Northern giraffe

- See Giraffe for details of how this proposed taxonomy fits with the currently accepted taxonomy of giraffes.

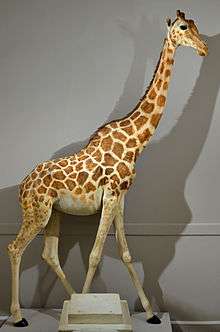

The northern giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis), also known as three-horned giraffe,[1] is a proposed species of giraffe native to North Africa.

In the current IUCN taxonomic scheme, there is only one species of giraffe with the name G. camelopardalis and nine subspecies.[2]

Once abundant throughout Africa since the 19th century, it ranged from Senegal, Mali and Nigeria from West Africa to up north in Egypt.[3] The West African giraffes once lived in Algeria and Morocco in ancient periods until their extinctions due to the Saharan dry climate.[4][5][3] It is isolated in South Sudan, Kenya, Chad and Niger.

All giraffes are considered Vulnerable to extinction by the IUCN.[2][6] In 2016, around 97,000 individuals from all subspecies were present in the wild.[6] There are currently 5,195 northern giraffes.

Taxonomy and evolution

| Internal systematics of giraffes (Fennessy et al. 2016)[7] | |||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

In the current IUCN taxonomic scheme there is only one species of giraffe with the name G. camelopardalis and nine subspecies.[6][8]

Subspecies

Three subspecies of northern giraffes are proposed.

| Subspecies | Description | Image |

|---|---|---|

| Nubian giraffe (G. c. camelopardalis)[9] | The nominate subspecies of the Northern giraffe, is found in eastern South Sudan and south-western Ethiopia.[10] It has sharply defined chestnut-coloured spots surrounded by mostly white lines, while undersides lack spotting. The median lump is particularly developed in the male.[11]:51 Around 2,150 are thought to remain in the wild, of which 1,500 are of the Rothschild ecotype.[7] It is one of the most common types of giraffe in captivity, although the original phenotype is rare- a group is kept at Al Ain Zoo in the United Arab Emirates.[12] In 2003, this group numbered 14.[13] | |

| Kordofan giraffe (G. c. antiquorum) | The Kordofan giraffe is a subspecies of the Northern giraffe (G. cameleopardis) and has a population of 2,000 in a distribution which includes southern Chad, the Central African Republic, northern Cameroon, and north-eastern DR Congo.[7] Populations in Cameroon were formerly included in G. c. peralta, but this was incorrect.[14] Compared to the Nubian giraffe, this subspecies has smaller and more irregular spotting patterns. Its spots may be found below the hocks and the insides of the legs. A median lump is present in males.[11]:51–52 Considerable confusion has existed over the status of this subspecies and G. c. peralta in zoos. In 2007, all alleged G. c. peralta in European zoos were shown to be, in fact, G. c. antiquorum.[14] With this correction, about 65 are kept in zoos.[15] The formerly recognised subspecies G. c. congoesis is now considered part of Kordofan subspecies. | _2.jpg) |

| Rothschild's giraffe ("G. c. rothschildi", after Walter Rothschild),[9] also known as Baringo giraffe or Ugandan giraffe | The Rothschild's giraffe is a former subspecies of the conglomerate Giraffa species, but it is now considered an ecotype of the Northern giraffe (Giraffa camleopardis). Its range includes parts of Uganda and Kenya.[2] Its presence in South Sudan and the Democratic Republic of Congo is uncertain.[16] This giraffe has large dark patches that usually have complete margins, but may also have sharp edges. The dark spots may also have paler radiating lines or streaks within them. Spotting does not often reach below the hocks and almost never to the hooves. This ecotype may also develop five "horns".[11]:53 Around 1500 are believed to remain in the wild,[7] and more than 450 are kept in zoos.[15] According to genetic analysis circa September 2016, it is conspecific with the Nubian giraffe (G. c. camelopardalis).[7] |  |

| The West African giraffe (G. c. peralta),[9] also known as Niger giraffe or Nigerian giraffe[17] | The West African giraffe is a subspecies of the Northern giraffe (G. cameleopardis) endemic to south-western Niger.[2] This animal has a lighter pelage than other subspecies,[18]:322 with red lobe-shaped blotches that reach below the hocks. The ossicones are more erect than in other subspecies and males have well-developed median lumps.[11]:52–53 It is the most endangered subspecies with fewer than 400 individuals remaining in the wild.[7] Giraffes in Cameroon were formerly believed to belong to this subspecies, but are actually G. c. antiquorum.[14] This error resulted in some confusion over its status in zoos, but in 2007, it was established that all "G. c. peralta" kept in European zoos actually are G. c. antiquorum.[14] |  |

Description

The giraffes have two horn-like protuberances known as ossicones on their foreheads. The northern giraffe's are longer and larger than that of the southern giraffes', though male northern giraffes have a third cylindrical ossicone in the center of the head just above the eyes which are from 3 to 5 inches long.[1]

Distribution and habitat

The Northern giraffes live in the savannahs, shrublands and woodlands. After local extinctions in various places, the Northern giraffes are the least numerous species and the most endangered. In East Africa, they are mostly found in Kenya and southwestern Ethiopia, though rarely in northeastern Democratic Republic of the Congo and South Sudan. There are about 2,000 in the Central African Republic, Chad and Cameroon of Central Africa. Once widespread in West Africa, a few hundreds of Northern giraffes are confined at the Dosso Reserve of Kouré, Niger. They are common in both in and outside of protected areas.[2]

The earliest ranges of the Northern giraffes were in Chad during the late Pliocene. were once abundant in North Africa. They lived in Algeria since early Pleistocene during the Quaternary period. They lived in Morocco until their extinction around the year AD 600, as the dry climate of the Sahara made conditions impossible for the giraffes.[4] They are also extinct in Libya and Egypt.[5]

References

- 1 2 Linnaeus, C. (1758). The Nubian or Three-horned giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis). Existing Forms of Giraffe (February 16, 1897): 14.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Muller, Z.; Bercovitch, F.; Brand, R.; Brown, D.; Brown, M.; Bolger, D.; Carter, K.; Deacon, F.; Doherty, J.B.; Fennessy, J.; Fennessy, S.; Hussein, A.A.; Lee, D.; Marais, A.; Strauss, M.; Tutchings, A. & Wube, T. (2016). "Giraffa camelopardalis". The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN. 2016: e.T9194A109326950. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T9194A51140239.en. Retrieved 23 December 2017.

- 1 2 Alexandre Hassanin, Anne Ropiquet, Anne-Laure Gourmand, Bertrand Chardonnet, Jacques Rigoulet : Mitochondrial DNA variability in Giraffa camelopardalis: consequences for taxonomy, phylogeography and conservation of giraffes in West and central Africa. C. R. Biologies 330 (2007) 265–274. online abstract

- 1 2 Anne Innis Dagg (23 January 2014). Giraffe: Biology, Behaviour and Conservation. Cambridge University Press. p. 5. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- 1 2 Fred Wendorf; Romuald Schild (11 November 2013). Holocene Settlement of the Egyptian Sahara: Volume 1: The Archaeology of Nabta Playa. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 622. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- 1 2 3 Muller, Z.; et al. (2016). "Giraffa camelopardalis (Giraffe)". www.iucnredlist.org. Retrieved 2017-05-02.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 http://www.cell.com/current-biology/abstract/S0960-9822(16)30787-4

- ↑ Bercovitch, Fred B.; Berry, Philip S. M.; Dagg, Anne; Deacon, Francois; Doherty, John B.; Lee, Derek E.; Mineur, Frédéric; Muller, Zoe; Ogden, Rob (2017-02-20). "How many species of giraffe are there?". Current Biology. 27 (4): R136–R137. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2016.12.039. ISSN 0960-9822. PMID 28222287.

- 1 2 3 Pellow, R. A. (2001). "Giraffe and Okapi". In MacDonald, D. The Encyclopedia of Mammals (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 520–27. ISBN 0-7607-1969-1.

- ↑ "Giraffe – The Facts: Current giraffe status?". Giraffe Conservation Foundation. Retrieved 21 December 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 Seymour, R. (2002) The taxonomic status of the giraffe, Giraffa camelopardalis (L. 1758), PH.D Thesis

- ↑ "Exhibits". Al Ain Zoo. 25 February 2003. Archived from the original on 2011-11-29. Retrieved 21 November 2011.

- ↑ "Nubian giraffe born in Al Ain zoo". UAE Interact. Archived from the original on 20 March 2012. Retrieved 21 December 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 Hassanin, A.; Ropiquet, A.; Gourmand, B.-L.; Chardonnet, B.; Rigoulet, J. (2007). "Mitochondrial DNA variability in Giraffa camelopardalis: consequences for taxonomy, phylogeography and conservation of giraffes in West and central Africa". Comptes Rendus Biologies. 330 (3): 173–83. doi:10.1016/j.crvi.2007.02.008. PMID 17434121.

- 1 2 "Giraffa". ISIS. 2010. Retrieved 4 November 2010.

- ↑ Fennessy, J. & Brenneman, R. (2010). "Giraffa camelopardalis ssp. rothschildi". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2012.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 2013-01-26.

- ↑ Fennessy, J.; Brown, D. (2008). "Giraffa camelopardalis ssp. peralta". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2012.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 2013-01-26.

- ↑ Kingdon, J. (1988). East African Mammals: An Atlas of Evolution in Africa, Volume 3, Part B: Large Mammals. University Of Chicago Press. pp. 313–37. ISBN 0-226-43722-1.