Ovis

- This article refers to the sheep genus. For the species commonly referred to as "sheep", see sheep (Ovis aries).

| Sheep | |

|---|---|

| |

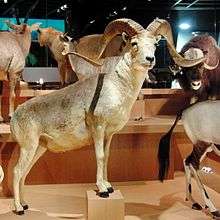

| Bighorn sheep | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Family: | Bovidae |

| Subfamily: | Caprinae |

| Genus: | Ovis Linnaeus, 1758 |

| Species | |

|

See text. | |

Ovis is a genus of mammals, part of the goat-antelope subfamily of the ruminant family Bovidae.[1] Its five or more highly sociable species are known as sheep. The domestic sheep is one member of the genus, and is thought to be descended from the wild mouflon of central and southwest Asia.

Terminology

Female sheep are called ewes, males are called rams (sometimes also called bucks or tups), and young sheep are called lambs. The adjective applying to sheep is ovine, and the collective term for sheep is flock or mob. The term herd is also occasionally used in this sense. Many specialist terms relating to domestic sheep are used.

Characteristics

Sheep are usually stockier than most other bovines, and their horns are usually divergent and curled into a spiral. Sheep have scent glands on their faces and feet. Communication through the scent glands is not well understood, but is thought to be important for sexual signaling. Males can smell females that are fertile and ready to mate, and rams mark their territories by rubbing scent on rocks. Like other ruminants, they have four-chambered stomachs, which play a vital role in digesting food; they eructate, and rechew the cud to increase digestion. Domestic sheep are used for their wool, milk, and meat (which is called mutton or lamb).

Species

Six species and numerous subspecies of sheep are currently recognized, although some subspecies have also been considered full species. These are the main ones:[1]

| Ovis ammon | Argali |

.jpg) | Ovis aries[2] | Domestic sheep |

| Ovis orientalis orientalis group | Mouflon |

| Ovis orientalis vignei group | Urial |

| Ovis canadensis | Bighorn sheep |

| Ovis dalli | Thinhorn sheep (a.k.a. Dall sheep) |

_by_Joseph_Smit.jpg) | Ovis nivicola | Snow sheep |

Behaviour

Wild sheep are mostly found in hilly or mountainous habitats. They are fairly small compared to other ungulates; in most species, adults weigh less than 100 kg (220 lb).[3] Their diets consist mainly of grasses, as well as other plants and lichens. Like other bovids, their digestive systems enable them to digest and live on low-quality, rough plant materials. Sheep conserve water well and can live in fairly dry environments. The bodies of wild sheep (and some domestic breeds) are covered by a coat of thick hair to protect them from cold. This coat contains long, stiff hairs, called kemps, over a short, woolly undercoat, which grows in autumn and is shed in spring.[4] This woolly undercoat has been developed in many domestic sheep breeds into a fleece of long wool, with selection against kemp hairs in these breeds. The fleece covers the body (in a few breeds also the face and legs) and is used for fibre.

Sheep are social animals and live in groups, called flocks. This helps them to avoid predators and stay warm in bad weather by huddling together. Flocks of sheep need to keep moving to find new grazing areas and more favourable weather as the seasons change. In each flock, a sheep, usually a mature ram, is followed by the others.[4]

In wild sheep, both rams and ewes have horns, while in domestic sheep (depending upon breed) horns may be present in both rams and ewes, in rams only, or in neither. Rams' horns may be very large – those of a mature bighorn ram can weigh 14 kg (31 lb) – as much as the bones of the rest of its body put together. Rams use their horns to fight with each other for dominance and the right to mate with females. In most cases, they do not injure each other because they hit each other head to head and their curved horns do not strike each other's bodies. They are also protected by having very thick skin and double-layered skulls.[5]

Wild sheep have very keen senses of sight and hearing. When detecting predators, wild sheep most often flee, usually uphill to higher ground. However, they can also fight back. The Dall sheep has been known to butt wolves off the face of cliffs.[5]

Overview of Mating System

The mating system of ovis is characterized by males competing for oestrus females.[6] Generally, males have a larger body masses than females; body mass in males is a factor involved in establishing dominance.[6] In ovis canadensis, beginning at six years of age males weigh 65% - 75% more than females.[6][7] This trend is also noticed in the other species of ovis. This genus is polygamous and characterized by males directly competing during the rut for access to females.[6][8] The purpose of male-male competition is to establish a dominance rank; higher ranked males achieve more successful matings.[6]

There are three common mechanisms used by males during the rut to gain access to the receptive females for copulation: tending, coursing, and blocking.[6] Tending occurs when a ram guards a ewe from other rams; this method appears to be cooperative and is typically performed only by high ranking males.[6] Coursing and blocking are methods used by lower ranked males.[6] Rams using coursing try to displace the tending ram, while in blocking rams use force to segregate ewes away from tending areas.[6]

Social rank in rams is established by male-male competition.[7] This competition can causes high energy expenditure and possible injuries in the combatants.[7] In the mating systems ovis, aggressive males establish themselves as dominant.[9] These males are typically 7 years of age or older.[9] In addition to aggression, high ranking males are also characterized by above average weight and gigantic horn size; these characteristics are linked with tending rams.[6] Rams that lack these large horns and increased weight instead use the technique of coursing.[6] With this technique, agility, endurance, and speed are critical for mating success.[6]

Females typically are separate from males outside the rut, however, during the rut females and males are found together.[8] Females that are oestrous isolate themselves from other ewes, and may be less mobile.[8] The rut is also linked with different ewe behaviour than during non-rutting periods.[8] These changes are characterized by decreased feeding, increased time observing their surroundings, and increased behaviour changes.[8] Ewes are also predicted to be slightly receptive to the displays of the rams.[8]

Sexual Selection

Social rank is highly linked with fitness in ovis, as a result traits that enhance the fitness of males are sexually selected for.[7] As horn size is critical to mating success in ovis species, it is a sexually selected trait.[6][10] Additionally, body size in rams is also a sexually selected trait.[7] When examining the underlying mechanisms of sexual selection in ovis, the following are present: male-male competition, indirect choice and female choice.[6][8][10][11][12] Additionally, sensory exploitation was investigated in this genus but lacked evidence to suggest that it plays a role in sexual selection.[13]

Male-male Competition

Male-male competition serves to establish dominance rank.[7] This competition arises from low ranking males having reduced mating success; it allows males to evaluate their opponents strength.[14] Unsuccessful individuals in social competition generally adapt a different method to acquire mates.[14] This is seen in ovis through the various different methods that males use to gain access to females during the rut.[6] The underlying mechanisms of male-male competition in this genus are: contests, weapons, and endurance rivalry.[12][15]

Contests

Contests are present in this genus and are common in the pre-rut period.[15] These contests are characterized by males fighting to establish a dominance rank; increased dominance rank leads to increased mating success in the rut.[7] During these contests, horn size, body size, age, and experience are critical to obtain dominance.[7] Typically, older rams rank higher as they have larger horns than the younger rams.[7] Additionally, older rams have greater experience in these contests which gives them a competitive advantage over the younger rams.[7]

Weapons

.jpg)

Weapons are structures used in antagonistic interactions.[12] In this genus, they are present in the form of horns and are involved in sexual selection; male horn type is related to reproductive success.[12] In males, two different types of horn types are present: full and reduced.[12] The rams that have full horns are more likely to have increased mating success on a yearly basis over rams with reduced horns.[12] This is due to increased horn size being associated with increased rank.[6]

Endurance Rivalry

Endurance rivalry is defined as having the capability to stay reproductively active for extended durations of time.[16] This is seen in ovis through the energy input required to grow the males horns and the male-male competition that establishes male ranking.[11][12] Testosterone levels in males are believed to improve the males' ability to compete by increasing their aggression levels.[11] Higher aggression in males has been linked with increased dominance.[9] Additionally, the ability of the males to engage in successful mating is related to horn size; bigger horned rams having greater reproductive success.[6] The energy investment required for males to grow horns and compete with other males is large.[8][10] As a result, rams with larger energy reserves establish dominance over other rams thus increasing their mating success.[6][10]

Indirect Mate Choice

Indirect mate choice includes: avoidance of the other sex, aggregation with individuals of the same sex also ready to mate, synchronization of mating susceptibility, advertisement of mating availability, and mating a designated areas.[17] This is seen in ovis with the ewes’ synchronization of mating susceptibility during the rut.[8] Female choice is also seen in this mating system.[8] Ewes choose to mate with males that use the tending technique.[6] This is likely due to tending rams offering oestrous females protection from the dangers associated with coursing and blocking.[8] Coursing and blocking may result in females being continually hassled leading to increased mortality due to rams potentially ramming into the ewes causing either physical harm or damage.[8]

See also

- Aries, the Ram (astrological sign)

- Barbary sheep (Ammotragus lervia), another type of goat antelope, not closely related to Ovis sheep

- Blue sheep or bharal (Pseodois), two species of goat antelopes, not closely related to Ovis

- List of sheep breeds

- Sheep husbandry

References

- 1 2 Grubb, P. (2005). "Order Artiodactyla". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 707–710. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ↑ ICZN (International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature) Opinion 2027

- ↑ Nowak, R. M. and J. L. Paradiso. 1983. Walker's Mammals of the World. Baltimore, Maryland: The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-2525-3

- 1 2 Clutton-Brock, J. 1999. A Natural History of Domesticated Mammals. Cambridge, UK : Cambridge University Press ISBN 0-521-63495-4

- 1 2 Voelker, W. 1986. The Natural History of Living Mammals. Medford, New Jersey: Plexus Publishing, Inc. ISBN 0-937548-08-1

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Coltman, D; Festa-Bianchet, M; Jorgenson, J; Strobeck, C (2002). "Age-Dependent Sexual Selection in Bighorn Rams". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 269 (1487): 165–172. doi:10.1098/rspb.2001.1851. PMC 1690873.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Pelletier, Fanie; Festa-Bianchet, Marco (2006). "Sexual Selection and Social Rank in Bighorn Rams". Animal Behaviour. 71 (3): 649–655. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2005.07.008.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Gonzalez, Georges; Bon, Richard; Estevez, Imna; Recarte, Jose (2001). "Behaviour of Ewes (Ovis Gmelini Musimon x Ovis Sp.) During the Rut". Rev. Ecol. 56: 221–230.

- 1 2 3 Réale, D; Martin, J; Coltman, D; Poissant, J; Festa-Bianchet, M (2009). "Male Personality, Life-history Strategies and Reproductive Success in a Promiscuous Mammal". Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 22 (8): 1599–1607. doi:10.111/j.1420-9101.2009.01781.x.

- 1 2 3 4 Loehr, J; Carey, J; Hoefs, M; Suhonen, J; Ylönen, H (2007). "Horn Growth Rate and Longevity: Implications for Natural and Artificial Selection in Thinhorn Sheep (Ovis dalli)". Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 20 (2): 818–828. doi:10.1111/j.1420-9101.2006.01272.x.

- 1 2 3 Pelletier, Fanie; Bauman, Joan; Festa-Bianchet, Marco (2003). "Fecal Testosterone in Bighorn Sheep (Ovis canadensis)". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 81 (10): 919–928. doi:10.1007/s00265-013-1516-7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Robinson, Matthew; Pilkington, Jill; Clutton-Brock, Tim; Pemberton, Josephine; Kruuk, Loeske (2006). "Live Fast, Die Young: Trade-Offs Between Fitness Components and Sexually Antagonistic Selection on Weaponry in Soay Sheep". Evolution. 60 (10): 2168–2181. doi:10.1554/06-128.1.

- ↑ Penn, Dustin (2002). "The Scent of Genetic Compatibility: Sexual Selection and the Major Histocompatibility Complex". Ethology. 950 (108): 929–950.

- 1 2 West-Eberhard, Mary Jane (1979). "Sexual Selection, Social Competition, and Evolution" (PDF). Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 123 (4): 222–234.

- 1 2 Martin, Alexandre; Presseault-Gauvin, Hélѐne; Festa-Bianchet, Marco; Pelletier, Fanie (2013). "Male Mating Competitiveness and Age-Dependent Relationship Between Testosterone and Social Rank in Bighorn Sheep". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 67 (6): 919–928. doi:10..1007/s00265-013-1516-7.

- ↑ Bercovitch, Fred (1997). "Reproductive Strategies in Rhesus Macaques". Primates. 38 (3): 247–263.

- ↑ Wiley, R; Poston, Joe (1996). "Indirect mate Choice, Competition for Mates, and Coevolution of the Sexes". International Journal of Organic Evolution. 50 (4): 1371–1381.

External links

- Miller, S. 1998. "Sheep and Goats". United States Department of Agriculture, Foreign Agricultural Service

- Oklahoma State University (OSU). 2003 Breeds of Livestock: Sheep Retrieved January 13, 2007

- Huffman, B. 2006. The Ultimate Ungulate Page Website Retrieved January 13, 2007