Zuni

Zuni girl with jar, 1903 | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 19,228 enrolled members (2015) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| United States (New Mexico) | |

| Languages | |

| Zuni, English | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Pueblo people |

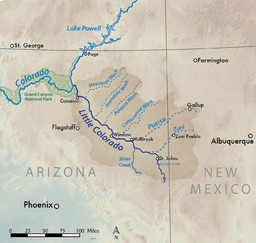

The Zuni (Zuni: A:shiwi; formerly spelled Zuñi) are Native American Pueblo peoples native to the Zuni River valley. The current day Zuni are a Federally recognized tribe and most live in the Pueblo of Zuni on the Zuni River, a tributary of the Little Colorado River, in western New Mexico, United States. The Pueblo of Zuni is 55 km (34 mi) south of Gallup, New Mexico. In addition to the reservation, the tribe owns trust lands in Catron County, New Mexico, and Apache County, Arizona.[1] The Zuni call their homeland Halona Idiwan’a or Middle Place.[2]

History

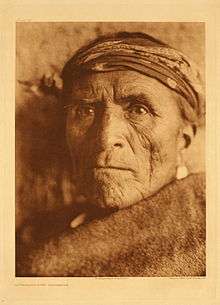

_(cropped).jpg)

Archaeology suggests that the Zuni have been farmers in their present location for 3,000 to 4,000 years. It is now thought that the Zuni people have inhabited the Zuni River valley since the last millennium B.C., at which time they began using irrigation techniques which allowed for farming maize on at least household-sized plots.[4][5]

More recently, Zuni culture may have been related to both the Mogollon and Ancestral Pueblo peoples cultures, who lived in the deserts of New Mexico, Arizona, Utah, and southern Colorado for over two millennia. The "village of the great kiva" near the contemporary Zuni Pueblo was built in the 11th century AD. The Zuni region, however, was probably only sparsely populated by small agricultural settlements until the 12th century when the population and the size of the settlements began to increase. In the 14th century, the Zuni inhabited a dozen pueblos between 180 and 1,400 rooms in size. All of these pueblos, except Zuni, were abandoned by 1400, and over the next 200 years, nine large new pueblos were constructed. These were the "seven cities of Cibola" sought by early Spanish explorers.[6] By 1650, there were only six Zuni villages.[7]

In 1539, Moorish slave Estevanico led an advance party of Fray Marcos de Niza's Spanish expedition. The Zuni reportedly killed Estevanico as a spy.[7] This was Spain's first contact with any of the Pueblo peoples.[8] Francisco Vásquez de Coronado traveled through Zuni Pueblo. The Spaniards built a mission at Hawikuh in 1629. The Zunis tried to expel the missionaries in 1632, but the Spanish built another mission in Halona in 1643.[7]

Before the Pueblo Revolt of 1680, the Zuni lived in six different villages. After the revolt, until 1692, they took refuge in a defensible position atop Dowa Yalanne, a steep mesa 5 km (3.1 miles) southeast of the present Pueblo of Zuni; Dowa means "corn", and yalanne means "mountain". After the establishment of peace and the return of the Spanish, the Zuni relocated to their present location, returning to the mesa top only briefly in 1703.[9]

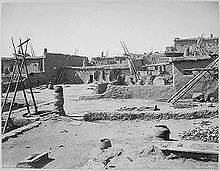

.jpg)

The Zunis were self-sufficient during the mid-19th century, but faced raiding by the Apaches, Navajos, and Plains Indians. Their reservation was officially recognized by the United States federal government in 1877.

Frank Hamilton Cushing, an anthropologist associated with the Smithsonian Institution, lived with the Zuni from 1879 to 1884. He was one of the first non-Indian participant-observers and ethnologists at Zuni. In 1979, however, it was reported that some members of the Pueblo consider he had wrongfully documented the Zuni way of life, exploiting them by photographing and revealing sacred traditions and ceremonies.[10]

A controversy during the early 2000s was associated with Zuni opposition to the development of a coal mine near the Zuni Salt Lake, a site considered sacred by the Zuni and under Zuni control.[11] The mine would have extracted water from the aquifer below the lake and would also have involved construction between the lake and the Zuni. The plan was abandoned in 2003 after several lawsuits.[12]

Culture

_(Native_American)._Kachina_Doll_(Paiyatemu)%2C_late_19th_century.jpg)

The Zuni traditionally speak the Zuni language, a language isolate that has no known relationship to any other Native American language. Linguists believe that the Zuni have maintained the integrity of their language for at least 7,000 years. The Zuni do, however, share a number of words from Keresan, Hopi, and Pima pertaining to religion and religious observances.[13] The Zuni continue to practice their traditional religion with its regular ceremonies and dances, and an independent and unique belief system.

The Zuni were and are a traditional people who live by irrigated agriculture and raising livestock. Gradually the Zuni farmed less and turned to sheep and cattle herding as a means of economic development. Their success as a desert agri-economy is due to careful management and conservation of resources, as well as a complex system of community support. Many contemporary Zuni also rely on the sale of traditional arts and crafts. Some Zuni still live in the old-style Pueblos, while others live in modern houses. Their location is relatively isolated, but they welcome respectful tourists.

The Zuni Tribal Fair and rodeo is held the third weekend in August. The Zuni also participate in the Gallup Inter-Tribal Ceremonial, usually held in early or mid-August. The A:shiwi A:wan Museum and Heritage Center is a tribal museum that showcases Zuni history, culture, and arts.

Zuni ethnobotany

The Zuni utilize many local plants in their culture. For an extensive list, see main article Zuni ethnobotany.

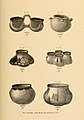

Zuni pottery

Traditionally, Zuni women made pottery for food and water storage. They used symbols of their clans for designs. Clay for the pottery is sourced locally. Prior to its extraction, the women give thanks to the Earth Mother (Awidelin Tsitda) according to ritual. The clay is ground, and then sifted and mixed with water. After the clay is rolled into a coil and shaped into a vessel or other design, it will be scraped smooth with a scraper. A thin layer of finer clay, called slip, is applied to the surface for extra smoothness and color. The vessel is polished with a stone after it dries. It is painted with home-made organic dyes, using a traditional yucca brush. The intended function of the pottery dictates its shape and images painted on its surface. To fire the pottery, the Zuni used animal dung in traditional kilns. Today Zuni potters might use electric kilns. While the firing of the pottery was usually a community enterprise, silence or communication in low voices was considered essential in order to maintain the original "voice" of the "being" of the clay, and the purpose of the end product.[14][15] Sales of pottery and traditional arts provide a major source of income for many Zuni people today. An artisan may be the sole financial support for her immediate family as well as others. Many women make pottery or, less frequently, clothing or baskets.

Carving and silversmithing

Zuni also make fetishes and necklaces for the purpose of rituals and trade, and more recently for sale to collectors.

The Zuni are known for their fine lapidary work. Zuni jewelers set hand-cut turquoise and other stones in silver.[16] Today jewelry-making thrives as an art form among the Zuni. Many Zuni have become master stone-cutters. Techniques used include mosaic and channel inlay to create intricate designs and unique patterns.

Two specialities of Zuni jewelers are needlepoint and petit point. In making needlepoint, small, slightly oval-shaped stones with pointed ends are set in silver bezels, close to one another and side by side to create a pattern. The technique is normally used with turquoise, sometimes with coral and occasionally with other stones in creating necklaces, bracelets, earrings and rings. Petit point is made in the same fashion as needlepoint, except that one end of each stone is pointed, and the other end is rounded.

Religion

Religion is central to Zuni life. Their traditional religious beliefs are centered on the three most powerful of their deities: Earth Mother, Sun Father, and Moonlight-Giving Mother. Revered holy people include Old Lady Salt and White Shell Woman. The Zunis' religion is katsina-based, and most ceremonies occur during the growing season.

Gallery

Zuni vases

Zuni vases.jpg) Zuni pottery (2)

Zuni pottery (2) Zuni paint and condiment cups

Zuni paint and condiment cups Zuni ladles of clay

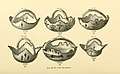

Zuni ladles of clay Zuni bird effigies

Zuni bird effigies Clay baskets of the Zuni

Clay baskets of the Zuni Animal effigies of the Zuni

Animal effigies of the Zuni Zuni sashes

Zuni sashes

See also

Notes

- ↑ "Welcome", Pueblo of Zuni, (retrieved 13 Feb 2011)

- ↑ "Experience Zuni". www.zunitourism.com. Retrieved 2017-11-08.

- ↑ Byrd H. Granger (1960). Arizona Place Names. University of Arizona Press. p. 21. Retrieved 9 December 2011.

- ↑ Zuni Origins: Toward a New Synthesis of Southwestern Archaeology, The University of Arizona Press (30 Dec. 2009), ISBN 978-0816528936, edited by David A. Gregory and David R. Wilcox, pg. 119

- ↑ Damp, Jonathan E. (2008). "The Economic Origins of Zuni" (PDF). Archaeology Southwest. 22 (2): 8. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 June 2014. ; see also Damp, Jonathan E. (2010). "Zuni emergent agriculture: economic strategies and the origins of Zuni". In Gregory, David A.; Wilcox, David R. Zuni Origins: Toward a new synthesis of Southwestern archaeology. Tucson, Arizona: University of Arizona Press. pp. 118&ndash, 132. ISBN 978-0-8165-2893-6.

- ↑ Kintigh, Keith (2008). "Zuni Settlement Patterns: A.D. 950-1680" (PDF). Archaeology Southwest. 22 (2): 15–16. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 June 2014. ; see also Kintigh, Keith (2010). "Late prehistoric and late prehistoric settlement systems in the Zuni area". In Gregory, David A.; Wilcox, David R. Zuni Origins: Toward a new synthesis of Southwestern archaeology. Tucson, Arizona: University of Arizona Press. pp. 361&ndash, 376. ISBN 978-0-8165-2893-6.

- 1 2 3 Pritzker 109

- ↑ David Roberts, The Pueblo Revolt, 56 (Simon and Schuster, 2004). ASIN B000MC1CHQ. Reprint, 2005, ISBN 0-7432-5517-8

- ↑ Flint, Richard and Shirley Cushing Flint "Dowa Yalanne, or Corn Mountain." Archived 2012-07-14 at Archive.is New Mexico Office of the State Historian. 21 April 2012.

- ↑ Frank Hamilton Cushing, Zuni (University of Nebraska, 1979).

- ↑ Neary, Ben. "Mining Plan Pits Tribe Against Power Industry", Los Angeles Times, 2001-02-18. Retrieved on 2009-05-26.

- ↑ Neary, Ben. "Utility Drops Plans for Coal Mine", Santa Fe New Mexican, 2003-08-05. Retrieved on 2009-05-26.

- ↑ Hill, Jane H. "Zunian as a Language Isolate." American Southwest Vol. 22, No. 2, Spring 2008, p. 3

- ↑ Morrell, Virginia. "The Zuni Way ." Smithsonian Magazine. April 2007 (retrieved 13 Feb 2011)

- ↑ Jesse Green, ed. Zuni: Selected Writings of Frank Hamilton Cushing. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1979. ISBN 0-8032-7007-0

- ↑ Adair 14

References

- Adair, John. The Navajo and Pueblo Silversmiths. Norman: University Oklahoma Press, 1989. ISBN 978-0-8061-2215-1.

- Cushing, Frank Hamilton. Jesse Green, ed. Zuni: Selected Writings of Frank Hamilton Cushing. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1978. ISBN 0-8032-2100-2.

- Wade, Edwin L. "The Ethnic Art Market in the American Southwest, 1880-1980." George, W. Stocking, Jr., ed. Objects and Others: Essays on Museums and Material Culture (History of Anthropology). Vol. 3. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1988. ISBN 0-299-10324-2.

- Pritzker, Barry M. A Native American Encyclopedia: History, Culture, and Peoples. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0-19-513877-1.

Further reading

- Benedict, Ruth. Zuni Mythology. 2 vols. Columbia University Contributions to Anthropology, no. 21. New York: Columbia University Press, 1935. AMS Press reprint, 1969.

- Bunzel, Ruth L. "Introduction to Zuni Ceremonialism". (1932a); "Zuni Origin Myths". (1932b); "Zuni Ritual Poetry". (1932c). In Forty-Seventh Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology. Pp. 467–835. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1932. Reprint, Zuni Ceremonialism: Three Studies. Introduction by Nancy Pareto. University of New Mexico Press, 1992.

- Bunzel, Ruth L. Zuni Texts. Publications of the American Ethnological Society, 15. New York: G.E. Steckert & Co., 1933

- Cushing, Frank Hamilton, Barton Wright, The Mythic World of the Zuni, University of New Mexico Press, 1992, hardcover, ISBN 0-8263-1036-2

- Davis, Nancy Yaw. (2000). The Zuni enigma. Norton. ISBN 0-393-04788-1

- Eggan, Fred and T.N. Pandey. "Zuni History, 1855–1970". Handbook of North American Indians, Southwest. Vol.9. Ed. By Alfonso Ortiz. Pp. 474–481. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1979.

- Hart, E. Richard, 2000. "Zuni Claims: An Expert Witness’ Reflections," American Indian Culture and Research Journal, 24(1): 163–171.

- Hart, E. Richard, ed. Zuni and the Courts: A Struggle for Sovereign Land Rights. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1995. ISBN 978-0-7006-0705-1.

- Kroeber, Alfred L. (1984). Zuni kin and clan. AMS Press. ISBN 0-404-15618-5

- Newman, Stanley S. Zuni Dictionary. Indiana University Research Center, Publication Six. Bloomington: Indiana University, 1967. ASIN B0007F3L0Y.

- Roberts, John. "The Zuni". In Variations in Value Orientations. Ed. by F.R. Kluckhorn and F.L. Strodbeck. Pp. 285–316. Evanston, IL and Elmsford, NY: Row, Peterson, 1961.

- Smith, Watson and John Roberts. Zuni Law: A Field of Values. Papers of the Peabody Museum of the American Archaeology and Ethnology, Vol. 43. Cambridge, MA: Peabody Museum, 1954.

- Tedlock, Barbara. The Beautiful and the Dangerous: Dialogues with the Zuni Indians, New York: Penguin Books, 1992.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Zuni. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Pueblo of Zuni official website

- A:shiwi A:wan Museum and Heritage Center at Zuni

- Pueblo of Zuni official Artist’s Art Walk website

- The Zuni Worldview

- Zuni Indian Tribe History, Access Genealogy

- The Religious Life of the Zuñi Child by (Mrs.) Tilly E. (Matilda Coxe Evans) Stevenson, from Project Gutenberg

- Collection of Historical Photographs of Zunis

- Quand les Katchinas dansent a Cibola. Mythologie et rites des indiens Zunis, 15 July 2008

- Zuni Breadstuff by Frank Hamilton Cushing, from Michigan State University Libraries - The Historic American Cookbook Project