User story

| Software development |

|---|

| Core activities |

| Paradigms and models |

| Methodologies and frameworks |

| Supporting disciplines |

| Practices |

| Tools |

| Standards and Bodies of Knowledge |

| Glossaries |

In software development and product management, a user story is an informal, natural language description of one or more features of a software system. User stories are often written from the perspective of an end user or user of a system. They are often recorded on index cards, on Post-it notes, or in project management software. Depending on the project, user stories may be written by various stakeholders including clients, users, managers or development team members.

User stories are a type of boundary object. They facilitate sensemaking and communication, that is, they help software teams organize their understanding of the system and its context.[1]

User stories are often confused with system requirements. A requirement is a formal description of need; a user story is an informal description of a feature.

History

In 1998 Alistair Cockburn visited the Chrysler C3 project in Detroit and coined the phrase "A user story is a promise for a conversation."[2]

With Extreme Programming (XP),[3] user stories were a part of the planning game.

In 2001, Ron Jeffries proposed a "Three Cs" formula for user story creation:[4]

- The Card (or often a post-it note) is a tangible durable physical token to hold the concepts;

- The Conversation is between the stakeholders (customers, users, developers, testers, etc.). It is verbal and often supplemented by documentation;

- The Confirmation ensures that the objectives of the conversation have been reached.

User stories are written by or for users or customers to influence the functionality of the system being developed. In some teams, the product manager (or product owner in Scrum), is primarily responsible for formulating user stories and organizing them into a product backlog. In other teams, anyone can write a user story. User stories can be developed through discussion with stakeholders, based on personas or simply made up.

Common templates

User stories may follow one of several formats or templates. The most common would be the Connextra template:[5][6]

As a <role> I can <capability>, so that <receive benefit>

Chris Matts suggested that "hunting the value" was the first step in successfully delivering software, and proposed this alternative:[7]

In order to <receive benefit> as a <role>, I can <goal/desire>

Elias Weldemichael, on the other hand, suggested the "so that" clause is perhaps optional although still often helpful:[8]

As a <role>, I can <goal/desire>, so that <why>

Another template based on the Five Ws specifies:

As <who> <when> <where>, I <want> because <why>

Another template based on Rachel Davies' popular template:[9]

As <persona>, I can <what?> so that <why?>

where a persona is a fictional stakeholder (e.g. user). A persona may include a name, picture; characteristics, behaviors, attitudes, and a goal which the product should help them achieve.

Examples

Screening Quiz (Epic Story)

- As the HR manager, I want to create a screening quiz so that I can understand whether I want to send possible recruits to the functional manager.[10]

Quiz Recall

- As a manager, I want to browse my existing quizzes so I can recall what I have in place and figure out if I can just reuse or update an existing quiz for the position I need now.[10]

Limited Backup

- As a user, I can indicate folders not to backup so that my backup drive isn't filled up with things I don't need saved.[11]

Usage

As a central part of many agile development methodologies, such as in XP's planning game, user stories define what has to be built in the software project. User stories are prioritized by the customer (or the product owner in Scrum) to indicate which are most important for the system and will be broken down into tasks and estimated by the developers. One way of estimating is via a Fibonacci scale.

When user stories are about to be implemented, the developers should have the possibility to talk to the customer about it. The short stories may be difficult to interpret, may require some background knowledge or the requirements may have changed since the story was written.

Every user story must at some point have one or more acceptance tests attached, allowing the developer to test when the user story is done and also allowing the customer to validate it. Without a precise formulation of the requirements, prolonged nonconstructive arguments may arise when the product is to be delivered.

Benefits

There is no good evidence that using user stories increases software success or developer productivity. However, user stories facilitate sensemaking without undue problem structuring, which is linked to success.[12]

Limitations

Limitations of user stories include:

Scale-up problem

User stories written on small physical cards are hard to maintain, difficult to scale to large projects and troublesome for geographically distributed teams.

Vague, informal and incomplete

User story cards are regarded as conversation starters. Being informal, they are open to many interpretations. Being brief, they do not state all of the details necessary to implement a feature. Stories are therefore inappropriate for reaching formal agreements or writing legal contracts.[13]

Lack of non-functional requirements

User stories rarely include performance or non-functional requirement details, so non-functional tests (e.g. response time) may be overlooked.

Relationship and Usage of User Stories to Epics, Themes, Initiatives

In many contexts user stories are used and also summarized in groups for semantic and organizational reasons. The different usages depend on the point-of-view, e.g. either looking from a user perspective as product owner in relation to features or a company perspective in relation to task organization.

While some suggest to use 'epic' and 'theme' as labels for any thinkable kind of grouping of user stories, organization management tends to use it for strong structuring and uniting work loads. For instance, Jira, seems to use a hierarchically organized to-do-list, in which they named the first level of to-do-tasks 'user-story', the second level 'epics' ( grouping of user stories ) and the third level 'initiatives' ( grouping of epics ). However, initiatives are not always present in product management development and just add another level of granularity. In Jira, 'themes' exist ( for tracking purposes ) that allow to cross-relate and group items of different parts of the fixed hierarchy. [14] [15] In this usage, Jira, shifts the meaning of themes in an organization perspective: e.g how much time did we spent on developing theme "xyz". But another definition of themes is: a set of big group of stories, epics, features etc for a user that forms a common semantic unit or goal. There is probably not a common definition because different approaches exist for different styles of product design and development. In these sense, some also suggest to not use any kind of hard groups and hierarchies. [16] [17] [18] [19] [20] [21]

Epic

Big stories or multiple user stories that are very closely related are summarized as epics. A common explanation of epics is also: a user story that is too big for a sprint.

Initiative

Multiple epics or stories grouped together hierarchically, mostly known from Jira.

Theme

Multiple epics or stories grouped together by a common theme or semantic relationship.

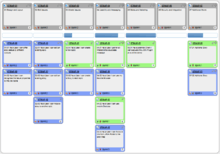

Story map

A story map[22] is a graphical, two-dimensional visualization of the product backlog. At the top of the map are the headings under which stories are grouped, usually referred to as 'epics' (big coarse-grained user stories[23]), 'themes' (collections of related user stories[24]) or 'activities'. These are identified by orienting at the user’s workflow or "the order you'd explain the behavior of the system". Vertically, below the epics, the actual story cards are allocated and ordered by priority. The first horizontal row is a "walking skeleton"[25] and below that represents increasing sophistication.[26]

In this way it becomes possible to describe even big systems without losing the big picture.

Comparing with use cases

A use case has been described as "a generalized description of a set of interactions between the system and one or more actors, where an actor is either a user or another system."[27] While user stories and use cases have some similarities, there are several differences between them.

| User Stories | Use Cases | |

|---|---|---|

| Similarities |

|

|

| Differences |

|

|

| Template | As a <type of user>, I can <some goal> so that <some reason>.[11] |

|

Kent Beck, Alistair Cockburn, Martin Fowler and others discussed this topic further on the c2.com wiki (the home of extreme programming).[29]

See also

References

- ↑ Ralph, Paul (2015). "The Sensemaking-coevolution-implementation theory of software design". Science of Computer Programming. 101: 21–41. arXiv:1302.4061. doi:10.1016/j.scico.2014.11.007.

- ↑ "Origin of story card is a promise for a conversation : Alistair.Cockburn.us". alistair.cockburn.us. Retrieved 2017-08-16.

- ↑ Beck, Kent (1999). "Embracing change with extreme programming". IEEE Computer. 32 (10): 70–77.

- ↑ Ron Jeffries (August 30, 2001). "Essential XP: Card, Conversation, Confirmation".

- ↑ https://www.agilealliance.org/glossary/role-feature/

- ↑ Mishkin Berteig (2014-03-06). "User Stories and Story Splitting". Agile Advice. Retrieved 2017-02-23.

- ↑ AntonyMarcano (2011-03-24). "Old Favourite: Feature Injection User Stories on a Business Value Theme". Antonymarcano.com. Retrieved 2017-02-23.

- ↑ Weldemichael, Weldemichael. "User Story Template Advantages". Mountaingoatsoftware.com. Retrieved 2017-02-23.

- ↑ "10 Tips for Writing Good User Stories". Romanpichler.com. Retrieved 2017-02-23.

- 1 2 Cowan, Alexander. "Your Best Agile User Story". Cowan+. Retrieved 29 April 2016.

- 1 2 Cohn, Mike. "User Stories". Mountain Goat Software. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- ↑ Ralph, Paul; Mohanani, Rahul. "Is Requirements Engineering Inherently Counterproductive?". IEEE. doi:10.1109/TwinPeaks.2015.12.

- ↑ "Limitations of user stories". Ferolen.com. April 15, 2008.

- ↑ https://www.atlassian.com/agile/project-management/epics-stories-themes

- ↑ https://www.atlassian.com/agile/project-management/user-stories

- ↑ https://thedigitalbusinessanalyst.co.uk/epics-stories-themes-and-features-4637712cff5c

- ↑ https://www.mountaingoatsoftware.com/blog/stories-epics-and-themes

- ↑ https://www.scrumalliance.org/community/articles/2014/march/stories-versus-themes-versus-epics

- ↑ https://const.fr/blog/agile/scrum-differences-epics-stories-themes-features/

- ↑ https://www.scrumakademie.de/product-owner/wissen/user-stories-epics-themes/

- ↑ https://www.mountaingoatsoftware.com/blog/you-dont-need-a-complicated-story-hierarchy

- ↑ Patton, Jeff. "The new user story backlog is a map". Retrieved 17 May 2017.

- ↑ Pichler, Roman. "10 Tips for Writing Good User Stories". Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ↑ Cohn, Mike. "User Stories, Epics and Themes". Mountaingoatsoftware.com. Retrieved 26 September 2017.

- ↑ Cockburn, Alistair. "Walking Skeleton". Retrieved 4 March 2013.

- ↑ "Story Mapping". Agile Alliance. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- ↑ Cohn, Mike. "Project Advantages of User Stories as Requirements". Mountaingoatsoftware.com. Retrieved 26 September 2017.

- ↑ Martin Fowler (18 August 2003). "UseCasesAndStories". Retrieved 26 September 2017.

- ↑ "', '' + words + '', '". C2.com. Retrieved 26 September 2017.

Further reading

- Daniel H. Steinberg, Daniel W. Palmer, Extreme Software Engineering, Pearson Education, Inc., ISBN 0-13-047381-2.

- Mike Cohn, User Stories Applied, 2004, Addison Wesley, ISBN 0-321-20568-5.

- Mike Cohn, Agile Estimating and Planning, 2006, Prentice Hall, ISBN 0-13-147941-5.

- Business Analyst Time

- Payton Consulting 'How user stories are different from IEEE requirements