William G. Enloe

| William G. Enloe | |

|---|---|

| |

| Mayor of Raleigh, North Carolina | |

|

In office July 1, 1957 – July 1, 1963 | |

| Preceded by | Fred B. Wheeler |

| Succeeded by | James W. Reid |

| Member of the Raleigh City Council | |

|

In office 1953–1957 | |

|

In office 1971 – November 22, 1972 | |

| Preceded by | Thomas W. Bradshaw |

| Succeeded by | Edith Reid |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

June 15, 1902 Rock Hill, South Carolina, United States |

| Died |

November 22, 1972 (aged 70) Raleigh, North Carolina |

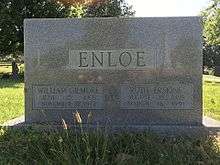

| Resting place | Historic Oakwood Cemetery |

| Spouse(s) | Ruth Erskine |

| Children | 2 |

William Gilmore "Bill" Enloe (June 15, 1902 – November 22, 1972) was an American businessman and politician who served as the Mayor of Raleigh, North Carolina from 1957 to 1963. Enloe was born in South Carolina and sold popcorn before moving to North Carolina and taking up work with North Carolina Theatres, Inc. In 1953 he was elected to the City Council of Raleigh. Four years later he was elected Mayor. During his tenure the American South was permeated by civil unrest due to racial segregation. Considered a moderate on civil rights, Enloe criticized black demonstrators and resisted efforts to integrate the theaters he managed, but he eventually compromised and appointed a committee to oversee the desegregation of Raleigh businesses. He left office in 1963, but returned to the city council in 1971. He died the following year. William G. Enloe High School in Raleigh was named in his honor.

Biography

William Gilmore Enloe was born on June 15, 1902 in Rock Hill, South Carolina, United States.[1] He started working by selling popcorn at the Bijou Theatre in Greenville[2] when he was 12 years old.[3] He later became the eastern district manager for North Carolina Theatres, Inc./Wilby-Kincey Theaters.[2] He spent a total of 55 years in cinema-related business[4] and served as a director of the N.C. Association of Theater Owners.[5]

In 1951 Enloe unsuccessfully sought a seat on the City Council of Raleigh, placing 10th in the primary election.[6] Two years later he was elected to the body.[7] In 1956 he was appointed to chair the "Let's Talk Sense Fund" to raise money for Adlai Stevenson II's presidential campaign.[8] He was elected Mayor of Raleigh the following year, succeeding Fred B. Wheeler on July 1, 1957.[9] That year he was also elected to the Executive Committee of the American Municipal Association, but he later left after choosing not to seek reelection.[10] He was reelected Mayor in 1961.[7] That spring the City Council resolved to ban ice cream trucks from operating on Raleigh's streets. Enloe supported the measure, citing increased road traffic and safety concerns for children. A United Press International report brought the event national attention, and Enloe received letters from across the country both praising and criticizing the council's action.[3] He was succeeded as Mayor by James W. Reid on July 1, 1963.[9] Enloe remained affiliated with North Carolina Theatres, Inc. during his tenure.[11] He also held the office of President of the North Carolina League of Municipalities, was a member of the Governor's School Study Commission, served as Secretary-Treasurer of the Mayors' Association of Wake County, was a member of the Executive Committee of the Governor's Highway Safety Conference,[7] and served as chairman of the Raleigh School Board.[12] In 1964 Enloe sought a seat in the North Carolina Senate for the 16th District.[13] He briefly served again as a Raleigh city councilman from 1971 until his death.[14]

Civil rights issues

In 1960 Enloe criticized black students who participated in the Greensboro sit-ins in protest of racial segregation, calling it "regrettable that some of our young Negro students would risk endangering [black and white] relations by seeking to change a long-standing custom in a manner that is all but destined to fail."[15] In March he appointed a 15-member biracial committee to negotiate an end to desegregation demonstrations.[16] The following month a white youth protesting segregated lunch counters in Raleigh was assaulted by a passerby. In response, Enloe convened an extraordinary session of the City Council to consider an ordinance that imposed restrictions on picketing, commenting that some demonstrators had been blocking the sidewalks in the downtown.[17] The biracial committee announced the integration of lunch counters in August, prompting the mayor to comment, "I appreciate the spirit of cooperation shown by all concerned and am proud of the acceptance shown by our citizens."[18]

-- Mayor William G. Enloe, May 9, 1963[19]

In the spring of 1963 the American South was subject to a wave of violence, demonstrations, and mass arrests spurred by racial tension. In early May, several Raleigh protests resulted in dozens of detentions.[19] Enloe, wanting to "avoid another Birmingham", appointed a biracial "Committee of One Hundred" to resolve the city's civil rights issues.[20] Among the targets of some anti-segregation demonstrators were cinemas owned by North Carolina Theatres, which were designed to accommodate Jim Crow-era segregation with separate seating arrangements. Enloe initially resisted the integration efforts.[21] A standoff between him and student protesters over the Ambassador Theater in Raleigh prompted Enloe to announce his intention to resign from office. He only withdrew his resignation after negotiations with black community leaders.[22] Eventually, in a meeting with United States Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, he agreed to begin desegregating the cinemas he managed, starting with those in Greensboro, then Winston-Salem, Charlotte, Durham, and finally Raleigh.[21] At the time he was considered moderate on the issue of race relations.[11]

Death

Enloe suffered a heart attack on November 2, 1972 while attending a North Carolina League of Municipalities convention in Greensboro. He died 20 days later at Rex Hospital in Raleigh.[2] He is buried next to his wife, Ruth Erskine Enloe, in Raleigh's Historic Oakwood Cemetery.[23] They had a son, William G. Enloe Jr., and a daughter, Ruth Enloe.[24]

Legacy

Enloe ... was considered during his time to be a progressive mayor with a businessman's point of view. His tenure was marked by the integration of Raleigh's schools in 1960 and sit-ins by black college students to protest racially segregated businesses.

— T. Keung Hui and Thomas Goldsmith, 2010[4]

In 1961, the Raleigh School Board voted to name a new school after Enloe. William G. Enloe High School opened the following year.[4] In 2010 the Wake County Public School Board voted to terminate a long-standing busing policy meant to increase schools' racial diversity. The decision generated criticism from the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and from historian Timothy Tyson, who emphasized that desegregation had been achieved with much difficulty in Raleigh and cited Enloe's statement on the participants in the Greensboro sit-ins as evidence. In response, members of the school board suggested that they would consider renaming Enloe High School after an African-American.[4] Several school students and alumni disapproved of the idea and created a Facebook group that opposed a name change, garnering the support of over 800 people. NAACP members stated that they were not seeking such an action, and NAACP leader William Barber II maintained that Tyson's remarks were only meant to contextualize the history of segregation in Wake County schools.[25]

Citations

- ↑ Enloe, William Gilmore (1942), Registration Card, Raleigh, North Carolina: National Archives and Records Administration

- 1 2 3 "W. G. Enloe dies: Veteran of 55 Years". Motion Picture Daily. Vol. 110 no. 78–102. New York: Quigley Publishing Company. 1972. p. 84. ISSN 0027-1594.

- 1 2 Sapir, Richard B. (May 25, 1961). "Ice Cream Truck Ban Praised And Panned". Tucson Daily Citizen. Raleigh, North Carolina: United Press International. p. 27.

- 1 2 3 4 Hui, T. Keung; Goldsmith, Thomas (June 23, 2010). "Enloe's name caught up in diversity debate". The News & Observer. Raleigh. Archived from the original on June 26, 2010. Retrieved May 18, 2018.

- ↑ "N.C. Moviehouse Owners Get Set To Fight DST". The Robesonian. Raleigh: Associated Press. January 25, 1967. p. 1.

- ↑ "Raleigh Election Brings Charges". Statesville Daily Record. Statesville, North Carolina: United Press International. May 2, 1951. p. 21.

- 1 2 3 "Meet Your Executive Committee". American Municipal Association Washington Newsletter. Chicago: American Municipal Association. OCLC 18830214.

- ↑ "Raleigh Man Heading Fund For Stevenson". Asheville Citizen-Times. Chicago. April 30, 1960. p. 3.

- 1 2 "History of Raleigh". City of Raleigh. February 16, 2018. Retrieved May 17, 2018.

- ↑ "Denver's Mayor Batterton Loses, Naftalin Wins in Minneapolis". American Municipal Association Washington Newsletter. Chicago: American Municipal Association. OCLC 18830214.

- 1 2 "Community Services". Wake County Public School System. Retrieved May 1, 2017.

- ↑ "Orange Crates In Valley Of Progress". The Danville Register. Danville, Virginia. June 27, 1962. p. 4.

- ↑ Shires, William A. (February 25, 1964). "Few 1963 Senators Will Return to Legislature". The High Point Enterprise. Raleigh. p. 5.

- ↑ Sharpe 2014, Appendix I : Raleigh City Council.

- ↑ Hunter-Gault 2012, p. 153.

- ↑ "26 Negroes Jailed; Sitdown Goes On". Arizona Republic. Phoenix, Arizona: Associated Press. March 5, 1960. p. 8.

- ↑ "Negro Students Meet To Discuss Strategy". The Courier-Journal. Louisville, Kentucky. April 16, 1960. p. 3.

- ↑ "Raleigh Integrates Counters". The High Point Enterprise. Raleigh, North Carolina: Associated Press. August 19, 1960. p. 6.

- 1 2 "Mayor Sounds Warning At Raleigh, N.C." Kingsport Times. Kingsport, Mississippi. May 10, 1963. p. 10.

- ↑ Grant 2009, p. 87.

- 1 2 Covington & Ellis 1999, p. 315.

- ↑ Suttell 2017, pp. 192–193.

- ↑ Historic Oakwood Cemetery (Raleigh, North Carolina), William Gilmore Enloe footstone, accessed May 14, 2017

- ↑ "In Memory of Ruth Enloe Hay". Brown-Wynne Funeral Home. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

- ↑ "Naming debate surrounds Raleigh high school". WRAL.com. Capitol Broadcasting Company, Inc. 29 June 2010. Retrieved May 18, 2018.

References

- Covington, Howard E.; Ellis, Marion A. (1999). Terry Sanford: Politics, Progress, and Outrageous Ambitions (illustrated ed.). Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press. ISBN 9780822323563.

- Hunter-Gault, Charlayne (2012). To the Mountaintop: My Journey Through the Civil Rights Movement (illustrated ed.). New York: Macmillan. ISBN 9781596436053.

- Grant, Gerald (2009). Hope and Despair in the American City. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674053922.

- Sharpe, John (2014). Growing Up With Raleigh: Smedes York Memoirs and Reflections of a Native Son, Conversations With John Sharpe. Raleigh, North Carolina: Lulu Press Inc. ISBN 9781483410760.

- Suttell, Brian William (2017). Campus to Counter: Civil Rights Activism in Raleigh and Durham, North Carolina, 1960–1963 (PDF) (PhD). University of North Carolina at Greensboro.