Women of the Bauhaus

The Bauhaus was seen as a progressive academic institution, as it declared equality amongst the sexes and accepted both male and female students into its programs.[1] During a period in which women had previously been denied from other formal art academies, the Bauhaus provided women with an unprecedented level of opportunity for both education and artistic development.[2] The Bauhaus was founded by the architect, Walter Gropius, in 1919 and operated until 1933. The school's main objective was the unification of the arts.[3] More specifically, the Bauhaus taught a combination of fine arts and design theory, in order to produce artists that were equipped to create both practical and aesthetically pleasing works that catered to the increasingly industrial world.[3] The school had a significant impact on the development of art, architecture, graphic design, interior design, industrial design and typography.

Brief History of the Bauhaus

At the Bauhaus’s inception, the school was located in Weimar.[3] In the Bauhaus’s first year, more female students applied than male students, and the accepted students came from a variety of socio-economic and educational backgrounds.[1] The curriculum began with a technical introduction to the arts through a study of materials, colour theory, and formal relationships, which were meant to prepare the students for their later studies in their specialized programs.[3] Initially, most female students specialized in the disciplines of weaving or ceramics. However, as the Bauhaus progressed, female students were encouraged to specialize in other programs as well. This shift in the specialization of female students was predominantly facilitated by the radical Hungarian artist, László Moholy-Nagy, who became a part of the Bauhaus’s administration in 1923.[4] In 1925, the Bauhaus moved to Dessau, where Gropius designed a new building for the school, which encompassed the fundamental design theory of the Bauhaus.[3] In 1928, Gropius stepped down as director, and was succeeded by the architect, Hannes Meyer. A few years later, the increasingly conservative municipal government forced Meyer to resign and replaced him with Ludwig Mies van der Rohe.[3] In 1932, the school moved once again to Berlin. Due to the various changes in location and leadership, the Bauhaus school's artistic and political objectives continuously shifted, which caused the school to become financially unstable.[3] Additionally, due to the increasing political pressures of the anti-modernist Nazi government, the Bauhaus shut down in 1933.[3]

Some Key Female Artists

[3]Anni Albers was born in Berlin on June 12, 1899. She grew up in an affluent family, and became interested in the visual arts at an early age. She produced many of her own drawings and paintings, while studying under impressionist artist, Martin Brandenburg. Despite the traditional views of her family, she left the domestic life to pursue a career in art.[5] Albers attended the Bauhaus as a young student in 1922, where she specialized in weaving.[5] In her career, she successfully merged textile crafts with industrial production and abstract modernist design, which brought unity to the three areas.[2] Albers died May 9, 1994.

Marianne Brandt was born in Chemnitz on October 1, 1893. Initially, Brandt was trained as a painter, but became the first woman admitted into the metalworking program at the Bauhaus. Brandt studied under Moholy-Nagy, and was eventually appointed workshop assistant. Brandt ended up succeeding Moholy-Nagy as the workshop’s studio director in 1928.[3] Her industrial designs for household objects have been recognized as iconic expressions of the Bauhaus aesthetic.[3] Brandt died on June 18, 1983.

Alma Siedhoff-Buscher was born on January 4, 1899. She attended the Bauhaus from 1922 to 1925, where she studied sculpture and colour theory under Josef Hartwig and Paul Klee. Eventually, Buscher became a successful toy designer.[2] Her most successful works included a line of dolls. Buscher died on September 25, 1944, in a bombing near Frankfurt.

Friedl Dicker was born in Vienna on July 30, 1898. She attended the Bauhaus from 1919 to 1923, where she was involved in the textile design, printmaking, bookbinding and typography workshops. Dicker excelled at the school, as well as in her professional career. She was particularly successful in the fields of painting, jewelry and costume design, as well as interior design.[2] Unfortunately, Dicker died on October 9, 1944, in the Auschwitz concentration camp.

Ilse Fehling was born on April 25, 1896. She began attending the Bauhaus in 1920, where she studied in the sculpting, painting and theatre workshops. Fehling was the only female sculptor at the school. Although she never graduated from the Bauhaus, she had a successful career, as she gained fame from her stage and costume designs for theatres and films.[2] She developed a circular stage design, which was patented in 1922. Fehling died on February 25, 1982.

Marguerite Friedlaender-Wildenhain was born on October 11, 1896. Wildenhain was the first German female pottery master to complete her apprenticeship exam. She established a successful workshop in Amsterdam before leaving for the United States in the 1940s.[2] She then achieved a successful career in California.[2] Wildenhain died on February 24, 1985.

Gertrud Grunow was born on July 8, 1870. She developed theories concerning the relationship between sound, colour and movement. Grunow taught at the Bauhaus from 1919 to 1923, where she taught classes in dance, music and “practical harmonizing.”[2] She was initially employed as an assistant teacher, but eventually became the only female form master at the school. Grunow died on June 11, 1944.

Florence Henri was born on June 28, 1893 in New York City. Initially, Henri attended the Bauhaus, where she studied in the painting workshop. However, she enrolled in a summer photography course that was taught by Moholy-Nagy. By 1928, Henri had ceased painting and left the school. She eventually established a successful photography studio in Paris.[2] In her career, Henri focused mainly on avant-garde photography. She died on July 24, 1982.

Grete Heymann-Loebenstein was born on August 10, 1899. She was a ceramicist who came to the Bauhaus with a prior education in the arts and eventually found professional success.[2] In 1923, she established the Hael Workshops for Art Ceramics, which was a very lucrative business, until its forced closure and sale in 1933. Eventually, she moved to England, where she continued to produce ceramics and paintings, which were praised in post-war London.[2] Heymann died on November 11, 1990.

Lucia Moholy was born on January 18, 1894 in Prague. She attended the Bauhaus, where was trained as a photographer. Moholy captured many images that are essential to the documented history of the Bauhaus.[2] She was also the wife of the master, László Moholy-Nagy.[2] During her career, she and her husband experiment with different processes in the darkroom, like photogram. Moholy died on May 17, 1989.

Lilly Reich was born on June 16, 1885 in Berlin. Reich had prior experience working with embroidery, and designed a variety of clothing and furniture. In 1932, she was asked to teach at the Bauhaus, and direct the interior design workshop. Although the Bauhaus was closed shortly after, Reich continued to have a successful career as an interior designer.[2] She died on December 14, 1947.

Lou Scheper was born on May 15, 1901. Schemer was a skilled painter, who attended the Bauhaus in 1920. She studied mural painting at the school and developed a long career as a painter, children’s book illustrator, and architectural designer.[2] She also continued in the fields of theatre design, illustration and colour theory after she left the school in 1922.[4] Scheper died on April 11, 1976 in Berlin.

Grete Stern was born on May 9, 1904. Stern attended the Bauhaus from 1930 to 1933, where she studied, and later taught, photography. Later in her career, she established a photography practice with fellow Bauhaus photographer, Ellen Rosenberg.[2] Due to the political climate of Nazi Germany, Stern emigrated to Argentina, where she died on December 24, 1999.

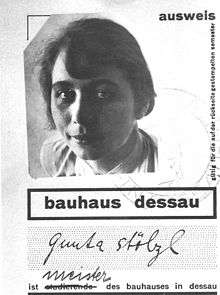

Gunta Stölzl was born on March 5, 1897. She attended the Bauhaus, where she studied weaving and textiles. After graduating from her program, Stölzl returned to the Bauhaus to lead the weaving workshop in 1926. She became the first official female department head, and was the only female master at the school.[2] Stölzl played a crucial role in the development of the school’s weaving workshop, as she focused on designing and weaving abstract textiles for commercial and industrial use.[3]

Controversies

Although the school was praised for its more progressive approach to gender equality, some criticize the schools reputation, claiming that many of its female members went unnoticed both during and after the school’s short existence.[1] Others claim that although the school fronted progressive ideas of gender equality, its administration was rooted in ideals of the past and in misogyny.[4] In the case of Gertrud Arndt, she aspired to study architecture, but was instead redirected into the more domestic or “feminine” subject of weaving, after the administration claimed that there were no available architecture classes for her.[4] Similarly, the school also attempted to redirect Benita Koch-Otte into more domestic subjects, but she persevered with her original studies and became an influential figure in both textile design and art education.[4] However, during her studies, she was often encouraged to give up some of her classes in order to spend more time gardening.[2]

Another source of criticism surrounds the belief that Gropius’s proclamation of gender equality “remained theoretical in the teaching field.”[6] This refers to the gender ratio in the faculty, in which only six of forty-five faculty members were female at the Weimer location.[2] The ratio of female to male faculty members did not improve much as the school progressed. Additionally, the decreasing number of female faculty members paralleled the decrease in female enrolment.[2] The decline in female enrolment also corresponded to Gropius’s alterations to the acceptance policy for women. Because of the initially high influx of female students, Gropius stated that “for the foreseeable future, only women of extraordinary talents would be accepted into the school.”[6] Some argue that this allowed Gropius to accept less female students on the pretence of talent recognition, which also contributed to the decrease in female students.

Furthermore, there was also criticism concerning the apprenticeship programs offered at the school. As previously discussed, the majority of female students at the Bauhaus specialized in weaving. However, the school did not offer apprenticeship certificates in weaving, which meant that it was impossible for women to register their trade with the Chamber of Trade. This prevented them from acquiring master’s diplomas, which placed limits on the future possibilities of their careers.[2]

Exhibitions

In recent years, the Bauhaus Archive in Berlin has tried to make amends to the women of the Bauhaus who felt marginalized at the school, by hosting a series of exhibitions, titled “Female Bauhaus.” Within these exhibitions, the work produced by the female members of the Bauhaus is presented and celebrated.[4] The latest of these shows was devoted to Gertrud Arndt. The exhibition features work from her days as a textile student at the Bauhaus, but also includes the photographic experiments she began at the Bauhaus and continued in her later career.[4] Other female artists that have been featured in the exhibition include fellow textile designer, Benita Koch-Otte, as well as theatre designer, Lou Scheper.[4] The Bauhaus Archive plans to continue with the series and present more shows in the future.

Recent Academic Interest and Publications

In recent years, more attention has been given to the women of the Bauhaus, as academics have continued to recognize their contributions to the visual arts and visual culture. Major newspapers, like The Guardian and The New York Times, have recently published articles concerning the controversies of the Bauhaus, with particular critique of its reputation as an institution that promoted gender equality. Phaidon Press recently released an article which praised the female pioneers of the Bauhaus and included photographs taken by Gertrud Arndt.[7] In 2009, Ulrike Müller published the book, Bauhaus Women: Art, Handcraft, Design, which coincided with the Bauhaus exhibition that was occurring at The Museum of Modern Art. Müller’s book celebrates twenty female members of the Bauhaus, and discusses their lives, works and legacies within the Bauhaus, as well as within the greater context of art history.[6]

References

- 1 2 3 Glancey, Jonathan (2009-11-06). "Haus proud: The women of Bauhaus". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2017-04-04.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Buller, Rachel Epp (2010-01-01). "Review of Bauhaus Women: Art, Handicraft, Design, Ulrike Müller". Woman's Art Journal. 31 (2): 55–57. JSTOR 41331089.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Winton, Author: Alexandra Griffith. "The Bauhaus, 1919–1933 | Essay | Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History | The Metropolitan Museum of Art". The Met’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. Retrieved 2017-04-04.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Rawsthorn, Alice (2013-03-22). "Female Pioneers of the Bauhaus". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2017-04-04.

- 1 2 "Josef and Anni Albers Foundation". www.albersfoundation.org. Retrieved 2017-04-04.

- 1 2 3 Müller, Rachel Epp (2009). Bauhaus Women: Art, Handcraft, Design. Paris: Rizzoli International.

- ↑ "Berlin salutes female pioneers of The Bauhaus | Art | Agenda | Phaidon". Phaidon. Retrieved 2017-04-04.

Bibliography

- Baumhoff, Anja. The Gendered World of the Bauhaus. The Politics of Power at the Weimar Republic's Premier Art Institute, 1919–1931. Peter Lang, Frankfurt, New York, 2001. ISBN 3-631-37945-5

- Cimino, Eric. Student Life at the Bauhaus, 1919-1933. M.A. Thesis, UMass-Boston, 2003, Chapter 6 ("Women at the Bauhaus").