiệu was appointed by the military junta as President of South Vietnam.

- 16 June

Senator J. William Fulbright, Chairman of the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations said on national television that the U.S. should negotiate directly with North Vietnam and make "major concessions" to end the Vietnam War. Fulbright's statement was criticized by prominent Republicans; former Vice President Richard Nixon said that negotiations "would be surrender on the installment plan."[71]

- 18 June

Under Secretary of State George Ball wrote a memo to President Johnson stating, "Ever since 1961 -- the beginning of our deep involvement in Vietnam -- we have met successive disappointments. We have tended to underestimate the strength and staying power of the enemy. We have tended to overestimate the effectiveness of our sophisticated weapons under jungle conditions. We have watched the progressive loss of territory to Viet Cong control. We have been unable to bring about the creation of a stable political base in Saigon." Ball advised caution in expanding the U.S. military commitment to South Vietnam.[72]

Under Operation Arc Light, B-52 aircraft were used for the first time in the Vietnam War. Flying out of Andersen Air Force Base, Guam, 27 B-52s dropped 750- and 1,000-pound bombs on a Viet Cong stronghold. Two B-52s were lost in a mid-air collision. An after-action survey found little evidence of Viet Cong casualties.[73]

- 19 June

Air Marshall Nguyễn Cao Kỳ was appointed by the military junta as Prime Minister. With Thiệu as President and Kỳ as Prime Minister the revolving door of rulers that had prevailed in South Vietnam since the overthrow of Ngô Đình Diệm in November 1963 ended.

- 20 June

After being ambushed while in support of a rescue operation, Douglas A-1 Skyraider pilots Clinton Johnson and Charles Hartman shoot down a North Vietnamese MiG-17 with their 20 mm M3 cannons. This is the first air-to-air gun kill of the Vietnam War.

- 24 June

General Westmoreland advised Washington that he needed more American soldiers than those previously approved and proposed that the U.S. bomb the railroad from North Vietnam to China, mine Haiphong harbor, and carry out B-52 strikes.[74]

- 28–30 June

A battalion of the 173rd Airborne brigade undertook the first major U.S.-led search and destroy mission of the Vietnam War. ARVN and Australian soldiers also participated in the sweep through part of Zone D, about 40 miles northeast of Saigon. The assault began with an artillery barrage; it located very few Viet Cong.[75]

An observation of an Australian on the operation was: "Our patrols do not fire off ammo or shoot up flares like the Yanks--they listen and move quietly, we haven't fired a shot or sent up a flare yet. The Americans think we are mad. It seems to me though, that all they're doing is letting the Viet Cong know where they are. I guess we have a bit to teach them." The Australians had experience in jungle warfare in the Malayan Emergency.[76]

July

- 1 July

Undersecretary of State George Ball dissented from the buildup of American forces in South Vietnam. He wrote President Johnson that "The Viet Cong -- while supported and guided from the North -- is largely an indigenous movement" and that "although we have emphasized its Cold War aspects, the conflict in South Vietnam is essentially a civil war within that country." Ball's view conflicted with the official view that the insurgency in South Vietnam had been created and was sustained by North Vietnam.[77]

- 6–9 July

After B-52 strikes, the U.S. 173rd Airborne began another sweep through Zone D with 2,500 men and ARVN and Australian participation. The allies claimed to have inflicted 100 Viet Cong casualties.[78]

- 8 July

Maxwell Taylor resigned as U.S. Ambassador to South Vietnam. Taylor had earlier been opposed to the introduction of U.S. ground troops into South Vietnam, proposing instead an intensified air campaign against North Vietnam. Taylor would be replaced by Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr., who returned to Saigon for his second stint as ambassador.[79]

- 10 July

The New York Times reported that the 173rd Airborne suffered 10 killed and 42 wounded on its sweep through Zone D, and that its estimates of Viet Cong casualties were inflated. The newspaper reported that the U.S. had begun "to accept aerial estimates of enemy casualties. The command has also begun to calculate probable damage inflicted on the Viet Cong despite the absence of bodies or weapons."[80]

- 12 July

The 2nd Brigade of the U.S. 1st Infantry Division began to arrive in South Vietnam. The brigade was initially responsible for providing security for Bien Hoa Air Base near Saigon.[81]

- 16 July

Secretary of Defense McNamara, visiting South Vietnam, was briefed by MACV commander General Westmoreland. Westmoreland said that U.S. airstrikes had not succeeded in halting the flow of military supplies down the Ho Chi Minh trail. To defeat the Viet Cong, now reinforced by the North Vietnamese Army, would require another large influx of U.S. soldiers amounting to 57 battalions plus helicopter companies and support units. Westmoreland said he planned to reverse the deteriorating military situation by the end of 1965, take the offensive in 1966, and destroy the Viet Cong and capture their strongholds by the end of 1967.[82]

- 20 July

McNamara returned to Washington and recommended to President Johnson that the number of U.S. troops in South Vietnam be increased to 175,000. He recommended also that 235,000 soldiers in the Reserve and National Guard be activated and that the number of U.S. military personnel be increased by 375,000. He recommended also that air strikes against North Vietnam be increased from 2,500 to 4,000 per month.[83]

On the 11th anniversary of the signing of the Geneva Accords ending the First Indochina War, North Vietnamese leader Ho Chi Minh said that the North Vietnamese and the Viet Cong will fight for 20 years or more to achieve victory and unification of the two Vietnams.[84]

- 21 July

Members of the New Zealand armed forces were deployed to South Vietnam.[85]

- 22 July

President Johnson met with his top military advisers. In the course of the discussion, General Wallace M. Greene, Jr. estimated that winning the Vietnam War would take 5 years and 500,000 American soldiers. He said that he believed the American people would back such a commitment. Johnson was skeptical that Americans would support such a large commitment and opted instead for a gradual buildup of American forces and escalation of the war as recommended by General Westmoreland, the commander of U.S. forces in Vietnam.[86]

- 24 July

The first surface-to-air missile (SAM) fired by North Vietnam brought down a U.S. F-4C Phantom jet. The SAM site that fired the missile was one of five ringing Hanoi at a distance of about 20 miles (32 km).[87]

- 27 July

In a meeting with President Johnson most Congressional leaders of both parties agreed with his plan to increase U.S. military forces in South Vietnam. The exception was Senator Mike Mansfield, while publicly supporting the President said at the meeting, said, "we are going deeper into a war in which even a total victory would, in the end, be a loss to the nation." Mansfield proposed negotiations to end the war.[88]

- 28 July

President Johnson ordered an increase in the number of U.S. troops in South Vietnam to 125,000 and an increase in the draft of young Americans into the military from 17,000 to 35,000 per month, but he declined to activate the Reserve and National Guard. Johnson's announcement represented a quantum leap in the American commitment and was followed quickly by massive increases in the number of U.S. troops deployed to South Vietnam.[89]

- 29 July

A brigade of the 101st Airborne Division arrived at Cam Rahn Bay and set up its base camp there.

August

Sixty-one percent of Americans responded "no" to the following question by the Gallup Poll, "Do you think the U.S. made a mistake sending troops to fight in Vietnam?"[90]

- 3 August

A company-sized U.S. Marine sweep through the village of Cam Ne was publicized in the U.S.. A Marine was shown on television lighting an old woman's house while she pleaded for him to stop. The Marines said that the village had been fortified by the Viet Cong.[91]

- 5 August

The Viet Cong attacked a petroleum storage facility near Da Nang, destroying 40 percent of the facility and almost 2 million gallons of fuel.[92]

Former General and Ambassador Maxwell Taylor, now an adviser to President Johnson, told the President: "By the end of 1965, the North Vietnamese offensive will be bloodied and defeated without having achieved major gains." North Vietnam would be forced to change its strategy.[93]

- 6 August

Air Force Colonel Robert Sexton confided to his diary: "The V.C. are hurting but they still control things because we are afraid to get out of our forts on other than temporary patrols or sweeps. We need to devote fully 50% of our effort to psychological operations and civic action."[94]

- 10–17 August

The U.S. Special Forces Civilian Irregular Defense Group (CIDG) camp at Duc Co, 45 kilometres (28 mi) southwest of Pleiku had been under siege by the Viet Cong since June. Attempts by ARVN to lift the siege had failed. General Westmoreland sent the 173rd Airborne brigade to Pleiku and the brigade opened the highway from Pleiku to Duc Co. The Viet Cong (possibly reinforced by a North Vietnamese unit) withdrew.[95]

- 17–24 August

Operation Starlite was the first offensive military action conducted by the U.S. Marines during the Vietnam War and the first purely American operation. Lieutenant General Lewis W. Walt with 5,500 Marines launched a preemptive strike against 1,500 Viet Cong to nullify a threat on the Chu Lai base, 60 miles (97 km) south of Da Nang. The Marines claimed to have killed more than 600 Viet Cong at a loss to themselves of more than 50 dead.[96]

General William E. DePuy at an later briefing said that the Viet Cong "maneuvered in the jungle, maintained tactical integrity, withdrew their wounded, lost practically no weapons, and did a first class job" and that "we'd be proud of American troops...who did as well."[97]

September

- 6 September

The New York Times reported that ex-Vice President Richard Nixon said at a press conference that 125,000 American troops and an expanded bombing campaign would be sufficient to achieve victory in South Vietnam.[98]

- 11 September

The U.S. 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile) began to arrive in South Vietnam at Qui Nhơn. The division was the first full U.S. Army division to be deployed to South Vietnam. 1st Cavalry relied on helicopters to transport its combat units to and from operational areas.[99]

- 13 September

Columnist Joseph Alsop said in The Washington Post said that, with the U.S. military build-up in South Vietnam, "at last there is light at the end of the tunnel."[100]

- 18 September

In Operation Gibraltar, 224 soldiers of the First Brigade of the 101st Airborne landed by helicopter near An Khê, in the Central Highlands area where 2 Viet Cong battalions were located. The Viet Cong attacked and killed 13 Americans. Air strikes forced the Viet Cong to retreat, with losses estimated by the U.S. at between 226 and 257. General Westmoreland called the operation "a great victory." Others, including Col. David H. Hackworth, considered the battle "not... a great victory."[101]

- 20 September

Seven U.S. warplanes were shot down over North and South Vietnam.[102]

- 22 September

General Westmoreland requested 35,000 additional American troops, which would bring the total military personnel authorized in South Vietnam to 210,000. President Johnson and Secretary of Defense McNamara set a limit of the total number of U.S. soldiers of 195,000.[103]

October

- 15 October

David Miller became the first American to burn his draft card as a protest against the Vietnam War. He was arrested by the FBI and later served 22 months in prison.[104]

- 16 October

Protests against the U.S. participation in the Vietnam War took place in Europe and in about 40 U.S. cities. The organization coordinating the U.S. demonstrations was called the National Coordinating Committee to End the War in Vietnam.[105]

- 19–25 October

The Siege of Plei Me was a series of assaults by the North Vietnamese army on a CIDG camp manned by U.S. and ARVN special forces and rangers and 400 Montagnard allies. U.S. airstrikes and a relief force lifted the siege. The siege led up to the Battle of Ia Drang.[105]

- 27 October

A CIA intelligence estimate said that "Hanoi continues to asset its determination to press on with the war in South Vietnam despite the continuing attrition of the air war and the increase of US troops in the South."[103]

November

- 2 November

To protest the Vietnam War, a Quaker named Norman Morrison doused himself in kerosene and set himself on fire in front of The Pentagon. Morrison died.[106]

- 3 November

In a memorandum to President Johnson, Secretary McNamara estimated total communist forces in South Vietnam as having increased to 230,000, including 71,000 Viet Cong main force, 40,000 political cadre, 110,000 guerrillas, and 20,000 North Vietnamese soldiers. McNamara anticipated that these totals would increase.[107]

- 5–8 November

Operation Hump was a search and destroy operation by the 173rd Airborne Brigade, in an area about 17.5 miles north of Biên Hòa. The 1st Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment, deployed south of the Đồng Nai River while the 1st Battalion, 503rd Infantry, conducted a helicopter assault on an LZ northwest of the Đồng Nai and Song Be rivers.

- 8 November

The Battle of Gang Toi was fought between Australian troops and the Viet Cong. The battle was one of the first engagements between the two forces during the war and occurred when the 1st Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment (1RAR) found a Viet Cong bunker system in the Gang Toi Hills, in northern Biên Hòa Province.

A Republic of Korea army division completed its landing in South Vietnam to participate in the Vietnam War.[108] The Korean Division was stationed at Qui Nhơn in Bình Định Province on the central coast of South Vietnam. With the Koreans in Qui Nhơn, a brigade of the U.S. 1st Infantry Division moved inland to protect Highway 19, which led to Pleiku in the Central Highlands. A South Korean Marine Brigade was stationed at the port city of Nha Trang.[109]

- 14–18 November

The Battle of Ia Drang was one of the most consequential battles of the Vietnam War. For the first time, the United States Army and the People's Army of Vietnam (the North Vietnamese Army) met head-on in a major engagement, with the South Vietnamese army and the Viet Cong playing only minor roles. Casualties were heavy on both sides, with some 250 U.S. and at least 1,200 North Vietnamese dead. For General Westmoreland, the battle was a victory for U.S. firepower and mobility in a war of attrition in which the U.S. attempted to kill more communist troops than could be replaced. However, in the words of Joe Galloway, a journalist awarded a Bronze Star for his participation in the battle, Ia Drang was "the battle that convinced Ho Chi Minh he could win." The communists would "grind down the Americans" as they had the French in the 1940s and early '50s in the First Vietnam War.[110]

- 30 November

In the aftermath of the Battle of Ia Drang and after meeting with General Westmoreland in South Vietnam, Secretary of Defense McNamara recommended in a memorandum to President Johnson that the number of U.S. troops in South Vietnam should be increased to about 400,000 in 1966 and possibly by an additional 200,000 in 1967. McNamara estimated that 1,000 Americans per month would die in the war and that "the odds are even" that the U.S. would prevail. McNamara recommended a pause in bombing North Vietnam of 3 to 4 weeks duration to try to find a way to end the war before undertaking the military buildup. Ambassador Lodge, General Westmoreland, and CINCPAC opposed the bombing halt.[111]

December

In an article in Reader's Digest, former Vice President Richard Nixon opposed negotiations to end the Vietnam War. "There can be no substitute for victory when the objective is the defeat of communist aggression", he said.[112]

- 18 December

Operation Game Warden (Task force 116) began. It was a U.S. and South Vietnamese Navy operation in the Mekong Delta and near Saigon to patrol the rivers and coastal waters of South Vietnam, prevent the infiltration of soldiers and supplies from North Vietnam, and deny the Viet Cong access to the waterways.[113]

- ca. 18 December

After a visit to South Vietnam, Marine Corps General Victor Krulak wrote a report expressing disagreement with General Westmoreland's strategy of attrition. It was "wasteful of American lives, promising a protracted, strength-sapping battle with small likelihood of a successful outcome." Krulak proposed instead a focus on a pacification program to provide village security plus increased air strikes.[114]

- 24 December

President Johnson announced a halt in the bombing of North Vietnam and initiated a worldwide diplomatic effort to persuade North Vietnam to negotiate an end to the war. The Department of Defense opposed the bombing halt.[115]

- 27 December

North Vietnamese leader Ho Chi Minh addressed the Communist Party Central Committee in Hanoi. Ho said that "politics" was the weak point of the American and South Vietnamese enemy, and the domestic situation of the United States will not permit the U.S. to utilize its military and economic power in South Vietnam. The Committee decided that the communist forces in South Vietnam should seek a "decisive victory within a relatively short period of time", but must prepare to defend itself if the U.S. expands its war effort.[116]

- 31 December

U.S. military personnel in South Vietnam now totaled 184,314, compared to 23,310 a year earlier.[117] U.S. casualties in 1965 totaled 1,928 dead, compared to 216 in the 1964.[118] South Vietnamese military forces totaled 514,000, including the Army and the Popular Force and Regional Force militias.[119] The South Vietnamese armed forces suffered 11,242 killed in action, a five-fold increase in battle deaths since 1960.[120] 93,000 persons deserted from the South Vietnam's armed forces in 1965.[121]

At year's end, the North Vietnamese army numbered 400,000, compared to 195,000 a year earlier. Air force and air defense capabilities were greatly expanded. 50,000 North Vietnamese cadre and soldiers infiltrated South Vietnam during 1965, equal to the total number infiltrated from 1959 through 1964. Group 559, charged with transporting supplies down the Ho Chi Minh Trail to supply communist troops in both South Vietnam and Laos, was expanded to 24,400 personnel and moved almost as much tonnage south in 1965 as it had in the preceding six years.[122]

Conscription (draft) into the United States armed forces in 1965 was 230,991 men, compared to 112,386 in 1964.[123]

Year in numbers

| Armed Force | Strength | KIA | Reference | Military costs – 1965 | Military costs – 2020 | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 514,000 | 11,242 | [124] | |||||

| 184, 314 [1] | 1,928 | [125] | US$20 billion | US$ 162,259,770,000 | [1] | ||

| 20,620 | [124] | ||||||

| 20 | [124] | ||||||

| 1560 | [124] | ||||||

| 70 | [124] | ||||||

| 120 | [124] | ||||||

| 220,000 |

Notes

- Heinemann 2006, p. 65

- Clarke, p. 275

- Clarke, p. 20

- "Timeline, 1963–1964, http://www.vietnamgear.com/war1963.aspx, accessed 8 Sep 2014

- Clarke, p. 19

- Adams, p. 34

- Asselin, Pierre (2013), Hanoi's Road to the Vietnam War, 1954–1965, Berkeley: University of California Press, p. 200

- Clarke, p. 20; Adams, p. 84

- Logevall, pp. 302-303

- Logevall, pp. 305-306

- FRUS, Document 9

- Logevall, p. 212

- Johns, Andrew L. (June 1999), "A Voice from the Wilderness: Richard Nixon and the Vietnam War, 1964–1966", Presidential Study Quarterly, Vol. 29, No. 2, p, 321. Downloaded from JSTOR.

- Logevall, p. 316

- Logevall, pp. 317-319

- McMaster, p. 215

- Garland, p. 14

- Clodfelter, p. 58; McMaster, p. 218-219

- Gardner, Lloyd C. "Lyndon Johnson and the Bombing of Vietnam: Politics and Military Choices" in The Columbia History of the Vietnam War (2011), New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-13480-4.

- Johns, pp. 329–330

- "Vietnam War Timeline: 1965", http://vietnamgear.com/war1965.aspx

- Clodfelter, p. 58–59

- "Soviet Aid to North Vietnam" http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/vietnam/hist-2nd-indochina-ussr.htm, accessed 11 Oct 2014

- Logevall, pp 333–334

- Moyar, p. 363

- Logevall, pp. 333–350

- Logevall, pp. 351–352

- Moyar, p. 307; Tucker, p. 325

- Shulimson and Johnson, p. 7

- Moyar, p. 364; Logevall, p. 362

- 26 February 1965, http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/first-south-korean-troops-arrive Archived 2015-03-31 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 29 April 2015

- ref.Brueker Remco (2009), "Korea's Forgotten War" Korean Histories, pp. 40–42, www.koreanhistories.org/files/KH1_1%20Breuker-Korea%27s%20Forgotten%20War.pdf, accessed 29 April 2015

- Shulimson and Johnson, p. 9

- Mann, p. 408; McMaster, p. 234

- Logevall, pp. 366-367

- Kaiser, pp. 413-414

- Shulimson and Johnson, pp. 11-16

- McMaster, pp. 236-237

- FRUS, January–June 1965, Document 195

- Krepinevich, Jr., p. 143

- Olson, James Stuart (1999). Historical dictionary of the 1960s. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 26. ISBN 0-313-29271-X.

- Anderson, David L. (2000). The human tradition in the Vietnam era. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 183. ISBN 0-8420-2763-7.

- Chen Jian (June 1995), "China's Involvement in the Vietnam War", The China Quarterly, No. 142, p. 366. Downloaded from JSTOR.

- Moyar, Michael (Oct 2004), "Political Monks: The Militant Buddhist Movement during the Vietnam War", Modern Asian Studies, Vol. 38, No. 4, p. 778

- Krepinevich, Jr., pp. 145-146

- Bowman, p. 110

- Military History Institute of Vietnam, p. 164

- Kaiser, pp. 423-426

- Kaiser, p. 421

- Qiang Zhai, p 25

- Krepinevich, Jr., pp. 140-141, 146-149

- Barringer, Mark "The Anti-War Movement in the United States" http://www.english.illinois.edu/maps/vietnam/antiwar.html, accessed 13 Oct 2014

- Chen Jian, p. 377

- Buzzanco, p. 211

- Buzzanco, p. 213

- Krepinevich, Jr., p. 150

- Sorley, Lewis (2008), "To Change a War: General Harold K. Johnson and the PROVN study", http://strategicstudiesinstitute.army.mil/pubs/parameters/Articles/98spring/sorley.htm Archived 2015-10-05 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 19 Oct 2015

- Birtle, Andrew (October 2008)"PROVN, Westmoreland, and the Historians: A Reappraisal' The Journal of Military History, Vol. 72, p. 1213–1214

- FRUS, Documents 283

- Krepinevich, Jr., pp. 147, 151

- Bowman, p. 114

- Bowman, p. 115

- Chen Jian, pp. 369-374

- FRUS, 1`964-1968, Vol II, Vietnam January--June 1963, Document 307.https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1964-68v02/d307, accessed 19 Oct 2015

- Australia 2010, p. 5; Bowman, p. 116

- Bowman, p. 116

- Kaiser, pp. 440-442

- Bowman, p. 118

- Kaiser, pp. 445-446

- Kaiser, p. 445-446

- Mann 445-446

- Kaiser, pp. 448-449

- "Operation Arc Light" Air Force Historical Studies Office http://www.afhso.af.mil/topics/factsheets/factsheet.asp?id=15262, accessed 2 Oct 2014

- Kaiser, pp 451-452

- Kaiser, p. 454

- Garland, pp. 26-27

- Gilbert, Marc Jason (2002) "The Cost of Losing the 'Other War'" in Why the North Won the Vietnam War,, New York: Palgrave, p. 167

- Bowman, p. 120

- Bowman, p. 120; Mann, p. 395

- Kaiser, pp 454-455

- Garland, pp 33-34

- Buzzanco, p. 220-221

- Buzzanco, p. 221

- Bowman p. 121

- Jessup 1998, p. 523

- Gilbert, p. 167

- Van Staaveren, p. 163

- Mann, p 455-457

- Buzzanco, p. 22; Mann, p. 458

- Lunch and Sperlich, p. 25

- Shulimson and Johnson, p. 64

- Bowman, p. 124

- Mann, p. 464

- Gilbert, p. 193

- Garland, pp. 30-31

- Lehrack, Otto J. "Operation Starlite: The First Battle of the Vietnam War Leatherneck, http://www.military.com/NewContent/0,13190,Leatherneck_050815_Starlite,00.html, accessed 5 Oct 2014

- Buzzanco, p. 234

- Johns, p. 323

- "1st Cavalry Division Arrives in Country" http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/1st-cavalry-division-arrives-in-country

- Adams, pp. 32-33

- Garland, pp 42-43

- Bowman, p. 126

- Mann, p. 468

- Miller, David, "Memoirs of a Draft Card Burner", http://www.reclaimingquarterly.org/82/rq-82-draftcard.html, accessed 13 Oct 2014

- Bowman, p. 127

- "The Pacifists" Time Magazine. November 12, 1965, , accessed June 5, 2007

- FRUS, Vol. 3, Document 189

- Krepinevich, Jr., p. 168

- "ROK Army and Marines prove to be rock-solid fighters and allies in Vietnam War" "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2010-11-28. Retrieved 2009-04-04.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link), accessed 7 Oct 2014

- Krepinevich, Jr., p. 169, Galloway, Joe, "Ia Drang--The Battle That Convinced Ho Chi Minh He Could Win" History Net, 18, Oct 2010, http://www.historynet.com/ia-drang-where-battlefield-losses-convinced-ho-giap-and-mcnamara-the-u-s-could-never-win.htm//

- Buzzanco, pp. 236-237, 243-244

- Johns, p. 324

- Game Warden (CRC 284 – Center For Naval Analyses – Operations Evaluation Group), 01 January 1976, Folder 08, Box 06, Glenn Helm Collection, The Vietnam Center and Archive, Texas Tech University. Accessed 11 Oct. 2014. <http://www.vietnam.ttu.edu/virtualarchive/items.php?item=1070608001>, accessed 11 Oct 2014

- Buzzanco, pp. 249-250

- Mann, pp. 476--477

- Military History of Vietnam, pp 171-172

- "Vietnam War Timeline: 1965" http://www.vietnamgear.com/war1965.aspx, accessed 11 Oct 2014

- "Statistical Information about Fatal Casualties of the Vietnam War" https://www.archives.gov/research/military/vietnam-war/casualty-statistics.html, accessed 11 Oct 2014

- Summers, Jr., p. 36

- Clarke, Jeffrey J. (1988), United States Army in Vietnam: Advice and Support: The Final Years, 1965–1973, Washington, D.C: Center of Military History, United States Army, p. 275

- Fall (1966), p 13. Downloaded from JSTOR.

- Military History of Vietnam, pp. 164-171

- "Selective Service System: Induction Statistics" "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-05-07. Retrieved 2005-12-27.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link), accessed 12 Oct 2014

-

War Remnants Museum Data

Armed Force 1964 1965 1966 1967 1968 1969 1970 1971 1972

514,000 643,000 735,900 798,800 820,000 897,000 968,000 1,046,250 1,048,00053**553(55((3(5(5minute ththhthntththte digest my nuts

23,310 180,000 385,300 485,600 549,500 549,500 335,790 158,120 24,000

200 20,620 25,570 47,830 50,000 48,870 48,540 45,700 36,790 .svg.png)

200 1560 4530 6820 7660 7670 6800 2000 130

0 20 240 2220 6000 11,570 11,570 6000 40

20 70 2060 2020 1580 190 70 50 50

30 120 160 530 520 550 440 100 50 - United States 2010

References

- Adams, Sam (1994), War of Numbers: An Intelligence Memoir South Royalton, Vermont.: Steerforth Press.

- Australia, Australian Defence Force (2010). "Australia in Vietnam" (PDF). Australian Defence Force. Retrieved March 29, 2010.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bowman, John S., ed. (1985), The World Almanac of the Vietnam War, New York: Bison Books. ISBN 0-88687-272-3.

- Buzzanco, Robert (1996), Masters of War: Military Dissent and Politics in the Vietnam Era, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-48046-9.

- Clarke, Jeffrey J. (1988), The United States Army in Vietnam: Advice and Support: The Final Years, 1965–1973, Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History, United States Army.

- Clodfelter, Michael (1995), Vietnam in Military Statistics: A History of the Indochina Wars, 1772–1991. McFarland & Company, 1995. ISBN 0786400277, 9780786400270

- Fall, Bernard (1966), "Viet Nam in the Balance", The Australian Quarterly, Vol 38, No. 4, p. 13

- FRUS. Foreign Relations of the United States, 1964–1968, Vol II, Vietnam, January–June 1965, United States Department of State, http://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1964-68v02

- FRUS Foreign Relations of the United States, 1964–1968, Vol III, Vietnam, June–December 1965, United States Department of State, http://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1964-68v03

- Garland, John M. (2000), Combat Operations: Stemming the Tide, May 1965 to October 1966, Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History, United States Army.

- Heinemann, Larry (2006). Black Virgin Mountain: A Return to Vietnam (2006 ed.). Vintage Books. ISBN 1-4000-7689-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Total pages: 243

- Jessup, John E. (1998). An encyclopedic dictionary of conflict and conflict resolution, 1945-1996 (1998 ed.). Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-313-28112-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Total pages: 887

- Kaiser, David (2000), American Tragedy: Kennedy, Johnson, and the Origins of the Vietnam War, Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-00225-3.

- Krepinevich, Jr., Andrew F. (1986), The Army and Vietnam, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-2863-5.

- Li, Xiaobing (2007). A history of the modern Chinese Army (2007 ed.). University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-2438-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Total pages: 413

- Logevall, Frederik (1999), Choosing War: The Lost Chance for Peace and the Escalation of War in Vietnam Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-52022-919-8.

- Lunch, William L. and Sperlich, Peter W. (1979), "American Public Opinion and the War in Vietnam" The Western Political Quarterly, Vol 32, No. 1, pp. 231–44. Downloaded from JSTOR.

- McMaster, H. R. (1997), Dereliction of Duty: Lyndon Johnson, Robert McNamara, the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the Lies that Led to Vietnam, New York: Harper Perennial. ISBN 0-06-018795-6.

- Mann, Robert (2001), A Grand Delusion: America's Descent into Vietnam, New York: Basic Books. ISBN 0-465-04369-0.

- The Military History Institute of Vietnam (2002) Victory in Vietnam: The Official History of the People's Army of Vietnam, 1954–1975 Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 0-7006-1175-4.

- Moyar, Mark (2006), Triumph Forsaken: The Vietnam War, 1954–1965. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-86911-9.

- Qiang Zhai (1999), "Opposing Negotiations: China and the Vietnam Peace Talks, 1965–1968", Pacific Historical Review, Vol 68, No. 1. Downloaded from JSTOR.

- Shulimson, Jack and Johnson, Major Charles M. (1978), U.S. Marines in Vietnam: The Landing and Building, 1965, Washington: Government Printing Office.

- Summers, Jr., Harry G. (1985), Vietnam War Almanac, New York: Facts on File Publications. ISBN 0-8160-1017-X.

- Tucker, Spencer C., ed. (2000), Encyclopedia of the Vietnam War: A Political, Social and Military History, Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-040-6.

- United States, Government (2010). "Statistical information about casualties of the Vietnam War". National Archives and Records Administration. Archived from the original on 26 January 2010. Retrieved March 6, 2010.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Van Staaveren, Jacob (2002), Gradual Failure: The Air War Over North Vietnam 1965–1966, Washington: Air Force History and Museums Program, United States Air Force.