Veblen good

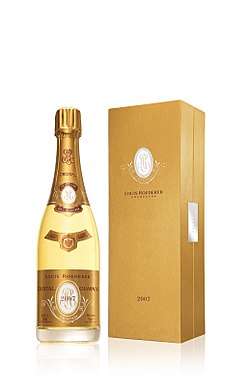

Veblen goods are types of luxury goods for which the quantity demanded increases as the price increases, an apparent contradiction of the law of demand, resulting in an upward-sloping demand curve. For example, in the 1990s when "fashion" jeans became popular, one retailer found that he could sell more when he raised the price. Some wines, jewelry, fashion-designer handbags, and luxury cars are in demand because of, rather than in spite of, the high prices asked for them. This makes them desirable as status symbols in the practices of conspicuous consumption and conspicuous leisure. A product may be a Veblen good because it is a positional good, something few others can own.

Veblen goods are named after American economist Thorstein Veblen, who first identified conspicuous consumption as a mode of status-seeking in The Theory of the Leisure Class (1899).[1] A corollary of the Veblen effect is that lowering the price decreases the demand.[2]

Related concepts

The Veblen effect is one of a family of theoretically possible anomalies in the general law of demand in microeconomics. Other related effects include:

- The snob effect: expressed preference for goods because they are different from those commonly preferred; in other words, for consumers who want to use exclusive products, price is quality.[3]

- The common law of business balance: low price of a good indicates that the producer may have compromised quality, that is, "you get what you pay for".

- The hot-hand fallacy: stock buyers have fallen prey to the fallacy that previous price increases suggest future price increases.[4] Other rationales for buying a high-priced stock are that previous buyers who bid up the price are proof of the issue's quality, or conversely, that an issue's low price may be evidence of viability problems.

Sometimes, the value of a good increases as the number of buyers or users increases. This is called the bandwagon effect when it depends on the psychology of buying a product because it seems popular; or the network effect, when a large number of buyers or users itself increases the value of a good. For example, as the number of people with telephones or Facebook increased, the value of having a telephone or being on Facebook increased, since the user could reach more people. However, neither of these effects suggests that, at a given level of saturation, raising the price would boost demand.

Some of these effects are discussed in a classic article by Leibenstein (1950).[5] Counter-examples have been called the counter-Veblen effect.[6]

The effect on demand depends on the range of other goods available, their prices, and whether they serve as substitutes for the goods in question. The effects are anomalies within demand theory, because the theory normally assumes that preferences are independent of price or the number of units being sold. They are therefore collectively referred to as interaction effects.

The interaction effects are a different kind of anomaly from that posed by Giffen goods. The Giffen goods theory is one for which observed demand rises as price rises, but the effect arises without any interaction between price and preference—it results from the interplay of the income effect and the substitution effect of a change in price.

Studies have examined cases of goods which show interaction effects,[7][8] and in which people seem to receive more pleasure from more expensive goods.[9]

See also

References

- ↑ Veblen, T. B. (1899). The Theory of the Leisure Class. An Economic Study of Institutions. London: Macmillan Publishers.

- ↑ John C. Wood (1993). Thorstein Veblen: Critical Assessments. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-07487-2.

- ↑ Galatin, M.; Leiter, Robert D. (1981). Economics of Information. Boston: Martinus Nijhoff. pp. 25–29. ISBN 0-89838-067-7.

- ↑ Johnson, Joseph; Tellis, G.J.; Macinnis, D.J. (2005). "Losers, Winners, and Biased Trades". Journal of Consumer Research. 2 (32): 324–329. doi:10.1086/432241.

- ↑ Leibenstein, H. (1950). "Bandwagon, Snob, and Veblen Effects in the Theory of Consumers' Demand". Quarterly Journal of Economics. 64 (2): 183–207. doi:10.2307/1882692.

- ↑ Lea, S. E. G.; Tarpy, R. M.; Webley, P. (1987). The individual in the economy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-26872-9.

- ↑ Chao, A.; Schor, J. B. (1998). "Empirical tests of status consumption: Evidence from women's cosmetics". Journal of Economic Psychology. 19 (1): 107–131. doi:10.1016/S0167-4870(97)00038-X.

- ↑ McAdams, Richard H. (1992). "Relative Preferences". Yale Law Journal. 102 (1): 1–104. JSTOR 796772.

- ↑ "Price tag can change the way people experience wine, study shows". news-service.stanford.edu.