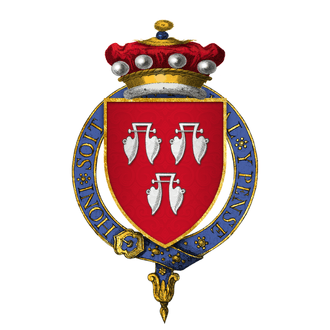

William de Ros, 6th Baron de Ros

William de Ros, sixth Baron Ros (c. 1370–1414) was a medieval English soldier, politician and nobleman. Born to Thomas de Ros, 4th Baron de Ros, William inherited his father's barony, with extensive lands centred on Lincolnshire, in 1394. Soon after he married Margaret, daughter of Baron Fitzalan. The Fitzalan family, like that of de Ros, was an important family in the political community. They were, though, implacably opposed to the King, Richard II, and this may have soured Richard's opinion of the young de Ros.

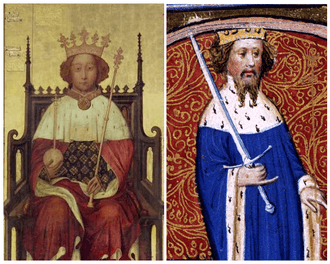

In 1399, King Richard II had confiscated the estates of his cousin, Henry Bolingbroke, Earl of Derby, and exiled him Within a few months, Bolingbroke had invaded England and deposed Richard. Almost immediately de Ros took Bolingbroke's side. Richard's support deserted him, and de Ros was alongside Henry when Richard resigned his throne to the invader. In December that year de Ros voted in the House of Lords in support of the ex-King's imprisonment. De Ros did well under the new Lancastrian regime, and achieved far more than he had ever done under Richard. De Ros became an important aide and councillor to the King and regularly spoke on his behalf in parliament. He also supported Henry in his military campaigns, taking part in the invasion of Scotland in 1400 and then assisting in the suppression of Scrope's rebellion five years later.

De Ros received extensive royal patronage, including lands and grants as well as wardships and their marriages. In return, he not only plied the King with advice, but went on embassies for him and, most practically, loaned Henry large amounts of money, as the King was often in a state of near-penury. De Ros was unable to avoid the tumultuous regional conflicts and feuds that plagued the period. In 1411 he became involved in a land dispute with a powerful Lincolnshire neighbour, and only narrowly escaped an ambush by him. He sought—and received—redress in parliament. Partly because of de Ros' restraint in not seeking severe penalties, de Ros has been described by one twentieth-century historian as being a particularly wise and forbearing figure of the period.

King Henry IV died in 1413. De Roos did not long survive him and played only a minor role in government in his last years. He may well have been out of favour with the new King, Henry V. Henry—as Prince of Wales—had fallen out with his father a few years previously, and de Ros had supported King Henry over his son. William de Ros died in Belvoir Castle on 1 November 1414. His wife survived him by twenty-four years; his son, John was still a minor. John later fought at Agincourt in 1415, but died in France, childless, six years later. The Barony de Ros was then inherited by William's second son, Thomas, who was also to die in military service in France in 1428.

Background and career under Richard II

The exact date of William de Ros' birth is unknown, but in 1394 he was described as being about twenty-three years old, which would place his birth date around 1370.[2] The de Ros' were an important family in the Lincolnshire and southern Yorkshire region,[note 1] and one modern historian lists them as one of the greatest fourteenth-century baronial families never to have received an earldom.[3] De Ros' father was Thomas de Ros, 4th Baron de Ros, who had fought in the Hundred Years War under Edward III, particularly at the Poitiers campaign of 1356. A couple of years before William's birth, the King had instructed his father to dwell, with his army, on his Irish estates "to prevent the loss and destruction of the country".[4] Thomas had married Beatrice, widow of Maurice Fitzgerald, Earl of Desmond; she was the daughter of the first Earl of Stafford. He died at Uffington, Lincolnshire, in June 1384 and his eldest son John—William's elder brother—inherited as fifth Baron de Ros.[5]

As well as Thomas, de Ros had two younger brothers, Robert and Thomas, "of whom", says Charles Ross, "nothing is known".[6] John's career though was to be short. He fought for the new King, Richard II (heir of Edward III, who had died in 1377) on the Scottish border, and joined him on the 1385–86 campaign. He fought in France the following year with the Earl of Arundel. By 1382 he had married Mary, half-sister to the Earl of Northumberland. In the early 1390s he went on pilgrimage to Jerusalem; however, he died at Paphos on the return journey, on 6 August 1393. John and Mary had not produced an heir. Although he had never been expected to succeed to his father's baronage, de Ros was next in line and duly inherited as sixth Baron de Ros. By this point he had already been knighted.[7]

Inheritance and marriage

The de Ros estates were primarily in the east and north of England, and he received livery of them in January 1384. They gave him a sphere of influence based around Lincolnshire, Nottinghamshire, and eastern Yorkshire.[8] At this time, the estate had two dowager baronesses to support,[9] his dead brother's wife, Mary, and his father's widow Beatrice. Mary died within a year of her husband, and her extensive inheritance was divided up among her Percy relations. De Ros received her dower lands, which included the ancient Barony of Helmsley.[10] Beatrice, on the other hand, had already outlived three husbands, and, indeed, was to outlive William. Her dower lands were assigned to her in December 1384, which meant that a large swathe of land was never to come under William's control. These lands were predominantly in the East Riding of Yorkshire.[6]

De Ros received seisin of his estates on 11 February 1394.[11] Soon after, he married Margaret, daughter of John Fitzalan, 1st Baron Arundel and Eleanor Maltravers. She had a 40 mark[12][note 2] annuity from King Richard II, having been in the household of the recently deceased Queen, Anne of Bohemia.[8] Through his wife then, de Ros had a useful connection to the Crown,[13] although he had been a Privy Councillor since at least 1392 by this time.[14] Also useful to William was the fact that his wife's father had also died, and he now had the Earl of Arundel as a brother-in-law. His new connections may account for the royal grants he soon received of Clifford manors in Yorkshire, Derbyshire, and Worcestershire. These had been the dower lands of Euphemia, widow of Robert, Lord Clifford, who had died in November 1393.[13] De Ros attended the King's wedding to the French King's daughter, Isabella of Valois in Calais, in December 1396.[11] The following year de Ros' wife's grandfather died, and she became suo jure Lady Maltravers.[15]

Although de Ros received some royal favour, Charles Ross has suggested that de Ros' may not have been doing as well as he would have expected for a man in his position. Ross suggests that William's Fitzalan connections may have worked against him with the King. Arundel was a staunch political opponent of the King, and so de Ros' having married into this politically unpopular family may account for the few offices the King granted him. This situation would not change, says Ross, until the accession of Arundel's political compadre, Henry Bolingbroke, as King Henry IV in 1399.[13] De Ros appears to have only been appointed to peace commissions on a few occasions, and neither did he sit on many Oyer and Terminer arrays.[13]

Regime change and career under Henry IV

Charles Ross

John of Gaunt died in February 1399.[16] Instead of allowing Bolingbroke to succeed to his father's estates and titles, Richard cancelled the writs of seisin. Instead, King Richard decreed that Bolingbroke would have to request his inheritance at the king's pleasure.[17] Bolingbroke, still in exile, joined with the also-exiled Thomas Arundel the former Archbishop of Canterbury—de Ros' wife's uncle[18]—who had lost his office because of his involvement with the Lords Appellant and been abroad since 1397.[17] With a small group of followers, Bolingbroke landed at Ravenspur in Yorkshire towards the end of June 1399.[19] De Ros, and a large retinue,[20] joined Bolingbroke's army almost immediately, along with most of the northern nobility.[21] Richard was campaigning in Ireland at the time and was unable to defend his throne. Henry initially announced that he intended only to reclaim his rights as Duke of Lancaster, though he quickly gained enough power and support, including that of de Ros, to have himself declared King Henry IV.[22]

De Ros motives for joining Bolingbroke's invasion so swiftly are unknown but, says Given-Wilson, this was no surprise: for most of Henry's new-found allies, "it is only possible to speculate as to their political allegiance".[21] In any case, de Ros need not have had a personal grievance against Richard. He could well have felt generally aggrieved by Richard's poor treatment of Gaunt and Bolingbroke, and de Ros' lack of promotion under Richard.[23] Whatever his motives, both de Ros and his father were Lancastrian rather than Ricardian in their loyalties. His father had been one of John of Gaunt's earliest retainers when Gaunt was earl of Richmond,[24] and de Ros became Gaunt's retainer in the later years of the fourteenth century.[25] Service to the duke involved both accompanying him abroad and travelling on his business, on at least five occasions in the duke's lifetime. For his services, de Ros received annuities of between £40 to £50. He was also one of only two of Gaunt's knight bannerets.[24]

When Bolingbroke returned from exile in June, de Ros was one of the first nobles to join him at Berkeley Castle.[26][11] On 6 September, de Ros witnessed the meeting between Henry and Richard at the Tower of London where the King resigned the throne.[27][11] Bolingbroke's accession as Henry IV saw an uplift in de Ros's fortunes, along with those of the Fitzalans. De Ros now had both strong connections with important figures at court and also a relatively close friendship with the new King himself.[28] In contrast to his treatment by Richard, de Ros' previous loyal service to Henry—and the King's father—earned him significant royal patronage.[27] In the first parliament of the new reign, held at Westminster in October 1399,[29] he was appointed a Trier of Petitions[28] and was one of the lords who voted to imprison Richard[11][30] (who later died in prison by unknown causes).[31] De Ros also sat in Henry's first Royal council in December.[28]

Local administration and political crisis

De Ros' royal service in the shires increased, and he became a leading member of political society in the north midlands and Yorkshire, where he regularly led judicial and administrative commissions.[32] He was also regularly appointed Justice of the peace closer to home, particularly in Leicestershire.[33] His service to the crown was not confined to the regions. In 1401 he directed the King's attempts to increase the royal income. De Ros was Henry's direct negotiator with the House of Commons. His main purpose was to persuade the Commons to agree to a subsidy for the King's intended invasion of Scotland that summer. De Ros and the Commons' representatives met in Westminster's refectory. He emphasised the "favourable consideration" that the Commons would receive from the King, and played on the King's expenses in defending the Welsh and Scottish Marches.[32] Each party was wary of the other: the King careful not to set a precedent, the Commons wary of the House of Lords.[34] Six years later, de Ros performed much the same role again: this time, along with the Duke of York and Archbishop of Canterbury, on a committee hearing the Commons complaints. The result of these discussions was an altercation in which the Commons were "hugely disturbed". This disturbance, says J. H. Wylie, was probably the result of something de Ros said,[35] and may account for the Commons' reluctance to meet him or his committee. De Ros' remit, put simply, was to garner as much in tax in exchange for as few liberties granted, as possible.[36] He was an extremely experienced parliamentarian, and attended most parliaments held between 1394 and 1413.[11]

Almost from the beginning of Henry's reign, the new King faced problems. Most of these stemmed from financial insecurity, and by 1402 his treasury was empty.[34] Around this time,[note 3] de Ros was appointed Lord Treasurer.This, says Ross, indicates the King's increased confidence in de Ros.[41] De Ros occupied this post for the next four years.[28] He was unable to improve Henry's financial situation. At the same time, relations with the Commons worsened. At the 1404 parliament, the speaker, Arnold Savage, robustly confronted the King over his lack of monies which Savage said could be ameliorated immediately by reducing the substantial number of annuities the crown was paying.[note 4] He also condemned am unnamed crown minister for owing royal creditors over £6,000.[34] The House of Commons was, then, not on friendly terms with the King: he responded within the week. Henry despatched de Roos and the Chancellor, Henry Beaufort, to the commons with a detailed exposition of the King's financial requirements. Ian Mortimer notes that "Savage, having attacked royal policy in the King's presence, had no compunction about speaking his mind to the chancellor and treasurer".[42] So Henry's government continued to subsist on poor revenues .[27] As historian Chris Given-Wilson has put it, the treasury became "largely reliant on a diminishing circle of the faithful",[43] which naturally included de Ros. He made loans to the King, and for a while surrendered his councillor's salary.[43]

De Ros also performed military service for the Crown. In 1400, he contracted to bring a fully crewed ship with twenty men at arms and forty archers for Henry's Scottish invasion. Although the campaign fizzled out somewhat ignominiously,[44] de Ros played a personal part in it. Returning to his position as King's councillor, and participated in Henry's Great Council the following year.[45] In 1402, Owain Glyndŵr's Welsh rebellion erupted. The revolt impacted on de Ros personally. His brother-in-law, Reginald, Lord Grey of Ruthin—who had married de Ros' youngest sister, Margaret[41]—was captured and imprisoned by Glyndŵr. Indeed, personal animosity between Gray and Glyndŵr may have been to blame for the outbreak of the rebellion in the first place.[46] The Welsh demanded a 10,000 mark ransom from the King, who agreed to pay. De Ros, probably because of connection to Grey, also agreed to contribute, and he also led the commission which negotiated with Glyndŵr over its payment and his brother-in-law's release.[41] A personal friend of de Ros, fellow Midlands baron Robert, Lord Willoughby, accompanied him.[27]

In 1402 de Ros was elected to the Order of the Garter,[45] and two years later he was granted an annuity of 100 marks per annum as a retainer to Henry IV. In May that year, a rebellion broke out in the north, led by Richard Scrope, Archbishop of Canterbury, and the disaffected Henry Percy, 1st Earl of Northumberland.[47] One of their first acts of rebellion was to kidnap the King's envoy.[48] De Ros was part of an extensive network of northern Lancastrian loyalists that gathered around Ralph Neville, Earl of Westmorland, the King's cousin.[24][note 5] Henry entrusted de Ros to meet up with Westmorland, commander the King's armies in the north. De Ros was probably chosen because of all the King's intimate advisors, de Ros' local knowledge would have been invaluable.[47] He was, after all, "high in the King's confidence and enjoyed especially trusted positions".[49] The mission was a success. De Ros witnessed the Earl of Northumberland's surrender of Berwick Castle to the King[27] and sat on the commission that condemned Scrope to death without trial in early June 1405.[50] When the King arrived in York to oversee the executions of the rebels, de Ros personally brought Henry Percy's bonds to him.[51]

De Ros had been instructed not to engage the rebels without the King authorising it. It is thus difficult to ascertain the precise role that he and Gascoigne played in the rebellion's suppression. Unlike the Earl of Westmorland, for example, "no more is heard of their activities" in the north until after the confrontation at Shipton Moor. De Ros' role may have been to oversee the later judicial commissions over the rebels. He was authorised to pardon those who rejected rebellion and wished to return to the King's grace.[52] The fact that so little of their work is visible may suggest a surreptitiousness to it; possibly, says Chris Given-Wilson, they were little more than spies tailing their prey.[54]

It was only a few years later that the King's health, which had not been strong for some time, broke down for good. At the parliament of 1406, Henry IV agreed that, since it was clear to all that his poor health prevented him from ruling personally, a Grand Council should be established to assist him in governing. De Ros was on the original list presented to parliament of those to be appointed to this council, although how long he served upon it is subject to conjecture. He was certainly attending its meetings in late 1406, as he acted as an unofficial "chaperone" for his successor as Lord Treasurer, Lord Furnivall.[55] De Ros may have still been undertaking this duty in June the following year,[52] when he was regularly witnessing to royal charters. He also continued his role of royal spokesman to the Commons.[56] De Ros probably assisted the Lord Chancellor through what (due to the King's ill-health) became an increasingly difficult period. It is not now certain whether he chose to do so or had been instructed to do so.[57]

Royal favour

King Henry continued to rely on loans to carry out policy, and de Ros' in particular went towards funding the Calais garrison. Unlike many, he was promised repayment. This manifested itself in the royal patronage he continued to receive. By 1409, he had been appointed to the lucrative positions of Constable of Pickering Castle and Master Forester of the same honour. These offices not only strengthened his personal influence in the region, but also allowed him to appoint deputies. This gave de Ros patronage of his own to dispense as he wished. In October that year, de Ros paid £80 for the custody of various Giffard family lands in the south Midlands. Then in December, John Tuchet, Lord Audley died, and de Roos was swiftly granted Audley's lands while his heir was a minor. De Ros also paid £2,000 for the right to sell Audley's heir's marriage. It seems that Audley's estates—from which de Ros was to accrue this amount had been severely overvalued, as the amount he was charged for the young Audley's wedding was quickly halved.[58][note 6] These grants were all on top of his regular conciliar salary of £100 annually,[59] and he held Chingford manor to quarter himself and his men whenever he was in the south on royal business.[11] This was a regular occurrence, as he remained both an active councillor as well as undertaking significant military and diplomatic roles.[60] He was one of Henry's few advisors that, even when the King's council was sitting, remained a close counsellor (he was a regular witness to royal charters, for example, even while not officially on the council).[49]

De Ros remained in the King's favour through the final years of Henry's reign. As a trusted counsellor, in 1410 de Ros took part in what has been described as "a show trial of national importance".[61] The previous year an ecclesiastical court had found John Badby of Evesham[62] guilty of Lollardy. According to custom he had been given a year's grace in which to recant his heresy. This he had not done;[63] indeed, if anything, his opinions were even more entrenched than before. On 1 March 1410, Badby was brought before a convocation at the Friars-Preachers House. De Ros and his fellow barons found Badby guilty, and passed secular judgement on him. He was burnt to death, possibly, according to the sixteenth-century martyrologist, John Foxe, in a barrel,[64] in London's Smithfield.[65][note 7]

Dispute with Robert Tirwhit

After the death of the Earl of Stafford in 1403[68]—whose infant heir had a twenty-year minority[69]—de Ros was now the leading baron in Staffordshire. He was thus responsible for maintaining and upholding the King's peace. In 1411 his intervention averted a tense situation that was likely to erupt into an armed conflict between two of the local gentry, Alexander Mering and John Tuxford.[70] Theirs was only a temporary ceasefire, however, and the following year de Ros sponsored a second arbitration between the two parties, which they promised to abide by on pain of a 500 mark fine.[71] In such efforts, one modern historian has suggested that de Ros' "reputation for fair-mindedness" made him a popular figure for settling gentry disputes.[72] Fifteenth-century England has been a by-word for the kind of pervasive lawlessness that de Ros suppressed. Particularly well known is the frequency with which the baronage and gentry indulged in internecine fighting.[73][note 8] De Ros was no exception to this phenomena and was unable to avoid local strife himself. The same year, he became involved in a dispute with his Lincolnshire neighbour, Sir Robert Tirwhit.[78] Tirwhit was a newly appointed royal justice[79] and a well-known figure in the county. They had fallen out over conflicting claims to common grazing[78] and associated hay-mowing and turf-digging rights in Wrawby.[80] An arbitration took place before Justice William Gascoigne who ordered a Loveday arranged. This occasion was intended to offer both parties the opportunity to demonstrate their support of the arbitration process. The two men were expected to attend with companions or followers while keeping their numbers to a minimum. Tirwhit, however, brought a small army of around 500 men.[78] Justifying the size subsequently, he claimed not to have agreed to the Loveday in the first place.[79] De Ros had kept to the arrangements vis á vis his retinue,[81] bringing with him two kinsmen, Lords Beaumont and de la Warre.[80][note 9]

De Ros and his companions escaped Tirwhit's ambush unharmed.[79] On 4 November 1411, de Ros petitioned parliament for satisfaction, at which he was also appointed a Trier of Petitions. Although, say modern historians, the case was not uncommon in its basic facts, "the personal involvement of a royal justice in such a calculated act of violence, and the status of the protagonists, clearly gave it an interest above the usual".[80] As a result, the case–heard before the Lord Chamberlain and Archbishop of Canterbury–took over three weeks to hear.[80] The Chamberlain and Archbishop requested the attendance of not just de Ros himself, but all the "knyghtes and Esquiers and Yomen that had ledynge of men" for him".[82]They found firmly in de Ros' favour. Tirwhit was bound to gift de Ros a quantity of Gascon wine as well as to provide the food and drink for the next Loveday, where he would also publicly apologise to de Ros. In his apology, Tirwhit acknowledged that a nobleman of de Ros position could also have brought an army and that de Ros had shown forbearance in not doing so. The only responsibility de Ros was given as part of the arbitration award was that at the second Loveday, he would provide the entertainments.[81][note 10]

Later years and death

In these later years, the King's health continued to decline. He improved sufficiently in 1411 to make directions for a new council to be formed of his loyal councillors. This specifically excluded his son, Prince Henry or the latter's associates Henry and Thomas Beaufort.[80] De Ros—the "reliable royalist"—sat on this council for the next fifteen months,[85] along with other "unswervingly loyal" officials such as the Bishops of Durham and Bath and Wells and the Archbishop of York. De Ros and the others now signed off the administrative work that had previously required the King's personal signet seal.[86] Said two of the King's recent biographers, A. L. Brown and Henry Summerson, "at the end of his reign, as at its beginning, Henry placed his trust principally in his Lancastrian retainers".[87]

Henry IV died 20 March 1413, and William de Ros subsequently played no part in government. He probably attended his last council meeting in 1412.[88] Charles Ross posited that he was "no particular favourite" of the new King, Henry V, which Ross attributed to the new King's distrust of his father's loyalists, who, in his eyes, kept him from his rightful position at the head of government through his father's illnesses. Excluded or not, de Ros only survived eighteen months into the new reign. His mother had drawn up her will in January 1414,[89] of which he was an executor.[2] Early the same year, de Ros sat on a final anti-Lollard commission,[note 11] A second task included investigating the murder of an M.P. in the Midlands.[93]

De Ros died in Belvoir Castle on 1 November 1414. He had drawn up his will two years previously, and had added a codicil to it in February 1414.[94][note 12] He was, after all, a wealthy man, having one of the highest disposable incomes in Yorkshire at the time of his death.[95][note 13]

At least three of William de Ros' children fought in the later period of the Hundred Years War. His heir, John, had been born in 1397, so was still legally a minor when his father died. The Earl of Dorset, cousin to the King, received custody of the de Ros estates.[15] Although still a minor, John travelled to France with the new King in 1415 and fought at the Battle of Agincourt, aged seventeen or eighteen.[97] He took part in the siege of Orléans, but died in 1421 at the Battle of Baugé, alongside the King's brother, Thomas, Duke of Clarence and Sir Gilbert Umfraville.[98] William de Ros' second son Thomas was only fourteen on John's death,[99] but fought for Thomas, Earl of Salisbury at the Siege of Orléans, although he died after a military skirmish outside Paris two years later.[100] Thomas's heir, also Thomas, inherited the barony, and played an important role in the Wars of the Roses, where he fought for the Lancastrian King, Henry VI, only to be beheaded after being defeated by the Yorkists at the Battle of Hedgeley Moor in 1464.[101] De Ros' wife, Margaret Fitzalan, survived him, living until 1438. She had received her dower by February 1415 and, on the marriage of Henry V to Katherine of Valois in 1420, Margaret entered the new Queen's service as a lady-in-waiting. Margaret attended Katherine's coronation and travelled with her to see Henry in France two years later.[15]

Family and bequests

By his wife Margaret Fitzalan, William de Ros had four sons, and another illegitimate.[103] They were John, Thomas, Robert and Richard. They had four daughters, Beatrice, Alice, Margaret and Elizabeth.[104] De Ros's heir, John inherited not just the lordship and patrimony, but all William's armour and a sword made of gold. His second son Robert—whom Ross describes as being "evidently his favourite"—also inherited a quantity of land.[105] De Ros had carved this provision out for Robert from the elder son's patrimony. This decision has been described by G. L. Harriss as "overrid[ing] both family duty and convention".[103] The younger three sons, Thomas, Robert, and Richard received a third of de Ros's goods between them. Thomas, as was often the case for a younger son, was intended for an ecclesiastical career. Margaret was likewise not forgotten and received another third of his goods. Even his illegitimate son, John, received £40 towards his upkeep. Loyal retainers received benefices, and de Ros' "humbler dependents"—for instance, the poor on his Lincolnshire estates—received often massive sums.[note 14] His executors received £20 each for their services (one of whom was his heir, John).[94] He was buried in Belvoir Priory, and an alabaster effigy of him was erected in St Mary the Virgin's Church, Bottesford,[106] which church has de Ros family armigers throughout. His effigy was situated to the side of the altar. Seven years later, that of his son John was placed on the other.[107] William de Ros left £400 to pay ten chaplains for eight years for the education of his sons.[108]

In literature

William de Ros appears as a character in Richard II by William Shakespeare, as Lord Ross.[109] The character performs something of a double-act with Lord Willoughby in their (ultimately successful) attempts to persuade the Earl of Northumberland to revolt against Richard.[110] In the course of doing so, they provide the audience with a catalogue of Richard's misdeeds and a re-telling of his poor governance.[111] Ross is portrayed as being an overt follower of Henry Bolingbroke from the beginning. Described by Shakespeare, vice Holinshed, as being "fiery-red with haste", Ross / de Ros joins Bolingbroke at Berkeley, Gloucestershire.[112]

Notes

- ↑ The family name was also variously spelt by contemporaries as Roos, Ross, and Rous, among other variants.[1] Modern historians thus also choose different spellings.

- ↑ A medieval English mark was a unit of currency equivalent to two-thirds of a pound.

- ↑ There is some uncertainty as to when the appointment occurred and when it ended. William Dugdale, in his Baronage,[37] and F. M. Powicke and E. B. Fryde [38] all suggest 1403 to 1406, while J. H. Wylie[39] believed it had started by 1401 and had ended by 1404. Anthony Steele, on the other hand, dates de Ros' appointment quite precisely to between 14 July and 16 September 1403, but also says that Furnival replaced him in December the next December.[40]

- ↑ Henry had by now paid the enormous sum of nearly £5,000 to those of his followers who had accompannied him on his inavsion up to the October 1399 parliament: they included two earls, three barns, and 44 others, including knights and squires.[20]

- ↑ Indeed, at this time, relations between Westmorland and Henry IV were so close that the King regularly referred to the earl in official documents as his brother

- ↑ It should, of course, be noted that he also lost grants through natural reasons; for instance, although he had enjoyed custody of various Clifford family estates since 1394 (his sister had married Thomas de Clifford, 6th Baron de Clifford, sometime around 1379), and their son came of age around 1411.[59]

- ↑ Lollardy was a late fourteenth-century religious reform movement, which by the fifteenth century was deemed outright heresy.[66] It lasted for such a long time because it did have a genuine appeal;[67] King Henry IV, however, had a personal antipathy for the sect. In 1401, he signed into law De heretico comburendo ("On the Burning of Heretics"), which for the first time in English history provided a statutory instrument for the burning of those found guilty of heresy before church courts. This, suggests Richard Rex, was "in order to bolster his own feeble legitimacy by support for orthodoxy".[66]

- ↑ For example, the second quarter of the fifteenth century saw a long-running feud between different branches of the Neville family in the north.[74] By the 1450s, such feuds were legion: between the Courtenay and Bonville families in the southwest;[75] between the two powerful northern dynasties, the Nevilles (again) and the Percies;[76]; and between Ralph, Lord Cromwell and William, Lord Tailboys in the Midlands.[77]

- ↑ De Ros' petition to parliament, which lays out Gascoigne's decision, reads less specifically than de Ros suggested: "And the said William Gascoigne decided that the said William de Roos should come there with the husbands of two of his kinsfolk, or other friends, in a peaceful manner, with as many men as customarily rode with them. And that the said Robert should come peacefully with two of his kinsmen or friends, with as many men as is fitting for their estate and position".[80]

- ↑ Tirwhit, it has been suggested, considering the number of public offices he had to lose—and the outcry that had erupted from his "grossest turbulence and breach of the peace"[83]—"doubtless considered himself fortunate to escape" so lightly. In the event, Tirwhit retained his office on the Lincolnshire King's Bench for the rest of his life—another quarter of a century.[80]

- ↑ These commissions were in response to the Oldcastle Revolt of January 1414: "chief commissioner to hear and determine as to rebellions, treasons, &co. in Middlesex, and in Nottinghamshire and Derby committed by the King’s subjects commonly called Lollards".[90] The commission was composed of six men, the three most important of whom were de Ros, Henry Scrope, and the Mayor of London, William Cromer.[91] Maurice Keen described the rebellion itself as a "complete fiasco".[92]

- ↑ De Ros' will has been printed in full in F. M. Powicke's The Register of Archbishop Chichele II, 22–27. It is extremely detailed. De Ros went as far as specifying three separate burial sites depending on where he died, with the proviso that where ever he didn't die should not lose out on a handsome request each. It also makes full provision for his sons, distributing estates, goods, and annuities between them.[94]

- ↑ It has been estimated that his income was matched only by three of his fellow Yorkshire-based barons. They were of Neville, Furnivall, and Scrope of Bolton.[96]

- ↑ His poor, his servants, and his tenants all received £100 each between them.[102]

References

- 1 2 Newton 1846, p. 210.

- 1 2 Ross 1950, p. 111.

- ↑ Given-Wilson 1987, p. 64.

- ↑ Cokayne 1910, p. 101.

- ↑ Cokayne 1910, pp. 101–102.

- 1 2 Ross 1950, p. 107.

- ↑ Cokayne 1910, pp. 100–101.

- 1 2 Ross 1950, p. 112.

- ↑ Ross 1950, p. 105.

- ↑ Ross 1950, pp. 105–106.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Cokayne 1910, p. 102.

- ↑ Davis 2012, p. 17.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ross 1950, p. 113.

- ↑ Baldwin 1913, p. 492.

- 1 2 3 Cokayne 1910, p. 103.

- ↑ Barr 1994, p. 146.

- 1 2 Bevan 1994, p. 51.

- ↑ Cokayne 1910, p. 100.

- ↑ Saul 1997, p. 408.

- 1 2 Given-Wilson 1993, p. 35.

- 1 2 Given-Wilson 1999, p. 114.

- ↑ Bevan 1994, p. 66.

- ↑ Arvanigian 2003, p. 131.

- 1 2 3 Arvanigian 2003, p. 119.

- ↑ Given-Wilson 1987, p. 173.

- ↑ Given-Wilson 1999, p. 99.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Arvanigian 2003, p. 133.

- 1 2 3 4 Ross 1950, p. 114.

- ↑ Given-Wilson et al. 2005a.

- ↑ Ross 1950, p. 115.

- ↑ Saul 1997, p. 425.

- 1 2 Wylie 1884, pp. 402–406.

- ↑ Walker 2006, p. 86.

- 1 2 3 Mortimer 2007, p. 254.

- ↑ Wylie 1896, p. 120.

- ↑ Bruce 1998, p. 254.

- ↑ Dugdale 1675, p. 551.

- ↑ Powicke & Fryde 1961, p. 84.

- ↑ Wylie 1894, p. 112.

- ↑ Steel 1954, p. 419.

- 1 2 3 Ross 1950, p. 116.

- ↑ Mortimer 2007, p. 280.

- 1 2 Given-Wilson 2016, p. 287 +n.

- ↑ Brown 1974, p. 40.

- 1 2 Ross 1950, pp. 115–116.

- ↑ Smith 2004.

- 1 2 Given-Wilson 2016, p. 267+n.

- ↑ Wylie 1894, p. 178.

- 1 2 Dodd 2003, p. 104.

- ↑ Wylie 1894, pp. 231–232.

- ↑ Wylie 1894, p. 175.

- 1 2 3 Ross 1950, p. 117.

- ↑ Nicolas 1834, p. 262.

- ↑ Given-Wilson 2016, p. 413.

- ↑ Given-Wilson 2016, p. 299+n.

- ↑ Biggs 2003, p. 191.

- ↑ McNiven 1987, p. 128.

- ↑ Ross 1950, p. 119.

- 1 2 Ross 1950, p. 120.

- ↑ Given-Wilson 2016, pp. 440–441.

- ↑ McNiven 2004.

- ↑ Bevan 1994, p. 144.

- ↑ Bevan 1994, pp. 144–145.

- ↑ Bevan 1994, p. 145.

- ↑ McNiven 1987, pp. 202–203.

- 1 2 Rex 2002, p. 83.

- ↑ Keen 1973, p. 246.

- ↑ Bevan 1994, p. 105.

- ↑ Harriss 2005, p. 524.

- ↑ Payling 1987, p. 142.

- ↑ Payling 1987, p. 148.

- ↑ Payling 1987, p. 150.

- ↑ Kaminsky 2002, p. 55.

- ↑ Petre 1981, pp. 418–435.

- ↑ Storey 1986, pp. 84–92.

- ↑ Griffiths 1968, pp. 589–632.

- ↑ Freidrichs 1988, pp. 207–227.

- 1 2 3 Ross 1950, pp. 121–123.

- 1 2 3 Wylie 1894, pp. 189–190.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Given-Wilson et al. 2005b.

- 1 2 Ross 1950, p. 122.

- ↑ Hilton 1976, p. 250.

- ↑ Fortescue 1885, p. 22.

- ↑ Ross 1950, p. 121.

- ↑ Given-Wilson 2016, p. 496.

- ↑ Wylie 1894, pp. 427–428.

- ↑ Brown & Summerson 2004.

- ↑ Cokayne 1910, p. 102 n..

- ↑ Ross 1950, p. 110.

- ↑ Cokayne 1910, p. 103; P. R. O. 1910, p. 162.

- ↑ Waugh 1905, p. 643 n.25.

- ↑ Keen 1973, p. 245.

- ↑ Jacob 1993, p. 455 +n..

- 1 2 3 Ross 1950, pp. 124–125.

- ↑ Given-Wilson 1987, p. 157.

- ↑ Given-Wilson 1987, p. 156.

- ↑ Barker 2005, p. 227.

- ↑ Burne 1999, p. 157.

- ↑ Milner 2006, p. 490.

- ↑ Burne 1999, p. 228.

- ↑ Gillingham 1981, pp. 151–152.

- 1 2 Ross 1950, p. 125.

- 1 2 Harriss 2005, p. 104.

- ↑ Eller 1841, p. 26.

- ↑ Ross 1950, p. 124.

- ↑ Wylie 1894, p. 180.

- ↑ Historic England 2018.

- ↑ Wylie 1894, p. 119 n..

- ↑ Shakespeare 2002, p. 177.

- ↑ McLeish 1992, p. 246; McLeish 1992, p. 166.

- ↑ Irish 2013, p. 147.

- ↑ Griffin-Stokes 1924, p. 283.

Bibliography

- Arvanigian, M. (2003). "Henry IV, the Northern Nobility and the Consolidation of the Regime". In Biggs, D.; Dodd, G. Henry IV: The Establishment of the Regime, 1399-1406. Cambridge: The Boydell Press. pp. 185–206. ISBN 9781903153123.

- Baldwin, J. F. (1913). The King's Council in England During the Middle Ages. Oxford: Clarendon. OCLC 837474744.

- Barker, J. (2005). Agincourt: The King, the Campaign, the Battle. St Ives: Little, Brown. ISBN 978-0-7481-2219-6.

- Barr, H. (1994). Signes and Sothe: Language in the Piers Plowman Tradition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-85991-419-2.

- Bevan, B. (1994). Henry IV. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0312116972.

- Biggs, D. (2003). "The Politics of Health: Henry IV and the Long Parliament of 1406". In Biggs, D.; Dodd, G. Henry IV: The Establishment of the Regime, 1399-1406. Cambridge: The Boydell Press. pp. 95–116. ISBN 9781903153123.

- Brown, A. L. (1974). "The English Campaign in Scotland". In Hearder, H.; Lyon, H. R. British Government and Administration: Studies Presented to S. B. Chrimes. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. pp. 40–54. ISBN 0-7083-0538-5.

- Brown, A. L.; Summerson, H. (2004). "Henry IV [known as Henry Bolingbroke] (1367–1413)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 18 May 2018. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- Bruce, M. L. (1998). The Usurper King: Henry of Bolingbroke, 1366-99 (2nd ed.). Guildford: The Rubicon Press. ISBN 978-0948695629.

- Burne, A. H. (1999). The Agincourt War: A Military History of the Hundred Years War from 1369 to 1453. Chatham: Wordsworth Editions. ISBN 978-1-4738-3901-4.

- Cokayne, G. E. (1910). Gibbs, V.; White, G. H., eds. The Complete Peerage of England, Scotland, Ireland, Great Britain and the United Kingdom. XI: Rikerton÷Sisonby. London: The St. Catherine's Press. OCLC 861236878.

- Davis, J. (2012). Medieval Market Morality: Life, Law and Ethics in the English Marketplace, 1200–1500. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-50281-8.

- Dodd, G. (2003). "Henry IV's Council, 1399-1405". In Biggs, D.; Dodd, G. Henry IV: The Establishment of the Regime, 1399-1406. Cambridge: The Boydell Press. pp. 95–116. ISBN 9781903153123.

- Dugdale, W. (1675). The baronage of England, or, An historical account of the lives and most memorable actions of our English nobility in the Saxons time to the Norman conquest, and from thence, of those who had their rise before the end of King Henry the Third's reign deduced from publick records, antient historians, and other authorities. I (1st ed.). London: Abel Roper, Iohn Martin, and Henry Herringman. OCLC 222916155.

- Eller, I. (1841). The history of Belvoir castle, from the Norman conquest to the nineteenth century. London: R. Tyas. OCLC 23603815.

- Fortescue, J. (1885). Plummer, C., ed. The Governance of England, Otherwise Called, The Difference Between an Absolute and a Limited Monarchy (1st ed.). London: Oxford University Press. OCLC 60725083.

- Freidrichs, R.L. (1988). "Ralph, Lord Cromwell and the Politics of Fifteenth-Century England". Nottingham Medieval Studies. 32: 207–227. OCLC 941877294.

- Gillingham, J. (1981). The Wars of the Roses: Peace and Conflict in 15th Century England. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-1-84212-274-7.

- Given-Wilson, C. (1987). The English Nobility in the Late Middle Ages: The Fourteenth-century Political Community. London: Routledge. ISBN 0415148839.

- Given-Wilson, C., ed. (1993). Chronicles of the Revolution, 1397-1400: The Reign of Richard II. Manchester: Manchester University Press. pp. Manchester Medieval studies. ISBN 978-0-71903-527-2.

- Given-Wilson, G. (1999). "Richard II and the Higher Nobility". In Goodman, A.; Gillespie, J. L. Richard Il: The Art of Kingship. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 107–128. ISBN 978-0199262205.

- Given-Wilson, C. (2016). Henry IV. Padstow: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300154191.

- Given-Wilson, C.; Brand, P.; Phillips, S.; Ormrod, M.; Martin, G.; Curry, A.; Horrox, R., eds. (2005a). "'Henry IV: October 1399'". British History Online. Parliament Rolls of Medieval England. Woodbridge. Archived from the original on 17 May 2018. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- Given-Wilson, C.; Brand, P.; Phillips, S.; Ormrod, M.; Martin, G.; Curry, A.; Horrox, R., eds. (2005b). "'Henry IV: November 1411'". British History Online. Parliament Rolls of Medieval England. Woodbridge. Archived from the original on 18 May 2018. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- Griffin-Stokes, F. (1924). A Dictionary of the Characters and Proper Names in the Works of Shakespeare: With Notes on the Sources and Dates of the Plays and Poems. New York: Peter Smith. OCLC 740891857.

- Griffiths, R.A. (1968). "Local Rivalries and National Politics-The Percies, the Nevilles, and the Duke of Exeter, 1452-55". Speculum. 43. OCLC 709976972.

- Harriss, G.L. (2005). Shaping the Nation: England 1360–1461. Oxford: Clarenden Press. ISBN 978-0198228165.

- Hilton, R. H. (1976). Peasants Knights Heretics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-52121-276-2.

- Historic England (2018). "Church of St Mary, Church st, Bottesford: List entry Number: 1075095". Historic England. Archived from the original on 17 May 2018. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- Irish, B. J. (2013). "Writing Woodstock: The Prehistory of Richard II and Shakespeare's Dramatic Method". Renaissance Drama. 41: 131–149. OCLC 1033809224.

- Jacob, E. F. (1993). The Fifteenth Century 1399–1485. (Oxford History of England) (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0192852868.

- Kaminsky, H. (2002). "The Noble Feud in the Later Middle Ages". Past and Present. 177: 55. OCLC 664602455.

- Keen, M. H. (1973). England in the Later Middle Ages (1st ed.). London: Methuen. ISBN 978-0-416-75990-7.

- McLeish, K. (1992). Shakespeare's Characters: A Players Press Guide : Who's who of Shakespeare. London: Players Press. ISBN 978-0-88734-608-8.

- McNiven, P. (1987). Heresy and Politics in the Reign of Henry IV: The Burning of John Badby. Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 978-0851154671.

- McNiven, P. (2004). "Badby, John (d. 1410), Lollard heretic". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 17 May 2018. Retrieved 17 May 2018. (Subscription required (help)).

- Milner, J. D. (2006). "The Battle of Baugé, March 1421: Impact and Memory". History. 91: 484–507. OCLC 1033072577.

- Mortimer, I. (2007). The Fears of Henry IV: The Life of England's Self-Made King. London: Vintage. ISBN 978-1-84413-529-5.

- Newton, W. (1846). A Display of Heraldry. London: W. Pickering. OCLC 930523423.

- Nicolas, H., ed. (1834). Proceedings and Ordinances of the Privy Council of England: 10 Richard II. MCCCLXXXVI to 11 Henry IV. MCCCCX. I (1st ed.). London: Public Record Office. OCLC 165147667.

- P. R. O. (1910). Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1413–1418 (1st ed.). London: H. M. S. O. OCLC 977899061.

- Payling, S. J. (1987). "Law and Arbitration in Nottinghamshire, 1399–1461". In Rosenthal J. T.Richmond C. People, Politics, and Community in the Later Middle Ages. Gloucester: Alan Sutton. pp. 140–160. ISBN 978-0-31201-220-5.

- Petre, J. (1981). "The Nevilles of Brancepeth and Raby 1425-1499. Part I, 1425-1469: Neville vs Neville". The Ricardian. 6: 418–435. OCLC 1006085142.

- Powicke, F. M.; Fryde, F. B. (1961). Handbook of British chronology. London: Offices of the Royal Historical Society. OCLC 916039036.

- Rex, R. (2002). The Lollards. Social History in Perspective. Basingstoke: Macmillan International. ISBN 978-0-230-21269-5.

- Ross, C. D. (1950). The Yorkshire Baronage, 1399-1436 (Dphil thesis). Oxford.

- Saul, N. (1997). Richard II. Bury St Edmunds: Yale University Press. ISBN 0300070039.

- Shakespeare, W. (2002). Forker, C.R., ed. King Richard the Second. Third. London: Arden Shaekspeare. ISBN 978-1903436332.

- Smith, Llinos (2004). "Glyn Dŵr [Glyndŵr], Owain [Owain ap Gruffudd Fychan, Owen Glendower] (c. 1359–c. 1416)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 17 May 2018. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- Steel, A. (1954). The Receipt of the Exchequer, 1377-1485. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. OCLC 459676108.

- Storey, R.L. (1986). The End of the House of Lancaster (2nd ed.). Gloucester: Alan Sutton. ISBN 0750921994.

- Walker, S. (2006). Political Culture in Late Medieval England. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-71906-826-3.

- Waugh, W. T. (1905). "Sir John Oldcastle". The English Historical Review. 20: 434–456. OCLC 754650998.

- Wylie, J.H. (1884). History of England under Henry the Fourth. I. London: Longmans, Green. hdl:2027/yale.39002015298368. OCLC 923542025.

- Wylie, J.H. (1894). History of England under Henry the Fourth. II. London: Longmans, Green. hdl:2027/coo1.ark:/13960/t6n02bt00. OCLC 312686098.

- Wylie, J.H. (1896). History of England under Henry the Fourth. III. London: Longmans, Green. hdl:2027/coo1.ark:/13960/t42r51t5k. OCLC 923542042.

| Preceded by Guy Mone |

Lord High Treasurer 1403–1404 |

Succeeded by Thomas Nevill, 5th Baron Furnivall |

| Peerage of England | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by John de Ros |

Baron de Ros 1394–1414 |

Succeeded by John de Ros |