1964 in the Vietnam War

South Vietnam was in political chaos during much of the year, as generals competed for power and Buddhists protested against the government. The Viet Cong communist guerrillas expanded their operations and defeated the South Vietnamese army (ARVN) in many battles. North Vietnam made a definitive judgement in January to assist the Viet Cong insurgency with men and material. In November, North Vietnam ordered the North Vietnamese Army to infiltrate units into South Vietnam and undertake joint military operations with the Viet Cong.

| 1964 in the Vietnam War | |||

|---|---|---|---|

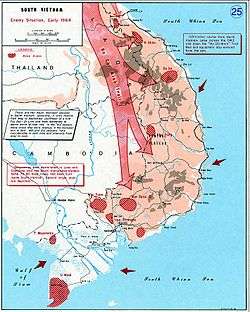

A map of South Vietnam showing provincial boundaries and names and military zones: 1, II, III, and IV Corps. | |||

| |||

| Belligerents | |||

|

Anti-Communist forces: |

Communist forces: | ||

| Strength | |||

|

US: 23,310 (31 Dec 1964) South Vietnam: 514,000 (includes militia)[1] | NVA/VC:100,000 [2] | ||

| Casualties and losses | |||

|

US: 216 killed South Vietnam: 7,457 killed[3] | North Vietnam:16.785 killed | ||

The new President of the United States, Lyndon Johnson, and his civilian and military advisers wrestled with the problem of a failing government in South Vietnam and military gains by the communists. In August, an attack on American navy vessels caused Johnson to seek and gain U.S. congressional approval of the Tonkin Gulf Resolution, which authorized him to use military force if necessary to defend South Vietnam. Throughout the year, there were calls from many quarters—American, foreign, and South Vietnamese—for the United States to negotiate an agreement for the neutralization of South Vietnam, which they refused to consider.

Many of President Johnson's advisers advocated an air war against North Vietnam and the introduction of U.S. combat troops into South Vietnam. By year's end, the 23,000 U.S. military personnel in South Vietnam were still technically "advisers" (although they participated in many air and ground operations with the ARVN), but Johnson was contemplating U.S. ground troops.

At the time, most of the reports and conversations mentioned below were secret; they were not made public for many years.

January

- 10 January

U.S. Ambassador to South Vietnam Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. reported to Washington that the new President of South Vietnam Dương Văn Minh told him that he opposed American soldiers going into villages and districts of rural Vietnam as they would be perceived as "more imperialistic than the French" and would give credence to communist propaganda that the Saigon government was a lackey of the United States.[4]

- 14 January

Theodore Sorensen, one of former President Kennedy's most trusted aides, wrote President Johnson to oppose the neutralization of South Vietnam as proposed by French President Charles de Gaulle and others. Sorensoen said neutralization would result in a communist takeover of South Vietnam, weaken the U.S. position in Asia, and cause political problems for the Democratic Party. Johnson's principal advisers—Dean Rusk, Robert McNamara, McGeorge Bundy, and Walter Rostow—echoed Sorensen's views. (In December, Senator Mike Mansfield had proposed negotiation of a neutral South Vietnam.[5])

- 20 January

The Central Committee of the Communist Party of North Vietnam adopted Resolution 9. The secret resolution declared all-out war on South Vietnam to defeat the South Vietnamese army (ARVN) before the United States could introduce a large number of American soldiers into the war. The Resolution estimated that American soldiers participating in the war would not exceed 100,000. The Americans "clearly understand that if they get bogged down in a large-scale protracted war, then they will fall into an extremely defensive position internationally." Diplomacy would be expanded to gain "the sympathy of antiwar groups in the United States" and other people around the world. Finally, the Resolution called for a purge of party members in North Vietnam who had emphasized socialistic development in North Vietnam rather than North Vietnamese help for the "liberation" of the South.

Resolution 9 was the most important Communist party decision on action in South Vietnam since the Geneva Accords of 1954, which had provisionally separated North and South Vietnam pending national elections (never held, due to opposition by the government of South Vietnam).[6]

With the adoption of Resolution 9, party moderates such as Ho Chi Minh and Võ Nguyên Giáp were marginalized, and militant leaders such as Lê Duẩn and Lê Đức Thọ took command of the Communist Party and North Vietnam.[7]

- 30 January

General Nguyễn Khánh led a successful coup ousting the military junta led by General Dương Văn Minh from the leadership of South Vietnam. It came less than three months after Minh's junta had come to power in a coup d'état which overthrew and killed then President Ngô Đình Diệm. The coup was bloodless and lasted only a few hours.

- 31 January

Journalist James Reston in The New York Times called for the U.S. to seek a negotiated settlement to the war in South Vietnam. Reston's view echoed that of French President Charles de Gaulle who was advocating that negotiations begin to make South Vietnam a neutral country[8]

February

- 1 February

The United States Senate Majority Leader Mike Mansfield told President Johnson that the overthrow of the Minh government was unlikely to result in "significant improvement in the situation" in South Vietnam. Mansfield said the coup was "likely to be only the second in a series as military leaders, released from all civilian restraint, jockey for control of the power which resides in United States aid."[9]

- 3 February

The new leader of South Vietnam, General Khánh, reversed an earlier decision by Minh by giving his approval to the assignment of additional American military and civilian advisers and authorizing U.S.-directed covert operations in North Vietnam under OPLAN 34.

- 17 February

David Nes, the Deputy Chief of Mission of the American Embassy in Saigon, wrote a pessimistic memorandum to Ambassador Lodge and senior officials in Washington. Nes did not see much prospect for the improvement of South Vietnamese performance. He said that escalation of the U.S. military effort might be the only alternative to the neutralization of South Vietnam as proposed by de Gaulle and others.[10]

- 26 February

The Battle of Long Dinh involved the People's Liberation Armed Forces (Viet Cong) and the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN). ARVN, despite overwhelming numbers and firepower, was not aggressive in its attack and the Viet Cong escaped.

March

- 4 March

President Johnson met with the Joint Chiefs of Staff. The Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Maxwell Taylor recommended a "progressive and selective attack on targets in North Vietnam." Johnson, however, disagreed, saying that "he did not want to start a war before November" because of the impact an expanded war might have on the Presidential elections that month.[11]

- 16 March

Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara wrote a memo to President Johnson after returning from his most recent visit to South Vietnam. McNamara said that up to 40 percent of South Vietnam was now controlled by the Viet Cong, the Khánh government was ineffective, the South Vietnamese apathetic, and the Americans in South Vietnam frustrated. He recommended that the U.S. finance a 50,000 man increase in the size of the South Vietnamese army (ARVN). He also recommended that the U.S. air force be prepared to initiate bombing of North Vietnam. Johnson approved the plan and directed its implementation.[12]

- 26 March

Senator Wayne Morse was the only prominent American politician to oppose publicly American military involvement in South Vietnam. Morse strongly disagreed with McNamara's assessment of the situation in Vietnam. To refute McNamara's contention that the U.S. was fighting communism in South Vietnam, Morse said, "There are no Chinese soldiers in South Vietnam. There are no Russian soldiers in South Vietnam. The only foreign soldiers in South Vietnam are U.S. soldiers."[13]

April

- 4 April

Former Vice President Richard Nixon said that President Johnson's plans to defeat the communists in South Vietnam "may be inadequate." He said that a visit to South Vietnam had persuaded him that "Johnson's Vietnam policy would not succeed."[14]

- 19 April

At a meeting in Saigon, U.S. Ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge proposed that the U.S. send a neutral interlocutor to Hanoi to present an ultimatum to North Vietnam to "call off" the Viet Cong. Canadian diplomat J. Blair Seaborn was later selected to undertake the mission after consultations between Canada and the United States.[15]

- 27 April

Operation Quyet Thang 202, an ARVN operation carried out with US support, began. The one-month-long operation claimed heavy damages to the Do Xa sanctuary which linked the Viet Cong's supply lines between Laos and Vietnam's central highlands.

- 30 April

Former President John F. Kennedy's brother, Robert Kennedy, said in an oral interview for the Kennedy Library that President Kennedy had "a strong, overwhelming reason for being in Vietnam and that we should win the war in Vietnam." Kennedy denied that any consideration had been given by the President to withdrawing from Vietnam. He equivocated on the introduction of U.S. ground troops into Vietnam, saying that "we'd face that when we came to it."[16]

May

- 2 May

Viet Cong commandos eluded detection and placed an explosive on the USS Card, an escort aircraft carrier of World War II vintage. The ship, moored in the Saigon River, sunk and 5 American sailors were killed. The USS Card was later raised and repaired.[17]

- 9 May

Former President Diem's brother, Ngo Dinh Can was executed by order of General Khanh. U.S. Ambassador Lodge asked that Can's life be spared, but Khanh chose to placate the militant Buddhist movement in South Vietnam.[18]

- 12 May

American Ambassador Lodge said in a secret meeting that Buddhist leader Thich Tri Quang is "ambitious, anti-Christian, full of hatreds, and agitating against [the government of] Khanh. He said that "some communist infiltration of Buddhists exists."[19]

- 23 May

Western sources estimated the North Vietnamese army (PAVN or NVA) to number 16 divisions totaling 280,000 men, plus militias with 180,000 men, and a border force of 20,000 men. A reserve militia force numbered 400,000. North Vietnam had not yet infiltrated any elements of the PAVN into South Vietnam.[20]

- 24 May

Senator Barry Goldwater, who would become the Republican Party candidate for President of the United States later in 1964, discussed the use of nuclear bombs against North Vietnam to interrupt supply lines for the Viet Cong in South Vietnam. In the face of widespread criticism of his remarks, Goldwater said he was only "repeating a suggestion made by competent military people." Democrats used Goldwater's statements about the use of nuclear weapons to portray him as an extremist in the election campaign.[21]

- 27 May

President Johnson revealed the depth of his uncertainty about South Vietnam in a conversation with Senator Richard Russell. Johnson said his advisers were telling him to "show some power and some force", but he didn't believe the American people were behind the war. Russell agreed. Russell expressed doubt that bombing North Vietnam would win the war. Johnson said he didn't know how to get out of the Vietnam War, adding that he would be impeached if he were to withdraw from the war. "I don't know how in the hell you're gonna get out unless they [the Senate Republicans] tell you to get out."

After the talk with Russell, Johnson telephoned his adviser McGeorge Bundy and said, "I don't think it [South Vietnam] is worth fighting for and I don't think we can get out. It's just the biggest damn mess I ever saw."[22]

June

- 4 June

United Nations Security Council Resolution 189, adopted unanimously, deplored an incident caused by the penetration of military units of South Vietnam into Cambodia and requested compensation for the Cambodians. The resolution also requested that all States and authorities recognize and respect Cambodia's neutrality and territorial integrity, and sent three of its members to the sites of the most recent incidents and to report back to the Council in 45 days with recommendations.[23]

- 6 and 7 June

The Pathet Lao shot down two American reconnaissance planes over Laos. President Johnson authorized an air strike against a Pathet Lao anti-aircraft battery.[24]

- 8 June

Australia's Minister for Defence announced that the Australian Army Training Team Vietnam would be increased to 83 advisers and their role will be expanded.[25]

- 18 June

Canadian diplomat Blair Seaborn met with North Vietnamese prime minister Phạm Văn Đồng to deliver a U.S. message. The U.S., he said, would choose escalation of the conflict rather than withdrawal. The United States considered the Vietnam War to be a confrontation with communism and thus of international importance. Dong responded that any peaceful settlement in South Vietnam had to result in the withdrawal of the United States, the neutralization of South Vietnam, and the eventual reunification of South and North Vietnam. Seaborn's conclusion was that North Vietnam's leaders were "completely convinced that military action at any level is not, repeat not, going to bring success for the US and government forces in South Vietnam." The North Vietnamese emphasized their "quiet determination to go on struggling as long as necessary to achieve objectives which they said they were bound to achieve in the long run."[26]

The New York Times published the remarks of a U.S. military adviser in South Vietnam, later identified as Colonel Wilbur Wilson. Wilson said that the Viet Cong were stronger and better armed than they had been three years earlier and that more than 90 percent of their weapons were of U.S. origin, captured from the South Vietnamese army. Wilson advocated a massive increase in the U.S. military commitment to South Vietnam.[27]

- 20 June

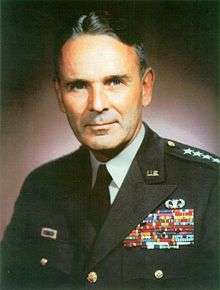

General William Westmoreland replaced General Paul D. Harkins as the commander of the Military Assistance Command Vietnam (MACV)[28] General Maxwell Taylor engineered the appointment of Westmoreland, over the objections of some of his military colleagues.[29] Westmoreland had also been a favorite general of former President John F. Kennedy. "Westy" had little experience with counterinsurgency.[30]

- 29 June

The Republican members of the United States House of Representatives, released a statement saying, "A victory in South Vietnam over the military and subversive threats of Communism is urgently required." Republican Congressman Gerald Ford said that the U.S. should "take command of the forces in Vietnam and not simply remain advisers."[31]

July

- 1 July

General Maxwell Taylor was appointed as the U.S. Ambassador to South Vietnam, replacing Henry Cabot Lodge Jr.

- 6 July

The Battle of Nam Dong was fought when the Viet Cong attacked the Nam Dong Civilian Irregular Defense Group (CIDG) camp in an attempt to overrun it. Warrant Officer Class Two Kevin Conway was killed in action, the first Australian battle casualty of the war.[32]

- 8 July

U Thant, Secretary General of the United Nations said at a press conference that "the only sensible solution" to the war in South Vietnam was to reconvene the Geneva Conference of 1954 to negotiate peace in Southeast Asia. The U.S. rejected his proposal. President Johnson later said, "We do not believe in conferences called to ratify terror."[33]

- 11 July

The New York Times published a petition signed by more than 5,000 American academics urging that the U.S. government work toward the neutralization of South Vietnam. The spokesman for the group Hans J. Morgenthau said that escalation of the war was not the answer.[34]

- 23 July

In a speech in the Senate, Senator Frank Church said he could not understand how "25,000 hardcore Viet Cong" could "thwart the American-backed South Vietnamese government." The Viet Cong were being supplied by men with packs on their back traversing jungle trails, while the U.S. was sending shiploads of equipment and hundreds of millions of dollars to South Vietnam every year. Church also opposed widening the war by bombing North Vietnam. "Expanding the war is not getting out.... It is getting further in." This was Church's first public declaration of concern about the trajectory of the Vietnam War.[35]

- 30 July

Prime Minister Khánh advocated an attack on North Vietnam by the U.S. and South Vietnam. The British Embassy in Saigon reported that if Khánh's demands for an attack were not met, he might resign the premiership or attempt to make a peace agreement with the Viet Cong. The Saigon Daily News said that, without an attack on the North, neutralism for South Vietnam would become a reality.[36]

August

Former Vice President Richard Nixon published an article in the Reader's Digest titled "Needed in Vietnam: The Will to Win." Nixon accused the Johnson administration of compromise, weakness, and inconsistency. He said that the U.S. should use its military power "to win this crucial war—and win it decisively." In public statements Nixon said that the U.S. should "take a tougher line toward Communism in Asia" and expand the war to North Vietnam and Laos.[37]

- 2 August

The first Gulf of Tonkin incident occurred in territorial waters off the coast of North Vietnam. The destroyer USS Maddox, performing a DESOTO patrol, was engaged by three North Vietnamese Navy torpedo boats of the 135th Torpedo Squadron. In the ensuing sea battle, the Maddox expended over 280 3" and 5" shells, and four United States Navy F8 Crusader jet fighter bombers strafed the Vietnamese. There was damage to one US aircraft, one 14.5mm hit on the destroyer, 3 damaged torpedo boats, 4 North Vietnamese sailors killed and 6 wounded, with no US casualties.[38] Although the United States claimed that the Maddox was engaged in peaceful surveillance, on nearby islands South Vietnam forces were conducting Operation 34A guerrilla raids.[39]

- 4 August

U.S. destroyers Maddox and C. Turner Joy reported that they were under fire, in a second Tonkin Gulf incident. Evidence suggests, however, that no actual attack took place.[40] President Johnson informed Congressional leaders that he was ordering retaliatory air strikes on North Vietnam from U.S. aircraft carriers stationed off shore of Vietnam. Among the Congressional leaders, only Senator Mike Mansfield disagreed with the retaliation.[41]

- 5 August

China ordered its military forces near the border with North Vietnam to be in a state of readiness and to "be ready to cope with any possible sudden attack" by the United States.[42]

In retaliation for the Tonkin Gulf Incident, Operation Pierce Arrow consisted of 64 strike sorties of aircraft from the aircraft carriers USS Ticonderoga and USS Constellation against the torpedo boat bases of Hon Gai, Loc Chao, Quảng Khê, and Phuc Loi, and the oil storage depot at Vinh. The U.S. lost two aircraft to anti-aircraft fire, with one pilot killed, Lieutenant Richard Sather. Another, Ensign Everett Alvarez Jr.[43] an A-4 Skyhawk pilot, became the first U.S. Navy prisoner of war in Vietnam.[44]

- 6 August

The British Consul General in Hanoi cabled London that the only "plausible explanation" for the Tonkin Gulf incident "seems to be that it was a deliberate attempt by the Americans to provoke the North Vietnamese into hostile reaction."[45]

China said about the Tonkin Gulf Incident that "Aggression by the United States against the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (North Vietnam) means aggression against China. China will not stand idly by without lending a helping hand."[46] China immediately gave North Vietnam 51 MiG fighter planes, offered training to North Vietnamese pilots, built airports in southern China to serve as sanctuaries for North Vietnamese warplanes, and provided weapons for the Viet Cong.[47]

- 7 August

Prime Minister Khánh declared a state of emergency and suspended the constitution in South Vietnam. This triggered large demonstrations by Buddhists and students in Saigon.[48]

- 10 August

The U.S. Congress voted on the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution authorizing the President "to take all necessary steps, including the use of armed force, to assist any member or protocol state of the Southeast Asia Collective Defense Treaty requesting assistance in defense of its freedom".[49] The unanimous affirmative vote in the House of Representatives was 416–0. The Senate conferred its approval by a vote of 88–2. Some members expressed misgivings about the measure, but in the end, only Democratic Senators Wayne Morse of Oregon and Ernest Gruening of Alaska cast opposing votes.[50]

- 13 August

Chinese leader Mao Zedong told North Vietnamese leader Lê Duẩn that he did not believe that the American provocation in the Tonkin Gulf meant war and that neither the Americans, the North Vietnamese, nor the Chinese wanted war. Therefore, "because no one wants to fight a war, there will be no war."[51]

Robert Thompson, counterinsurgency expert and head of the British Advisory Mission to South Vietnam, wrote to his government in London. "Defeat by the Viet Cong, through subversion and increased guerrilla activity is inevitable, and this prospect will become gradually more apparent over the next few months. The U.S., he said, should seek negotiations with North Vietnam or they "could be forced to insert combat troops in some strength."[52]

- 15 August

After a return visit to North Vietnam, Canadian diplomat J. Blair Seaborn reported to Ottawa and Washington. He offered American terms to North Vietnam's Prime Minister Phạm Văn Đồng: cease support for the Viet Cong and receive financial benefits from the United States; continue support and suffer the consequences. Đồng was furious. He said that the United States carried "the war to the North in order to find a way out of the impasse in the South" and added that "Johnson worries... about the coming electoral battle in which it is necessary to outbid the Republican candidate." Dong expressed support for negotiations in Geneva.[53]

- 21 August

The Viet Cong inflicted more than 150 casualties on an ARVN unit in Kiến Hòa Province. Four American soldiers were killed. General Westmoreland was dismayed because no local South Vietnamese had informed the ARVN that the Viet Cong were setting up the ambush.[54]

- 27 August

With demonstrations against the Khanh government and the U.S. continuing, Buddhist leader Thich Tri Quang told U.S. Embassy officials in Saigon that "the Buddhists could not accept government by Christians" and that the Buddhists might withdraw from the war, "leaving Catholics aided by Americans to fight the Communists."[55]

- 29 August

Faced with large protests, General Khánh abruptly resigned as Prime Minister of South Vietnam on 25 August; returned to power as part of a triumvirate on 27 August; and then fled Saigon to take refuge in Da Lat. In Saigon and other cities, street fighting among Roman Catholics, Buddhists, and students broke out. The National Liberation Front (Viet Cong) applauded the struggle against the "confused puppet government"[56]

- 31 August

U.S. Ambassador Maxwell Taylor journeyed to Dalat and persuaded Khánh to return to Saigon to resume leadership of the government. The CIA analyzed the situation. "War weariness and a desire for a quick solution to the long struggle against the Viet Cong may be an important factor underlying the current agitation.... The confused situation is extremely vulnerable to exploitation by the Communists and by the proponents of a negotiated settlement." Khánh, however, was increasingly coming under the influence of militant Buddhists, led by Thích Trí Quang, who opposed foreign influences such as the United States and Catholicism.[57]

September

- 4 September

Assistant Secretary of Defense John McNaughton recommended to his superior, Robert McNamara, that, given the chaotic state of South Vietnam, the U.S. consider sending a significant number of combat troops to South Vietnam and provoke actions to justify an air war against North Vietnam. Other advisers of President Johnson were making similar proposals.[58]

- 6 September

Ambassador Taylor in Saigon reported to the Department of State in Washington that in South Vietnam only "the emergence of an exceptional leader could improve the situation." He proposed that the U.S. assume "increased responsibility" for the outcome of the Vietnam War because "The consequences of this defeat in the rest of Asia, Africa, and Latin America would be disastrous."[59]

- 10 September

President Johnson approved National Security Action Memorandum 314 which authorized the resumption of naval patrols in the Tonkin Gulf and clandestine operations against North Vietnam under Operation 34A, limited actions in Laos, retaliatory actions if U.S. personnel were attacked, and continued economic aid to South Vietnam.[60]

- 13 September

Prompted by Prime Minister Khánh's concessions to the Buddhists,[61] General Dương Văn Đức attempted a bloodless coup d'état. Air Force Commander Nguyễn Cao Kỳ and Catholic General Nguyễn Văn Thiệu helped Khánh put down the coup.[62]

- 15 September

UN Secretary General U Thant secured agreement from North Vietnam to engage in exploratory talks with the United States. He passed that information to the U.S.'s UN Ambassador Adlai Stevenson who was "favorably surprised" and conveyed the news to Secretary of State Rusk. The U.S. did not respond to U Thant's invitation for talks and Stevenson was later told that President Johnson was too busy with the election to respond. It is unclear whether Thant's invitation for talks was ever shared with Johnson.[63]

- 19 September

A Montagnard revolt broke out in South Vietnam, near the central highland city of Ban Me Thout. U.S. Special Forces soldiers had been training Montagnard soldiers under the CIDG program. The Montagnards launched attacks against South Vietnamese Special Forces soldiers and militiamen, killing several dozen and capturing hundreds. About 2,000 Montagnards faced off against a division of the South Vietnamese army. Several U.S soldiers were taken hostage, while other U.S. Special Forces personnel served as intermediaries between the ARVN and the Montagnards.

- 27 September

The High National Council of South Vietnam, a civilian legislative body, elected Phan Khắc Sửu as its Chairman and Tran Van Huoung as Prime Minister. The job of the council was to draft a new constitution. The U.S. had urged the creation of the council to reduce the visibility of the South Vietnamese military in the government. Prime Minister Huong repressed Buddhist demonstrations in the months ahead.[64]

- 28 September

After negotiations, the last of the Montagnards in revolt released their prisoners. U.S. Special Forces remained with the Montagnards to maintain calm. The South Vietnamese government agreed to meet with the Montagnards to discuss their grievances. A few days later, a Montagnard congress demanded more autonomy for the Montagnards, including a 50,000 man Montagnard army trained by U.S. Special Forces rather than South Vietnamese or the U.S. Military Advisory Assistance Group (MAAG). The Military Assistance Command Vietnam (MACV) was displeased that the Montagnard showed more loyalty to the U.S. Special Forces than to South Vietnam.[65]

October

- 5 October

George Ball, Undersecretary of State, wrote a lengthy memo dissenting from the direction of U.S. policy on Vietnam. He said the U.S. should tell South Vietnamese leaders the U.S. will continue support "only if they achieve a unity of purpose... and create a government free from factionalism and capable of carrying on the affairs of the country." He continued, "We have spent months of concentrated effort trying to devise ways and means to advance the present policy of winning the war.... But we have given almost no attention to the possible political means of finding a way out without further enlargement of the war." The memo was read and responded to by Johnson's top advisers on Vietnam—but apparently was never shown to the President.[66]

- 8 October

In the midst of a Presidential campaign, The New York Times excoriated Republican candidate Barry Goldwater for wanting "to convert an Asian war into an American war" in South Vietnam. Goldwater had accused President Johnson of being indecisive and insufficiently aggressive in combating the spread of communism.[67]

- 11 October

The North Vietnamese Central Military Commission ordered the Viet Cong and the North Vietnamese Army to jointly "annihilate a part of the enemy's main force units" in South Vietnam between December 1964 and March 1965. Prior to this announcement, units of the North Vietnamese Army had not participated in the war in South Vietnam.[68]

- 15 October

Nguyễn Văn Trỗi was executed by firing squad in South Vietnam. A Vietnamese electrical worker and Viet Cong urban guerrilla, he was captured after trying to assassinate Secretary of Defense McNamara and future ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr. who were visiting South Vietnam, in May 1963. Troi was the first publicly executed Viet Cong.[69]

- 16 October

The People's Republic of China conducted its first successful nuclear weapons test. China's possession of nuclear weapons was seen in both Peking and Hanoi as a deterrent to an American invasion of North Vietnam.[70]

- 24 October

Pham Khac Suu was appointed to the largely ceremonial position of Head of State of South Vietnam by the High National Council. The next day, U.S. Ambassador Maxwell Taylor met with Suu and expressed his displeasure that the action had been taken without consulting with the United States. Taylor said that, in the future, "We could not accept" a failure of the government to consult with the U.S.[71]

- 27 October

Head of State Suu appointed Trần Văn Hương as Prime Minister of South Vietnam. Buddhists launched demonstrations against the Hương government. Hương was more resistant to Buddhist demands than the previous Prime Minister, General Khánh, had been. Khánh, however, remained important among the generals [72]

November

- 1 November

The Viet Cong attacked the Bien Hoa Air Base, 15 miles north of Saigon, with mortars. Four Americans and two Vietnamese were killed and 27 American aircraft were destroyed or damaged. U.S. Ambassador Taylor reported that the Viet Cong "had changed the ground rules" by targeting a U.S. installation. He advocated a reprisal.[73]

- 3 November

President Lyndon Johnson won a landslide victory over his Republican opponent, Barry Goldwater, in the Presidential election. Johnson was perceived as the more moderate candidate on issues including the use of U.S. military forces in Vietnam.

- 10 November

From Saigon, Ambassador Maxwell Taylor cabled Washington with his views. Perhaps former President Kennedy's most influential adviser on Vietnam, Taylor favored the U.S. expanding its participation in the war against the Viet Cong and expanding the war to North Vietnam, even if the government of South Vietnam never became competent—advocating the removal of a previous U.S. prerequisite for participation in the war: the existence of a stable and efficient South Vietnamese government.[74]

- 19 November

A Vietnam working group of mid-level officials from the Departments of State and Defense and the CIA presented its analysis to the senior policymakers of the Johnson Administration. The working group identified three U.S. policy options: Option A was to continue the present policy and reject negotiations with North Vietnam until the situation in South Vietnam improved; Option B was much increased military pressure against North Vietnam until the insurgency in the South was defeated; Option C called for a continuation of present policy but with gradually increased military pressure against the North with no firm position for or against negotiations. Option C was favored by the policymakers.[75]

- 20 November

Three regiments (the first full units) of the North Vietnamese Army to be sent to South Vietnam, to assist the Viet Cong, departed from North Vietnam to march south along the Ho Chi Minh Trail. (Other NVA troops may have left North Vietnam in October.)[76]

- 28 November

U.S. Army Capt. Norman W. Heck, in his last letter home before being killed, said that winning the war would be difficult, but that "A fairly effective program of improving the economic and political situation [of South Vietnam] is... the whole key to success in winning the whole hearted support of the people, and not in the number of Viet Cong killed."[77]

December

- 6 December

The Battle of An Lao began when the Viet Cong and units of the North Vietnamese army captured the district headquarters of An Lao, Bình Định, about 300 miles from Saigon. The communist forces were successful in repeatedly beating back large numbers of counterattacking ARVN troops. This battle was the first time in that area the communists "used the new tactic of coordinating main force units with local and guerrilla forces."[68]

- 14 December

Operation Barrel Roll began, a covert interdiction and close air support campaign by the U.S. Air Force 2nd Air Division (later the Seventh Air Force) and U.S. Navy Task Force 77, conducted in the Kingdom of Laos. The campaign would continue until 1973.

- 16 December

The U.S. Embassy in Saigon reported that Prime Minister Huoung had successfully repressed Buddhist demonstrations against the government, had imposed censorship and shut down ten newspapers suspected of collaborating with communists.[78]

- 19 December

A Cambodian diplomat in Hanoi reported that "Anti-aircraft guns have been positioned on rooftops, and people are busy digging trenches in the streets." Author Pierre Asselin later said, "Although Americans did not know it at the time, the Vietnam War had begun."[79]

- 20 December

In South Vietnam, former Prime Minister General Khánh led a group of military officers called the "Young Turks" in a coup. They dissolved the civilian High National Council, arrested a number of military officers and civilian officials, and created an Armed Forces Council. Hương remained as Prime Minister. U.S. Ambassador Taylor was outraged by the coup, berating Khánh and the Young Turks who, he said, had acted "without consulting with U.S. representatives and in disregarding our advice on important matters."[80]

- 22 December

In a press conference, General Khánh said, "it was better to live poor but proud as free citizens of an independent country rather than in ease and shame as slaves of the foreigners and Communists." Khánh told an American journalist that if Ambassador Taylor "did not act more intelligently, Southeast Asia would be lost."[81]

- 24 December

The Brinks Hotel in Saigon was bombed by the Viet Cong. Two Viet Cong operatives detonated a car bomb underneath the hotel, which housed United States Army officers; the explosion killed two American officers and injured approximately 60, including military personnel and Vietnamese civilians. So unsettled was the situation in South Vietnam that the U.S. could not immediately determine whether the attack was by the Viet Cong or by disenchanted South Vietnamese officials.[82]

- 29 December

The Guardian echoed a large number of media outlets worldwide, saying, "Perhaps the least damaging decision for America... would be a withdrawal (from South Vietnam) based on a clear and detailed statement explaining the impossibility of assisting a sovereign country to defend itself when it refuses to concentrate its own efforts or its own defense, or to abandon its internal factional struggles."[83]

- 28 December – 2 January 1965

In the Battle of Binh Gia, a Catholic village not far from Saigon was attacked by the Viet Cong. Before retiring, the Viet Cong killed 201 ARVN soldiers and five American advisers. Binh Ghia was the largest battle that had taken place between the ARVN and the Viet Cong.[84]

- 30 December

President Johnson cabled Ambassador Taylor in Saigon, criticizing Taylor for his inability to communicate "sensitively and persuasively" with the South Vietnamese during the ongoing political crisis there. Turning to the military situation, Johnson said, "Every time I get a military recommendation it seems to me that it calls for large-scale bombing. I have never felt that this war will be won from the air, and it seems to me that what is much more needed and would be more effective is a larger and stronger use of Rangers and Special Forces and Marines, or other appropriate military strength on the ground." Johnson said, "I myself am ready to substantially increase the number of Americans fighting in Vietnam."[85]

- 31 December

Two hundred and sixteen American soldiers were killed in the Vietnam War in 1964.[86] 23,310 U.S. military personnel were in South Vietnam at the end of the year.[87] The South Vietnamese armed forces suffered 7,457 killed in action, about 30 percent more than the total killed in the previous year.[88]

Over the course of the year, in South Vietnam the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese main-force soldiers increased from an estimated 23,000 to 33,000, while the total number of both regular and guerrilla armed communist personnel was about 100,000. They were better armed, especially with Chinese-made AK-47s, and more aggressive. Casualties inflicted on South Vietnam's armed forces increased from 1,900 in January to 3,000 in December.[89] An estimated 12,400 soldiers from North Vietnam were infiltrated into South Vietnam during the year.[90]

Year in numbers

| Armed Force | Strength | KIA | Reference | Military costs – 1964 | Military costs – 2014 | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 514,000 | 7,457 | [91] | |||||

| 23,310 | 216 | [91][92] | |||||

| 200 | [91] | ||||||

| 200 | [91] | ||||||

| 20 | [91] | ||||||

| 30 | [91] | ||||||

| 100,000 [93] |

Notes

- Lewy, Gunther (1978), America in Vietnam, New York: Oxford University Press, p. 24, 455.

- Center of Military History 2004, p. 582

- Clarke, p. 275

- Logevall, p. 93

- Logevall, pp. 92–93

- Asselin, pp. 164–169

- Asselin, pp. 170–173

- Logevall, p. 103

- Mann, p. 311

- Logevall, p. 113

- Kaiser, pp. 304–305

- Mann, p. 318

- Mann, pp. 323–324

- Johns, Andrew L. (jun 199), "A Voice from the Wilderness: Richard Nixon and the Vietnam War, 1964–1966", Presidential Studies Quarterly, Vol. 29, No. 2, p. 318.

- Logevall, pp. 155–156

- "Was Kennedy Planning to Pull Out of Vietnam", http://mcadams.posc.mu.edu/vietnam.htm, accessed 18 Sep 2014

- "Lost Battles of the Vietnam War", http://www.g2mil.com/lost_vietnam.htm, accessed 21 Aug 2015

- Moyar, Michael (Oct 2004), "Political Monks: The Militant Buddhist Movement during the Vietnam War," Modern Asian Studies, Vol 28, No. 4, p. 755. Downloaded from JSTOR.

- Moyar, p. 756

- Asselin, pp. 175, 179–181, 275

- "Goldwater suggests using atomic weapons"; http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/goldwater-suggests-using-atomic-weapons Archived 2015-03-30 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 18 Sep 2014

- Mann, pp. 328–330

- Wellens, p. 320

- Mann, p. 314

- Hartley 2002, p. 242.

- Logevall, pp. 162–163

- Logevall, pp. 166–167, 463–464

- Logevall, p. 164

- McMaster, p. 111

- Buzzanco, p. 167

- Mann, p. 340

- "Vietnam – Australia's Longest War: A Calendar of Military and Political Events". Vietnam Veterans Association of Australia. 2006. Retrieved 2006-07-01.

- Logevall, pp. 185–189

- Logevall, p. 167

- Mann, pp. 337–339

- Logevall, p. 192

- "A Voice from the Wilderness: Richard Nixon and the Vietnam War, 1964–1966", http://www.thefreelibrary.com/A+Voice+from+the+Wilderness%3a+Richard+Nixon+and+the+Vietnam+War%2c...-a054859917, accessed 18 Sep 2014

- Moïse 1996, pp. 78, 82, 92

- Logevall, p. 197

- Moïse 1996, pp. 106–107

- Logevall, pp. 198–199

- Chen Jian (June 1995), "China's Involvement in the Vietnam War, 1964–69", The China Quarterly, No. 142, p. 364

- Interview with Everett Alvarez, 1981

- Michael Clodfelter, Vietnam in Military Statistics: A History of the Indochina Wars, 1792–1991 (Jefferson, North Carolina & London: McFarland & Company, Inc., 1995), p. 56.

- Logevall, p. 292

- Logevall, pp. 207–208

- Asselin, p. 201; Logevall, pp. 207

- Mann, p. 371

- H.J. RES 1145 1964

- Logevall, pp. 203–204

- Logevall, p. 208

- Logevall, pp. 222–223

- Logevall, pp. 208–209

- Logevall, p. 219

- Moyar, p. 758

- Logevall, pp. 218–219

- Logevall, pp. 220–221, 240–241

- Logevall, p. 231

- Young, p. 126

- Buzzanco, p. 172

- Moyar, p. 764

- Kaiser, p. 345

- Logevall, p. 212

- McMaster, p. 165; Moyar, p. 767

- Stanton, pp. 79–83

- Logevall, pp. 243–248

- Logevall, p. 238

- Asselin, p. 204

- Reuters (15 October 1964). "Saigon Executes Youth For Plot on McNamara". The New York Times

- Asselin, 201

- FRUS, document 387, http://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1964-68v01/d387, accessed 20 Sep 2014

- Moyar, pp. 766–767

- Mann, pp. 378–379

- Logevall, p. 261

- Logevall, pp. 258–2259

- Asselin, p. 200

- Gilbert, Marc Jason, "The Cost of Losing the 'Other War' in Vietnam" (2002), in Why the North Won the Vietnam War ed by Marc Jason Gilbert, New York: Palgrave p. 160

- Moyar, p. 767

- Asselin, p. 205

- Logevall, pp. 292–293

- Moyar, p. 771

- Logevall, p. 293

- Logevall, p. 294

- Kreepinevich, Jr., p. 134

- FRUS, Document 297; Logevall, p. 299

- "Statistical Information about Fatal Casualties of the Vietnam War" https://www.archives.gov/research/military/vietnam-war/casualty-statistics.html, accessed 8 Sep 2014

- "Timeline, 1963–1964, http://www.vietnamgear.com/war1963.aspx, accessed 8 Sep 2014

- Clarke, Jeffrey J. (1988), United States Army in Vietnam: Advice and Support: The Final Years, 1965–1973, Washington, DC: Center of Military History, United States Army, p. 275

- Garland, John (2000), United States Army in Vietnam: Combat Operations: Stemming the Tide, May 1965 to October 1966, Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History, United States Army, p. 12

- Lewy, Guenther (1978), America in Vietnam, New York: Oxford University Press, p. 66

-

War Remnants Museum Data

Armed Force 1964 1965 1966 1967 1968 1969 1970 1971 1972

514,000 643,000 735,900 798,800 820,000 897,000 968,000 1,046,250 1,048,00053**553(55((3(5(5minute ththhthntththte digest my nuts

23,310 180,000 385,300 485,600 549,500 549,500 335,790 158,120 24,000

200 20,620 25,570 47,830 50,000 48,870 48,540 45,700 36,790 .svg.png)

200 1560 4530 6820 7660 7670 6800 2000 130

0 20 240 2220 6000 11,570 11,570 6000 40

20 70 2060 2020 1580 190 70 50 50

30 120 160 530 520 550 440 100 50 - United States 2010

- Center of Military History p. 582. 100,000 is the estimated number of the insurgent force in South Vietnam.

References

- Asselin, Pierre (2013), Hanoi's Road to the Vietnam War, 1954–1965 Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013. ISBN 978-0-520-27612-3

- Buzzanco, Robert (1996), Masters of War: Military Dissent and Politics in the Vietnam Era, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-48046-9.

- Center of Military History (2004). American Military History (2004 ed.). Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 1-4191-0001-7. Retrieved 1 April 2010.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Total pages: 704

- Clarke, Jeffrey J. (1988), United States Army in Vietnam: Advice and Support: The Final Years, 1965–1973, Washington, DC: Center of Military History, United States Army.

- Foreign Relations of the United States, 1964–1968, Volume I, Vietnam, 1964. U.S. Department of State.

- Garland, John (2000), United States Army in Vietnam: Combat Operations: Stemming the Tide, May 1965 to October 1966, Washington, DC.: Center of Military History, United States Army.

- Kaiser, David (2000), American Tragedy: Kennedy, Johnson, and the Origins of the Vietnam War Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-00225-3.

- Krepinevich, Jr. Andrew F. The Army and Vietnam Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-2863-5.

- Lewy, Gunther (1978), America in Vietnam, New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-502391-9.

- Logevall, Frederik (1999), Choosing War: The Lost Chance for Peace and the Escalation of War in Vietnam Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0520229193.

- McMaster, H. R. (1997), Dereliction of Duty, New York: Harper Perennial. ISBN 0-06-018795-6.

- Mann, Robert (2001), A Grand Delusion: America's Descent into Vietnam, New York: Basic Books. ISBN 0-465-04369-0

- Moïse, Edwin E. (1996). Tonkin Gulf and the escalation of the Vietnam War (1996 ed.). UNC Press. ISBN 0-8078-2300-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) 304 pp

- Moyar, Mark (2004), "Political Monks: The Militant Buddhist Movement during the Vietnam War", Modern Asian Studies, Vol. 38, No. 4, pp. 749–784. Downloaded from JSTOR.

- United States, Government (2010). "Statistical information about casualties of the Vietnam War". National Archives and Records Administration. Archived from the original on 26 January 2010. Retrieved March 6, 2010.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stanton, Shelby L. (1985), Green Berets at War: U.S. Army Special Forces in Southeast Asia 1956–1975 Novato, California: Presidio Press. ISBN 0-89141-238-7.

- Wellens, Karen; T.M.C. Asser Instituut (1990). Resolutions and statements of the United Nations Security Council (1946-1989): a thematic guide. Brill. p. 320. ISBN 978-0-7923-0796-9.

- Young, Marilyn B. (1991), The Vietnam Wars: 1945–1990 New York: Harper, Collins Publishers. ISBN 0-06-016553-7.

- "Transcript of Tonkin Gulf Resolution (1964)". Our Documents.