1885 hangings at Battleford

The hangings at Battleford refers to the execution on November 27, 1885 of eight Indigenous men for their role in the North-West Rebellion. They are similar to the largest mass execution in the United States, following the Dakota War of 1862. The executions followed the Frog Lake Massacre, the North-West Resistance, and the Looting of Battleford. Prior to the North-West Resistance the Canadian Government's actions in what would become Saskatchewan resulted in starvation, disease, and death among the Indigenous peoples of the area. Traditional means of self-support, such as buffalo disappeared with the sale of lands.

At both Frog Lake and Battleford, some people took up arms against the wishes of their leaders. Some faced trial and jail or sentence of death. Others fled to the United States.

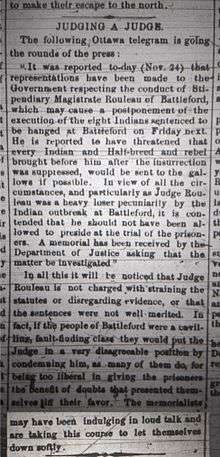

Trial and charges of bias against Stipendiary Magistrate (Judge) Charles Rouleau

The Frog Lake Massacre saw Indian Agent Thomas Trueman Quinn initially shot in the head. Quinn was a notoriously harsh Indian Agent, who kept Indigenous people near Frog Lake on the brink of starvation ("no work, no rations").[1] Quinn treated the Cree with harshness and arrogance.(citation to Sask Encyclopedia)[1] Before dawn on April 2, 1885, a party of Cree warriors captured Quinn at his home. He refused to go to another location with the Cree warriors and was shot dead onsite. In the moments of panic following Quinn's shooting, eight other settler prisoners were shot dead.

Following the resistance at Frog Lake, the participants were taken to Battleford. Wandering Spirit pleaded guilty and was sentenced to hang on September 22, 1885.

The major trial condemning six of the eight men to death by hanging was heard by Battleford "Resident Stipendiary Magistrate" (Judge) Charles Rouleau. He was described as a "heavy loser pecuniarily" after the Looting of Battleford in the December issue of the Saskatchewan Herald following the hangings - in reality, his house had been burned to the ground, and he reportedly threatened that

"every Indian and Half-breed and rebel brought before him after the insurrection was suppressed, would be sent to the gallows if possible."[2]

The Cree-speaking men who were sentenced to hang were not provided with translation at their trial.

People sentenced to death at Battleford

The following people were sentenced to die in Battleford. The first six names relate to murders which occurred at the Frog Lake Massacre, while the final two relate to murders which occurred during Looting of Battleford.

- Kah - Paypamahchukways (Wandering Spirit) for the murder of T. T. Quinn, Indian Agent.

- Pah Pah-Me-Kee-Sick (Walking the Sky) for the murder of Léon Fafard O.M.I., a Roman Catholic priest.

- Manchoose ( Bad Arrow) for the murder of Charles Govin, Quinn's interpreter.

- Kit-Ahwah-Ke-Ni (Miserable Man) for the murder of Govin.

- Nahpase (Iron Body) for the murder of George Dill, Free Trader.

- A-Pis-Chas-Koos (Little Bear) for the murder of Dill.

- Itka (Crooked Leg) for the murder of Payne, Farm Instructor of the Stoney Reserve south of Battleford.

- Waywahnitch (Man Without Blood) for the murder of Tremont, Rancher out of Battleford.

The hangings

There are a number of first-hand historical records that exist of the Hangings at Battleford, however the majority of accounts are written from the perspective of settlers in the area. Blood Red the Sun, a work by William Bleasdell Cameron, first published in 1926 as The War Trail of Big Bear, describes the events leading up to the Frog Lake Massacre and the executions in significant detail - albeit from the perspective of someone whose friends and colleagues were killed at the Frog Lake Massacre. Cameron was an HBC employee whose life was spared by Wandering Spirit.[1] Cameron testified at the trials against the accused men.

Presence of children from Battleford Residential School

A number of sources indicate that children from Battleford Industrial School were brought from the school to witness the hangings as a "warning".

Historical significance

The hangings at Battleford are an example of British colonialism and subjugation of Indigenous peoples in what would become the Canadian prairie provinces two decades later. In his seminal 1970s-era histographical account of Indian policy in Canada, Prisons of Grass, Howard Adams points to the significance of the hangings at Battleford:

"Every member of the Indian nation heard the death-rattle of the eight heroes who died at the end of the colonizers rope and they went quietly back to their compounds, obediently submitting themselves to the oppressors. The eight men who sacrificed their lives at the end of the rope were the champions of freedom and democracy. They were incomparable heroes, as shown by their last moments."[3]

Rediscovery of the gravesite

After the hangings, the bodies were placed in a mass grave near the fort. It remained hidden for many years. In 1972, the gravesite was rediscovered by students who followed old plans of the fort in order to find the burial location.(citation to sask Indian article). The location was marked with a cement pad and chain fence. In later years, this was removed and replaced with a modern headstone bearing the names of the executed men. There is also an interpretive panel explaining the history of the burial site.

The gravesite is located on public property in the Town of Battleford at 52.73175°N 108.294886°W near the Eiling Kramer Campground and Fort Battleford.

References

- "Biography – KAPAPAMAHCHAKWEW – Volume XI (1881-1890) – Dictionary of Canadian Biography". Retrieved 2017-05-24.

- Laurie, Patrick Gammie (14 December 1885). "Judging a Judge".

- Adams, Howard (1975). Prison of Grass. Saskatoon: Fifth House Publishers. pp. 97. ISBN 0-920079-51-2.