Twelfth Night (holiday)

| Twelfth Night | |

|---|---|

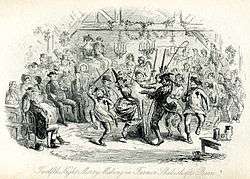

Mervyn Clitheroe's Twelfth Night party, by "Phiz" | |

| Observed by | Christians |

| Type | Christian |

| Significance | evening prior to Epiphany |

| Observances | Singing Christmas carols, chalking the door, merrymaking, having one's house blessed, attending church services |

| Date | 5 or 6 January |

| Frequency | annual |

| Related to |

Twelve Days of Christmas Christmastide Epiphany Epiphanytide |

Twelfth Night is a festival in some branches of Christianity marking the coming of the Epiphany. Different traditions mark the date of Twelfth Night on either 5 January or 6 January; the Church of England, Mother Church of the Anglican Communion, celebrates Twelfth Night on the 5th and "refers to the night before Epiphany, the day when the nativity story tells us that the wise men visited the infant Jesus".[1][2][3] In Western Church traditions, the Twelfth Night concludes the Twelve Days of Christmas; although, in others, the Twelfth Night may refer to the eve of the Twelfth Day.[4]

Bruce Forbes writes:

In 567 the Council of Tours proclaimed that the entire period between Christmas and Epiphany should be considered part of the celebration, creating what became known as the twelve days of Christmas, or what the English called Christmastide. On the last of the twelve days, called Twelfth Night, various cultures developed a wide range of additional special festivities. The variation extends even to the issue of how to count the days. If Christmas Day is the first of the twelve days, then Twelfth Night would be on January 5, the eve of Epiphany. If December 26, the day after Christmas, is the first day, then Twelfth Night falls on January 6, the evening of Epiphany itself.[5]

A belief has arisen in modern times, in some English-speaking countries, that it is unlucky to leave Christmas decorations hanging after Twelfth Night, a tradition originally attached to the festival of Candlemas (2 February), which celebrates the Presentation of Jesus at the Temple.[6] Other popular Twelfth Night customs include singing Christmas carols, chalking the door, having one's house blessed, merrymaking, as well as attending church services.[7][8]

Origins and history

In medieval and Tudor England, Candlemas traditionally marked the end of the Christmas season,[9] although later, Twelfth Night came to signal the end of Christmastide, with a new but related season of Epiphanytide running until Candlemas.[10] A popular Twelfth Night tradition was to have a bean and pea hidden inside a Twelfth-night cake; the "man who finds the bean in his slice of cake becomes King for the night while the lady who finds a pea in her slice of cake becomes Queen for the night."[11] Following this selection, Twelfth Night parties would continue and would include the singing of Christmas carols, as well as feasting.[11]

Traditions

Food and drink are the centre of the celebrations in modern times, and all of the most traditional ones go back many centuries. The punch called wassail is consumed especially on Twelfth Night, but throughout Christmas time, especially in the UK. Around the world, special pastries, such as the tortell and king cake, are baked on Twelfth Night, and eaten the following day for the Feast of the Epiphany celebrations. In English and French custom, the Twelfth-cake was baked to contain a bean and a pea, so that those who received the slices containing them should be designated king and queen of the night's festivities.[12]

In parts of Kent, there is a tradition that an edible decoration would be the last part of Christmas to be removed in the Twelfth Night and shared amongst the family.[13]

The Theatre Royal, Drury Lane in London has had a tradition since 1795 of providing a Twelfth Night cake. The will of Robert Baddeley made a bequest of £100 to provide cake and punch every year for the company in residence at the theatre on 6 January. The tradition still continues.[14]

In Ireland, it is still the tradition to place the statues of the Three Kings in the crib on Twelfth Night or, at the latest, the following Day, Little Christmas.

In colonial America, a Christmas wreath was always left up on the front door of each home, and when taken down at the end of the Twelve Days of Christmas, any edible portions would be consumed with the other foods of the feast. The same held true in the 19th–20th centuries with fruits adorning Christmas trees. Fresh fruits were hard to come by, and were therefore considered fine and proper gifts and decorations for the tree, wreaths, and home. Again, the tree would be taken down on Twelfth Night, and such fruits, along with nuts and other local produce used, would then be consumed.

Modern American Carnival traditions shine most brightly in New Orleans, where friends gather for weekly king cake parties. Whoever gets the slice with the "king", usually in the form of a miniature baby doll (symbolic of the Christ Child, "Christ the King"), hosts next week's party.

In the eastern Alps, a tradition called Perchtenlaufen exists. Two to three hundred masked young men rush about the streets with whips and bells driving out evil spirits.[9] In Nuremberg, until 1616, children frightened spirits away by running through the streets and knocking loudly at doors.[9] In some countries, the Twelfth Night and Epiphany mark the start of the Carnival season, which lasts through Mardi Gras Day.

Suppression

Twelfth Night in the Netherlands became so secularized, rowdy and boisterous that public celebrations were banned from the church.[15]

Old Twelfth Night

In some places, particularly southwest England, Old Twelfth Night is still celebrated on 17 January.[16] This continues the custom on the date determined by the Julian calendar.[17]

In literature

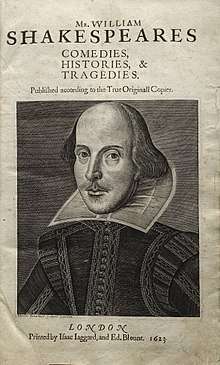

Shakespeare's play Twelfth Night, or What You Will was written to be performed as a Twelfth Night entertainment. The earliest known performance took place at Middle Temple Hall, one of the Inns of Court, on Candlemas night, 2 February 1602.[18] The play has many elements that are reversed, in the tradition of Twelfth Night, such as a woman Viola dressing as a man, and a servant Malvolio imagining that he can become a nobleman.

Ben Jonson's The Masque of Blackness was performed on 6 January 1605 at the Banqueting House in Whitehall. It was originally entitled The Twelvth Nights Revells. The accompanying Masque, The Masque of Beauty was performed in the same court the Sunday night after the Twelfth Night in 1608.[19]

Robert Herrick's poem Twelfe-Night, or King and Queene, published in 1648, describes the election of king and queen by bean and pea in a plum cake, and the homage done to them by the draining of wassail bowls of "lamb's-wool", a drink of sugar, nutmeg, ginger and ale.

Charles Dickens' 1843 A Christmas Carol briefly mentions Scrooge and the Ghost of Christmas Present visiting a children's Twelfth Night party.

In Chapter 6 of Harrison Ainsworth's 1858 novel Mervyn Clitheroe, the eponymous hero is elected King of festivities at the Twelfth Night celebrations held in Tom Shakeshaft's barn, by receiving the slice of plum cake containing the bean; his companion Cissy obtains the pea and becomes queen, and they are seated together in a high corner to view the proceedings. The distribution has been rigged to prevent another person gaining the role. The festivities include country dances, and the introduction of a "Fool Plough", a plough decked with ribands brought into the barn by a dozen mummers together with a grotesque "Old Bessie" (played by a man) and a Fool dressed in animal skins with a fool's hat. The mummers carry wooden swords and perform revelries. The scene in the novel is illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ("Phiz"). In the course of the evening, the fool's antics cause a fight to break out, but Mervyn restores order. Three bowls of gin punch are disposed of, and at eleven o'clock the young men make the necessary arrangements to see the young ladies safely home across the fields.

See also

References

- ↑ Beckford, Martin (6 January 2009). "Christmas ends in confusion over when Twelfth Night falls". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 26 May 2010.

- ↑ "Twelve days of Christmas". Full Homely Divinity. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

We prefer, like good Anglicans, to go with the logic of the liturgy and regard January 5th as the Twelfth Day of Christmas and the night that ends that day as Twelfth Night. That does make Twelfth Night the Eve of the Epiphany, which means that, liturgically, a new feast has already begun.

- ↑ Shorter Oxford English Dictionary. 1993.

...the evening of the fifth of January, preceding Twelfth Day, the eve of the Epiphany, formerly the last day of the Christmas festivities and observed as a time of merrymaking.

- ↑ Bratcher, Dennis (25 March 2013). "The Twelve Days of Christmas". Christian Resource Institute. Retrieved 28 December 2014.

The Twelfth Night is January 5th, the last day of the Christmas Season before Epiphany (January 6th). In some church traditions, January 5th is considered the eleventh Day of Christmas, while the evening of January 5th is still counted as the Twelfth Night, the beginning of the Twelfth day of Christmas the following day.

- ↑ Forbes, Bruce (2008). Christmas: A Candid History. University of California Press. p. 27. ISBN 9780520258020.

- ↑ "Of late years a belief has grown up that it is unlucky to leave [evergreens] hanging after Epiphany Eve (5 January), but this seems to be a modern notion [...] The older tradition was that they must come down by Candlemas, the day on which the wider ecclesiastical Christmas season ends." — Radford, ed. Cole (1961). Encyclopaedia of Superstitions. London: Hutchinson.

- ↑ Mangan, Louise; Wyse, Nancy; Farr, Lori (2001). Rediscovering the Seasons of the Christian Year. Wood Lake Publishing Inc. p. 69. ISBN 9781551454986.

Epiphany is often heralded by "Twelfth Night" celebrations (12 days after Christmas), on the evening before the Feast of Epiphany. Some Christian communities prepare Twelfth Night festivities with dram, singing, rituals - and food! ... Sometimes several congregations walk in lines from church to church, carrying candles to symbolize the light of Christ shining and spreading. Other faith communities move from house to house, blessing each home as they search for the Christ child.

- ↑ Pennick, Nigel (21 May 2015). Pagan Magic of the Northern Tradition: Customs, Rites, and Ceremonies. Inner Traditions – Bear & Company. p. 176. ISBN 9781620553909.

On Twelfth Night in Germanvspeaking countries, the Sternsinger (“star singers”) go around to houses carrying a paper or wooden star on a pole. They sing an Epiphany carol, then one of them writes in chalk over the door a formula consisting of the initials of the Three Wise Men in the Nativity story, caspar, Melchior, and balthasar, with corsses between them and the year date on either side; for example: 20 +M+B 15. This is said to protect the house and its inhabitants until the next Epiphany.

- 1 2 3 Miles, Clement A.. Christmas Customs and Traditions: Their History and Significance. Courier Dover Publications, 1976.

ISBN 0-486-23354-5. Robert Herrick (1591–1674) in his poem "Ceremony upon Candlemas Eve" writes:

- "Down with the rosemary, and so

- Down with the bays and mistletoe;

- Down with the holly, ivy, all,

- Wherewith ye dress'd the Christmas Hall"

- ↑ Davidson, Clifford (5 December 2016). Festivals and Plays in Late Medieval Britain. Taylor & Francis. p. 32. ISBN 9781351936613.

Playing seems to have continued after Twelfth Night, in the Epiphany season leading up to Candlemas on February 2, which sometimes was regarded as the last day of the Christmas season. We know that these weeks were an extension of the festive Christmas period.

- 1 2 Macclain, Alexia (4 January 2013). "Twelfth Night Traditions: A Cake, a Bean, and a King -". Smithsonian Libraries. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

And what happens at a Twelfth Night party? According to the 1923 Dennison’s Christmas Book, “there should be a King and a Queen, chosen by cutting a cake…” The Twelfth Night Cake has a bean and a pea baked into it. The man who finds the bean in his slice of cake becomes King for the night while the lady who finds a pea in her slice of cake becomes Queen for the night. The new King and Queen sit on a throne and “paper crowns, a scepter and, if possible, full regalia are given them.” The party continues with games such as charades as well as eating, dancing, and singing carols. For large Twelfth Night celebrations, a costume party is suggested.

- ↑ Miles & John, Hadfield (1961). The Twelve Days of Christmas. London: Cassell & Company. p. 166.

- ↑ Mark Esdale. "Main Page @ Bridge Farmers' Market".

- ↑ "The Baddeley Cake". Drury Lane Theatrical Fund. Retrieved 30 November 2013.

- ↑ Hoeven, Anke A. van Wagenberg-ter (1993). "The Celebration of Twelfth Night in Netherlandish Art". Simiolus: Netherlands Quarterly for the History of Art. 22 (1/2): 67. doi:10.2307/3780806. JSTOR 3780806.

- ↑ Iain Hollingshead, Whatever happened to ... wassailing?, The Guardian, 23 December 2005, retrieved 23 May 2014

- ↑ Xanthe Clay, Traditional cider: Here we come a-wassailing!, The Telegraph, 3 February 2011, retrieved 23 May 2014

- ↑ Shakespeare, William; Smith, Bruce R. (2001). Twelfth Night: Texts and Contexts. Boston: Bedford/St Martin's. p. 2. ISBN 0-312-20219-9.

- ↑ Herford, C. H. (1941). Percy & Evelyn Simpson, eds. Ben Jonson, Volume VII. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 169–201.

Further reading

- "Christmas". Catholic Encyclopedia. Retrieved 22 December 2005. Primarily subhead Popular Merrymaking under Liturgy and Custom.

- Christmas Trivia edited by Jennie Miller Helderman, Mary Caulkins. Gramercy, 2002

- Marix-Evans, Martin. The Twelve Days of Christmas. Peter Pauper Press, 2002

- Bowler, Gerry. The World Encyclopedia of Christmas. McClelland & Stewart, 2004

- Collins, Ace. Stories Behind the Great Traditions of Christmas. Zondervan, 2003

- Wells, Robin Headlam. Shakespeare's Humanism. Cambridge University Press, 2006

- Fosbrooke, Thomas Dudley c. 1810, 'Encyclopaedia of Antiquities' (Publisher unknown)

- J. Brand, 1813, 'Popular Antiquities', 2 Vols (London)

- W. Hone, 1830, 'The Every-Day Book' 3 Vols (London), cf Vol I pp 41–61.

Early English sources

(drawn from Hone's Every-Day Book, references as found):

- Vox Graculi, 4to, 1623: 6 January, Masking in the Strand, Cheapside, Holbourne, or Fleet-street (London), and eating of spice-bread.

- The Popish Kingdom, 'Naogeorgus': Baking of the twelfth-cake with a penny in it, the slices distributed to members of the household to give to the poor: whoever finds the penny is proclaimed king among them.

- Nichols, Queen Elizabeth's Progresses: An entertainment at Sudley, temp. Elizabeth I, including Melibaeus king of the bean, and Nisa, queen of the pea.

- Pinkerton, Ancient Scottish Poems: Letter from Sir Thomas Randolph to Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester dated 15 January 1563, mentioning that Lady Flemyng was Queen of the Beene on Twelfth-Day that year.

- Ben Jonson, Christmas, His Masque (1616, published 1641): A character 'Baby-cake' is attended by an usher carrying a great cake with a beane and a pease.

- Samuel Pepys, Diaries (1659/60): Epiphany Eve party, selecting of King and Queen by a cake (see King cake).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Twelfth Night. |

| Look up Twelfth Day or Twelfth Night in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Epiphany on Catholic Encyclopedia

- The Twelve Days of Christmas at The Christian Resource Institute

- William Shakespeare's "Twelfth Night"