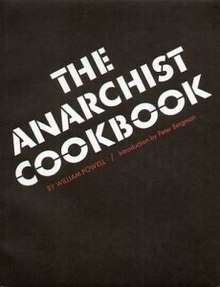

The Anarchist Cookbook

| |

| Author | William Powell |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Publisher | Lyle Stuart |

Publication date | 1971 |

The Anarchist Cookbook, first published in 1971,[1] is a book that contains instructions for the manufacture of explosives, rudimentary telecommunications phreaking devices, and related weapons, as well as instructions for home manufacturing of illicit drugs, including LSD. It was written by William Powell at the apex of the counterculture era to protest against United States involvement in the Vietnam War.[2] Powell converted to Anglicanism in 1976, and later attempted to have the book removed from circulation, but the copyright belonged to the publisher who continued circulation until the company was acquired in 1991. Its legality has been questioned in several jurisdictions.

History

Creation

The Anarchist Cookbook was written by William Powell as a teenager and first published in 1971 at the apex of the counterculture era to protest against United States involvement in the Vietnam War.[2][1]

Author remorse

After writing the book as a teenager, Powell converted to Anglicanism in 1976, and later attempted to have the book removed from circulation.[3][2] He was powerless to stop publication because the copyright had been issued to the original publisher (Lyle Stuart), and subsequent publishers that purchased the rights have kept the title in print. Powell publicly renounced his book in both a 2000 statement for the Amazon bookstore[4] and a 2013 piece calling for the book to "quickly and quietly go out of print".[5] William Powell died of cardiac arrest on 11 July 2016.[6]

Publication status

The copyright of the book never belonged to its author, but to its publisher Lyle Stuart.[2] Stuart kept publishing the book until the company was bought in 1991 by Steven Schragis, who decided to drop it. Out of the 2,000 books published by the company, it was the only one that Schragis decided to stop publishing. Schragis said publishers have a responsibility to the public, and the book had no positive social purpose that could justify keeping it in print.[7] The copyright was bought in 2002 by Delta Press (aka Ozark Press[8][9]) an Arkansas-based publisher that specializes in controversial books, where the title is their "most-asked-for volume".[10]

Reception

At the time of its publication, one Federal Bureau of Investigation memo described The Anarchist Cookbook as "one of the crudest, low-brow, paranoiac writing efforts ever attempted".[11]

In 2010, the FBI released the bulk of its investigative file on The Anarchist Cookbook.[12][13]

Anarchism

Advocates of anarchism dispute the association of the book with anarchist political philosophy. The anarchist collective CrimethInc., which published the book Recipes for Disaster: An Anarchist Cookbook in response, denounces the earlier book, saying it was "not composed or released by anarchists, not derived from anarchist practice, not intended to promote freedom and autonomy or challenge repressive power – and was barely a cookbook, as most of the recipes in it are notoriously unreliable".[14]

Online presence

Much of the publication was copied and made available as text documents online[15] through Usenet and FTP sites hosted in academic institutions in the early 1990s, and has been made available via web browsers from their inception in the mid-1990s to the present day. The name varies slightly from Anarchist Cookbook to Anarchy Cookbook and the topics have expanded vastly in the intervening decades. Many of the articles were attributed to an anonymous author called The Jolly Roger.

In 2001, British businessman Terrance Brown created the now defunct website anarchist-cookbook.com and sold copies of his derivative work, titled Anarchist Cookbook 2000.

Knowledge of the book, or copied online publications of it, increased along with the increase in public access to the Internet throughout the mid-1990s. Newspapers ran stories about how easy the text was to get hold of, and the influence it may have had with terrorists, criminals and experimental teenagers.[15]

Legality

The book was refused classification by the Office of Film and Literature Classification upon release, thus making the book banned in Australia. It was classified RC again on 31 October 2016.[16][17]

In 2007, a 17-year-old was arrested in the United Kingdom and faced charges under anti-terrorism law in the UK for possession of this book, among other things.[18] He was cleared of all charges in October 2008, after arguing that he was a prankster who just wanted to research fireworks and smoke bombs.[19]

In County Durham, UK in 2010, Ian Davison and his son were imprisoned under anti-terrorism laws for the manufacturing of ricin, and their possession of The Anarchist Cookbook, along with its availability, was noted by the authorities.[20]

In 2013, renewed calls were made in the United States to ban this book, citing links to a school shooting in Colorado, USA by Karl Pierson.[10]

In 2017, a 27-year-old was prosecuted in UK solely for the possession of the book. He was found not guilty.[21]

Despite this the book is readily available from major online retailers e.g. Amazon[22] and Barnes & Noble.[23]

Legacy

The book was a frequent target for challenges to its content throughout the 1990s.[24] It served as a central element of the 2002 romantic comedy The Anarchist Cookbook.[25] Repercussions from the book's publication, and the author's subsequent disavowal of its content, were the subject of the 2016 documentary film American Anarchist by Charlie Siskel. In the film, William Powell explains in depth his thoughts on the book, and the consequences it had in his life.[26]

See also

References

- 1 2 "The Anarchist Cookbook LoC entry". Retrieved May 15, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 Mieszkowski, Katharine (September 18, 2000). "Blowing up The Anarchist Cookbook". Salon.com. Retrieved 2 July 2016.

- ↑ Saner, Emine. "Why the author of The Anarchist Cookbook wants it taken off the shelves". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- ↑ William, Powell. ""From the Author" statement". Retrieved 30 July 2017.

- ↑ "I wrote the Anarchist Cookbook in 1969. Now I see its premise as flawed". The Guardian. 19 December 2013. Retrieved 19 December 2013.

- ↑ Richard Sandomir (29 March 2017). "'William Powell, Anarchist Cookbook writer, Dies at 66'". The New York Times. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- ↑ Smith, Dinitia (January 6, 1992). "The Happy Hawker: Tyro Publisher Steven Schragis's Genius for Promoting Schlock". New York Magazine. 25 (1). p. 46. ISSN 0028-7369.

- ↑ Arkansas publisher keeping controversial book on the shelves (2015 April 21)

- ↑ The Anarchist Cookbook Turns 40 (2011 January 31)

- 1 2 Dokoupil, Tony (17 December 2013). "After latest shooting, murder manual author calls for book to be taken 'immediately' out of print". NBC News. Retrieved 19 December 2013.

- ↑ Walker, Jesse (2011-02-16) The FBI on The Anarchist Cookbook, Reason

- ↑ FBI Files on the Anarchist Cookbook Retrieved on February 14, 2011

- ↑ Mirror of "FBI Files on the Anarchist Cookbook" Archived July 8, 2015, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on July 24, 2013

- ↑ The Guardian, September 2004, as quoted at CWC Books : Recipes For Disaster Retrieved on November 22, 2007

- 1 2 Sankin, Aaron (2015-03-22). "The Kernel". Kernelmag.dailydot.com. Retrieved 2018-02-06.

- ↑ "Banned Books in Australia: A Selection". University of Melbourne. Archived from the original on February 3, 2016.

- ↑ "THE ANARCHIST COOKBOOK". Classification Board. Australian Government. October 31, 2016. Retrieved November 5, 2016.

- ↑ "Boy in court on terror charges". BBC News. 2007-10-05.

- ↑ "Teenage bomb plot accused cleared". BBC News. 2008-10-23.

- ↑ "County Durham terror plot father and son are jailed". BBC News. 2010-05-14.

- ↑ Gallagher, Ryan (October 28, 2017). "How the U.K. Prosecuted a Student on Terrorism Charges for Downloading a Book".

- ↑ "The Anarchist Cookbook: William Powell: 9781684111374: Amazon.com: Books". Amazon.com. Retrieved 2018-02-06.

- ↑ Noble, Barnes &. "The Anarchist Cookbook". Barnes & Noble.

- ↑ American Library Association: 100 most frequently challenged books: 1990–1999

- ↑ "The Anarchist Cookbook Reviews". Metacritic. Retrieved 2018-02-06.

- ↑ "American Anarchist Reviews". Metacritic. Retrieved 2018-02-06.

Further reading

- Larabee, Ann (2015). The Wrong Hands: Popular Weapons Manuals and Their Historic Challenges to a Democratic Society. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-020117-3. OCLC 927145132.

- Thompson, Gabriel (February 27, 2015). "Burn After Reading". Harper's. Browsings (blog). Retrieved March 3, 2015.