Vardar Macedonia

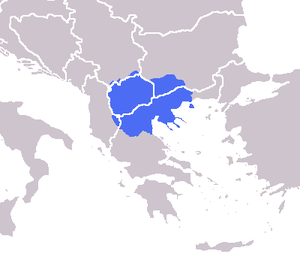

Vardar Macedonia (Macedonian and Serbian: Вардарска Македонија, Vardarska Makedonija) was the name given to the territory of Kingdom of Serbia and Kingdom of Yugoslavia roughly corresponding to today's Republic of Macedonia. It covers the northwestern part of geographical Macedonia, whose modern borders came to be defined by the mid 19th century.

Geography

It usually refers to the part of the region of Macedonia attributed to the Kingdom of Serbia by the Treaty of Bucharest (1913). The territory is named after the Vardar, the major river in the area. Officially, the area (including parts of today Kosovo and Eastern Serbia) was called Southern Serbia (Serbian: Jужна Србија, Južna Srbija),[1][2][3] later Vardar Banovina, because the very name Macedonia was prohibited in Serbia, later the Kingdom of Yugoslavia.[4][5] After World War I, the present-day Strumica and Novo Selo municipalities were broken away from Bulgaria and ceded to Yugoslavia. After WWII most of the area became part of SFR Yugoslavia as SR Macedonia. After the breakup of Yugoslavia, besides the Republic of Macedonia, the region encompasses also Trgovište and Preševo municipalities in Serbia,[6] as well the Elez Han municipality in Kosovo.[7] Sometimes in the region are included the areas of Golo Brdo and Mala Prespa in Albania.

History

Background

Yugoslavia

Republic of Macedonia

See also

References

- ↑ Victor Roudometof, Collective Memory, National Identity, and Ethnic Conflict: Greece, Bulgaria, and the Macedonian Question, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2002, ISBN 0275976483, p. 102.

- ↑ Constantine Panos Danopoulos, Dhirendra K. Vajpeyi, Amir Bar-Or, Civil-military Relations, Nation Building, and National Identity: Comparative Perspectives, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2004, ISBN 0275979237, p. 218.

- ↑ Roland Robertson, Victor Roudometof, Nationalism, Globalization, and Orthodoxy: The Social Origins of Ethnic Conflict in the Balkans, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2001, ISBN 0313319499, p. 188.

- ↑ Donald Bloxham, The Final Solution: A Genocide, OUP Oxford, 2009, ISBN 0199550336, p. 65.

- ↑ Chris Kostov, Contested Ethnic Identity: The Case of Macedonian Immigrants in Toronto, Peter Lang, 2010, ISBN 3034301960, p. 76.

- ↑ Петър Христов Петров, Македония: история и политическа съдба, том 3, Изд-во "Знание" ООД, 1998, стр. 109.

- ↑ Стефан Карастоянов, Косово: геополитически анализ, Университетско издателство "Св. Климент Охридски", 2007, ISBN 9540725410, стр. 41.

Further reading

- Danforth, L.M. (1997). The Macedonian Conflict: Ethnic Nationalism in a Transnational World. Princeton University Press. p. 44. ISBN 0-691-04356-6

- Alice Ackermann (1999). Making Peace Prevail: Preventing Violent Conflict in Macedonia. Syracuse University Press. pp. 55–. ISBN 978-0-8156-0602-4.

- Ilká Thiessen (2007). Waiting for Macedonia: Identity in a Changing World. University of Toronto Press. pp. 29–. ISBN 978-1-55111-719-5.

- Hugh Poulton (2000). Who are the Macedonians?. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. pp. 2–. ISBN 978-1-85065-534-3.

- Stefan Troebst (January 2007). Das makedonische Jahrhundert: von den Anfängen der nationalrevolutionären Bewegung zum Abkommen von Ohrid 1893-2001 ; ausgewählte Aufsätze. Oldenbourg. pp. 344–. ISBN 978-3-486-58050-1.

- Dimitar Bechev (13 April 2009). Historical Dictionary of the Republic of Macedonia. Scarecrow Press. pp. 232–. ISBN 978-0-8108-6295-1.