Vale Royal Abbey

| Monastery information | |

|---|---|

| Full name | The Abbey Church of St Mary the Virgin, St Nicholas, and St Nicasus, Vale Royal |

| Other names | Vale Royal Abbey |

| Order | Cistercian |

| Established | 1270/1277 |

| Disestablished | 1538 |

| Mother house | Dore Abbey |

| Dedicated to | Virgin Mary, St Nicholas, St Nicasus |

| Diocese | Diocese of Lichfield |

| Controlled churches | Frodsham, Weaverham, Ashbourne, Castleton, St Padarn's Church, Llanbadarn Fawr |

| People | |

| Founder(s) | Edward I |

| Important associated figures | Edward I, Thomas Holcroft |

| Site | |

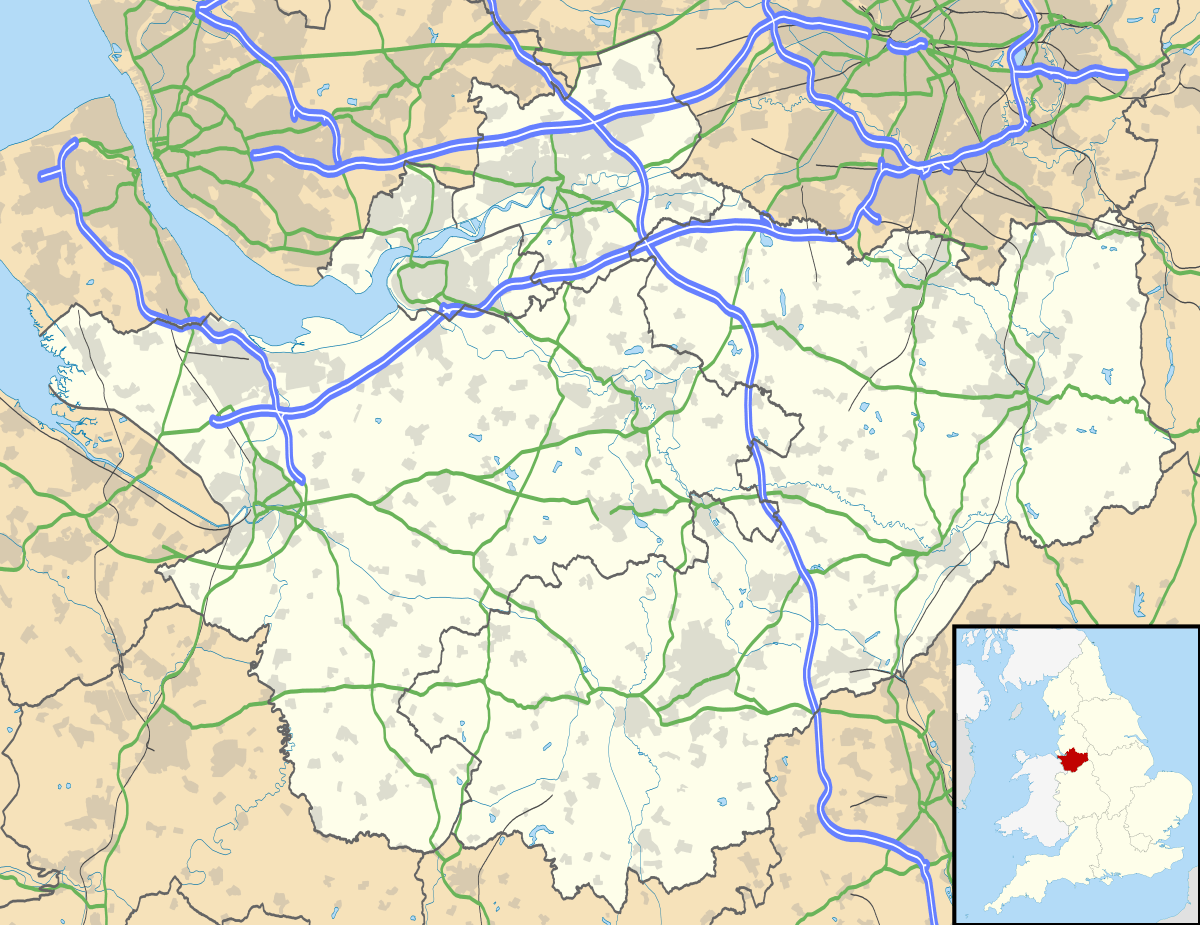

| Location | Whitegate, Cheshire, United Kingdom |

| Visible remains | Foundations of the church, surviving rooms within later house, earthworks. Gate chapel survives as parish church |

| Public access | No, the abbey is now a private golf club |

Vale Royal abbey is a medieval abbey, and later a country house, located in Whitegate, between Northwich and Winsford in Cheshire, England.

The abbey was founded in 1270 by Edward I for monks of the austere Cistercian order. The king intended the abbey to be on the grandest scale. However, financial difficulties meant that these ambitions could not be fulfilled and the final building was considerably smaller than planned. The project ran into problems in other ways. The abbey was frequently grossly mismanaged, relations with the local population were so poor as to regularly cause outbreaks of large-scale violence on a number of occasions and internal discipline was frequently bad.

Vale Royal was closed in 1538 by Henry VIII as part of the Dissolution of the Monasteries. Much of the abbey, including the church, was demolished but some of the cloister buildings were incorporated into a mansion by Thomas Holcroft, an important government official, during the 1540s. Over subsequent centuries this house was considerably altered and extended by successive generations. The building remains habitable and contains surviving rooms from the medieval abbey, including the refectory and kitchen. The foundations of the church and cloister have been excavated. It is a scheduled ancient monument,[1][2] and recorded in the National Heritage List for England as a designated Grade II* listed building.[3]

Foundation

The abbey now known as Vale Royal was founded by Prince Edward, the future Edward I, before his accession to the throne. In 1263 the prince was undertaking a sea voyage from France when his ship was caught in a terrible storm. He then made a vow that if he came safe to land he would found an abbey of unprecedented size and grandeur as a thanksgiving to God for saving him. Political problems and civil war meant that the vow could not be fulfilled immediately, but by 1266 negotiations were in hand for the establishment of a monastery of Cistercian monks in the secluded location of Darnhall in Cheshire.[4] In August 1270, Edward granted a charter to his new abbey along with an endowment of lands and churches.[5]

As so often in the history of the abbey things did not go smoothly; preparing the site took considerable time and the first monks, led by Abbot John Chaumpeneys,[4] did not arrive at Darnhall from Dore abbey until 1274.[5] The foundation of the new abbey provoked anger, resentment and strong resistance from the people of the area as its existence and the grants of land required, locals claimed, impinged on villagers' customary liberties.[6] The abbey was, for example, granted the forestry rights and free warren of Darnhall.[4]

The Darnhall site itself was, however, soon found to be unsuitable for the huge buildings planned.[4][5][note 1] It may be that it had only ever been intended as a temporary site.[7] In 1276 Edward, by now King agreed to move the abbey to a better site and a location was chosen in nearby Over on the edge of the Forest of Mondrem. With its foundation, the new ecclesiastical site was named Vale Royal. On 13 August 1277 the King and Queen Eleanor, their son Alphonso[note 2] and numerous great nobles[note 3] arrived at Over to lay the foundation stones of the new abbey.[4] Following this, Chaumpeneys performed a celebratory Mass.[9] In 1281 the monks moved from Darnhall to temporary accommodation on the Vale Royal site while the abbey started to rise around them—what was intended to be the biggest and grandest Cistercian church in Christian Europe.[10]

The precise siting of the new institution, and its boundaries, in a modern landscape is hard to assess. Broadly, it was within the monks' new manor of Conersley, on parcels of land that were renamed Vale Royal to indicate the abbey's status as occupier. The southern point was probably around Petty Pool, past Earnslow, to the Weaver (where the abbey's fishponds were), then following the river as far as Bradford Mill: an area of approximately 400 acres (160 ha).[7]

Estates and finances

The village of Over was the natural centre of the abbey's estates, and was now, like the surrounding villages, under the Abbot's feudal lordship.[11] The abbey's original endowment at Darnhall included not only the site of the establishment in Delamere Forest, but also the manors of Darnhall Langwith in the East Riding of Yorkshire, and the advowsons of Frodsham, Weaverham, and Ashbourne and Castleton.[4] These included Conewardsly (granted in 1276), followed in 1280 by Wirral lands (some distance away notwithstanding), and in 1285 they received various manors belonging to members of the local gentry, including those of Hugh de Merton around Over, as well as Bradford and Guilden Sutton.[11]

The abbey possessed a glass making forge, which was a useful source of income.[7] However, wool exports were the abbey's main source of income. In 1283, Abbot Chaumpeneys acknowledged receipt of 53s 6d 8p as an advance on the abbey's eventual delivery of twelve sacks of collecta. These transactions were paid for before the merchant sold on on the proviso that it was put to the "common profit of his house."[12] In all, by the mid-1330s, Abbot Peter calculated that the abbey's income was £248 17s, of which £60 was consumed by hospitality;[note 4] this compared to £16 in wages for the abbey's servant staff, £21 in expenses for the abbot, £30 for defensive measures, and £50 in "gifts, damages and contributions."[11] The remainder—insufficiently, said Abbot Pete in 1336—went on the everyday needs of the monks.[11] And by 1342, under the abbacy of Robert de Cheyneston, the abbey was £20 in debt, and a fire had burnt down the abbey's monastic granges at Bradford and Hefferston. This meant not only that they lost all the corn that was being stored in them when it happened, but also had to go and purchase more corn to live on until the next harvest.[15] He complained that he required £100 to repair the granges and their weirs, as well as parts of the church roof and the abbey building itself.[11]

Vale Royal's finances seem to have improved by the 15th century. Two taxes assessed the abbey at respectively £346 0s. 4d and, twenty-six years later, at £540 6s 2d. Not only were incomes up, but costs were down: of the first, only about £92 was ever spent, and of the latter only slightly over £21. The abbey was also wealthy in goods and possessions and oxen; however, it also had far fewer monks then historically intended: The Abbot of Dore, visiting Vale Royal in 1509, found only fifteen resident out of a supposed complement of thirty.[10]

Construction

King Edward had vast ambitions for Vale Royal. It was intended to be an abbey of the first importance, to surpass all the other houses of its order in Britain in scale and beauty and provide a fitting symbol of the wealth and power of the English monarchy and Edward's piety and personal greatness.[5] The plans for the buildings reflected this. Royal masons under the leadership of Walter of Hereford,[5] one of the foremost architects of his day, started work on a huge and elaborate high gothic church the size of a cathedral. It was to be 116m long and cruciform in shape with a central tower.[16] The east end was semi-circular with a chevet of 13 radiating chapels, some square, some polygonal; each of the transepts also had a row of three chapels on its eastern side.[16] South of the church stood a cloister, 42m square, surrounded by the domestic buildings of the house, which were to be of a scale and grandeur to match the church.[16]

At first matters went well. The king greatly expanded the initial endowment and made large donations of cash and materials. for the work.[4] Initially providing 1,000 marks in cash for the project, the King also provided the monks with revenues from his earldom of Chester. Furthermore, the Justice of Chester had been instructed to release the same amount annually in 1281.[7] Two years later, sufficient progress had been made to allow the new church to be consecrated, and this was done by the Bishop of Durham, Anthony Bek. The King attended the service with his court.[7]

Soon, however, things began to go seriously wrong. As the 1280s progressed the royal finances first got into arrears and eventually dried up completely. King Edward needed money to pay for his numerous wars and workmen to build the great castles such as Harlech he put up to cement his conquest of Wales. He took not only the money that had been set aside for Vale Royal but also conscripted the masons and other labourers to build his Welsh fortifications.[17] With unfortunate timing, this was around the time that building work began on the monks' own cloister, which were to possess marble columns shipped from the south of England.[10]

Then, in 1290 he announced that he was no longer interested in the abbey: "The King has ceased to concern himself with the works of that church and henceforth will have nothing more to do with them." Once-large royal grants became meagre.[18] The monks were left struggling to pay to complete the vast project and provide the running costs of it all by themselves, a task that would prove beyond their means. Despite possessing a substantial income, the abbey incurred huge debts to other church institutions, royal officials, the building contractors and even to the merchants of Lucca.[4][note 5] It is even possible that funds were being misappropriated.[10] Work stopped for at least a decade after 1290 and was resumed only on a much-reduced scale thereafter.[4]

Nevertheless, by the 1330s the monks had managed to complete the east end of the church (the rest remained a shell) and sufficient of the cloister buildings to make the place habitable, though far from complete.[16]

In 1353 there was cause for renewed hope. Edward the Black Prince took an interest in completing the abbey and donated substantial funds to the job.[4][16] This amounted to 500 marks in cash immediately, and the same amount was to be paid five years later,[11] when the prince personally visited Vale Royal.[4] Also to this end, in 1359, Prince Edward granted Vale Royal the advowson and church of Llanbadarn Fawr, Ceredigion to supply further financing for the building works.[10][note 6] These works were expected to take six years.[10]

Work began on completing the shell of the nave and making the east end even grander. It was based somewhat on the design ("then novel in England") of Toledo Cathedral.[10] However, the following year, in October 1359, during a massive storm, much of the nave (including the new lead roof put in place by the previous abbot) was blown down and destroyed, the arcades of the unfinished nave crashing down in ruins.[20] The destruction was comprehensive, ranging "from the wall at the west end to the bell-tower before the gates of the choir," whilst the timber scaffolding collapsed "'like trees uprooted by the wind."[21]

Repairs slowly took place over the next thirteen years, and Abbot Thomas may have been responsible for the "unique chevet of seven radiating chapels" that were installed.[22] Work was still taking place in 1368 when the Prince of Wales recommissioned the masons.[10] However, the overall stature of the remodelled church was to be smaller than before,[22] with the nave reduced both in height and width.[10] This was the result of an agreement—under the patronage of Richard II—to finish the abbey on a much-reduced scale from what was originally planned.[23]

Repairs and building work continued sporadically into the 15th century, with, for instance, a new aisle being installed in the middle of the church in 1422.[22]

Relations with the tenantry

As well as the burden of trying to finish the abbey buildings, Vale Royal faced many other serious problems. From the beginning the monks' relationship with their tenants and neighbours was usually poor and sometimes abysmal.[6][25][note 7] The initial foundation was resented by the people of Darnhall and Over who found themselves under the lordship of the abbey; this made the previously free tenants villeins,[note 8] and in 1275, only a year after the abbey's foundation, tenants of Darnhall attempted to withdraw from paying the abbot customs and services, and continued to feud with various abbots of Vale Royal of the matter with increasing vigour for the next fifty years.[25] The original cause of the dispute was probably over forestry rights. The new abbey was wholly within the boundaries of the forest of Mondrem, which until it was granted to the new house, was mostly common land. But keeping it thus would have effectively prevented the monks from utilising its value, so the abbey was granted immunity from the foresting laws—in which, it is almost certain, the abbey regularly over-reached itself.[10][note 9]

Abbots were not just abbots; they were also feudal lords, and as such should not be assumed to be sympathetic landlords purely on account of their ecclesiastical position, and when their tenants appeared before the abbot's manorial court, they were not appearing before an abbot, but before a judge, and the usual strictures of common law would apply.[32] The monks may have been strict or oppressive landlords and the people responded fiercely against what historian Richard Hilton has labelled a form of "social degradation."[33] If the abbey was as poor as has been assumed, then this may account for the monks having to be extra harsh landlords;[34] they would appear to have undertaken their landlordly duties with zeal,[35] Ultimately though, it is impossible to be certain as to whether the abbey was as locally tyrannous as the villagers claimed. It is also possible that previous earls of Chester had been lax in their enforcement of serfdom, and that the two villages had got used to their relative freedoms. It is also possible that it was the monks who had been too lax in their enforcement, and that the villagers of Darnhall and surrounding areas saw an opportunity to take advantage of them.[36]

The villagers prosecuted their struggle in earnest, sometimes going to law, sometimes resorting to violence.[37][24] The people of the area attacked monastic officials on many occasions: In 1320, during the abbacy of Richard of Evesham, one of the monks was attacked (and a servant killed) while collecting tithes in Darnhall,[25] and in 1339, the abbot himself was slain defending his house's prerogatives.[38]

Relations with the gentry were no better and they too often came to blows with the monks. The abbey was involved in feuds with a number of the prominent local families and these frequently ended in large-scale violence.[38] Throughout the 14th and 15th centuries Vale Royal was often beset by scandal of other kinds too. Many of the abbots proved to be incompetent, venal, or even criminally inclined;[note 10] the house was frequently grossly mismanaged. As time went on discipline became lax and in the 14th and early 15th century there was much disorder at the abbey, with reports of serious crimes including attempted murder being committed by Vale Royal monks. Another abbot, Henry Arrowsmith, a man with a reputation for lawlessness, was hacked to death in 1437 by a group of men including the vicar of Over. This abbot was slain in revenge for a rape he was alleged to have committed. The abbey was taken under royal supervision in 1439, but there was no immediate improvement. In the 1450s the scandalous doings of the monks of Vale Royal attracted the attention of the government and even the General Chapter, the international governing body of the Cistercian order. In 1455 they ordered senior abbots to investigate the abbey, which they described as "damnable and sinister". Thereafter things improved somewhat and the last years of Vale Royal were fairly peaceful and well ordered.[4]

Dissolution

In 1535 the abbey was valued in the Valor Ecclesiasticus as having an income of £540. This figure meant that Vale Royal escaped being dissolved under the terms of the First Suppression Act, King Henry VIII's initial move in the Dissolution of the Monasteries. The last abbot was John Hareware (elected 1535), who had previously been abbot of Hulton abbey. He pursued a two-pronged policy of attempting to ensure the survival of his abbey and, should that fail, the security of himself and his brethren thereafter. Hareware bribed courtiers, influential nobles and in particular chief minister Thomas Cromwell with money and property in an attempt to gain respite for his Abbey. He also leased out most of the abbey lands to friends and associates of the monastery to keep them out of royal hands should the abbey fall (many of these leases had a clause which stated that they should be void if the abbey survived). He began to realise the other assets such as livestock and timber for cash.[4]

The process of dissolution at Vale Royal was begun in September 1538 by Thomas Holcroft, one of the king's commissioners, and occurred in very shady circumstances. Holcroft claimed that the abbey had surrendered to him on 7 September. The abbot and convent strongly denied that they had done so and questioned Holcroft's authority. To defend himself, Holcroft then alleged that the abbot had attempted to take over the abbey for himself and had tried to conspire with Holcroft to engage in land fraud involving the abbey estates.[4] The Vale Royal monks petitioned the government, in particular, Thomas Cromwell who, in his role as Vicar General was in charge of church affairs under the Royal Supremacy. Abbot John appealed to Cromwell in person and in the course of his journey to London to see the chief minister wrote to him:

My Good Lord, the truth is, I nor my said brethren have never consented to surrender our monastery not yet do, nor never will by our good wills unless it shall please the King's grace to give us commandment to do so.

There must have been some disquiet in governmental circles as to whether the surrender of Vale Royal was, in fact, legitimate, so steps were taken to put the matter beyond doubt. A special court was held at the abbey on 31 March 1539, with Cromwell himself as judge. However, instead of investigating the circumstances of the surrender, the court charged the abbot with treason and the murder of a monk who had committed suicide in 1536, serious crimes that would have earned the death penalty. The abbot was found guilty, and Vale Royal was declared forfeit to the crown because of his crimes.[39] Abbot John was not executed. Instead, he was given the substantial pension of £60 per year and the abbey's plate, indicating that the trial was a method of putting pressure on him to acquiesce to the wishes of Cromwell and Holcroft regarding the fate of his monastery.[4][39] The rest of the community were also pensioned off. Pension records indicate that Abbot John lived until at least 1546.[4]

Later history

After these transactions Thomas Holcroft was now in charge at Vale Royal. In 1539 he demolished the church, telling King Henry in a letter that it was "plucked down".[16] On 7 March 1544 the king confirmed Holcroft's ownership by granting him the abbey and a lot of its estates for the sum of £450.[16][40] Holcroft then took down many of the abbey's domestic buildings, retaining the south and west cloister ranges including the abbot's house and the monks' dining hall along with their kitchen as the core of his very large mansion on the site.[16]

Holcroft's heirs lived at Vale Royal until 1615, when the abbey came into the hands of the Cholmondeley (pronounced "Chumley") family (subsequently Lords Delamere).[41] The widowed Lady Mary Cholmondeley (1562–1625), a powerful woman with extensive properties in the area, bought the abbey as a home for herself when her eldest son inherited the primary family estates at Cholmondeley. In August 1617 she entertained James I to a stag hunting party at Vale Royal.[39] The king enjoyed himself so much that he gave knighthoods to two members of the family. Shortly afterwards, in a letter, he offered to advance the political careers of Lady Mary's sons if they would come to court. This offer was so firmly refused that the king named her "the Bolde Lady of Cheshire".[42] At her death in 1625 Lady Mary passed the abbey and estate on to her fourth son, Thomas, who founded the Vale Royal branch of the family.[43]

During the English Civil War the Cholmondeleys were supporters of Charles I.[43] Their allegiance had serious consequences: there was fighting at Vale Royal, the abbey was extensively looted and the south wing of the building burned down by Parliamentarian forces under the command of General John Lambert.[44]

Following this disaster, the Cholmondeley family continued to live in the abbey. In 1833 a new southeast wing, designed by Edward Blore, was added to the building. In 1860, Hugh Cholmondeley, 2nd Baron Delamere, commissioned the Chester architect John Douglas to recast the centre of the south range, which had formerly been timber-framed. The following year Douglas added a southwest wing, and in so doing, altered the dining room.[45] Opposite the west lodge of the abbey stands the church of St Mary, the capella extra portis (chapel without the gates) of the abbey. This had been largely rebuilt in 1728, incorporating fabric from a timber-framed church dating probably from the 14th century. In 1874–75 Douglas re-modelled the church, changing its external appearance, but again retaining much of the internal fabric.[46]

The Cholmondeley family lived in the abbey until 1907, when Vale Royal was rented out to Robert Dempster, a wealthy businessman from Manchester.[47] Robert Dempster had made his fortune from the gas engineering company he founded, R & J Dempster and Sons in 1883. In that year his second daughter Edith (Edith Pretty) was born but he was never to have sons. Edith continued to live at Vale Royal with her father until his death in 1925 in South Africa. He was buried at Whitegate Church close to Vale Royal. Edith inherited half of his fortune and all of his personal effects, including the lease on Vale Royal. In the spring of 1926, Edith married a long-time suitor Frank Pretty, again at Whitegate Church. She gave up the lease on Vale Royal and purchased the relatively modest Sutton Hoo estate later that year. Frank died at the end of 1934 and in 1939 Edith Pretty engaged a 'jobbing' archaeologist Basil Brown to excavate some of the mounds on the Sutton Hoo estate, discovering the richest Anglo-Saxon burial in Northern Europe.[48]

In 1934, another Cholmondeley, Thomas, 4th Baron Delamere, moved into the abbey, only to be forced out in 1939 when the government took over Vale Royal to serve as a sanatorium for soldiers of World War II.[47] The Cholmondeleys regained possession of the abbey after the war, but in 1947 they sold it, at which point Vale Royal began to experience many vicissitudes.[49]

Vale Royal was purchased by ICI in 1947.[47] The chemical company initially used the abbey as staff accommodation and then, from 1954 to 1961, as the headquarters for its Alkali Division. ICI moved out in 1961, and for some years the future of Vale Royal was in doubt. There were abortive schemes to use the abbey as a health centre, a country club, a school and even a prison (this latter proposal was resisted by local inhabitants as strongly, though less violently, as the original foundation of the abbey had been, and did not occur). In 1977, the abbey was made into a residential care home for people with learning difficulties.[50] Since 1998, Vale Royal has been home to a private golf club.[51]

Remains

Nothing remains of the great church, though archaeological work has revealed many details of its structure.[1] Early 20th-century excavations established that the church was 421 feet (128 m) long, with a decoratively floored 92-foot (28 m) nave. The width of the east and west transepts together was 232 feet (71 m).[10] The rest of the construction was, at various times in its career, built around a grassed quadrangle (possibly also serving as a herb garden),140 feet (43 m) square. These consisted, apart from the church (which took up the east side of the square), of a chapter house,[note 11] the abbot's dwelling, accommodation for guests, and various outbuildings necessary for the domestic upkeep of the community and its agricultural work.[54]

A circular stone monument, known as the 'Nun's Grave', traditionally commemorates a 14th-century Cheshire nun, Ida, who tended a sick Vale Royal abbot, and on her death was buried at the site of the high altar.[10] The monument was erected by the Cholmondeley family, possibly to lend credence to the legend of the nun. The material in its construction comes from three sources: the head made from a medieval cross with four panels depicting the Crucifixion, the Virgin and Child, St. Catherine, and St. Nicholas; the shaft, made of sandstone in the 17th century; and a plinth made from reclaimed abbey masonry.[55] The present country house on the site incorporates substantial parts of the south and west ranges of the abbey plus Holcroft's Tudor house. It is a Grade II* listed building,[3] and St Mary's church is listed at Grade II.[56]

Notes

- ↑ It has also been suggested that the original site was uncomfortably distant from a fresh water source sufficient to provide for a large community: Darnhall was on the bank of the Ash Brook, but this was a minor waterway. Whereas Vale Royal was sited next to the River Weaver, which had two equally powerful [[|feeder river]]s nearby.[7]

- ↑ Alphonso was King Edward's and Eleanor of Castile eighth child but, by 1277, their only surviving son; he was, therefore, at this time, heir to the throne.[8]

- ↑ This retinue included the Earls of Gloucester, Cornwall, Surrey, and Warwick, Maurice de Craon, Otto de Grandson and Robert de Vere[4]

- ↑ Hospitality was a primary duty for those under Benedictine rule, such as the Cistercians, for St Benedict instructed "let all guests be received as Christ himself."[13] Yet, "the cost of entertaining guests on ceremonial occasions hosted by the community was considerable."[14]

- ↑ The abbey had experienced financial problems since its foundation, and although it had been granted a licence in 1275 to sell wool to pay for its building works, seven years' later the abbey owed £172 to merchants, By 1311, £200 was still owed to one of the custodians of the works from 1284.[4]

- ↑ This became common practice from the 14th century onwards. It was a convenient device for alleviating a religious house of its debts: The reign of Edward III, notes historian F. R. Lewis, saw 539 such instances.[19]

- ↑ The extent to which this even concerned the monks-particularly in the early years-has been questioned. Cistercians, it has been noted, "were not normally too bothered by that as they had a reputation as de-populators and often uprooted whole communities."[11]

- ↑ In the early-medieval period, villeins were serfs who were tied to the land they worked, and as bonded tenants, they could not leave or stop working that land without the agreement of the lord of the manor. By the late 14th century the role had ceased being as burdensome as it would have been a couple of hundred years earlier, with no heavy labouring service enforced. But it was still possible (and Vale Royal Abbey was party to this) for a lord to insist on receiving a third of a tenant's goods on the latter's death.[26] Also, not being freemen, villeins did not have recourse to trial by jury.[27][28][29] Even so: "despite the light labour services associated with villein tenure, there is no doubt that the personal and financial liabilities could weigh heavily."[30] One particular service the villages of both Darnhall and Over were contracted for was that when a daughter married, "redemption" had to be paid to the abbey.[31]

- ↑ This involved the right to clear forest land for agricultural purposes, and to remove timber and branches.[24]

- ↑ For example, Abbot Stephen (in office 1373-c. 1400) was involved in violent fighting with the Bulkeley family of Cheadle in 1375; in 1394, he gave sanctuary to a convicted murderer; he was regularly accused of preventing the arrest or prosecution of his own monks; he took bribes to allow prisoners to escape; he illegally felled forestry and profited from it; and in 1395 a commission discovered that he had spent the previous decade greatly impoverishing the abbey by selling, alienating, and generally destroying its estates. Further, during his abbacy, two of his own monks were accused respectively of theft and of rape.[4]

- ↑ The Chapter house has been described as "a place second in importance to the church itself," and was where the main business of the abbey took place, both religious (being where the monks read chapters of St Benedict's teachings, giving the building its name, and, peculiar to this order, Cistercian monks made public confession to each other here)[52] and especially administrative[53] (the manorial court was held there, for example).[11]

See also

References

- 1 2 Historic England & 72883.

- ↑ Historic England & 1016862.

- 1 2 Historic England & 1160862.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 V. C. H. 1980, pp. 156–165.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Robinson et al. 1998, p. 192.

- 1 2 Brownbill 1914, p. vi.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Bostock & Hogg 1999, p. 1.

- ↑ Prestwich 1988, p. 126.

- ↑ Powicke 1991, p. 412.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Bostock & Hogg 1999, p. 2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Bostock & Hogg 1999, p. 3.

- ↑ Bell, Brooks & Dryburgh 2007, p. 28.

- ↑ Kerr 2008, p. 25.

- ↑ Kerr 2007, p. 188.

- ↑ Donnelly 1954, p. 443.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Robinson et al. 1998, p. 193.

- ↑ Platt 1994, p. 65.

- ↑ Prestwich 2003, p. 35.

- ↑ Lewis 1938, pp. 24–25.

- ↑ Lewis 1938, p. 25.

- ↑ Colvin 1963, p. 256.

- 1 2 3 Midmer 1979, p. 315.

- ↑ V. C. H. 1980, pp. 1156–165.

- 1 2 3 Bostock & Hogg 1999, p. 5.

- 1 2 3 Hewitt 1929, p. 166.

- ↑ Bennett 1983, p. 92.

- ↑ Harding 1993, pp. 74–76.

- ↑ Faith 1999, pp. 245–265.

- ↑ Hatcher 1987, pp. 247–284.

- ↑ Booth 1981, pp. 4–5.

- ↑ C. C. C. 1967, p. 89.

- ↑ Hewitt 1929, p. 168.

- ↑ Hilton 1949, p. 128.

- ↑ Firth-Green 1999, p. 166.

- ↑ Morgan 1987, p. 77.

- ↑ Brownbill 1914, p. 186.

- ↑ Hilton 1949, p. 161.

- 1 2 Heale 2016, p. 260.

- 1 2 3 Holland et al. 1977, p. 19.

- ↑ Holland et al. 1977, p. 37.

- ↑ Holland et al. 1977, p. 20.

- ↑ Holland et al. 1977, p. 21.

- 1 2 Holland et al. 1977, p. 22.

- ↑ Holland et al. 1977, p. 23.

- ↑ Hubbard 1991, p. 40.

- ↑ Hubbard 1991, p. 124.

- 1 2 3 Holland et al. 1977, p. 32.

- ↑ Skelcher & Durrant 2008, pp. 54–55.

- ↑ Holland et al. 1977, pp. 25, 32.

- ↑ Holland et al. 1977, p. 25.

- ↑ V. R. A. 2008.

- ↑ Stalley 1999, p. 188.

- ↑ Hamlett 2013, p. 117.

- ↑ Bostock & Hogg 1999, p. 4.

- ↑ Latham 1993, p. 127.

- ↑ Historic England & 1160911.

Bibliography

- Bell, A. R.; Brooks, C.; Dryburgh, P. R. (2007). The English Wool Market, c.1230–1327. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-46780-3.

- Bennett, M. J. (1983). Community, Class and Careers. Cambridge Studies in Medieval Life and Thought. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-52182-6.

- Booth, P. H. W. (1981). The Financial Administration of the Lordship and County of Chester, 1272-1377. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-1337-9.

- Bostock, A. J.; Hogg, S. M. (1999). Vale Royal Abbey and the Cistercians 1277-1538. Northwich: Northwich & District Heritage Society. OCLC 50667863.

- Brownbill, J., ed. (1914). The Ledger Book of Vale Royal Abbey. Manchester: Manchester Record Society.

- C. C. C. (1967). A History of Cheshire. V. Chester: Cheshire Community Council.

- Colvin, H. (1963). The History of the King's Works. Ministry of Public Building and Works. I. London: H.M. Stationery Office.

- Donnelly, J. (1954). "Changes in the Grange Economy of English and Welsh Cistercian Abbeys, 1300-1540". Traditio. 10: 399–458. OCLC 557091886.

- Faith, R. (1999). The English Peasantry and the Growth of Lordship. London: Leicester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7185-0204-1.

- Firth-Green, R. (1999). A Crisis of Truth: Literature and Law in Ricardian England. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-8122-18094.

- Hamlett, L. (2013). "The Twin Sacristy Arrangements in Palladio's Venice: Origns and Adaptions". In Avcioglu, N.; Jones, E. Architecture, Art and Identity in Venice and its Territories, 1450-1750: Essays in Honour of Deborah Howard. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-351-575959.

- Harding, A. (1993). England in the Thirteenth Century. Oxford: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-31612-5.

- Hatcher, J. (1987). "English Serfdom and Villeinage: Towards a Reassessment". In T. H. Aston. Landlords, Peasants and Politics in Medieval England. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-03127-1.

- Heale, M. (2016). The Abbots and Priors of Late Medieval and Reformation England. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-870253-5.

- Hewitt, H. J. (1929). Mediaeval Cheshire: An Economic and Social History of Cheshire in the Reigns of the Three Edwards. Manchester: Manchester University Press. pp. 111–. GGKEY:RZPQ52YFGDW.

- Hilton, R. H (1949). "Peasant Movements in England before 1381". The Economic History Review. New Series. 2. OCLC 47075644.

- Historic England, "Vale Royal Abbey (1016862)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 5 September 2012

- Historic England, "Vale Royal Abbey (1160862)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 5 September 2012

- Historic England, "Vale Royal Abbey (72883)", PastScape, retrieved 5 September 2012

- Historic England, "Church of St Mary, Whitegate and Marton (1160911)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 5 September 2012

- Holland, G. D.; Hickson, J. N.; Vose, R. Hurst; Challinor, J. E. (1977), Vale Royal Abbey and House, Winsford Local History Society

- Hubbard, Edward (1991), The Work of John Douglas, The Victorian Society, ISBN 0-901657-16-6

- Kerr, J. (2007). Monastic Hospitality: The Benedictines in England, C.1070-c.1250. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-326-0.

- Kerr (2008). "Cistercian Hospitality in the Later Middle Ages". In Burton, J. E.; Stöber, K. Monasteries and Society in the British Isles in the Later Middle Ages. Woodbrige: Boydell & Brewer Ltd. pp. 25–39. ISBN 978-1-84383-386-4.

- Latham, F. A., ed. (1993), Vale Royal, Whitchurch, Shropshire: The Local History Group, OCLC 29636689

- Lewis, F. R. (1938). "The History of Llanbadarn Fawr, Cardiganshire, in the Later Middle Ages". Transactions and archaeological record of the Cardiganshire Antiquarian Society. 12. OCLC 690106742.

- Midmer, R. (1979). English Medieval Monasteries 1066 - 1540. London: Heineman. ISBN 0434465356.

- Platt, C. (1994). Medieval England: A Social History and Archaeology from the Conquest to 1600 AD. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-12913-8.

- Morgan, P. (1987). War and Society in Medieval Cheshire, 1277-1403. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-13423.

- Powicke, F. M. (1991). The Thirteenth Century, 1216-1307 (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford. ISBN 0192852493.

- Prestwich, M. (1988). Edward I. Yale English Monarchs. London: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-06266-5.

- Prestwich, M. (2003). The Three Edwards: War and State in England 1272–1377. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-41311-9.

- Robinson, David; Burton, Janet; Coldstream, Nicola; Coppack, Glyn; Fawcett, Richard (1998), The Cistercian Abbeys of Britain, Batsford, ISBN 978-0-7134-8392-5

- Skelcher, M.; Durrant, C. (2008), Edith Pretty: From Socialite to Sutton Hoo, Leiston Press, ISBN 0-9554725-0-4

- Stalley, R. A. (1999). Early Medieval Architecture. Oxford History of Art. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-2842237.

- V. C. H. (1980). Elrington, C. R.; Harris, B. E., eds. Houses of Cistercian monks: The abbey of Vale Royal. A History of the County of Chester. Victoria County History. 3. University of London & History of Parliament Trust.

|access-date=requires|url=(help) - V. R. A., ed. (2008). "Vale Royal Abbey Golf Club".

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Vale Royal Abbey. |

- Information on the abbey from the Sheffield University site about Cistercian abbeys in the UK

- The Ledger Book of Vale Royal abbey: the main record book of the abbey. First published by the Record Society of Lancashire and Cheshire in 1914 – full-text version as part of British History Online

- Information about the stained glass from the Corpus Vitrearum Medii Aevi (CVMA) of Great Britain