Writings of Cicero

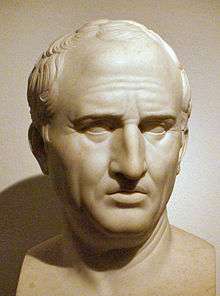

| Marcus Tullius Cicero | |

|---|---|

Marcus Tullius Cicero | |

| Born |

January 3, 106 BC Arpinum, Italy |

| Died |

December 7, 43 BC Formia, Italy |

| Occupation | Politician, lawyer, orator and philosopher |

| Nationality | Ancient Roman |

| Subject | politics, law, philosophy, oratory |

| Literary movement | Golden Age Latin |

| Notable works |

Orations: In Verrem, In Catilinam I–IV, Philippicae Philosophy: De Oratore, De Re Publica, De Legibus, De Finibus, De Natura Deorum, De Officiis |

The writings of Marcus Tullius Cicero constitute one of the most famous bodies of historical and philosophical work in all of classical antiquity. Cicero, a Roman statesman, lawyer, political theorist, philosopher, and Roman constitutionalist, lived from 106 to 43 BC. He was a Roman senator and consul (chief-magistrate) who played a critical role in the transformation of the Roman Republic into the Roman Empire. A contemporary of Julius Caesar, Cicero is widely considered one of Rome's greatest orators and prose stylists.[1][2]

Cicero is generally held to be one of the most versatile minds of ancient Rome. He introduced the Romans to the chief schools of Greek philosophy and created a Latin philosophical vocabulary, distinguishing himself as a linguist, translator, and philosopher. An impressive orator and successful lawyer, Cicero probably thought his political career his most important achievement. Today, he is appreciated primarily for his humanism and philosophical and political writings. His voluminous correspondence, much of it addressed to his friend Atticus, has been especially influential, introducing the art of refined letter writing to European culture. Cornelius Nepos, the 1st-century BC biographer of Atticus, remarked that Cicero's letters to Atticus contained such a wealth of detail "concerning the inclinations of leading men, the faults of the generals, and the revolutions in the government" that their reader had little need for a history of the period.[3]

During the chaotic latter half of the first century BC, marked by civil wars and the dictatorship of Gaius Julius Caesar, Cicero championed a return to the traditional republican government. However, his career as a statesman was marked by inconsistencies and a tendency to shift his position in response to changes in the political climate. His indecision may be attributed to his sensitive and impressionable personality; he was prone to overreaction in the face of political and private change. "Would that he had been able to endure prosperity with greater self-control and adversity with more fortitude!" wrote C. Asinius Pollio, a contemporary Roman statesman and historian.[4][5]

Works

Cicero was declared a "righteous pagan" by the early Catholic Church, and therefore many of his works were deemed worthy of preservation. Saint Augustine and others quoted liberally from his works "On the Commonwealth" (also known as "On the Republic") and "On the Laws," and it is due to this that we are able to recreate much of the work from the surviving fragments. Cicero also articulated an early, abstract conceptualisation of rights, based on ancient law and custom.

Books

Of Cicero's books, six on rhetoric have survived, as well as parts of eight on philosophy.

Speeches

Of his speeches, eighty-eight were recorded, fifty-two of which survive today. Some of the items below include more than one speech.

- Judicial speeches

- (81 BC) Pro Quinctio (On behalf of Publius Quinctius)

- (80 BC) Pro Roscio Amerino (In Defense of Sextus Roscius of Ameria)

- (77 BC) Pro Q. Roscio Comoedo (In Defense of Quintus Roscius Gallus the Comic actor)

- (70 BC) Divinatio in Caecilium (Against Quintus Caecilius in the process for selecting a prosecutor of Gaius Verres)

- (70 BC) In Verrem (Against Gaius Verres, or The Verrines)

- (71 BC) Pro Tullio (On behalf of Tullius)

- (69 BC) Pro Fonteio (On behalf of Marcus Fonteius)

- (69 BC) Pro Caecina (On behalf of Caecina)

- (66 BC) Pro Cluentio (On behalf of Aulus Cluentius)

- (63 BC) Pro Rabirio Perduellionis Reo (On behalf of Gaius Rabirius on a Charge of Treason)

- (63 BC) Pro Murena (In Defense of Lucius Licinius Murena, in the court for electoral bribery)

- (62 BC) Pro Sulla (In Defense of Publius Cornelius Sulla)

- (62 BC) Pro Archia Poeta (In Defense of Aulus Licinius Archias the poet)

- (59 BC) Pro Antonio (In Defense of Gaius Antonius) [lost entire, or never written]

- (59 BC) Pro Flacco (In Defense of Lucius Valerius Flaccus, in the court for extortion)

- (56 BC) Pro Sestio (In Defense of Publius Sestius)

- (56 BC) In Vatinium testem (Against the witness Publius Vatinius at the trial of Sestius)

- (56 BC) Pro Caelio (In Defense of Marcus Caelius Rufus): English translation

- (56 BC) Pro Balbo (In Defense of Lucius Cornelius Balbus)

- (54 BC) Pro Plancio (In Defense of Gnaeus Plancius)

- (54 BC) Pro Rabirio Postumo (In Defense of Gaius Rabirius Postumus)

- (54 BC) Pro Scauro (In Defense of Marcus Aemilius Scaurus)

Several of Cicero's speeches are printed, in English translation, in the Penguin Classics edition Murder Trials. These speeches are included:

- In defence of Sextus Roscius of Ameria (This is the basis for Steven Saylor's novel Roman Blood.)

- In defence of Aulus Cluentius Habitus

- In defence of Gaius Rabirius"

- Note on the speeches in defence of Caelius and Milo

- In defence of King Deiotarus

- Political speeches

- Early career (before exile)

- (66 BC) Pro Lege Manilia or De Imperio Cn. Pompei (in favor of the Lex Manilia on the command of Pompey)

- (64 BC) In Toga Candida (Denouncing candidates for the consulship of 63 BC)

- (63 BC) De Lege Agraria contra Rullum (Opposing the Agrarian Law proposed by Rullus)

- (63 BC) In Catilinam I-IV (Catiline Orations or Against Catiline) Archived March 2, 2005, at the Wayback Machine.

- (59 BC) Pro Flacco (In Defense of Flaccus)

- Mid career (between exile and Caesarian Civil War)

- (57 BC) Post Reditum in Quirites (To the Citizens after his recall from exile)

- (57 BC) Post Reditum in Senatu (To the Senate after his recall from exile)

- (57 BC) De Domo Sua (On his House)

- (57 BC) De Haruspicum Responsis (On the Responses of the Haruspices)

- (56 BC) De Provinciis Consularibus (On the Consular Provinces)

- (55 BC) In Pisonem (Against Piso)

- (52 BC) Pro Milone (In Defence of Titus Annius Milo)

- Late career

- (46 BC) Pro Marcello (On behalf of Marcellus)

- (46 BC) Pro Ligario (On behalf of Ligarius before Caesar)

- (46 BC) Pro Rege Deiotaro (On behalf of King Deiotarus before Caesar)

- (44 BC) Philippicae (consisting of the 14 philippics, Philippica I–XIV, against Marcus Antonius)[6]

(The Pro Marcello, Pro Ligario, and Pro Rege Deiotaro are collectively known as "The Caesarian speeches").

Rhetoric and politics

- (84 BC) De Inventione (About the composition of arguments)

- (55 BC) De Oratore ad Quintum fratrem libri tres (On the Orator, three books for his brother Quintus)

- (54 BC) De Partitionibus Oratoriae (About the subdivisions of oratory)

- (52 BC) De Optimo Genere Oratorum (About the Best Kind of Orators)

- (51 BC) De Re Publica (On the Republic, also known as "On the Commonwealth", and referred to as such, above)

- (46 BC) Brutus (For Brutus, a short history of Roman rhetoric and orators dedicated to Marcus Junius Brutus)

- (46 BC) Orator ad M. Brutum (About the Orator, also dedicated to Brutus)

- (44 BC) Topica (Topics of argumentation)

- (?? BC) De Legibus (On the Laws)

- (?? BC) De Consulatu Suo (On his ((Cicero's)) consulship – epic poem, only parts survive)

- (?? BC) De temporibus suis (His Life and Times – epic poem, entirely lost)

Spuria

Several works extant through having been included in influential collections of Ciceronian texts exhibit such divergent views and styles that they have long been agreed by experts not to be authentic works of Cicero. They are also never mentioned by Cicero himself, nor any of the ancient critics or grammarians who commonly refer to and quote passages from Cicero's authentic works.

- (late 80s BC) Rhetorica ad Herennium (authored by a pro-Marian orator of the mid to late 80s BC sympathetic to the tribune Publius Sulpicius Rufus; perhaps Publius Canutius)

- (60s BC) Commentariolum Petitionis (Note-book for winning elections)[7] (often attributed to Cicero's brother Quintus)

Philosophy

- (46 BC) Paradoxa Stoicorum (Stoic Paradoxes)

- (45 BC) Hortensius

- (45 BC) Lucullus or Academica Priora – Liber Secundus (Second Book of the Prior Academics)

- (45 BC) Varro or Academica Posteriora (Posterior Academics)

- (45 BC) Consolatio (Consolation) How to console oneself at the death of a loved person (see Consolatio)

- (45 BC) De Finibus Bonorum et Malorum (About the Ends of Goods and Evils) – a book on ethics[8]

- (45 BC) Tusculanae Quaestiones (Questions debated at Tusculum)

- (45 BC) De Natura Deorum (On the Nature of the Gods)

- (45 BC) De Divinatione (On Divination)

- (45 BC) De Fato (On Fate)

- (44 BC) Cato Maior de Senectute (Cato the Elder on Old Age)

- (44 BC) Laelius de Amicitia (Laelius on Friendship)

- (44 BC) De Officiis (On Duties)

Letters

Cicero's letters to and from various public and private figures are considered some of the most reliable sources of information for the people and events surrounding the fall of the Roman Republic. While 37 books of his letters have survived into modern times, 35 more books were known to antiquity that have since been lost. These included letters to Caesar, to Pompey, to Octavian, and to his son Marcus.[9]

- Epistulae ad Atticum (Letters to Atticus; 68–43 BC)

- Epistulae ad Brutum (Letters to Brutus; 43 BC)

- Epistulae ad Familiares (Letters to friends; 62–43 BC)

- Epistulae ad Quintum Fratrem (Letters to his brother Quintus; 60/59–54 BC)

See also

|

Notes

- ↑ Rawson, E.: Cicero, a portrait (1975) p. 303

- ↑ Haskell, H.J.: This was Cicero (1964) pp. 300–01

- ↑ Cornelius Nepos, Atticus 16, trans. John Selby Watson.

- ↑ Haskell, H.J.:"This was Cicero" (1964) p. 296

- ↑ Castren and Pietilä-Castren: "Antiikin käsikirja" /"Handbook of antiquity" (2000) p. 237

- ↑ M. Tullius Cicero, Orations: The fourteen orations against Marcus Antonius (Philippics) (ed. C. D. Yonge)

- ↑ M. Tullius Cicero, Letters (ed. Evelyn Shuckburgh)

- ↑ Epicurus.info : E-Texts : De Finibus, Book I

- ↑

References

Critical editions and translations

Teubner editions (Bibliotheca Teubneriana), B. G. Teubner, Stuttgart and Leipzig

- Epistulae ad Atticum (ed.) D R Shackleton-Bailey

- Vol.I: Libri I–VIII (BT 1208, 1987)

- Vol.II: Libri IX–XVI (BT 1209, 1987)

- Epistulae ad Familiares libri I–XVI (ed.) D R Shackleton-Bailey (BT 1210, 1988)

- Epistulae ad Quintum fratrem. Epistulae ad M. Brutum. Commentariolum petitionis. Fragmenta epistolarum (ed.) D R Shackleton-Bailey (BT 1211, 1988)

- Cicero, Marcus Tullius, Cicero’s letters to Atticus, Vol. I, II, IV, VI, Cambridge University Press, Great Britain, 1965

- Cicero, Marcus Tullius, Latin extracts of Cicero on Himself, translated by Charles Gordon Cooper, University of Queensland Press, Brisbane, 1963

- Crawford, Jane W:

- M. Tullius Cicero: The Lost and Unpublished Orations (Hypomnemata Untersuchungen zur Antike und zu Ihrem Nachleben, Heft 80, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen, 1984) ISBN 3-525-25178-5

- M. Tullius Cicero: The Fragmentary Speeches, an Edition with Commentary, 2nd edition (American Philological Association, American Classical Studies no. 37, Scholars Press, Atlanta, 1994) ISBN 0-7885-0076-7

Penguin Classics English translations

- Cicero

- Selected Political Speeches (Penguin Books, 1969)

- Selected Works: Against Verres I, Twenty-three letters, The Second Philippic against Antony, On Duties III, On Old Age, by Michael Grant (Penguin Books, 1960)

- On Government: Against Verres II 5, For Murena, For Balbus, On the State III, V, VI, On Laws III, The Brutus, The Philippics IV, V, X, by Michael Grant (Penguin Books, 1993)

- Plutarch, Fall of the Roman Republic, Six Lives by Plutarch: Marius, Sulla, Crassus, Pompey, Caesar, Cicero, by Rex Warner (Penguin Books, 1958; with Introduction and notes by Robin Seager, 1972)

Modern works

- Taylor, H: Cicero: A sketch of his life and works (A. C. McClurg & Co., Chicago, 1918)

- Strachan-Davidson, J. L., Cicero and the Fall of the Roman Republic, University of Oxford Press, London, 1936

- Cowell, Cicero and the Roman Republic, Penguin Books Ltd, Great Britain, 1973

- Haskell, H.J.: (1946) This was Cicero, Fawcett publications, Inc. Greenwich, Conn.

- Smith, R E: Cicero the Statesman (Cambridge University Press, 1966)

- Gruen, Erich S: The last Generation of the Roman Republic (University of California Press, 1974)

- Rawson, Elizabeth: Cicero, A portrait (Allen Lane, Penguin Books, 1975) ISBN 0-7139-0864-5

- Kinsey, T E: "Cicero's case against Magnus, Capito and Chrysogonus in the pro Sex. Roscio Amerino and its use for the historian", L'Ant.Classique 49 (1980), 173–190

- Frier, Bruce W: The Rise of the Roman Jurists: Studies in Cicero's Pro Caecina, (Princeton University Press, 1985) ISBN 0-691-03578-4

- March, Duane A: "Cicero and the 'Gang of Five'", Classical World 82 (1989), 225–234

- Shackleton-Bailey, D R: Onomasticon to Cicero's Speeches, 2nd edition (Teubner, Stuttgart & Leipzig, 1992)

- Gotoff, Harold C: Cicero's Caesarian Speeches: A Stylistic Commentary (The University of North Carolina Press, 1993) ISBN 0-8078-4407-1

- Everitt, Anthony: Cicero: the life and times of Rome's greatest politician (Random House, 2001) hardback, 359 pages, ISBN 0-375-50746-9

- Manuwald, Gesine: "Performance and Rhetoric in Cicero's Philippics", Antichthon 38 (2004[2006]), 51–69

Further reading

- Francis A. Yates (1974). The Art of Memory, University of Chicago Press, 448 pages, Reprint: ISBN 0-226-95001-8

- Taylor Caldwell (1965), A Pillar of Iron, Doubleday & Company, Reprint: ISBN 0-385-05303-7

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Writings of Marcus Tullius Cicero. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Latin Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Writings of Cicero |

- General:

- Quotes with Cicero's teachings on oratory

- Links to Cicero resources

- University of Texas Cicero Homepage

- "Cicero" article by Edward Clayton in the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Works by Cicero:

- List of online translations of Cicero's works

- Online Library of Liberty

- Works by Cicero at Project Gutenberg

- Perseus Project (Latin and English): Classics Collection (see: M. Tullius Cicero)

- Works of Cicero, The Latin Library

- UAH (Latin, with translation notes): Cicero Page

- De Officiis, translated by Walter Miller

- Cicero's works: text, concordances and frequency list

- Critical Editions and Translations of the Philosophical Works of Cicero

- Biographies and descriptions of Cicero's time:

- At Project Gutenberg

- Plutarch's biography of Cicero contained in the Parallel Lives

- Life of Cicero by Anthony Trollope, Volume I – Volume II

- Cicero by Rev. W. Lucas Collins (Ancient Classics for English Readers)

- Roman life in the days of Cicero by Rev. Alfred J. Church

- Social life at Rome in the Age of Cicero by W. Warde Fowler

- At Heraklia website

- Dryden's translation of Cicero from Plutarch's Parallel Lives

- At Middlebury College website

- At Project Gutenberg

- SORGLL: Cicero, In Catilinam I.1–3, read by Robert Sonkowsky