Who We Are and How We Got Here

Cover of 1st edition | |

| Author | David Reich |

|---|---|

| Subject | Human population genetics |

| Genre | Popular science |

| Publisher | Oxford University Press |

Publication date | 2018 |

Who We Are and How We Got Here is a 2018 book on the contribution of genome-wide ancient DNA research to human population genetics by the geneticist David Reich. He describes discoveries made by his group and others, based on analysis and comparison of ancient and modern DNA from human populations around the world. Central to these is the finding that almost all human populations are mixtures resulting from repeated population migrations and mixtures.

Scientists and critics have praised the book for the pioneering work that it describes. It has also been criticised for its dry style,[1] its political correctness,[1] and for skirting around entrenched attitudes of racism,[1] though other reviewers observe that nothing it says should give racists any comfort.[2]

Context

David Reich is a geneticist who has studied ancient human genomes, comparing their patterns of mutations to discover which populations migrated and mixed throughout prehistory.[3] He was mentored by the population geneticist Luca Cavalli-Sforza, who from 1960 pioneered the attempt to match the study of human prehistory by archaeology and linguistics, using the limited genetic data available at that time.[2]

Book

Publication

Who We Are and How We Got Here was published by Oxford University Press in 2018, ISBN 978-0-19-882125-0. It is credited to David Reich alone, but he explains in the Acknowledgements that the book grew from a detailed collaboration with his wife, Eugenie Reich.

The book is illustrated with monochrome maps, diagrams, and timelines. There are no photographs.

Summary

Since 2010, population geneticists have been able to sequence ancient human DNA, recovering complete genomes,[2] in contrast to earlier approaches which relied on the far more abundant (and hence more easily recovered) mitochondrial DNA, which is present in many copies in each cell, and transmitted only via the maternal line. That early work gave the "exciting" result that all modern humans are related to "Mitochondrial Eve", a woman who lived in Africa only about 160,000 years ago.[4][5]

The whole genome recovery technique, using the especially hard bone from the inner ear of ancient skeletons -- along with the genomes of modern people from different parts of the world, including especially some isolated populations -- has made it possible to reconstruct prehistoric migrations and mixing of populations in the past 5,000 years, and to make reliable inferences about mixtures from much further back in time.[2] The new knowledge from genomics has overthrown many old assumptions about human origins.[2]

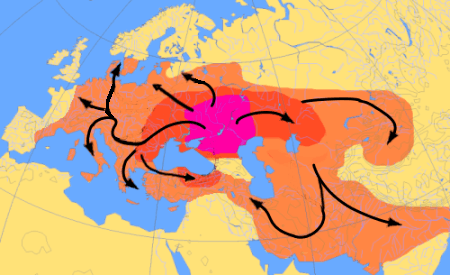

Much of the work has focussed on Western Eurasia, where in 1786 Sir William Jones discovered that Sanskrit and ancient Greek were related languages. Linguists came to recognise the Indo-European family of languages, spanning Germanic, Celtic, Italic, Iranian and northern Indian languages, but without explaining how these came to be. Reich showed that modern populations in Europe and north India derive from mixing of native populations with Yamnaya people from the steppes north of the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea some 5,000 years ago, in separate migrations to the west and the east.[2][6] Corded ware culture described by archaeology corresponds to a stage in the westward migration.[2]

Similar migrations and population mixtures characterise human prehistory on all continents.[2] Reich shows that people in Japan and Korea share some 80% of their DNA, implying migration; Polynesians migrated relatively recently, in just the past few thousand years, from the region of Taiwan. The evidence can upset long-held beliefs: Native American skeletons from 10,000 years ago do not appear to be related to the tribes living in those regions today who have been asking for the ancient bones to be returned to them for burial.[4]

The Neanderthals are extinct, but part of their genome survives: All present-day non-Africans have at least 2% of Neanderthal ancestry. Reich explains that somewhere between 100,000 and 50,000 years ago, modern humans mated with Neanderthals, and their descendants carried those genes all over the world. An ancient skeleton from Romania had up to 9% Neanderthal DNA, so natural selection has been removing Neanderthal genes since those matings.[4]

Reception

Favourable

Jared Diamond, in the New York Times, notes that geneticists can now go far beyond studying the personal ancestries of participants in National Geographic's Genographic Project, which looked at small sections of their parents' DNA, namely their mother's mitochondrial DNA and their father's Y chromosome. By looking at DNA from ancient bones, Reich can recover whole genomes. Diamond warns readers not to expect an oversimplified story:[4]

Population genetics is a complicated, fast-moving field with many uncertainties of interpretation. To tell that story to the broad public, and not just to scientists reading specialty journals, is a big challenge. Reich explains these complications as well as any geneticist could; others rarely even try.[4]

Peter Forbes, in The Guardian, calls the book "thrilling in its clarity and its scope."[2] In Forbes's view, Reich handles racist abuses of human origin stories, such as Nazi ideology, "commendably". Forbes writes that Reich explains how ancient DNA teaches a single general lesson, that the human population of any particular place has repeatedly changed since the last ice age; any supposed "mystical, longstanding" link between some people and a place, based on some kind of racial purity, is in Reich's words "flying in the face of hard science".[2]

Clive Cookson, in the Financial Times, writes that one of the first and most surprising impacts of genomics is in human prehistory, and Reich is the first leading practitioner to write a popular book about this. Cookson calls the book[7]

a marvellous synthesis of the field: the technology for purifying and decoding DNA from old bones; what the findings tell us about the origins and movements of people on every inhabited continent; and the ethical and political implications of the research.[7]

Cookson notes that Reich dismisses worries that DNA evidence of differences between populations is "racism in genetic clothing",[7] and that on the contrary, the "unsuspected degree of mixing"[7] in every part of human history makes old ideas of racial purity "absurd".[7]

The archaeologist and geneticist Turi King, in Nature, writes that Reich's laboratory "has developed some of the most sophisticated statistical and bioinformatics techniques available. Using computers, they painstakingly reconstruct genomic information from fragments of DNA from ancient individuals. They then drill down in search of a new understanding of human history." King notes that Reich's group helped to show that "Neanderthals interbred with the ancestors of all modern humans descended from Europeans, Asians and other non-Africans." Their work is showing the "tremendous degree to which populations globally are blended, repeatedly, over generations." King notes, too, that Reich reflects on the dangers of misinterpretation by racists, who "pick and choose results", or others who opt to "sweep [genetic] differences under the carpet". But, King argues, echoing Reich, we do need "a non-loaded way to talk about genetic diversity and similarities in populations", and Reich has begun to do that.[8]

The economist Tyler Cowen calls the book "truly excellent, readable and informative". Cowen insists it is "a science book, not a 'race book'", stating that although it has engendered "some public controversy", he is confident that no attentive reader could feel "affirmed in racist beliefs".[9]

The educator Darcy Moore of the University of Wollongong calls the book "highly recommended" but finds some of Reich's conclusions "puzzling and in need of much more research and explanation." A case in point is Reich's statement that the population of Britain was 90% replaced by the incoming Indo-Europeans at the start of the Beaker period. Moore comments that he and the archaeologist Barry Cunliffe (who along with the archaeologist Colin Renfrew praises the book on its back cover) agreed in an email discussion that such a radical change was difficult to understand.[10]

Unfavourable

An open letter "by a group of 67 scientists and researchers" including anthropologists, sociologists, historians, and others takes Reich to task for his book, under the heading "How Not To Talk About Race And Genetics".[11] The group welcomes Reich's challenge to the "misrepresentations about race and genetics"[11] made by the science writer Nicholas Wade and the molecular biologist James Watson, but warns that his skill with genomics "should not be confused with a mastery of the cultural, political, and biological meanings of human groups."[11] The group argues that Reich's understanding of "race" [their quotation marks] "is seriously flawed",[11] and that "biological traits" like sickle cell anaemia have "nothing to do with"[11] race, but are simply found in parts of the world, in this case where malaria is common. The same goes, the group argues, for other distinctions that Reich makes in the book.[11]

Maria C. Avila Arcos reviews the book in Science magazine, arguing that "troubling traces of biocolonialism undermine an otherwise eloquent synthesis of ancient genome research."[12] She calls Reich's account graceful, combining his personal opinions with "hard science"[12] (Reich's phrase). She accepts that the book is "scientifically solid and comprehensive",[12] but argues that it "raises some concerns",[12] since in her view Reich overlooks the conflict of interest between the needs of researchers to gather ancient human DNA specimens and the rights of the often marginalised populations that descend from those ancestors.[12]

The writer John Derbyshire notes that there has been a public debate about the book because it touches on the issue of race. He agrees that Reich's work is "of the highest degree of difficulty and deep intellectual complexity. If you get nothing else from Prof. Reich's book, you will come away in awe at the diligence and ingenuity he and his colleagues have brought to their research."[1] He also found some of Reich's discoveries, like the extraordinary genetic isolation of India's caste system, "Amazing and fascinating".[1] In Derbyshire's view, while the public can hardly judge the value of Reich's work, they can certainly pass judgement on how well the book is written, how difficult it is to read, "and whether, when the author steps outside his specialist sphere, he says sensible things about other subjects."[1] On this side of things, Derbyshire believes three things are wrong with the book. First, he finds the style[1]

"...dry and lifeless. There is very little of what makes reading pleasurable: colorful metaphors, amusing asides, rhetorical acrobatics, sly allusions, interesting historical or biographical titbits, snippets of verse. I'm certainly willing to believe that Prof. Reich is a very good scientist. He's just not a very good writer."[1]

This opinion is confirmed by the generally positive review for National Review Online, previewed on Gene Expression, by Razib Khan. He states that the book "is not rich with the same stylistic flourish and engagement as one might find in a popularization by Steven Pinker or Richard Dawkins."[13]

Second, Derbyshire finds the science "not well explained",[1] leading him to re-read some passages to work out what Reich had meant. Thirdly, Derbyshire finds the last part of the book, where Reich discusses the impact genomics may have on social inequality, race, identity, and archaeology, a lamentable attempt "to twist a dull but informative book into ideological orthodoxy."[1] On the "mixture" of different populations, Derbyshire notes Reich's enthusiasm for the oft-repeated word, quoting what he says in Chapter 4: "Mixture is fundamental to who we are, and we need to embrace it, not deny that it occurred."[1] But how, Derbyshire asks, did this mixing actually occur? It is, he writes, "rather awkward". He points out, among Reich's own examples, that Bantu men overwhelmingly mixed with pygmy women; that in the isolated Antioquia region of Colombia, 94% of the men's Y chromosomes are European, but 90% of the female ancestors' mitochondrial DNA is native American; that in India, too, the incoming population contributed male DNA, the native population female. He concludes that: [1]

It is plain from the evidence, amply presented in this book, that many—perhaps most—of the 'mixture' events Prof. Reich urges us to 'embrace' in fact involved one group of human males killing off another group's males and mating with their females.[1]

Derbyshire is unsure whether the combination of Reich's directness and his "PC pablum" on "race realism" is due to the need to maintain funding from his sponsors, or a genuine mental struggle between reality and ideology.[1]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Derbyshire, John (19 April 2018). "John Derbyshire: Ideology Beats Reality In Reich's Who We Are and Who We Got Here". Retrieved 7 May 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Forbes, Peter (29 March 2018). "Who We Are and How We Got Here by David Reich review – new findings from ancient DNA". The Guardian. Retrieved 6 May 2018.

- ↑ Callaway, Ewen (17 December 2015). "365 days: Nature's 10 | DAVID REICH: Genome archaeologist". Nature Magazine. Retrieved 6 May 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Diamond, Jared (20 April 2018). "A Brand-New Version of Our Origin Story | 'WHO WE ARE AND HOW WE GOT HERE' Ancient DNA and the New Science of the Human Past By David Reich". The New York Times.

- ↑ Reich 2018, pp. 4–5.

- ↑ Haak, Wolfgang; Lazaridis, Iosif; Patterson, Nick; et al. (2015-03-02). "Massive migration from the steppe was a source for Indo-European languages in Europe". Nature. 522 (7555): 207–211. doi:10.1038/nature14317. PMC 5048219.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Cookson, Clive (23 March 2018). "Who We Are and How We Got Here by David Reich — out of Africa and back again? | How ancient DNA is showing early human migrations to be more complex than once thought". Financial Times.

- ↑ King, Turi (13 March 2018). "Sex, power and ancient DNA | Turi King hails David Reich's thrilling account of mapping humans through time and place" (PDF). Nature. 555: 307–308. doi:10.1038/d41586-018-02964-5.

- ↑ Cowen, Tyler. "*Who We Are and How We Got Here*, by David Reich". Retrieved 7 May 2018.

- ↑ Moore, Darcy (27 April 2018). "Who We Are and How We Got Here by David Reich #review". Retrieved 7 May 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Kahn, Jonathan, and 66 other signatories. "Opinion | How Not To Talk About Race And Genetics". BuzzFeed News. Retrieved 5 May 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Avila Arcos, Maria C. (17 April 2018). "Troubling traces of biocolonialism undermine an otherwise eloquent synthesis of ancient genome research". Science. Retrieved 5 May 2018.

- ↑ Khan, Razib (18 March 2018). "A preview review of Who We Are and How We Got Here: Ancient DNA and the New Science of the Human Past". Gene Expression. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

Sources

- Reich, David (2018). Who We Are and How We Got Here. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-882125-0.