Trams in Jakarta

| Trams in Jakarta | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||

| Operation | |||||||||||||

| Locale | Jakarta, Indonesia | ||||||||||||

| Status | Closed | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

The Jakarta tram system was a transport system in Jakarta, Indonesia. Its first-generation tram network first operated as a horse tram system, and was eventually converted to electric trams in the early twentieth century. Jakarta tramway served the city for almost a century until its closing in 1962.

History

Horse-drawn trams

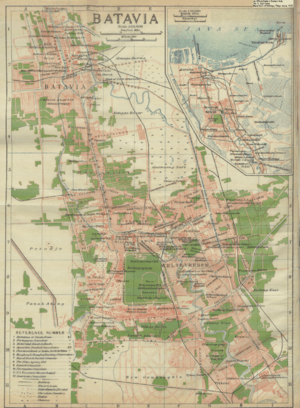

Jakarta tramlines started its life on April 20, 1869[1][2] as Bataviasche Tramweg-Maatschappij or BTM (Dutch "Batavia Tramway Company"). The first line of Jakarta tramway ran north-south from Old Batavia (close to the Amsterdam Gate), through the Molenvliet West, and ended at Harmonie. Later in the same year, the second line was opened. The second line operated from Harmonie - Tanah Abang and back to Harmonie - Noordwijk - Kramat - Meester Cornelis. The BTM operated horse trams on a track gauge of 1188mm. At its opening, the tram system was used by 1500 passengers.[3] In September of the same opening year, 7000 passengers used the tram system.[3]

Batavia's many social classes and races used the same passenger space in the tram. BTM horse-drawn trams were relatively unpopular for the Europeans.[4] The high tax for horses and the financing issues in the BTM led to the system being taken over by the Dummler & Co.In year 1880 BTM tram was taken over by Dummler & Co.[5]

The horses for the trams were brought from all over the archipelago, e.g. from Sumba, Timor, Sumbawa, Tapanuli, Priangan and Makassar.[4]

Steam trams

In 1882, Dummler & Co. was taken over by the Nederlands-Indische Tramweg Maatschappij or NITM. NITM had been formed in 1881. NITM ordered fireless steam locomotives from the Hohenzollern Locomotive Works to replace the horse-drawn trams in 1883. The steam locomotives proved to be a success and so service was expanded. At this period, NITM tram operated everyday from 5.45 AM to 6.30 PM.[4] Tram arrived every 7 to 10 minutes.[4] More was supplied until the year 1907, at that time 34 locomotives had been delivered to Batavia. On March 6, 1906, the Hohenzollern NITM Fireless Tram No 4 was destroyed when a boiler exploded while the being recharged. The explosion also damaged an adjacent locomotive and part of the tram shed at Kramat.[5]

In 1887, three classes of trams were introduced to the racially stratified society of Batavia. The classes corresponded to the different races of Batavia: the Europeans, the Chinese, and the natives.[6] The first and second classes carriage were each known as Trailer type A and Trailer type B. These trailers were built by Beynes in 1882.

The 1920s was the golden age of trams in Jakarta. In year 1920, the former two companies carried more than 21 million passengers. In year 1921, a new batch of 17 locomotives was supplied by Hohenzollern. These new locomotives were built for 1067mm gauge, the same gauge as the Staatsspoorwegen railway system.[5]

In the 1930s, the number of tram users declined from 21 million in the 1920s to 11 million. The trend would continue to worsen to 6 million in 1936. Fare reduction in 1936 caused a slight increase of tram users.[7]

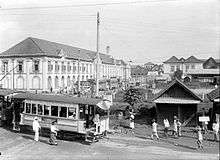

Electric trams

Plan for electric trams in Batavia had started since 1886.[4] On 10 April 1899, the electric trams officially opened, operated by Batavia Elektrische Tram Maatschappij (BETM).[8] This electric tram system was even earlier than the first electric tramway in the Netherlands the Haarlem-Zandvoort line, which was opened in July 1899.[8] The first electric tramway served the route Harmoni - Pasar Tanah Abang - Dierentuin (Cikini). In November 1899, the electric tramway was extended toward Tanah Abang railway station, but was closed 5 years later. In 1900, the electric tramway was extended toward Jembatan Merah, Tanah Tinggi and Gunung Sahari.[8] To reach Kampung Lima (now Jalan Wahid Hasyim), the tramway had to cross Ciliwung at what is now the bridge connecting Jalan Kramat IV and Jalan A.A. Kali Pasir.[8]

Batavia had both steam and electric trams from 1899 to 1933. On July 31, 1930, the steam tram lines NITM were merged with the Batavia Electric Tramway BETM and adopted the name Bataviasche Verkeers Maatschappij N.V. or BVM.[9] The BVM owns and operates the entire tramway system of Batavia. The BVM trams ran through six lines. On March 1, 1934, the rebuilding of the electrification of the tram lines and the adaptation to the techniques of the electric streetcars were taken into effect.[10] This program completely eliminate the steam from Batavia, which had stopped operating since 1933.[5]

At this time, the trams are still divided into classes based on race. The first class carriage is for the Europeans. The much humbler second and third class carriages were for the Chinese and the Natives. The pikulan carriage (pikolanwagen) is used for transporting goods e.g. fish and vegetables, typical of Batavia. Of the passenger traffic, about 15 percent came from the first class carriage and 85 percent from the second and third class carriage. In 1937, the BVM owned 42 large motor cars, 39 small motor cars, 23 flat trucks, and 52 trailers.[6]

Post-independence and decline

The Japanese troops managed to occupy Batavia and the entire Dutch Indies in March 1942. At the same time, the BVM was confiscated and was made the Tentara Nippon Batavia Tram. In June 1942, it became Seibu Rikuyo Batavia Shiden, and later Jakarta Shiden.[11] In 1945, the Japanese abolished the racially stratified classes as a political gesture just before the end of the World War. All the former Dutch workers were send to internment camps. Dutch names were replaced with Japanese-Malay names. Japanese symbols were also installed into the trams, e.g. the sakura symbol.[11]

The BVM was returned to the BVM in October 1947. The second class was also reintroduced by the Dutch who still believe that the colonial era still existed. Following the secure of independence in the Indonesian National Revolution, the two distinct carriages for different classes still exist, but used independently by native Indonesians.

Following the independence of Indonesia, Jakarta trams were still operated by the private company BVM. In the early 1950s, Jakarta tramways stretched across Jakarta from Pasar Ikan in the north to Jatinegara in the south. Trams (or Trem in Indonesian) were very popular because of its low cost. Many native passengers felt that as an independent nation, they are no longer required to pay fares, so many decided to skip paying their fares. Trams are always overflow with people so the conductors could not check the passengers on board. Many people decided to hold onto the tram instead of getting in. Very often people go in and out through the windows instead.[12] There was also a rise in labor unrest as increasingly confident workers sought better conditions. Greater competition from buses was also an issue. All of these caused huge impact on BVM's finances.[13]

On July 1, 1954, The BVM tramway company was officially taken over by the Indonesian government and renamed the Perusahaan Pengangkutan Djakarta or PPD.[14] Under the management of PPD, the trams was repainted with patriotic red and white. Financial issues remained partly because of the increasing popularity of buses and automobiles (opelet). President Sukarno was instrumental in the abolition of the tram and there were rumors that President Sukarno did not believe trams had a place in the modern Jakarta he was planning.[15] By April 1960, trams operated only from Senen and Kramat to Jatinegara. By 1962, after almost one century, the trams ceased to operate and disappear forever from Jakarta.[6]

Following the shut down of the tramlines infrastructure, public transportation trend in Jakarta became more informal than formal. When the tram was shut down, the opelet easily took over their customers. The state-owned PPD was allocated a very inadequate fleet of buses. In the 1960s the opelet were supplemented on new routes by bemo, which is actually smaller three-wheeled Daihatsu Midget vans with a two-stroke engine and room in the cabin behind for only six passengers.[15]

Routes

At its most extensive, the total length of tram line system in Jakarta was 40 km divided into six different lines. The 14 km main line number 1 is the oldest and the most important. In line number 1, an excellent daily service of every six minutes in the peak hour (7.5 minutes off-peak) was maintained. The service of the other lines was of excellent 7.5 (10) minutes.[16]

Rolling stock

The list provide only steam-tram rolling stock of Batavia until the year 1924.[5] The list is sorted by its year.

| Type | Manufacturer | Year | Quantity | NITM number | Seats capacity | Standing capacity | Picture | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trailer | Bonnefond | 1869 | unknown | unknown | 40[3] | unknown |  |

Horse-drawn (3-4 horses),[3] 1188mm gauge |

| Fireless locomotive | Hohenzollern | 1882-1883 | 21 | 1-21 | not applicable | not applicable | 1188mm gauge | |

| Fireless locomotive | Hohenzollern | 1884-1907 | 13 | 22-34 | not applicable | not applicable | 1188mm gauge | |

| Steam locomotive | Hohenzollern | 1921 | 17 | 51-67 | not applicable | not applicable | 1067mm gauge | |

| Trailer type A | Beynes | 1882 | 14 | 1-14 | 16 | 16 | Became BVM A1-A14 | |

| Trailer type B | Beynes | 1882 | 14 | 51-64 | 26 | 16 | 52 & 55 became type A 80 & 81 in 1925. 23 survivors became BVM B101-B123 | |

| Trailer type A | Beynes | 1882-1889 | 9 | 91-99 | 24 | 16 | ||

| Trailer type B | Beynes | 1882-1889 | 7 | 101-107 | 34 | 16 | Became BVM AB201-AB207 | |

| Trailer type B | Beynes | 1883 | 2 | 151, 152 | 40 | 16 | Became BVM AB208, AB209 | |

| Trailer type AB | Beynes | 1884 | 2 | 202, 202 | 40 | 16 | ||

| Trailer type c\C | Beynes | 1887-1897 | 14 | 251-264 | 40 | 28 | Became BVM AB208, AB209 | |

| Trailer type AB | Beynes | 1897 | 2 | 211, 212 | 40 | 16 | ||

| Trailer type AB | NITM | 1904 | 6 | 221-226 | 40 | 20 | Became BVM AB253, AB254, AB256, C505, C506, C508 | |

| Pikolanwagen | Werkspoor | 1904-1924 | 28 | 1-28 | not applicable | not applicable | 23 survivors became P1-P23 | |

| Trailer type C | NITM | 1908-1810 | 7 | 271-277 | 40 | 28 | 274, 275 & 277 became type AB 231-233 in 1928. Later became 501, 507 & 508. | |

| Trailer type AB | Werkspoor | 1922-1923 | 21 | 301-321 | 36 | 28 | Became BVM AB301-AB318, C422-C424 | |

| Trailer type C | Werkspoor | 1922-1923 | 21 | 401-421 | 42 | 53 | Became BVM C401-C421 |

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Trams in Jakarta. |

References

- ↑ Teeuwen 2010, p. 1.

- ↑ Merrillees 2015, p. 58.

- 1 2 3 4 Sulaeman 2017, p. 7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Sulaeman 2017, p. 8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Nederlands-Indische Tramweg Maatschappij". Searail Malayan Railways. Archived from the original on April 2, 2017. Retrieved April 2, 2017.

- 1 2 3 Merrillees 2015, p. 61.

- ↑ Teeuwen 2010, p. 4.

- 1 2 3 4 Sulaeman 2017, p. 9.

- ↑ http://www.oudefondsen.nl/overige/bataviasche-verkeers-maatschappij-31-juli-1930-amortisatiebewijs-f-100000/

- ↑ Teeuwen 2010, p. 2.

- 1 2 Sulaeman 2017, p. 18.

- ↑ Merrillees 2015, p. 59.

- ↑ Merrillees 2015, p. 60.

- ↑ UNDANG-UNDANG DARURAT REPUBLIK INDONESIA NOMOR 10 TAHUN 1954

- 1 2 Dick & Rimmer 2003, p. 282.

- ↑ Dick & Rimmer 2003, p. 279.

Cited works

- Dick, Howard; Rimmer, Peter J. (2003). Cities, Transport and Communications - The Integration of Southeast Asia since 1850. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9781349390229.

- Duparc, H.J.A. (1972). Trams en Tramlijnen: De Elektrische Stadstrams op Java. Rotterdam: Wyt. ISBN 9789060075821.

- Merrillees, Scott (2015). Jakarta: Portraits of a Capital 1950-1980. Jakarta: Equinox Publishing. ISBN 9786028397308.

- Sulaeman, Adriansyah Yasin (2017). Trem Batavia, Mutiara Transportasi Jakarta Yang Terlupakan [Batavian Tram, The Forgotten Pearl of Jakarta's Transportation]. Breda: Issuu.

- Teeuwen, Dirk (2010). "From horsepower to electrification - Tramways in Batavia-Jakarta 1869-1962" (PDF). Rendez-vous Batavia. Indonesia-Dutch Colonial Heritage. Retrieved April 22, 2017.