Utahraptor

| Utahraptor | |

|---|---|

| |

| Hind leg | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Order: | Saurischia |

| Suborder: | Theropoda |

| Family: | †Dromaeosauridae |

| Subfamily: | †Dromaeosaurinae |

| Genus: | †Utahraptor Kirkland, Gaston & Burge, 1993 |

| Type species | |

| †Utahraptor ostrommaysorum Kirkland et al, 1993 | |

Utahraptor (meaning "Utah's predator"[1] or "Utah's thief"[2]) is a genus of theropod dinosaurs. It contains a single species, Utahraptor ostrommaysorum, which is the largest-known member of the family Dromaeosauridae. Fossil specimens date to the upper Barremian stage of the early Cretaceous period (in rock strata dated to 126 ± 2.5 million years ago).[3]

In 2018, it was proposed that Utahraptor be the Utah state dinosaur, an act that was approved by the Senate.[4] Initially Utahraptor would have replaced another dinosaur, the Allosaurus, as the state's official fossil, but it was decided that Utahraptor would be another symbol of the state.[5]

Description

The holotype specimen of Utahraptor is fragmentary, consisting of skull fragments, a tibia, claws and some caudal (tail) vertebrae. These few elements suggest an animal about twice the length of Deinonychus.[1] Like other dromaeosaurids, Utahraptor had large curved claws on their second toes. One claw specimen is preserved at 22 centimeters (8.7 in) in length and is thought to reach 24 cm (9.4 in) restored.

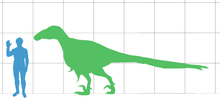

The largest described U. ostrommaysorum specimens are estimated to have reached up to 5.7 meters (19 ft) long and somewhat less than 500 kilograms (1,100 lb) in weight, comparable to a grizzly bear or polar bear in size.[1][2] However, the 2001 Kirkland discovery indicates the species may be far heavier than previously estimated.[6]

It is thought that Utahraptor is closely related to the smaller Dromaeosaurus and the giant Mongolian and North American dromaeosaurid genera Achillobator and Dakotaraptor, based on cladistic analysis.[1][7][8]

Although feathers have never been found in association with Utahraptor specimens, there is strong phylogenetic evidence suggesting that all dromaeosaurids possessed them. This evidence comes from phylogenetic bracketing, which allows paleontologists to infer traits that exist in a clade based on the existence of that trait in a more basal form. The genus Microraptor is one of the oldest-known dromaeosaurids, and is phylogenetically more primitive than Utahraptor.[9] Since Microraptor and other dromaeosaurids possessed feathers, it is reasonable to assume that this trait was present in all of Dromaeosauridae. Feathers were very unlikely to have evolved more than once, so assuming that any given dromaeosaurid, such as Utahraptor, lacked feathers would require positive evidence that they did not have them.[10] So far, there is nothing to suggest that feathers were lost in larger, more derived species of dromaeosaurs.[11]

In a 2001 study conducted by Bruce Rothschild and other paleontologists, two foot bones referred to Utahraptor were examined for signs of stress fracture, but none were found.[12]

Discovery

The first specimens of Utahraptor were found in 1975 by Jim Jensen in the Dalton Wells Quarry in east-central Utah, near the town of Moab, but did not receive much attention. After a find of a large foot-claw by Carl Limoni in October 1991, James Kirkland, Robert Gaston, and Donald Burge uncovered further remains of Utahraptor in 1991 in the Gaston Quarry in Grand County, Utah, within the Yellow Cat and Poison Strip members of the Cedar Mountain Formation.[1] Radiometric dating has shown that these parts of the Cedar Mountain Formation were deposited about 124 million years ago.[13] The type specimen, CEU 184v.86, is currently housed at the College of Eastern Utah Prehistoric Museum, although Brigham Young University, the depository of Jensen's finds, currently houses the largest collection of Utahraptor fossils.

The type species (and only known species of Utahraptor), Utahraptor ostrommaysorum, was named by Kirkland, Gaston, and Burge in June 1993 for the American paleontologist John Ostrom from Yale University's Peabody Museum of Natural History, and Chris Mays of Dinamation International. Originally, in the specific name, the singular genitive ostrommaysi was used but, in 2000, this was emended by George Olshevsky to the plural.[14] Earlier, it had been intended to name the species "Utahraptor spielbergi" after film director Steven Spielberg, in exchange for funding paleontological research, but no agreement could be reached on the amount of financial assistance.[15]

In 2001, Kirkland et al, pursued a graduate student's discovery of a bone protruding from a 9-ton fossil block of sandstone in eastern Utah. It was determined to contain the bones of at least seven individuals, including an adult measuring about 4.8 m (16 ft), four juveniles and a hatchling about 1 m (3.3 ft) long. Also fossilized with the predators are the remains of at least one possible iguanodont herbivore.[16][17]

Kirkland speculated that the Utahraptors attempted to scavenge carrion or attack helpless prey mired in quicksand, and were themselves mired in the attempt to attack the herbivore. Similar sites such as the Cleveland-Lloyd Quarry and California's La Brea Tar Pits house such predator traps. Examination of the fossils are ongoing after a decade of excavation, but if Kirkland is correct, it may be one of the best preserved predator traps ever discovered. The fossils may further reveal aspects into the behavior of Utahraptor, such as whether it might have hunted in groups like Deinonychus is believed to have done.[18] Whether all the Utahraptor individuals were mired simultaneously or were drawn in, one-by-one, is unclear, as work is currently slowed on the specimens. More concrete answers may yet come to light once crowdfunding efforts to employ professional excavator, Utahraptor Project leader Scott Madsen, are completed.[6]

Classification

Utahraptor is a member of the family Dromaeosauridae, a clade of theropod dinosaurs commonly known as "raptors". Utahraptor is the largest genus in the family, and belongs to the same clade as some famous dinosaurs such as Velociraptor, Deinonychus or Dromaeosaurus. Utahraptor is classified in the subfamily Dromaeosaurinae, which is found in the clade Eudromaeosauria.

Below is a cladogram by Senter et al. in 2012.[19]

| Eudromaeosauria |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleobiology

According to the authors of its description, Utahraptor had an "important [ecological] role as a major carnivore of the fauna of the present-day Arks region in the early Cretaceous", and could probably attack prey larger than itself. Group hunting of individuals of at least 3.5 m and 70 kg, if proven, could have killed 8 m prey of a weight of one to two tonnes[1]. According to paleontologist Gregory S. Paul, Utahraptor was not particularly fast and would have been an ambush hunter that preyed on large dinosaurs such as the contemporary iguanodontians and therizinosauroids it shared its environment with. Its robust build and large sickle claw indicates it was well suited to hunting such prey. Like other dromaeosaurine dromaeosaurids, it may have also relied heavily on its jaws to dispatch prey more than other types of dromaeosaurids such as those in the velociraptorinae.[20]

Paleoecology

Utahraptor lived in the lower part of the Cedar Mountain Formation, which during the Barremian was a semiarid area with floodplain prairies, riverine forests, and open woodlands. There is believed to have been a short wet season. Other fauna that were contemporaneous with the dromaeosaurid in the Yellow Cat and Poison Strip Members included the therizinosauroids Falcarius and Martharaptor, the sauropods Cedarosaurus, Mierasaurus, Venenosaurus and Moabosaurus, the iguanodonts Iguanocolossus, Planicoxa, Cedrorestes and Hippodraco, the hadrosauroid Eolambia, and the ankylosaur Gastonia. Fellow dromaeosaurid Yurgovuchia, the troodontid Geminiraptor and the ornithomimosaur Nedcolbertia also dwelled here. Birds, fish, mammals, turtles, crocodiles, and pterosaurs are also known from the formation, creating a diverse fauna. [21]

In popular culture

A speculative reconstruction of Utahraptor's way of life and behavior was presented in the 1999 BBC TV series Walking with Dinosaurs.[22] The program represented Utahraptor with several inaccuracies, including hands in pronation, lack of feathers and located in Europe although all the Utahraptor fossils have been found in, as its name says, Utah.[23]

It is also depicted in the same wrong way in the History Channel series Jurassic Fight Club, battling with the ankylosaur Gastonia. A scientifically more accurate reconstruction of Utahraptor appeared in the 2011 Discovery Channel Dinosaur Revolution program.[24]

Raptor Red was published in 1995, and features the fictionalized story of a female Utahraptor. Written by paleontologist Robert T. Bakker, it was positively regarded by mainstream reviewers, though updates to the science have rendered some of the story line facts presented untrue and the paleontology community was critical of fossil record inaccuracies.[25][26] Bakker's anthropomorphisis of the titular Red was particularly praised.[27][28][29]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Utahraptor. |

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Kirkland, J.I.; Burge, D.; Gaston, R. (1993). "A large dromaeosaur [Theropoda] from the Lower Cretaceous of Utah". Hunteria. 2 (10): 1–16.

- 1 2 Holtz, Thomas R. Jr. (2008) Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages Supplementary Information

- ↑ Kirkland, J.I. and Madsen, S.K. (2007). "The Lower Cretaceous Cedar Mountain Formation, eastern Utah: the view up an always interesting learning curve." Fieldtrip Guidebook, Geological Society of America, Rocky Mountain Section. 1-108 p.

- ↑ Nicole Nixon (February 12, 2018). "Senate Gives Utahraptor A Roar Of Approval". Retrieved February 13, 2018.

- ↑ Lisa Riley Roche (February 12, 2018). "Senate approves bill making Utahraptor state dinosaur". Retrieved February 18, 2018.

- 1 2 Switek, Brian (September 28, 2016). "Ancient fossils reveal a sticky dinosaur death trap". Washington Post. Retrieved April 15, 2017.

- ↑ Turner, Alan H.; Pol, D.; Clarke, J.A.; Erickson, G.M.; Norell, M. (2007). "A basal dromaeosaurid and size evolution preceding avian flight". Science. 317 (5843): 1378–1381. doi:10.1126/science.1144066. PMID 17823350.

- ↑ https://kuscholarworks.ku.edu/handle/1808/18764

- ↑ Xu, X.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, X.; Kuang, X.; Zhang, F.; Du, X. (2003). "Four-winged dinosaurs from China". Nature. 421 (6921): 335–340. doi:10.1038/nature01342. PMID 12540892.

- ↑ Prum, R.; Brush, A.H. (2002). "The evolutionary origin and diversification of feathers". The Quarterly Review of Biology. 77 (3): 261–295. doi:10.1086/341993. PMID 12365352.

- ↑ Turner, AH; Makovicky, PJ; Norell, MA (2007). "Feather quill knobs in the dinosaur Velociraptor". Science. 317 (5845): 1721. doi:10.1126/science.1145076. PMID 17885130.

- ↑ Rothschild, B., Tanke, D. H., and Ford, T. L., 2001, Theropod stress fractures and tendon avulsions as a clue to activity: In: Mesozoic Vertebrate Life, edited by Tanke, D. H., and Carpenter, K., Indiana University Press, p. 331-336.

- ↑ McDonald, AT, Kirkland JI, DeBlieux DD, Madsen SK, Cavin J, et al. (2010). Farke AA, ed. "New Basal Iguanodonts from the Cedar Mountain Formation of Utah and the Evolution of Thumb-Spiked Dinosaurs". PLoS ONE. 5 (11): e14075. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0014075. PMC 2989904. PMID 21124919.

- ↑ Olshevsky, G., 2000, An annotated checklist of dinosaur species by continent. Mesozoic Meanderings 3: 1-157

- ↑ Adams, Brooke (June 15, 1993). "Director Loses Utahraptor Name Game". Deseret News. Retrieved April 15, 2017.

- ↑ Project looks to draw real picture of ancient creature, Jackson Hole News & Guide, Adam Fondren, September 11, 2017. Retrieved September 10, 2017.

- ↑ James I. Kirkland, Edward L. Simpson, Donald D. DeBlieux, Scott K. Madsen, Emily Bogner & Neil E. Tibert (2016). Depositional constraints on the Lower Cretaceous Stikes Quarry dinosaur site: Upper Yellow Cat Member, Cedar Mountain Formation, Utah. Palaios 31(9): 421-439; doi: 10.2110/palo.2016.041

- ↑ Switek, Brian (January 7, 2015). "Utah's Dinosaur 'Death Trap' Reveals Trove of Giant Predators". National Geographic. Retrieved April 15, 2017.

- ↑ Senter, P.; Kirkland, J.I.; Deblieux, D. D.; Madsen, S.; Toth, N. (2012). Dodson, Peter, ed. "New Dromaeosaurids (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Lower Cretaceous of Utah, and the Evolution of the Dromaeosaurid Tail". PLoS ONE. 7 (5): e36790. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0036790. PMC 3352940. PMID 22615813.

- ↑ Paul, Gregory S. (2016). The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs (2nd Edition). Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. p. 151. ISBN 9780691167664.

- ↑ Paul, Gregory S. (2016). The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs (2nd Edition). Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. pp. 151, 163, 229, 252, 314, 319, 326, 327. ISBN 9780691167664.

- ↑ "Unnatural history? Deconstructing the Walking with Dinosaurs phenomenon." Media Culture & Society, 25 (3): 315-332. doi:10.1177/0163443703025003002

- ↑ Haines, T. (2000). Walking with Dinosaurs: A Natural History. London: BBC Publishing.

- ↑ "Dinosaur Revolution Episode Guide". Discovery Channel. Archived from the original on September 26, 2011. Retrieved September 15, 2011.

- ↑ Holtz, Thomas R. (September 12, 1995). "Raptor Red: a review (long)". Archives of the DINOSAUR Mailing List. Retrieved December 5, 2014.

- ↑ Kanipe, Jeff (February 1996). "Dino Redux". Earth. 5 (1): 66–68.

- ↑ Naughton, John (September 5, 1995). "At home with a Jurassic monster". The Times.

- ↑ Chander, David (November 13, 1995). "In his field, Robert Bakker walks alone". Boston Globe. p. 29.

- ↑ Johnson, Eric (September 1995). "Book Reviews: Fiction". Library Journal. 120 (14): 205.

| Wikinews has related news: Stolen Utahraptor recovered in Australian Capital Territory |