Tyne Bridge

| Tyne Bridge | |

|---|---|

Tyne Bridge looking towards the modern Sage Gateshead with the now moved Tuxedo Princess moored below. The banner is advertising the 2006 Great North Run | |

| Coordinates | 54°58′05″N 1°36′22″W / 54.9680°N 1.6060°W |

| OS grid reference | |

| Carries | |

| Crosses | River Tyne |

| Locale | Tyneside |

| Other name(s) | New Tyne Bridge[1] |

| Owner | |

| Maintained by | Newcastle–Gateshead Bridges Joint Committee |

| Heritage status | Grade II* listed[1] |

| Preceded by | Swing Bridge |

| Followed by | Gateshead Millennium Bridge |

| Characteristics | |

| Design | Through arch bridge |

| Material | Steel |

| Pier construction | Cornish granite |

| Total length | 389 m (1,276 ft) |

| Width | 17 m (56 ft) |

| Longest span | 161.8 m (531 ft) |

| Clearance below | 26 m (85 ft) |

| No. of lanes | 4 |

| History | |

| Architect | Robert Burns Dick |

| Designer | Mott, Hay and Anderson |

| Constructed by | Dorman Long and Co. |

| Construction start | August 1925 |

| Construction end | 25 February 1928 |

| Inaugurated |

|

| Statistics | |

| Daily traffic | approx. 70,000 vehicles |

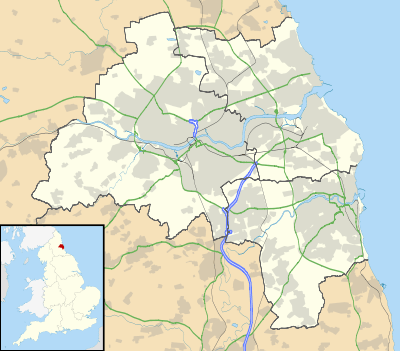

Tyne Bridge Location in Tyne and Wear | |

The Tyne Bridge is a through arch bridge over the River Tyne in North East England, linking Newcastle upon Tyne and Gateshead. The bridge was designed by the engineering firm Mott, Hay and Anderson,[2] who later designed the Forth Road Bridge, and was built by Dorman Long and Co. of Middlesbrough.[3] The bridge was officially opened on 10 October 1928 by King George V and has since become a defining symbol of Tyneside. It is ranked as the tenth tallest structure in the city.

History of construction

The earliest bridge across the Tyne, Pons Aelius, was built by the Romans on the site of the present Swing Bridge around 122.[4]

Work started in August 1925 with Dorman Long acting as the building contractors. Despite the dangers of the building work, only one worker, Nathaniel Collins, a father of four and a local scaffolder from South Shields, died in the building of this structure.[5]

The Tyne Bridge was designed by Mott, Hay and Anderson, comparable to their Sydney Harbour Bridge version.[2][6] These bridges derived their design from the Hell Gate Bridge in New York City.[6] The Dorman Long team was also notable for including Dorothy Buchanan, the first female member of the Institution of Civil Engineers, joining in 1927; in addition to her contribution to the Tyne Bridge, she served as part of the team for the Sydney Harbour Bridge and the Lambeth Bridge in London.[7]

The bridge was completed on 25 February 1928, and officially opened on 10 October by King George V and Queen Mary, who were the first to use the roadway, travelling in their Ascot Landau. The opening ceremony was attended by 20,000 schoolchildren who had been given the day off. Movietone news recorded the speech given by the King.[8]

The Tyne Bridge's towers were built of Cornish granite and were designed by local architect Robert Burns Dick[2] as warehouses with five storeys. But, the inner floors of the warehouses in the bridge's towers were not completed and, as a result, the storage areas were never used. Lifts for passengers and goods were built in the towers to provide access to the Quayside; they are no longer in use.[9]

The bridge's design uses a parabolic arch.[6]

The bridge was originally painted green with special paint made by J. Dampney Co. of Gateshead. The same colours were used to paint the bridge in 2000.[10] The bridge spans 531 feet (162 m) and the road deck is 84 feet (26 m) above the river level.

Technical Information

| Total length | 389 metres (1,276 ft) |

| Length of arch span | 161.8 metres (531 ft) |

| Rise of arch | 55 metres (180 ft) |

| Clearance | 26 metres (85 ft) |

| Height | 59 metres (194 ft) |

| Width | 17.08 metres (56.0 ft) |

| Structural Steel | 7,122 tonnes |

| Total weight of steelwork (arch only) | 3,556 tonnes |

| Total number of rivets (including approaches) | 777,124 |

History of operations

Upon opening, the bridge carried the A1 road. Following the opening of the Tyne Tunnel in 1967, however, the A1 was diverted to the East and the road became the A6127. Following the construction of the Newcastle Western Bypass, the A1 moved again. The bridge was redesignated as the A167, which it remains today.[12] The bridge deck carries 4 lanes of traffic, 2 southbound and 2 northbound, and has a speed limit of 40mph.

In 2012 the largest Olympic rings in the UK were erected on the bridge. The rings were manufactured by commercial signage specialists Signmaster ED Ltd of Kelso. The rings were over 25 metres wide and 12 metres tall and weighed in excess of 4000 kg. This was in preparation for Newcastle hosting the Olympic football tournament, and the Olympic torch relay, in which Bear Grylls zipwired from the top of the arch, to Gateshead quayside.[13]

On 28 June 2012, a large lightning bolt struck the Tyne Bridge. It lit up the roads as the sky was very dark. The bolt, part of a super-cell thunderstorm, came with heavy rain – a month's worth of rainfall in just 2 hours – causing flash flooding on Tyneside.[14]

In 2015 Newcastle upon Tyne was a host city for the Rugby World Cup.[15] Three matches were played at St James Park, the home of Newcastle United Football Club.[16] In recognition, a large illuminated sign was erected on Tyne Bridge.[17]

On 13 November 2017, the Tyne Bridge was the venue for the Freedom on the Tyne finale, the finale of the 2017 Freedom City festival. The 2017 Freedom City festival commemorated Newcastle's civil rights history and the 50 years since Dr Martin Luther King's visit to Newcastle, where King received his honorary degree from Newcastle University.[18][19][20]

Newcastle University and Freedom City 2017 wanted to use the Tyne Bridge to symbolically hark back in history to Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama where King was involved in one of the key moments for the struggle for civil rights in 1965.[18] 24 roads around the Tyne Bridge where closed for the day long event. The Freedom of the Tyne event featured the many civil right stories from history.[18] The final event, revolved around the Jarrow Crusade which was described as a memorable closing to the finale.[18]

Grade II* listed by Historic England

On the 23 August 2018 the bridge became one of the 5.8% of structures in England which are Grade II* listed. The rating means the bridge is a particular important structure of more than special interest.[21] The bridge was upgraded by the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport on the advice of Historic England.[22]

The bridge was upgraded to Grade II* for architectural and historical interest,[1] as outlined here:

Architectural interest:

A striking steel arch design, at its construction, notable as the largest single-span steel arch bridge on the British Isles; It is a similar prototype design as to that prepared for Sydney Harbour, Australia; the main arch was designed by the eminent civil engineer (Sir) Ralph Freeman; the prototype of a method of construction involving progressive cantilevering, using cables, cradles and cranes, which was also developed for Sydney Harbour, but first tested in Newcastle; its neoclassical and Art Deco towers that are well-detailed and defined; a potent symbol of the character and industrial pride of Tyneside; recognised worldwide for its dramatic design.[23]

Historic interest:

it is associated with some of the most distinguished 20th-century civil engineers. One of its engineers being Sir Ralph Freeman, the architect of some of the most impressive bridges in the world. Freeman was a founder of Freeman Fox & Partners, renowned bridge designers worldwide.[23]

Kittiwake colony

The bridge and nearby structures are used as a nesting site by a colony of around 700 pairs of black-legged kittiwakes, the furthest inland in the world. The colony featured in the BBC's Springwatch programme in 2010.[24] Several groups, including the Natural History Society of Northumbria and local Wildlife Trusts, formed a "Tyne Kittiwake Partnership" to safeguard the colony.[25] A proposal for a tower to be built as an alternative nesting site was made in 2011,[26] and in November 2015 a neighbouring hotel submitted a planning application for measures to discourage the birds.[27]

References

- 1 2 3 Historic England. "Tyne Bridge (Grade II*) (1248569)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 2018-09-05.

- 1 2 3 Elwall, Robert. "Tyne Bridge". British Architectural Library. Retrieved 14 July 2014.

- ↑ "Dorman Long Historical Information". dormanlongtechnology.com. Retrieved 14 July 2014.

- ↑ "Pons Aelius - 'The Aelian Bridge'". roman-britain.co.uk. Retrieved 31 October 2017.

- ↑ Butcher, Joanne (1 March 2013). "85 years of the Tyne Bridge". Newcastle Chronicle. Trinity Mirror. Retrieved 14 July 2014.

- 1 2 3 "Tyne Bridge". BBC Inside Out. 24 September 2014. Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- ↑ Chapman, Tegan (10 October 2018). "Female engineers gather to celebrate the Tyne Bridge turning 90". Institution of Civil Engineers. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- ↑ Butcher, Joanne (26 February 2013). "Bridge spans the generations". Newcastle Chronicle. Trinity Mirror. Retrieved 24 November 2014.

- ↑ "The Tyne Bridge". Bridges on the Tyne. 2006. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ↑ Butcher, Joanne (1 March 2013). "85 years of the Tyne Bridge: Crossing of the great divide". Newcastle Chronicle. Trinity Mirror. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- ↑ "Tyne Bridge - Technical Information". structurae.net. International Database for Civil and Structural Engineering. Retrieved 22 May 2017.

- ↑ "A1(M) Central Motorway East". Pathetic Motorways. Retrieved 24 March 2018.

- ↑ "Olympic rings launched on Tyne Bridge". BBC News. BBC. 13 June 2012. Retrieved 16 June 2012.

- ↑ Hough, Andrew (29 June 2012). "Weather: record 110,000 lightning bolts strike during 'superstorms'". Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- ↑ "Host Cities: Newcastle". Rugby World Cup. 2015. Archived from the original on 10 December 2015. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- ↑ "St James' Park". Rugby World Cup. 2015. Archived from the original on 7 December 2015. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- ↑ Davies, Katie (18 February 2015). "Rugby World Cup 2015: Tyne Bridge sign to be replaced with Great North Run advert". Newcastle Chronicle. Trinity Mirror. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 Whetstone, David (4 October 2017). "Newcastle's iconic Tyne Bridge is to host the spectacular Freedom on the Tyne finale". Newcastle Chronicle. Trinity Mirror. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

- ↑ Whetstone, David (13 November 2017). "Statue of Dr Martin Luther King has been unveiled in Newcastle by his great friend". Newcastle Chronicle. Trinity Mirror. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

- ↑ freedomCity2017 Staff. "Freedom City 2017". freedomcity2017.com. Newcastle University. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

- ↑ "Tyne Bridge upgraded to Grade II* by Historic England". BBC News. BBC. 23 August 2018. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

was a "representation of the North East's steely attitude",...; "it fully deserves to be among the 5.8% of structures which are Grade II* listed".

- ↑ Henderson, Tony (23 August 2018). "We all know the Tyne Bridge symbolises greatness - but there's now proof". Newcastle Chronicle. Trinity Mirror. Retrieved 24 August 2018.

- 1 2 "Tyne Bridge listed status upgraded during Great Exhibition Of The North to celebrate its importance". newcastle.gov.uk. Newcastle City Council. 23 August 2018. Retrieved 24 August 2018.

- ↑ "Tynesiders". Springwatch. BBC. 19 May 2010. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- ↑ "Tyne Kittiwakes Partnership". Natural History Society of Northumbria. 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- ↑ Wainwright, Martin (17 May 2011). "Newcastle in a flap over urban kittiwake colony". The Guardian. London: Guardian Media Group. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- ↑ "Installation of bird netting, angled sill plates and avishock system to tower – Tyne Bridge Tower Lombard Street Newcastle upon Tyne". Newcastle City Council. 9 November 2015. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

Further reading

- Addyman, J. and Fawcett, B. The High Level Bridge and Newcastle Central Station: 150 Years Across the Tyne. By the North Eastern Railway Association for the High Level Bridge. 1999. ISBN 1-873513-28-3.

- Linsley, S. Spanning the Tyne: Building of the Tyne Bridge, 1925-28. Newcastle Libraries and Information Service, Newcastle City Council. 1998. ISBN 1-85795-009-7.

- Manders, F. & Potts, R. Crossing the Tyne. Tyne Bridge Publishing. 2001. ISBN 1-85795-121-2.

- Anderson, D. Tyne Bridge, Newcastle in "Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers", March 1930 v. 230

- Prade, Marcel Les grands ponts du monde: Ponts remarquables d'Europe, Brissaud, Poitiers (France), ISBN 2902170653, 1990; pp. 274

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tyne Bridge. |

- Databases: Bridges On The Tyne, Engineering Timelines, and Tyne Bridge at Structurae

- Articles: BBC Inside Out - Tyne Bridge

- Map sources for Tyne Bridge.

- Images

- Historic photographs: Dorman Long collection, Pictures of Gateshead

- Aerial photographs: Britain from Above - aerial views of the bridge under construction and later in the 1930s, from the Aerofilms archive of English Heritage

- Photographs of Tyne Bridges: Peter Loud

- Video: BBC - Nation on Film

| Next crossing upstream | River Tyne | Next crossing downstream |

| Swing Bridge | Tyne Bridge Grid reference: NZ253637 |

Gateshead Millennium Bridge Footbridge |