Tullibody

Tullibody

| |

|---|---|

Residential area of Tullibody with the Ochils in the background | |

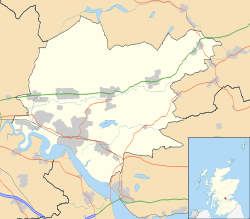

Tullibody Tullibody shown within Clackmannanshire | |

| Area | 3.03 sq mi (7.8 km2) |

| Population | 9,530 [1][2] (2012 est.) |

| • Density | 3,145/sq mi (1,214/km2) |

| OS grid reference | NS859951 |

| Council area | |

| Lieutenancy area | |

| Country | Scotland |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | ALLOA |

| Postcode district | FK10 |

| Dialling code | 01259 |

| Police | Scottish |

| Fire | Scottish |

| Ambulance | Scottish |

| EU Parliament | Scotland |

| UK Parliament | |

| Scottish Parliament | |

Tullibody (Scottish Gaelic: Tulach Bòide) is a town set in the Central Lowlands of Scotland. It lies north of the River Forth near to the foot of the Ochil Hills within the Forth Valley. The town is 1.8 miles (2.9 km) south-west of Alva, 1.8 miles (2.9 km) north-west[3] of Alloa and 4.0 miles (6.4 km) east-northeast of Stirling. The town is part of the Clackmannanshire council area.

According to a 2012 estimate the population of Tullibody is approximately 8,710[4] or 9,530 residents including the area of Cambus.[1]

History

There are remains of human activity in the Tullibody area from Mesolithic times. On Braehead Golf Course, the green-keepers found a midden containing shell remains of mussels, scallops and cockles dating back to 4000 BC. Known as The Braehead Shell Midden it is one of the few found on the north side of the Forth.[5] The Haer Stane, now part of Tullibody War Memorial, is said to have formed part of a circle of standing stones.[6][7]

It is thought that the church in Tullibody dates from the end of the fourth century[8] and St. Serf ministered to the church[9] in the 5th century on his journeys to Alva.[10][11] Folklore states that Kenneth MacAlpin, King of Scots, amassed his army on Baingle Brae before he fought and subdued the Picts. He is reported to have given Tullibody its name,[12] calling it "Tirly-bothy" meaning oath of the croft.[13] Certainly there was a standing stone on the main road to Stirling (near the Catholic Church) until the early 1900s when it is then reported to have been demolished to make ready for the road upgrading. An alternative toponymy has been suggested.[14]

David I of Scotland was responsible for Tullibody’s claim to fame when in 1149 he granted the lands and fishing rights to Cambuskenneth Abbey and it was then that the Auld Kirk was erected, where it still stands today.[15] Hugh de Roxburgh was the rector of Tullibody, Chancellor of Scotland and bishop of Glasgow in the late 12th century.[16] A 19th century map shows the church with the Priest's Well[17] and the Maiden Stone at the graveyard.[18]

Edward I of England, in his attempt to subdue the Scots in 1306 reportedly tried to build a castle in Tullibody, on the hill behind the Delph Pond. As it would have been of wooden construction, no one has ever found any proof.

In January 1560, William Kirkcaldy of Grange demolished part of Tullibody bridge to delay French troops returning to Stirling Castle. The French commander Henri Cleutin, known as General D'Oysel, took down the roof of the Auld Kirk to repair the bridge.[19] Tullibody, unlike Alloa, had its own Parish Church until the start of the 17th century when it lost its superior status and Alloa became a parish in its own right. Bishop Keith said of Alloa Parish that it "swallowed up the mother church" at Tullibody. The Abercrombys made The Auld Kirk their family cemetery.[20] In 1600 there were between four and five hundred communicant members, above the age of 16, at the church in Tullibody.[21]

In 1645, the Earl of Montrose, on the night before the Battle of Kilsyth, encamped his forces in the woods of Tullibody.[22] A daggered footnote in the Old Statistical Accounts suggests that Montrose was pursued by the Marquis of Lorn who probably camped at the spot[23] now known as Lorn's Hill.[24]

One of the earliest maps of the area was made by surveyor and cartographer John Adair in 1681.[25]

In 1745 Stirling's Secession preacher Ebenezer Erskine left Stirling which was under the control of the Jacobite army and preached to his people in the wood at Tullibody.[26]

Economy

Tullibody is a former mining town, although neither that industry nor any other major employers have a presence in the town, with many of the residents now commuting to Stirling and Alloa to work. Historically, there was work with wool employing 30-40 people[27] and a tannery[28] on Alloa Road, which employed 30 to 40 men processing leather and making glue.[29] The site near the Delph Pond,[30] a former curling pond,[31] was demolished, being replaced with new housing in 2017.[32] Since the late 1990s and early 2000s, there has been a rapid expansion in housebuilding in the town, with 400 new houses built on the north side of the village in the last 5 years.

Education

The town has four primary schools – St. Bernadette's, Abercromby, Banchory and St. Serf's – with young people also attending the local high schools including Lornshill Academy, St Modan's High School, Alloa Academy and Alva Academy.

Notable people

- Servicemen from Tullibody and Cambus include 27 men from WW1 and 16 from WW2 whose names are recorded on the Tullibody War Memorial.[33][34]

- Lieutenant-General Sir Ralph Abercromby, KCB (sometimes spelled Abercrombie) (7 October 1734 – 28 March 1801) was a British lieutenant-general noted for his services during the Napoleonic Wars.

- William Burns Paterson founder of Tullibody Academy[35] and Alabama State University.

- Robert Dick (January 1811 – 24 December 1866), geologist and botanist was born in Tullibody.

- Civil engineer Ralph Walker (1749 –– 1824) was born in Tullibody.

In the arts

Tullibody Old Kirk is depicted in George Harvey’s famous work of 1848 Quitting the Manse.[36] The work is rarely on display due to bad bitumen damage caused by Harvey’s experiments with varnish.[37] The subject of the painting is a minister and his wife leaving their home in a national event known as The Disruption where around a third of the ministers quit the Church of Scotland protesting that congregations must be able to choose their own minister. This was often done at considerable personal sacrifice as they left their salaries, their homes and sometimes their congregations to set up the Free Church in May 1843.[38] There was a Free Church in Tullibody[39] in the 19th century.[40] Harvey is known to have done many studies for his paintings and Tullibody Church is owned by the Stirling Smith Art Gallery and Museum.[41]

There are at three poems relating to The Maiden's Stone.[42] One is a three-part poem called "The Maid of Myreton; A Tale of Tullibody".[43] The subject of the poem is a parish priest Peter Beaton who fell in love with Martha, the only child of Wishart, the laird of Myreton.[44] The affair did not end well with her dying of a broken heart but leaving a letter for her father:

The letter opened, and thereon was wrote

What sort of tomb she wished, the place and spot.

"Place me," it ran, "in coffin made of stone.

Nor tree plant near, nor earth be laid thereon,

And let the distance be about a perch

Before the middle entrance of the church,

So that false Beaton, passing out and in.

May see the relic of his pride and sin."

He saw it not, already he had fled;

Another priest read service o'er the dead;

And those who sought him, sought him all in vain.

He ne'er was seen by living man again.

Long, long the church was wrapt in silent gloom,

The door built up that faced the Maiden's Tomb;

The tomb lies open, empty, broken, marred,

In ancient Tullibody's quiet graveyard.

There is also a longer poem about the same subject called "The Maiden's Stone of Tullibody".[45] A third, much shorter, poem called Martha of Myreton comes sandwiched between a poem about the same graveyard and another entitled Tullibody which repeatedly describes Tullibody as sweet.[46]

Tullibody, as well as having a famous stone coffin, is also recorded to have had an iron coffin case as an attempt to thwart local body-snatchers.[47] These deterrents were known as mortsafes.

Punch magazine ran a poem about an eagle, which threatened a baby in its pram, which could not be diverted even when offered three different kinds of biscuit.[48]

A song is recorded in the same volume, called "Gently rising Tullibody" which praises the town and Abercromby’s military victory in Egypt over the French. Yet another poem which mentions Tullibody is from the same book and involves a dialogue between a Besom Cadger and a Fisherwoman. The title is Causey Courtship.[49]

See also

.jpg)

References

- 1 2 Population of settlements, ClacksWeb Retrieved 2017-07-06.

- ↑ Includes the area of Cambus

- ↑ Beveridge, David (1888). Between the Ochils and Forth: A Description, Topographical and Historical of the Country between Stirling Bridge and Aberdour. Edinburgh and London: W. Blackwood. pp. 211–217. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- ↑ "Estimated population of localities by broad age groups, mid-2012" (PDF). Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- ↑ "Alloa, Braehead". Canmore. Historic Environment Scotland. Retrieved 6 July 2017.

- ↑ "Tullibody, Haer Stane". Canmore. Historic Environment Scotland. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- ↑ Bennett, Paul. "Tullibody Stone Circle, Clackmannanshire". The Northern Antiquarian. Retrieved 7 July 2017.

- ↑ Jamieson, John (1902). Bell the Cat: Or, who Destroyed the Scottish Abbeys?. Stirling: Eneas Mackay. pp. 245–247. Retrieved 5 July 2017.

- ↑ Sinclair, John; Frame, James; Erskine, John Francis (1791). The statistical account of Scotland. Drawn up from the communications of the ministers of the different parishes. Edinburgh: W. Creech. p. 642. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

- ↑ Mackay, Aeneas James George (1896). A history of Fife and Kinross. Edinburgh: Blackwood. p. 12. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ↑ Fittis, Robert Scott (1878). Sketches of the olden times in Perthshire. Perth: Printed at the Constitutional Office. p. 476. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ↑ "Tullibody". Angel Fire. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- ↑ Barbieri, M. (1857). A Descriptive and Historical Gazetteer of the Counties of Fife, Kinross and Clackmannan. Edinburgh: Maclachlan & Stewart. pp. 76–77. Retrieved 4 July 2017.

- ↑ Fergusson, Robert Menzies (1905). Logie: A Parish History. Paisley: A. Gardner. p. 290. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

- ↑ "Oblique aerial view centred on the churches, burial-ground and church hall, taken from the SE". Canmore. Historic Environment Scotland. Retrieved 7 July 2017.

- ↑ McClintock, John; Strong, James (1887). Cyclopaedia of Biblical, Theological, and Ecclesiastical Literature (volume II (CO-Z) ed.). New York: Harper. p. 807. Retrieved 22 July 2017.

- ↑ Bennett, Paul. "Priest's Well, Tullibody, Clackmannanshire". The Northern Antiquarian. Retrieved 7 July 2017.

- ↑ "OS Six inch 1st edition 1843-1882". National Library of Scotland. Ordnance Survey. Retrieved 7 July 2017.

- ↑ Knox, John; Lain, David (1846). The works of John Knox. Volume 2, Book 3. Edinburgh: Bannatyne Club. p. 14. Retrieved 5 July 2017.

- ↑ Brotherston, Peter (1845). The new statistical account of Scotland (volume 8 ed.). Edinburgh and London: W. Blackwood and Sons. p. 57. Retrieved 7 July 2017.

- ↑ Lorimer, John Gordon (1842). Historical sketch of the Protestant Church of France : from its origin to the present time, with parallel notices of the Church of Scotland during the same period. Philadelphia: Presbyterian Board of Publication. p. 103. Retrieved 7 July 2017.

- ↑ Lewis, Samuel (1851). A topographical dictionary of Scotland, comprising the several counties, islands, cities, burgh and market towns, parishes, and principal villages, with historical and statistical descriptions: embellished with engravings of the seals and arms of the different burghs and universities. London: S. Lewis and co. pp. 38–40. Retrieved 6 July 2017.

- ↑ "OS 25 inch, 1892-1905 with Bing overlay". National Library of Scotland. Ordnance Survey. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- ↑ Sinclair, John; Frame, James; Erskine, John Francis (1791). The statistical account of Scotland. Drawn up from the communications of the ministers of the different parishes. Edinburgh: W. Creech. p. 601. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

- ↑ Adair, John. "A map of Strath Devon and the district between the Ochils and the Forth". National Library of Scotland. Retrieved 6 July 2017.

- ↑ Alloa and its environs. A descriptive and historical guide. Alloa: James Lothian. 1861. p. 31. Retrieved 4 November 2017.

- ↑ Sinclair, John; Frame, James; Erskine, John Francis (1791). The statistical account of Scotland. Drawn up from the communications of the ministers of the different parishes. Edinburgh: W. Creech. pp. 622–623. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

- ↑ "Tullibody Tannery - 1806 to Now". Tullibody. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- ↑ Brodie, William (1845). The new statistical account of Scotland (Vol 8 ed.). Edinburgh and London: W. Blackwood and Sons. pp. 1–65. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- ↑ Connor, Mark (13 September 2017). "Woman creates model of 1920's Tullibody". alloa and hillfoots advertiser. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ↑ "OS 25 inch, 1892-1905". National Library of Scotland. Ordnance Survey. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- ↑ "Development Brief For Land At Alloa Road, Tullibody" (PDF). Clacksweb. Clackmannanshire Council. Retrieved 4 July 2017.

- ↑ "New plaque unveiled at Haer Stane war memorial ceremony in Tullibody". Alloa Advertiser. 8 November 2013. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- ↑ Burns, Ashleigh (25 July 2018). "New tributes to war dead unveiled in Tullibody". Alloa Advertiser. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- ↑ Burns, Ashleigh (17 April 2016). "William Burns Paterson, born in Tullibody in 1849, helped to champion education in Alabama". Alloa & Hillfoots Advertiser. Retrieved 5 July 2017.

- ↑ "Reformation". Tullibody. Angel Fire. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- ↑ Harvey, George. "Quitting the Manse". National Galleries of Scotland. Antonia Reeve. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- ↑ Brown, Thomas (1893). Annals of the disruption. Edinburgh: Macniven & Wallace. pp. 132–143. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- ↑ The "Stirling Sentinel" portrait gallery. Stirling: Cook & Wylie. 1897. pp. 157–159. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- ↑ "The Free Church in Tullibody". Tullibody. Angel Fire. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- ↑ Harvey, George. "Tullibody Church". ArtUK. The Stirling Smith Art Gallery & Museum. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- ↑ "Myretoun Maid". Tullibody. Angel Fire. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- ↑ Towers, Walter (1885). Poems, Songs, and Ballads. Glasgow: A. Bryson & Co. pp. 10–39. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- ↑ Rogers, Charles (1872). Monuments and monumental inscriptions in Scotland. volume 2. London: for the Grampian Club [by] C. Griffin. p. 61. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- ↑ Beveridge, Andrew (1871). The Maiden's Stone Of Tullbody And Other Poems. Glasgow: Thomas Murray & Sons. pp. 13–61. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- ↑ Beveridge, James (1885). The Poets of Clackmannanshire: With Numerous Specimens of Their Writings. Glasgow: J.S. Wilson. pp. 34–37. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- ↑ Hallen, A. W. Cornelius (1889). Northern notes and queries or the Scottish antiquary. volume 3. Edinburgh: David Douglas. p. 20. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- ↑ Punch Vol-clxxi. London: The Office. 1926. p. 332. Retrieved 24 July 2017.

- ↑ Beveridge, James (1885). The Poets of Clackmannanshire: With Numerous Specimens of Their Writings. Glasgow: J.S. Wilson. pp. 40–44. Retrieved 8 July 2017.