Chernobyl Exclusion Zone

| Chernobyl Exclusion Zone (Зона відчуження Чорнобильської АЕС (in Ukrainian)) | |

| Zone of Alienation, 30 kilometre Zone | |

| Exclusion area and disaster area | |

Entrance to the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone at Checkpoint "Dytyatky" | |

| Official name: Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant Zone of Alienation | |

| Named for: The Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant after the disaster | |

| Country | |

|---|---|

| Oblasts | |

| Raions | Ivankiv Raion (includes former Chernobyl Raion), Poliske Raion, Narodychi Raion |

| Borders on | Belarus, Polesie State Radioecological Reserve |

| Cities | Chernobyl, Pripyat, Poliske |

| Landmarks | Kopachi, Red Forest |

| Buildings | Duga radar, Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant and sarcophagus |

| River | Pripyat River |

| Coordinates | 51°18′00″N 30°00′18″E / 51.3°N 30.005°ECoordinates: 51°18′00″N 30°00′18″E / 51.3°N 30.005°E |

| Area | 2,600 km2 (1,004 sq mi) |

| Population | The Exclusion Zone is an "Area of Absolute (Mandatory) Resettlement".

A few hundred samosely have been permitted to remain. Employees of state agencies are resident in the Zone on a temporary basis[1][2] |

| Founded | 27 April 1986 (current borders established circa 1997) |

| Management | State Agency of Ukraine on the Exclusion Zone Management, part of State Emergency Service of Ukraine |

| Government | Government of Ukraine |

| - location | Kiev, Ukraine |

| For public | Not accessible to the public without permission. Permission can be requested in writing in advance[3] or arranged with a tour operator. |

| Timezone | EET (UTC+2) |

| - summer (DST) | EEST (UTC+3) |

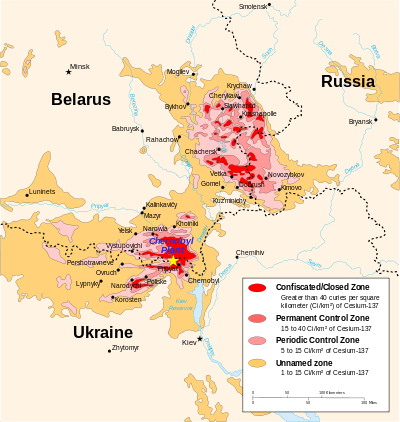

1996 Chernobyl radiation map from CIA - 600 kilometres wide (former border) | |

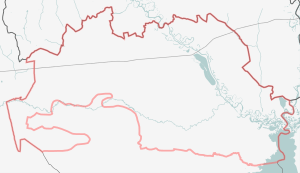

Map of The Zone, in northern Kiev Oblast | |

| Wikimedia Commons: Chernobyl disaster | |

| Website: dazv.gov.ua | |

The Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant Zone of Alienation (Ukrainian: Зона відчуження Чорнобильської АЕС, translit. zona vidchuzhennya Chornobyl's'koyi AES, Russian: Зона отчуждения Чернобыльской АЭС, translit. zona otchuzhdenya Chernobyl'skoyi AES) is an officially designated exclusion zone around the site of the Chernobyl nuclear reactor disaster.[4]:p.4–5:p.49f.3 It is also commonly known as the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone, the 30 Kilometre Zone, or simply The Zone[4]:p.2–5 (Ukrainian: Чорнобильська зона, translit. Chornobyl's'ka zona, Russian: Чернобыльская зона, translit. Chernobyl'skaya zona).

Established by the USSR military soon after the 1986 disaster, it initially existed as an area of 30 km (19 mi) radius from the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant designated for evacuation and placed under military control.[5][6] Its borders have since been altered to cover a larger area of Ukraine. The Chernobyl Exclusion Zone borders a separately administered area, the Polesie State Radioecological Reserve, to the north in Belarus. The Chernobyl Exclusion Zone is managed by an agency of the State Emergency Service of Ukraine, while the power plant and its sarcophagus (and replacement) are administered separately.

The Exclusion Zone covers an area of approximately 2,600 km2 (1,000 sq mi)[7] in Ukraine immediately surrounding the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant where radioactive contamination from nuclear fallout is highest and public access and inhabitation are restricted. Other areas of compulsory resettlement and voluntary relocation not part of the restricted exclusion zone exist in the surrounding areas and throughout Ukraine.[8]

The Exclusion Zone's purpose is to restrict access to hazardous areas, reduce the spread of radiological contamination, and conduct radiological and ecological monitoring activities.[9] Today, the Exclusion Zone is one of the most radioactively contaminated areas in the world and draws significant scientific interest for the high levels of radiation exposure in the environment, as well as increasing interest from tourists.[10]

Geographically, it includes the northernmost raions (districts) of the Kiev and Zhytomyr oblasts (regions) of Ukraine.

History

Before 1986

Historically and geographically, the zone is the heartland of the Polesia region. This predominantly rural woodland and marshland area was once home to 120,000 people living in the cities of Chernobyl and Pripyat as well as 187 smaller communities,[11] but is now mostly uninhabited. All settlements remain designated on geographic maps but marked as нежил. (nezhyl.) – "uninhabited". The woodland in the area around Pripyat was a focal point of partisan resistance during the Second World War, experience of which allowed evacuated residents to evade guards and return.[6] In the woodland near the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant stood the 'Partisan's Tree' or 'Cross Tree', which was used to hang captured partisans. The tree fell down due to age in 1996 and a memorial now stands at its location.

Setup of the Exclusion Zone

10-kilometre and 30-kilometre Zones

The Exclusion Zone was established soon after the Chernobyl disaster on 2 May 1986, when a USSR government commission headed by Nikolai Ryzhkov[7]:4 decided on a "rather arbitrary"[5]:161 area of a 30-kilometre (19 mi) radius from Reactor 4 as the designated evacuation area. The 30 km Zone was initially divided into three subzones: the area immediately adjacent to Reactor 4, an area of approximately 10 km (6 mi) radius from the reactor, and the remaining 30 km zone. Protective clothing and available facilities varied between these subzones.[5]

Later in 1986, after updated maps of the contaminated areas were produced, the zone was split into three areas to designate further evacuation areas based on the revised dose limit of 100 mSv.[7]:4

- the "Black Zone" (over 200 µSv·h−1), to which evacuees were never to return

- the "Red Zone" (50–200 µSv·h−1) where evacuees might return once radiation levels normalized

- the "Blue Zone" (30–50 µSv·h−1) where children and pregnant women were evacuated starting in the summer of 1986

Special permission for access and full military control was put in place in later 1986.[5] Although evacuations were not immediate, 91,200 people were eventually evacuated from these zones.[6]:104

In November 1986, control over activities in the zone was given to the new production association Kombinat. Based in the evacuated city of Chernobyl, the association's responsibility was to operate the power plant, decontaminate the 30 km zone, supply materials and goods to the zone, and construct housing outside the new town of Slavutych for the power plant personnel and their families.[5]:162

In March 1989, a "Safe Living Concept" was created for people living in contaminated zones beyond the Exclusion Zone in Belarus, Ukraine, and Russia.[4]:p.49 In October 1989, the Soviet government requested assistance from the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) to assess the "Soviet Safe Living Concept" for inhabitants of contaminated areas.[4]:p.52 "Throughout the Soviet period, an image of containment was partially achieved through selective resettlements and territorial delineations of contaminated zones."[4]:p.49

After Independence

In February 1991, the law On The Legal Status of the Territory Exposed to the Radioactive Contamination resulting from the ChNPP Accident was passed, updating the borders of the Exclusion Zone and defining obligatory and voluntary resettlement areas, and areas for enhanced monitoring. The borders were based on soil deposits of strontium-90, caesium-137, and plutonium as well as the calculated dose rate (sieverts/h) as identified by the National Commission for Radiation Protection of Ukraine.[12] Responsibility for monitoring and coordination of activities in the Exclusion Zone was given to the Ministry of Chernobyl Affairs.

In-depth studies were conducted from 1992–93, culminating the updating of the 1991 law followed by further evacuations from the Polesia area.[7] A number of evacuation zones were determined: the "Exclusion Zone", the "Zone of Absolute (Mandatory) Resettlement" and the "Zone of Guaranteed Voluntary Resettlement", as well as many areas throughout Ukraine designated as areas for radiation monitoring.[8] The evacuation of contaminated areas outside of the Exclusion Zone continued in both the compulsory and voluntary resettlement areas, with 53,000 people evacuated from areas in Ukraine from 1990 to 1995.[6]

After Ukrainian Independence, funding for the policing and protection of the zone was initially limited, resulting in even further settling by samosely (returnees) and other illegal intrusion.[1][2]

In 1997, the areas of Poliske and Narodychi, which had been evacuated, were added to the existing area of the Exclusion Zone, and the zone now encompasses the exclusion zone and parts of the zone of Absolute (Mandatory) Resettlement of an area of approximately 2,600 km2 (1,000 sq mi).[7] This Zone was placed under management of the 'Administration of the exclusion zone and the zone of absolute (mandatory) resettlement' within the Ministry of Emergencies.

On 15 December 2000, all nuclear power production at the power plant was ceased after an official ceremony with then President Leonid Kuchma when the last remaining operational reactor, number 3, was shut down.[13] Power for the ongoing decommissioning work and the zone is now provided by a newly built oil-fueled power station.

The Exclusion Zone is now evacuated save for a small number of samosely (returnees or self settlers). Areas outside the Exclusion Zone designated for voluntary resettlement continue to be evacuated.

People in the Zone

Population

The zone is estimated to be home to 197 samosely[14] living in 11 villages as well as the town of Pripyat.[15] This number is in decline, down from previous estimates of 314 in 2007 and 1,200 in 1986.[15] These residents are senior citizens, with an average age of 63.[15] After recurrent attempts at expulsion, the authorities became reconciled to their presence and have allowed them limited supporting services. Residents are now informally permitted to stay by the Ukrainian government.

Approximately 3,000 people work in the Zone of Alienation on various tasks, such as the construction of the New Safe Confinement, the ongoing decommissioning of the reactors, and assessment and monitoring of the conditions in the zone. Employees do not live inside the zone, but work shifts there. Some of the workers work "4-3" shifts (four days on, three off), while others work 15 days on, 15 off.[16] Other workers commute into the zone daily from Slavutych. The duration of shifts is counted strictly for reasons involving pension and healthcare. Everyone employed in the Zone is monitored for internal bioaccumulation of radioactive elements.

Chernobyl town, located outside of the 10 km Exclusion Zone, was evacuated following the accident, but now serves as a base to support the workers within the Exclusion Zone. Its amenities include administrative buildings, general stores, a canteen, a hotel, and a bus station. Unlike other areas within the Exclusion Zone, Chernobyl town is actively maintained by workers, such as lawn areas being mowed and autumn leaves being collected.

Access and tourism

There have been growing numbers of visitors to the Exclusion Zone each year, and there are now daily trips from Kiev offered by multiple companies. In addition, multiple day excursions can be easily arranged with Ukrainian tour operators. Most overnight tourists stay in a hotel within the town of Chernobyl, which is located within the Exclusion Zone. According to an exclusion area tour guide, as of 2017, there are approximately 50 licensed exclusion area tour guides in total working for approximately nine companies. Visitors must present their passports when entering the Exclusion Zone, and are screened for radiation when exiting both at the 10 km checkpoint and at the 30 km checkpoint.

The Exclusion Zone can also be entered if an application is made directly to the zone administration department.

Some evacuated residents of Pripyat have established a remembrance tradition, which includes annual visits to former homes and schools.[17] In the Chernobyl zone, there is one operating Eastern Orthodox Christian church, St. Elijah Church, notable for its very low radiation levels, which according to Chernobyl disaster liquidators, are "well below the level across the zone", a fact that president of the Ukrainian Chernobyl Union, Yury Andreyev, considers miraculous.[18][19]

The Chernobyl Exclusion Zone has been accessible to interested parties such as scientists and journalists since the zone was created. An early example was Elena Filatova's online account of her alleged solo bike ride through the zone. This gained her Internet fame, but was later alleged to be fictional, as a guide claimed Filatova was part of an official tour group. Regardless, her story drew the attention of millions to the nuclear catastrophe.[20] After Filatova's visit in 2004, a number of papers such as The Guardian[21] and The New York Times[22] began to produce reports on tours to the zone.

Tourism to the area became more common after Pripyat was featured in popular video games:[23] S.T.A.L.K.E.R.: Shadow of Chernobyl and Call Of Duty 4: Modern Warfare. Fans of the S.T.A.L.K.E.R. franchise, who refer to themselves as "stalkers", often gain access to the Zone.[24] (Both the name "the Zone" and the term "stalker" derive from Andrei Tarkovsky's film Stalker, which predates the Chernobyl disaster but describes a similar setting.) Prosecution of trespassers became more severe after a significant increase in trespassing in the Exclusion Zone. An article in the penal code of Ukraine was specially introduced,[25][26] and horse patrols were added to protect the zone's perimeter.

In 2012, journalist Andrew Blackwell published Visit Sunny Chernobyl: And Other Adventures in the World's Most Polluted Places. Blackwell recounts his visit to the Exclusion Zone, when a guide and driver took him through the zone and to the reactor site.[27]

On 14 April 2013, the 32nd episode of the wildlife documentary TV program River Monsters (Atomic Assassin, Season 5, Episode 2) was broadcast featuring the host Jeremy Wade catching a wels catfish in the cooling pools of the Chernobyl power plant, at the heart of the Exclusion Zone.

On 16 February 2014, an episode of the British motoring TV programme Top Gear was broadcast featuring two of the presenters, Jeremy Clarkson and James May, driving into the Exclusion Zone.

Illegal activities

The poaching of game, illegal logging, and metal salvage have been problems within the zone.[28] Despite police control, intruders started infiltrating the perimeter to remove potentially contaminated materials, from televisions to toilet seats, especially in Pripyat, where the residents of about 30 high-rise apartment buildings had to leave all of their belongings behind. In 2007, the Ukrainian government adopted more severe criminal and administrative penalties for illegal activities in the alienation zone,[29] as well as reinforced units assigned to these tasks. The population of Przewalski's horse, introduced to the Exclusion Zone in 1998,[23] has reportedly fallen since 2005, due to poaching.[30]

Management of the Zone

Administration

| Державне агентство України з управління зоною відчуження | |

|

| |

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | 6 April 2011 |

| Preceding Agency |

|

| Jurisdiction | Government of Ukraine |

| Headquarters | Kiev and Chernobyl |

| Parent department | Ministry of Ecology and Natural Resources |

| Key document |

|

| Website | http://dazv.gov.ua/ |

In April 2011, the State Agency of Ukraine on the Exclusion Zone Management (SAEZ) became the successor to the State Department - Administration of the exclusion zone and the zone of absolute (mandatory) resettlement according to presidential decree.[9] The SAEZ is, as its predecessor, an agency within the State Emergency Service of Ukraine. Policing of the Zone is conducted by special units of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Ukraine and, along the border with Belarus, by the State Border Guard Service of Ukraine. It is partly excluded from regular civil rule. Any residential, civil or business activities in the zone are legally prohibited. The only officially recognized exceptions are the functioning of the Chernobyl nuclear power plant and scientific installations related to the studies of nuclear safety.

The SAEZ is tasked with the following:[9]

- Conducting environmental and radiation monitoring of the Zone;

- Management of long term storage and disposal of radioactive wastes.

- Leases land in the Exclusion Zone and the Zone of absolute (mandatory) resettlement.

- Administers the State Fund of radioactive wastes Management.

- Monitoring and preserving of documentation that describes the subject of radioactive wastes, warning signs, fences, etc.

- Coordinator of the decommissioning of Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant.

- Oversees a register of persons who have suffered as a result of the Chernobyl disaster.

The decree also includes the task to "prevent corruption" (see corruption in Ukraine)

The Chernobyl nuclear power plant is located inside the Zone of Alienation but is administered separately. Plant personnel, 3,800 workers as of 2009, reside primarily in Slavutych, a specially-built remote city in the Kiev Oblast outside of the Exclusion Zone, 45 km (28 mi) east of the accident site.

Checkpoints

There are 11 checkpoints[31]

- Dytiatky, near village Dytyatky

- Stari Sokoly, near village Stari Sokoly

- Zelenyi Mys, near village Strakholissia

- Poliske, near village Chervona Zirka

- Ovruch, near village Davydky

- Vilcha, near village Vilkhova

- Dibrova, near village Fedorivka

- Benivka, near city of Pripyat

- The city of Pripyat itself

- Leliv, near city of Chernobyl

- Paryshiv, between city of Chernobyl and border with Belarus (route P56)

Development and recovery projects

As of 2010, the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone is exclusively environmental recovery area, with efforts devoted to remediation and re-enclosure of the reactor site. Environmental advocates have recommended making less contaminated portions of the site permanently off limits to allow for wildlife recovery and a habitat reserve.[32]

The oldest and most recognized vision of the zone’s future is a research and industrial ground for developing nuclear technologies, including technology of nuclear wastes disposal. Permanent waste facilities are already being constructed in the zone, although these projects suffer from environmental and business concerns.

There are growing calls for wider economic and social revival of the territories around the disaster zone. For instance, special technologies are suggested for agriculture and energy projects that would avoid the danger of proliferating polluted material. The most vocal advocate of such revival was the then President Viktor Yuschenko who has expressed his deep concerns with the exclusion of polluted territories from the society and economy of Ukraine.

In November 2007 the United Nations General Assembly adopted a resolution calling for "recovery and sustainable development" of the areas affected by the Chernobyl accident. Commenting on the issue, UN Development Programme officials mentioned the plans to achieve “self-reliance” of the local population, “agriculture revival” and development of ecotourism.[33]

However, it is not clear whether such plans of UN and Yuschenko deal with the zone of alienation proper, or only with the other three zones around the disaster site where contamination is less intense and restrictions on the population looser (such as the district of Narodychi in Zhytomyrska Oblast).

For several years, tour operators have been bringing tourists inside the 30 km Exclusion Zone. Tourists are accompanied by tour guides at all times and are not able to wander too far on their own due to the presence of several radioactive "hot spots". Tourists can visit the abandoned town of Pripyat and view its overgrown streets.

In 2017, three companies were reported developing plans for solar farms within the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone.[34] The high feed-in tariffs offered, the availability of land, and easy access to transmission lines (which formerly ran to the nuclear power station) have all been noted as beneficial to citing a solar farming.

Radioactive contamination

The territory of the zone is polluted unevenly. Spots of hyperintensive pollution were created first by wind and rain spreading radioactive dust at the time of the accident, and subsequently by numerous burial sites for various material and equipment used in decontamination. Zone authorities pay attention to protecting such spots from tourists, scrap hunters and wildfires, but admit that some dangerous burial sites remain unmapped, and only recorded in the memories of the (aging) Chernobyl liquidators.

Flora and fauna

There has been an ongoing scientific debate about the extent to which flora and fauna of the zone were affected by the radioactive contamination that followed the accident. As noted by Baker and Wickliffe, one of many issues is differentiating between negative effects of Chernobyl radiation, and effects of changes in farming activities resulting from human evacuation.[35]

"Twenty-five years after the Chernobyl meltdown, the scientific community has not yet been able to provide a clear understanding of the spectrum of ecological effects created by that radiological disaster."[35]

Near the facility, a dense cloud of radioactive dust killed off a large area of Scotch pine trees; the rusty orange color of the dead trees led to the nickname "The Red Forest" (Рудий ліс).[35] The Red Forest was among the world's most radioactive places; to reduce the hazard, the Red Forest was bulldozed and the highly irradiated wood was buried, though the soil continues to emit significant radiation.[36][37] Other species in the same area, such as birch trees, survived, indicating that plant species may vary considerably in their sensitivity to radiation.[35]

Cases of mutant deformity in animals of the zone include partial albinism and other external malformations in swallows[38][39][40] and insect mutations.[41] A study of several hundred birds belonging to 48 different species also demonstrated that birds inhabiting highly radioactively contaminated areas had smaller brains compared to birds from clean areas.[42] There have been claims of other animal mutations from individual eyewitness reports, although none have been verified.

A reduction in the density and the abundance of animals in highly radioactively contaminated areas has been reported for several taxa, including birds,[43][44] insects and spiders,[45] and mammals. [46] In birds, which are an efficient bioindicator, a negative correlation has been reported between background radiation and bird species richness.[47] Scientists such as Anders Pape Møller (University of Paris-Sud) and Timothy Mousseau (University of South Carolina) report that birds and smaller animals such as voles may be particularly affected by radioactivity.[48] However, some of their research has been criticized as flawed,[49][50][51] and Møller has faced charges of misconduct.[52]

More recently there have been reports that populations of large mammals have increased due to significant reduction of human interference.[53][48] Some claim that the populations of traditional Polesian animals (such as wolves, badger, wild boar, roe deer, white-tailed eagle, black stork, western marsh harrier, short-eared owl, red deer, moose, great egret, whooper swan, least weasel, common kestrel, and beaver) have multiplied enormously and begun expanding outside the zone.[54][55] The zone is considered by some as a classic example of an involuntary park.[56]

The return of wolves and other animals to the area is being studied by scientists such as Marina Shkvyria (Ukraine’s National Academy of Sciences), Sergey Gaschak (Chernobyl Centre in Ukraine), and Jim Beasley (University of Georgia). Camera traps have been installed and are used to record the presence of species. Studies of wolves, which are concentrated in higher-radiation areas near the center of the exclusion zone, may enable researchers to better assess relationships between radiation levels, animal health, and population dynamics.[23][48]

The area also houses herds of wisent (European bison, native to the area) and Przewalski's horses (foreign to the area, as tarpan was the native wild horse) released there after the accident. Some accounts refer to the reappearance of extremely rare native lynx, and there are videos of brown bears and their cubs, an animal not seen in the area for more than a century.[57] Special game warden units are organized to protect and control them. No scientific study has been conducted on the population dynamics of these species.

The rivers and lakes of the zone pose a significant threat of spreading polluted silt during spring floods. They are systematically secured by dikes.

Grass and forest fires

It is known that fires can make radioactivity mobile again.[58][59][60][61] In particular V.I. Yoschenko et al. reported on the possibility of increased mobility of caesium, strontium, and plutonium due to grass and forest fires.[62] As an experiment, fires were set and the levels of the radioactivity in the air downwind of these fires was measured.

Grass and forest fires have happened inside the contaminated zone, releasing radioactive fallout into the atmosphere. In 1986 a series of fires destroyed 2,336 ha (5,772 acres) of forest, and several other fires have since burned within the 30 km (19 mi) zone. A serious fire in early May 1992 affected 500 ha (1,240 acres) of land, including 270 ha (670 acres) of forest. This resulted in a great increase in the levels of caesium-137 in airborne dust.[58][63][64][65]

In 2010, a series of wildfires affected contaminated areas, specifically the surroundings of Bryansk and border regions with Belarus and Ukraine.[66] The Russian government claims that there has been no discernible increase in radiation levels, while Greenpeace accuses the government of denial.[66]

Current state of the ecosystem

Despite the negative effect of the disaster on human life, many scientists see a likely beneficial effect to the ecosystem. Though the immediate and subsequent effects were devastating, the area quickly recovered and is today seen as very healthy. The lack of people in the area is another factor that has been named as helping to increase the biodiversity of the Exclusion Zone in the years since the disaster.[67]

In the aftermath of the disaster, radiation in the air had a decidedly negative effect on the fauna, vegetation, rivers, lakes, and groundwater of the area. The radiation resulted in deaths among coniferous plants, soil invertebrates, and mammals, as well as a decline in reproductive numbers among both plants and animals.[68]

The surrounding forest was covered in radioactive particles, resulting in the death of 400 hectares of the most immediate pine trees, though radiation damage can be found in an area of tens of thousands of hectares.[69] An additional concern is that as the dead trees in this Red Forest (named for the color of the dead pines) decay, radiation is leaking into the groundwater.[70]

Despite all this, Professor Nick Beresford, an expert on Chernobyl and ecology, said that “the overall effect was positive” for the wildlife in the area.[71] The radiation essentially sped up the evolutionary process, as the area's wildlife had to adapt or die, meaning weaker species who were unable to adapt quickly died off leaving only the stronger members of the ecosystem, ones without growth and reproduction problems.[67]

The impact of radiation on individual animals has not been studied, but cameras in the area have captured evidence of a resurgence of the mammalian population – including rare animals such as the lynx and the endangered European bison.[71]

Research on the health of Chernobyl’s wildlife is ongoing, and there is concern that the wildlife still suffers from some of the negative effects of the radiation exposure. Though it will be years before researchers collect the necessary data to fully understand the effects, for now, the area is essentially one of Europe's largest nature preserves.

Infrastructure

| Ovruch to Chernihiv Line | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The industrial, transport, and residential infrastructure has been largely crumbling since the 1986 evacuation. There are at least 800 known "burial grounds" (Ukrainian singular: mohyl'nyk) for the contaminated vehicles with hundreds of abandoned military vehicles and helicopters. River ships and barges lie in the abandoned port of Chernobyl. The port can easily be seen in satellite images of the area.[72] The Jupiter Factory, one of the largest buildings in the zone, was in use until 1996 but has since been abandoned and its condition is deteriorating.

However, the infrastructure immediately used by the existing nuclear-related installations is maintained and developed, such as the railway link to the outside world from the Semykhody station used by the power plant.[73]

"Chernobyl-2"

The Chernobyl-2 site (a.k.a. "The Russian Woodpecker") is a former Soviet military installation relatively close to the power plant, consisting of a gigantic transmitter and receiver belonging to the Duga-3 over-the-horizon radar system.[74] Located 2 km (1.2 mi) from the surface area of Chernobyl-2 is a large underground complex that was used for anti-missile defense, space surveillance and communication, and research.[75] Military units were stationed there.[75]

Media depictions

- Markiyan Kamysh's novel about Chernobyl illegal trips A Stroll to the Zone was praised by reviewers as the most interesting literature debut in Ukraine.[76] The novel has been translated into French (in title "La Zone"), and was published by French publishing house Arthaud (Groupe Flammarion), and was warmly welcomed by critics and praised in French magazines.[77][78][79]

- The 2015 documentary The Russian Woodpecker, which won the Grand Jury Prize for World Documentary at the Sundance Film Festival,[80] has extensive footage from the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone and focuses on a conspiracy theory behind the disaster and the nearby Duga radar installation

- The 2012 film Chernobyl Diaries is set in the Exclusion Zone. The horror movie follows a tour group that become stranded in Pripyat, and their encounters with creatures mutated by radioactive exposure.

- In 2011, Guillaume Herbaut and Bruno Masi created the web documentary La Zone, funded by CNC, LeMonde.fr and Agat Films. The documentary explores the communities and individuals that still inhabit or visit the Exclusion Zone.[81]

- The PBS program Nature aired on 19 October 2011, its documentary Radioactive Wolves which explores the return to nature which has occurred in the Exclusion Zone among wolves and other wildlife.[82]

- In the 2011 film Transformers: Dark of the Moon, Chernobyl is depicted when the autobots investigate suspected alien activity.

- 2011: the award-winning short film Seven Years of Winter[83][84] was filmed under the direction of Marcus Schwenzel in 2011.[85] In his short film the filmmaker tells the drama of the orphan Andrej, which is sent into the nuclear environment by his brother Artjom in order to ransack the abandoned homes .[86] 2015 the film received the Award for Best Film from the Uranium International Film Festival.[87]

- A 2009 episode of Destination Truth depicts Josh Gates and the Destination Truth team exploring the ruins of Pripyat for signs of paranormal activity.

- The video game series S.T.A.L.K.E.R.: Shadow of Chernobyl, released in 2007, recreates parts of the zone from source photographs and in-person visits (bridges, railways, buildings, compounds, abandoned vehicles), albeit taking some artistic license regarding the geography of the Zone for gameplay reasons.[88]

- In the 2007 video game Call Of Duty 4: Modern Warfare, two missions, i.e. "All Ghillied Up" and "One Shot, One Kill" take place in Pripyat.

- A large fraction of Martin Cruz Smith's 2004 crime novel Wolves Eat Dogs (the fifth in his series starring Russian detective Arkady Renko) is set in the Exclusion Zone.

- 1999: UK photographer John Darwell (born 1955) was among the first foreigners to photograph, for three weeks in late 1999, within the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone, including in Pripyat, in numerous villages, a landfill site, and people continuing to live within the Zone. This resulted in an exhibition and book Legacy: Photographs inside the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone. Stockport: Dewi Lewis, 2001. ISBN 978-1-899235-58-2. Visits have since been made by numerous other documentary and art photographers.

- 1993: the official video for Pink Floyd's "Marooned" features scenes of the town of Pripyat.

- 1986: Immediately after the explosion on 26 April 1986, Russian photographer Igor Kostin (1936–2015) photographed and reported on the event, getting the first pictures from the air, then for the next twenty years he continued visit the area to document the political and personal stories of those impacted by the disaster, publishing a book of photos Chernobyl : confessions of a reporter[89]

- In an episode of Top Gear, the hosts were challenged with making their cars run out of fuel before they could reach the Exclusion Zone.

See also

| Part of a series on the |

| Subdivisions of Ukraine |

|---|

|

| First level (regions) |

| Second level (districts) |

| Third level (communities) |

| Special case administrations |

|

| Populated places in Ukraine |

| Former subdivisions |

|

|

| Classification (KOATUU) |

References

- 1 2 "Чернобыльскую зону "захватывают" самоселы". Ura-inform.com. 28 August 2012. Retrieved 2012-10-22.

- 1 2 "Секреты Чернобыля - "Самоселы"". Chernobylsecret.my1.ru. Retrieved 2012-10-22.

- ↑ "ORDER MOE of Ukraine on November 2, 2011 № 1157 approving the visiting of the exclusion zone and zone of unconditional (mandatory) resettlement". 2 November 2011. Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Petryna, Adriana (2002). Life Exposed: Biological Citizens after Chernobyl. New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-09019-1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Marples, David R. (1988). The Social Impact of the Chernobyl Disaster. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-02432-0.

- 1 2 3 4 Mould, R. F. (2000). Chernobyl Record: The Definitive History of the Chernobyl Catastrophe. Bristol, UK: Institute of Physics Publishing. ISBN 0-7503-0670-X.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bondarkov, Mikhail D.; Oskolkov, Boris Ya.; Gaschak, Sergey P.; Kireev, Sergey I.; Maksimenko, Andrey M.; Proskura, Nikolai I.; Jannik, G. Timothy (2011). Environmental Radiation Monitoring in the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone - History and Results 25 Years After. US: Savannah River National Laboratory / Savannah River Nuclear Solutions.

- 1 2 "Zoning of radioactively contaminated territory of Ukraine according to actual regulations". ICRIN. 2004. Archived from the original on 18 February 2013. Retrieved 25 April 2012.

- 1 2 3 "Decree of the President of Ukraine № 393/2011 On approval of the State Agency of Ukraine of the Exclusion Zone". State Agency of Ukraine on Exclusion Zone Management. 6 April 2011. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- ↑ "Postcard from hell". The Guardian. 18 October 2004. Archived from the original on 28 October 2017. Retrieved 25 April 2012.

- ↑ "IAEA Frequently Asked Chernobyl Questions". International Atomic Energy Agency. Archived from the original on 23 February 2011. Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- ↑ Nasvit, Oleg (1998). "Legislation in Ukraine about the Radiological Consequences of the Chernobyl Accident" (PDF). Research Activities about the Radiological Consequences of the Chernobyl NPS Accideent and Social Activities to Assist the Sufferers by the Accident, KURRI-KR-21, Research Reactor Institute, Kyoto University 注. 25: 51–57.

- ↑ "IAEA's Power Reactor Information System polled in May 2008 reports shut down for units 1, 2, 3 and 4 respectively". Retrieved 25 April 2012.

- ↑ URA-Inform (28 August 2012). "ChernobylZone squatter captured" (in Russian). URS-Inform. Retrieved 11 December 2012.

- 1 2 3 Marples, David (3 May 2012). "Chornobyl's legacy in Ukraine: Beyond the United Nations reports". Kyiv Post. Archived from the original on 21 January 2016. Retrieved 11 December 2012.

- ↑ Rothbart, Michael. "After Chernobyl". Retrieved 11 December 2012.

- ↑ "Сайт г. Припять. Чернобыльская авария. Фото Чернобыль. Чернобыльская катастрофа". Pripyat.com. Retrieved 2015-10-31.

- ↑ "The only church open in Chernobyl zone shows the minimum radiation level". Interfax. 20 April 2011. Retrieved 29 April 2014.

Kiev, April 20, Interfax - During 25 years from the date of Chernobyl accident the radiation level in the area of St. Elijah Church, the only church operating in the exclusion zone, was well below the level across the zone, Chernobyl disaster liquidators state. "Even in the hardest days of nineteen eighty six the area around St. Elijah Church was clean (from radiation - IF), not to mention that the church itself was also clean," president of the Ukrainian Chernobyl Union Yury Andreyev said in a Kiev-Moscow video conference on Wednesday. Now the territory adjacent to the church has the background level of 6 microroentgen per hour compared with 18 in Kiev. Andreyev also said many disaster liquidators had been atheists. "We came to believe later after observing such developments which could be explained only by God's will," he says.

- ↑ "The only church open in Chernobyl zone shows the minimum radiation level". Kiev: Pravoslavie. 21 April 2011. Retrieved 29 April 2014.

- ↑ Mycio, Mary (6 July 2004). "Account of Chernobyl Trip Takes Web Surfers for a Ride". Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ "Chernobyl: Ukraine's new tourist destination | World news". The Guardian. 18 October 2004. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

- ↑ Chivers, C.J. (15 June 2005). "Pripyat Journal; New Sight in Chernobyl's Dead Zone: Tourists". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 24 February 2011.

- 1 2 3 Boyle, Rebecca (Fall 2017). "Greetings from Isotopia". Distillations. 3 (3): 26–35. Retrieved June 19, 2018.

- ↑ Archived 5 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Кримінальний кодекс України | від 05.04.2001 № 2341-III (Сторінка 7 з 14)" (in Russian). Zakon.rada.gov.ua. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

- ↑ "Кодекс України про адміністративні правопорушення (ст... | від 07.12.1984 № 8073-X (Сторінка 2 з 15)" (in Russian). Zakon.rada.gov.ua. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

- ↑ Blackwell, Andrew (2012). Visit Sunny Chernobyl: And Other Adventures in the World's Most Polluted Places. Rodale Books. p. 320. ISBN 978-1-60529-445-2.

- ↑ Davies, Thom; Polese, Abel (2015). "Informality and survival in Ukraine's nuclear landscape: Living with the risks of Chernobyl". Journal of Eurasian Studies. 6 (1): 34–45. doi:10.1016/j.euras.2014.09.002. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

- ↑ "Желающие привезти сувениры из Чернобыля станут уголовниками" (in Russian). Korrespondent.net. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

- ↑ Gill, Victoria (27 July 2011). "Chernobyl's Przewalski's horses are poached for meat". BBC Nature News. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

- ↑ "Границы и КПП". Google Maps. Retrieved 15 June 2017.

- ↑ Baker, Robert J.; Chesser, Roland K. (2000). "The Chernobyl Nuclear Disaster And Subsequent Creation of a Wildlife Preserve". Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry. 19 (5): 1231–1232. Retrieved 14 August 2010.

- ↑ "UN plots Chernobyl zone recovery". BBC News. 21 November 2007. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

- ↑ Geuss, Megan (28 November 2017). "Radioactive land around Chernobyl to sprout solar investments". Ars Technica. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 Baker, Robert J.; Wickliffe, Jeffrey K. (14 April 2011). "Wildlife and Chernobyl: The scientific evidence for minimal impacts". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- ↑ Bird, Winifred A.; Little, Jane Braxton (March 2013). "A Tale of Two Forests: Addressing Postnuclear Radiation at Chernobyl and Fukushima". Environmental Health Perspectives. 121 (3). Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- ↑ Mycio, M. (2005). Wormwood Forest: A Natural History of Chernobyl. Washington, DC: Joseph Henry Press.

- ↑ Møller, A. P.; Mousseau, T. A. (October 2001). "Albinism and phenotype of barn swallows (Hirundo rustica) from Chernobyl". Evolution. 55 (10): 2097–2104. doi:10.1554/0014-3820(2001)055[2097:aapobs]2.0.co;2. PMID 11761068.

- ↑ Møller, A. P.; Mousseau, T. A.; de Lope, F.; Saino, N. (22 August 2007). "Elevated frequency of abnormalities in barn swallows from Chernobyl" (PDF). Biology Letters. 3 (4): 414–417. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2007.0136. PMC 1994720. PMID 17439847.

- ↑ Kinver, Mark (14 August 2007). "Chernobyl 'not a wildlife haven'". BBC News. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

- ↑ "Cornelia Hesse Honegger: Aktuelles". Wissenskunst.ch. Retrieved 2015-10-31.

- ↑ Møller, Anders Pape; Bonisoli-Alquati, Andea; Rudolfsen, Geir; Mousseau, Timothy A. (2011). "Chernobyl Birds Have Smaller Brains". PLoS ONE. 6 (2): e16862. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0016862. PMC 3033907. PMID 21390202.

- ↑ Møller, A. P.; Mousseau, T. A. (22 October 2007). "Species richness and abundance of forest birds in relation to radiation at Chernobyl". Biology Letters. 3 (5): 483–486. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2007.0226. PMC 2394539. PMID 17698449.

- ↑ Møller, A. P.; T. A. Mousseau (January 2009). "Reduced abundance of raptors in radioactively contaminated areas near Chernobyl". Journal of Ornithology. 150 (1): 239–246. doi:10.1007/s10336-008-0343-5.

- ↑ Møller, Anders Pape; Mousseau, Timothy A. (2009). "Reduced abundance of insects and spiders linked to radiation at Chernobyl 20 years after the accident" (PDF). Biology Letters (published 18 March 2009). 5 (3): 356–359. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2008.0778. PMC 2679916. PMID 19324644.

- ↑ Møller, Anders Pape; Mousseau, Timothy A. (March 2011). "Efficiency of bio-indicators for low-level radiation under field conditions". Ecological Indicators. 11 (2): 424–430. doi:10.1016/j.ecolind.2010.06.013.

- ↑ Morelli, Federico; Mousseau, Timothy A.; Møller, Anders Pape (October 2017). "Cuckoos vs. top predators as prime bioindicators of biodiversity in disturbed environments". Journal of Environmental Radioactivity. 177: 158–164. doi:10.1016/j.jenvrad.2017.06.029. PMID 28686944.

- 1 2 3 Wendle, John (18 April 2016). "Animals Rule Chernobyl Three Decades After Nuclear Disaster". National Geographic. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- ↑ Barras, Colin (22 April 2016). "The Chernobyl exclusion zone is arguably a nature preserve". BBC Earth. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- ↑ Borrell, Brendan (24 March 2009). "Scientific meltdown at Chernobyl?". Scientific American News Blog. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- ↑ Higginbotham, Adam (14 April 2011). "Is Chernobyl a Wild Kingdom or a Radioactive Den of Decay?". Wired. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- ↑ Vogel, Gretchen; Proffitt, Fiona; Stone, Richard (28 January 2004). "Ecologists Rocked by Misconduct Finding". Science. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- ↑ Mulvey, Stephen (20 April 2006). "Wildlife defies Chernobyl radiation". BBC News. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

- ↑ Lavars, Nick (6 October 2015). "Deer, wolves and other wildlife thriving in Chernobyl exclusion zone". New Atlas. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- ↑ Deryabina, T.G.; Kuchmel, S.V.; Nagorskaya, L.L.; Hinton, T.G.; Beasley, J.C.; Lerebours, A.; Smith, J.T. (October 2015). "Long-term census data reveal abundant wildlife populations at Chernobyl". Current Biology. 25 (19): R824–R826. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2015.08.017. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- ↑ "Conflict conservation". The Economist. 8 February 2010. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- ↑ Kinver, Mark (26 April 2015). "Cameras reveal the secret lives of Chernobyl's wildlife". BBC News. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- 1 2 Dusha-Gudym, Sergei I. (August 1992). "Forest Fires on the Areas Contaminated by Radionuclides from the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant Accident". IFFN. Global Fire Monitoring Center (GFMC). pp. No. , 7, p. , 4–6. Retrieved 2008-06-18.

- ↑ "Forest Fire as a Factor of Environmental Redistribution of Radionuclides Originating from Chernobyl Accident" (PDF). Maik.ru. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 March 2009. Retrieved 2015-10-31.

- ↑ Davidenko, Eduard P.; Johann Georg Goldammer (January 1994). "News from the Forest Fire Situation in the Radioactively Contaminated Regions".

- ↑ Antonov, Mikhail; Maria Gousseva (18 September 2002). "Radioactive fires threaten Russia and Europe". Pravda.ru. Archived from the original on 2 May 2009.

- ↑ Yoschenko; et al. (2006). "Resuspension and redistribution of radionuclides during grassland and forest fires in the Chernobyl exclusion zone: part I. Fire experiments". Journal of Environmental Radioactivity. 86: 143–163. doi:10.1016/j.jenvrad.2005.08.003. PMID 16213067.

- ↑ "Transport of Radioactive Materials by Wildland fires in the Chernobyl Accident Zone: How to Address the Problem" (PDF). (416 KB)

- ↑ "Chernobyl Forests. Two Decades After the Contamination" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 June 2007. (139 KB)

- ↑ Allard, Gillian. "Fire prevention in radiation contaminated forests". Forestry Department, FAO. Retrieved 2008-06-18.

- 1 2 Deutsche Welle (11 August 2010). "Russian fires hit Chernobyl-affected areas, threatening recontamination".

- 1 2 Hopkin, Michael (9 August 2005). "Chernobyl ecosystems 'remarkably healthy'". Nature News. doi:10.1038/news050808-4. Retrieved 15 June 2017 – via www.Nature.com.

- ↑ WHO. (2005). Chernobyl: the true scale of the accident.

- ↑ "Red forest: description of radioactive dead ecosystem | Чернобыль, Припять, зона отчуждения ЧАЭС". chornobyl.in.ua. Retrieved 2017-06-22.

- ↑ Onishi, Yasuo; Voitsekhovich, Oleg V.; Zheleznyak, Mark J. (3 June 2007). "Chapter 2.6 - Radionucleotides in Groundwater in the CEZ". Chernobyl - What Have We Learned?: The Successes and Failures to Mitigate Water Contamination Over 20 Years. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9781402053498.

- 1 2 Oliphant, Roland (24 April 2016). "30 years after Chernobyl disaster, wildlife is flourishing in radioactive wasteland". Telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 8 January 2018.

“You could say that the overall affect was positive,” said Professor Nick Beresford, an expert on Chernobyl based at the centre for Ecology and hydrology in Lancaster.

- ↑ "Exploring Chernobyl Dead Zone With Google Maps | The Cheap Route". Blog.TheCheapRoute.com. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

- ↑ "A journey through the Chornobyl Exclusion Zone". Radioactive Railroad. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

- ↑ Archived 21 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 Wolfgang Spyra. Environmental Security and Public Safety. Springer, 6 March 2007. pg. 181

- ↑ "Після Сталкера". ЛітАкцент - світ сучасної літератури (in Ukrainian). 6 November 2015. Retrieved 2017-10-02.

- ↑ "Reportage dans la zone interdite de Tchernobyl". Les Inrocks (in French). Retrieved 2017-10-02.

- ↑ "Culture Sélection de mai - Monaco Hebdo". Monaco Hebdo (in French). 12 May 2016. Retrieved 2017-10-02.

- ↑ "Tchernobyl 30 ans après : au coeur de la zone interdite". L'Obs (in French). Retrieved 2017-10-02.

- ↑ Sundance Film Review: The Russian Woodpecker

- ↑ ""La Zone", lauréat du Prix France 24 - RFI du webdocumentaire 2011". Lemonde.fr. 22 April 2011. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

- ↑ "Video: Radioactive Wolves | Watch Nature Online | PBS Video". Video.pbs.org. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

- ↑ "Watch SEVEN YEARS OF WINTER Online | Vimeo On Demand". Vimeo. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

- ↑ "The Film Corner with Greg Klymkiw: SEVEN YEARS OF WINTER - Review By Greg Klymkiw - One of the Best Short Dramatic Films I've Seen In Years is playing at the Canadian Film Centre World Wide Short Film Festival 2012 (Toronto) in the programme entitled "Official Selection: Homeland Security"". klymkiwfilmcorner.blogspot.de. Retrieved 2016-05-03.

- ↑ "IMDb Resume for Marcus Schwenzel". IMDb. Retrieved 2016-05-03.

- ↑ "Zoom - Seven Years of Winter". ARTE Cinema. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

- ↑ "Award to Seven Years of Winter | International Uranium Film Festival". uraniumfilmfestival.org. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

- ↑ "S.T.A.L.K.E.R.: Shadow of Chernobyl". Stalker-game.com. 13 February 2007. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

- ↑ Kostin, Igor; Johnson, Thomas (2006), Chernobyl : confessions of a reporter, New York Umbrage Editions, ISBN 978-1-884167-57-7

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chernobyl Exclusion Zone. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Chernobyl. |

News and publications

BBC's ongoing coverage

- Chernobyl's legacy recorded in trees by the BBC

- Chernobyl mammals tracked in snow by the BBC

- Wildlife defies Chernobyl radiation - by BBC News, 20 April 2006

Other reliable sources

- Radioactive Wolves - by PBS Documentary aired in the U.S. on Oct, 19 2011

- Picnic in the Death Zone - TV Documentary following Chernobyl scientists as they hunt for radioactive animals deep in the alienation zone

- Inside the Forbidden Forests 1993 The Guardian article about the zone

- The zone as a wildlife reserve

Images from inside the Zone

- ChernobylGallery.com - Photographs of Chernobyl and Pripyat

- Lacourphotos.com - Pripyat in Wintertime (Urban photos)

- Panoramio.com - photos from Panoramio users

- Images from inside the Zone

- Slide show of a visit to the Zone in April 2006 by a German TV team joint by Research Center Juelich