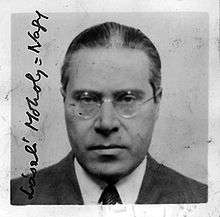

László Moholy-Nagy

| László Moholy-Nagy | |

|---|---|

Declaration of Intention 1938 | |

| Born |

László Weisz July 20, 1895 Bácsborsód, Hungary |

| Died | November 24, 1946 (aged 51) |

| Nationality | Hungarian |

| Known for | painter, photographer |

| Movement | Bauhaus |

| Spouse(s) |

|

László Moholy-Nagy (/məˌhoʊliˈnɒdʒ/; Hungarian: [ˈlaːsloː ˈmohojnɒɟ];[1] born László Weisz; July 20, 1895 – November 24, 1946) was a Hungarian painter and photographer as well as a professor in the Bauhaus school. He was highly influenced by constructivism and a strong advocate of the integration of technology and industry into the arts.

Early life

Moholy-Nagy was born "László Weisz" in Bácsborsód, Hungary to a Jewish family.[2] His cousin was the conductor Sir Georg Solti. He attended Gymnasium in the city of Szeged. He changed his German-Jewish surname to the Magyar surname of his mother's Christian lawyer friend Nagy, who supported the family and helped raise László and his brothers when their Jewish father, Lipót Weisz left the family. Later, he added “Moholy” to his surname, after the name of the town of Mohol (today in Serbia) in which one part of his boyhood was spent, in the family home nearby.

.jpg)

In 1918, he formally converted to the Hungarian Reformed Church; his godfather was his Roman Catholic university friend, the art critic Iván Hevesy. Immediately before and during World War I he studied law in Budapest and served in the war, where he sustained a serious injury. In Budapest, on leave and during convalescence, Moholy-Nagy became involved first with the journal Jelenkor (“The Present Age”), edited by Hevesy, and then with the “Activist” circle around Lajos Kassák’s journal Ma (“Today”). After his discharge from the Austro-Hungarian army in October 1918, he attended the private art school of the Hungarian Fauve artist Róbert Berény. He was a supporter of the Hungarian Soviet Republic, declared early in 1919, though he assumed no official role in it. After the defeat of the Communist regime in August, he withdrew to Szeged. An exhibition of his work was held there, before he left for Vienna around November 1919. He left for Berlin early in 1920.[3][4]

At the Bauhaus

.jpg)

In 1923, Moholy-Nagy took over Johannes Itten's role co-teaching the Bauhaus preliminary course with Josef Albers and also replaced Itten as Head of the Metal Workshop.[5][6] This effectively marked the end of the school’s expressionistic leanings and moved it closer towards its original aims as a school of design and industrial integration.[2] The Bauhaus became known for the versatility of its artists, and Moholy-Nagy was no exception. Throughout his career, he became proficient and innovative in the fields of photography, typography, sculpture, painting, printmaking, and industrial design.

One of his main focuses was photography, in which, from 1922, he was initially guided by the technical expertise of his wife and collaborator Lucia.[7][8][9] In his books Malerei, Photographie, Film of 1925 [10] and The New Vision, from Material to Architecture,[11] of 1932, he coined the term Neues Sehen (New Vision) for his belief that the camera could create a whole new way of seeing the outside world that the human eye could not. This theory encapsulates his approach to his art and teaching. He was the first interwar artist to suggest the use of scientific equipment, the telescope, microscope and radiography in the making of art.[12] With Lucia, he experimented with the photogram; the process of exposing light-sensitive paper with objects laid upon it. His teaching practice covered a diverse range of media, including painting, sculpture, photography, photomontage and metal.[3]

He left the Bauhaus in 1928 and established his own design studio in Berlin.[13] Marianne Brandt took over his role as Head of the Metal Workshop.[6]

Later career

An enduring achievement was Moholy-Nagy's construction of the "Lichtrequisit einer elektrischen Bühne" [Light Prop for an Electric Stage] (completed 1930), a device with moving parts meant to have light projected through it in order to create mobile light reflections and shadows on nearby surfaces.[14][15] Made with the help of the Hungarian architect Istvan Seboek for the Deutscher Werkbund exhibition held in Paris during the summer of 1930, and after his death, it was dubbed the "Light-Space Modulator" and was seen as a pioneer achievement of kinetic sculpture using industrial materials like reflective metals and Plexiglas. Given his intention for it, it might more accurately be seen as one of the earliest examples of Light Art, a form that he continued to develop in the 1940s in the United States, in Space Modulator 1939-1945, Papmac 1943 and B-10 Space Modulator 1942.[16]

.jpg)

Moholy-Nagy was photography editor of the Dutch avant-garde magazine International Revue i 10 from 1927 to 1929. He designed stage sets for successful and controversial operatic and theatrical productions, designed exhibitions and books, created ad campaigns, wrote articles and made films. His studio employed artists and designers such as Istvan Seboek, Gyorgy Kepes and Andor Weininger. After the Nazis came to power in Germany in 1933, and, being a foreign citizen, he was no longer allowed to work. He operated for a time in the Netherlands (doing mostly commercial work) before moving to London in 1935.[2]

In England, Moholy-Nagy formed part of the circle of émigré artists and intellectuals who based themselves in Hampstead. Moholy-Nagy lived in the Isokon building with Walter Gropius for eight months and then settled in Golders Green. Gropius and Moholy-Nagy planned to establish an English version of the Bauhaus but could not secure backing, and then Moholy-Nagy was turned down for a teaching job at the Royal College of Art. Moholy-Nagy made his way in London by taking on various design jobs including Imperial Airways and a shop display for men's underwear. He photographed contemporary architecture for the Architectural Review where the assistant editor was John Betjeman who commissioned Moholy-Nagy to make documentary photographs to illustrate his book An Oxford University Chest. In 1936, he was commissioned by fellow Hungarian film producer Alexander Korda to design special effects for Things to Come. Working at Denham Studios, Moholy-Nagy created kinetic sculptures and abstract light effects, but they were rejected by the film's director. At the invitation of Leslie Martin, he gave a lecture to the architecture school of Hull School of Art.

In the US

In 1937, at the invitation of Walter Paepcke, the Chairman of the Container Corporation of America, Moholy-Nagy moved to Chicago to become the director of the New Bauhaus. The philosophy of the school was basically unchanged from that of the original, and its headquarters was the Prairie Avenue mansion that architect Richard Morris Hunt designed for department store magnate Marshall Field.[17]

Unfortunately, the school lost the financial backing of its supporters after only a single academic year, and it closed in 1938. Moholy-Nagy was also the Art Advisor for the mail-order house of Spiegel in Chicago. Paepcke, however, continued his own support, and in 1939, Moholy-Nagy opened the School of Design. In 1944, this became the Institute of Design. In 1949 the Institute of Design became a part of Illinois Institute of Technology and became the first institution in the United States to offer a PhD in design. Moholy-Nagy authored an account of his efforts to develop the curriculum of the School of Design in his book Vision in Motion.

Death and legacy

Moholy-Nagy died of leukemia in Chicago in 1946. Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design in Budapest is named in his honour. The software company Laszlo Systems (developers of the open source programming language OpenLaszlo) was named in part in honor of Moholy-Nagy. In 1998, he received a Tribute Marker from the City of Chicago. In the autumn of 2003, the Moholy-Nagy Foundation, Inc. was established as a source of information about Moholy-Nagy's life and works.[2] In 2016, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York exhibited a retrospective of Moholy-Nagy's work that included painting, film, photography, and sculpture.[18]

Bibliography

- Moholy-Nagy, László Malerei, Fotografie, Film, Munich: Albert Langen, 1925, 115 pp; 2nd ed., 1927, 140 pp.(German) PDF version: Bauhaus Bücher 8. Malerei, Fotografie, Film (Accessed: 12 January 2017)

- Moholy-Nagy, László; Hoffmann, Daphne M. (translator) (2005) The New Vision: fundamentals of Bauhaus design, painting, sculpture, and architecture. Dover, ISBN 9780486436937.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Forvo.com

- 1 2 3 4 Chilvers, Ian & Glaves-Smith, John eds., Dictionary of Modern and Contemporary Art , Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009. pp. 471-472

- 1 2 Botar, Oliver A.I. (2006). Technical Detours: The Early Moholy-Nagy Reconsidered. New York: Art Gallery of the Graduate Center, the City University of New York. pp. 10–15, 18–20, 163–169. ISBN 978-1599713571.

- ↑ Hacking, Juliet, ed. (2012). Photography: The Whole Story (1st ed.). Munich: Prestel Publishing. pp. 198, 199, 205, 210, 216–221, 334. ISBN 978-3791347349.

- ↑ Bauhaus100. Preliminary course.(Accessed: 7 February 2017)

- 1 2 Bauhaus100. Metal workshop (Accessed: 7 February 2017)

- ↑ Moholy, Lucia; Moholy-Nagy, László, 1895-1946 (1972), Marginalien zu Moholy-Nagy : documentarische ungereimtheiten... = Moholy-Nagy : marginal notes : documentary absurdities, Scherpe

- ↑ Findeli, A. (1987). 'Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, Alchemist of Transparency', in The Structurist, 0(27), 5.

- ↑ Forbes, M. (2016). "WHAT I COULD LOSE": THE FATE OF LUCIA MOHOLY. Michigan Quarterly Review, 55(1), 24-0_7.

- ↑ László Moholy-Nagy 1925. Malerei, Photographie, Film. Munich: Albert Langen

- ↑ Moholy-Nagy, László, (1932) The new vision, from material to architecture. New York: Brewer, Warren & Putnam.

- ↑ Botar, O. (2004). Lszl Moholy-Nagys New Vision and the Aestheticization of Scientific Photography in Weimar Germany. Science in Context, 17(4), 525-556.

- ↑ Bauhaus100. László Moholy-Nagy (Accessed: 7 February 2017)

- ↑ Tate bio Retrieved January 17, 2011

- ↑ Light Art Retrieved January 17, 2011

- ↑ Moholy-Nagy, László |d 1895-1946 & Witkovsky, Matthew S., 1967-, (editor.) & Eliel, Carol S., 1955-, (editor.) & Vail, Karole P. B., (editor.) & Pâenichon, Sylvie, (writer of added text.) et al. (2016). Moholy-Nagy : future present (First edition). Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago.

- ↑ IIT Institute of Design History

- ↑ "Moholy-Nagy: Future Present". 2016-02-02. Retrieved 2016-07-27.

References

- Botar, Oliver A. I. Technical Detours: The Early Moholy-Nagy Reconsidered. New York: Art Gallery of the CUNY Graduate Center, 2006.

- Borchardt-Hume, Achim. Albers and Moholy-Nagy: From the Bauhaus to the New World. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006.

- Chilvers, Ian & Glaves-Smith, John eds., Dictionary of Modern and Contemporary Art, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

- Hight, Eleanor. Picturing Modernity: Moholy-Nagy and Photography in Weimar Germany. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1995.

- Lusk, Irene-Charlotte. Montagen ins Blaue: Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, Fotomontagen und -collagen 1922-1943. Gießen: Anabas, 1980.

- Margolin, Victor. The Struggle for Utopia: Rodchenko, Lissitzky, Moholy-Nagy, 1917-1946. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997.

- Moholy-Nagy, Lázló. Painting Photography Film. 1925. Trans. Janet Seligman. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1973.

- Passuth, Krisztina. Moholy-Nagy. Trans. London: Thames and Hudson, 1985.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to László Moholy-Nagy. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: László Moholy-Nagy |

|

|

- The Moholy-Nagy Foundation

- IIT Institute of Design (Chicago), founded by Moholy-Nagy as 'New Bauhaus in 1937

- Long 2006 article in The Guardian on Moholy-Nagy

- Moholy-Nagy and the Photogram

- Lightplay:Black White Gray

- Art Directors Club biography and portrait

- Moholy-Nagy examples of work for London Transport

- Family house

- https://www.panoramio.com/photo/46242966

- László Moholy-Nagy. Photograms 1922-1943 Exhibition at Fundació Antoni Tàpies