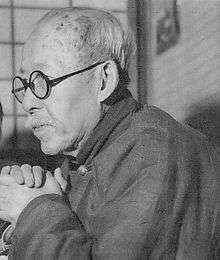

Torii Ryūzō

| Ryuzo Torii | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

March 4, 1870 |

| Died | January 14, 1953 (aged 82) |

| Other names | 鳥居龍藏 |

| Occupation | anthropologist, ethnologist, archaeologist and folklorist |

Ryuzo Torii (鳥居 龍藏; May 4, 1870 – January 14, 1953) was a Japanese anthropologist, ethnologist, archaeologist and folklorist. He was known for his anthropological research in China, Taiwan, Korea, Russia, Europe, etc. His research took him all over East Asia and South America.

Torii first made use of a camera while conducting field-work in Northeastern China in 1895. In 1900, Torii was assisted in his research by interpreter Ushinosuke Mori. Described as "a pioneer in the use of the camera in anthropological field-work",[1] Torii inspired other researchers, including Mori, to make use of photographs.

Early life

Torii was born on the island of Shikoku, in the Tokushima quarter of Higashi Senba-chō (東船場町), into a merchant family. From an early age, he was a passionate collector of artifacts of all kinds, though he generally showed little interest in schoolwork. For a time he abandoned school, until the guidance of an understanding teacher (Tominaga Ikutarō:富永幾太郎)[2] convinced him to complete his schooling. One of his hobbies was local history, and he pursued research on his home region.[3]

In his teens, he had already begun writing articles on anthropological topics. These came to the attention and appreciation of Tokyo Imperial University (TIU) professor of anthropology Tsuboi Shōgorō (坪井正五郎). Shōgorō took an interest in the young Torii, and hurried to Tokushima, to advise Torii to study anthropology. Acting on Shōgorō's advice, Torii moved to Tokyo at age 20.[4]

Career

He made an early reputation with his work on the native Ainu people of the Kuril Islands.[5]

Torii used eight different languages in his studies, and could use Ainu language. His article "Ainu people in Chishima Island", written in French, is a landmark in Ainu studies.

Torii spent almost all of his life in anthropology field-work (research). He insisted that: "Studies should not be done only in the study room. Anthropology is in the fields and mountains." He insisted that anthropological theories should be backed by strong empirical evidence.[6]

Torii began to use sound recording in anthropology research in domestic research at Okinawa Prefecture.

Torii is famous for research performed outside of Japan, but he started in Japan, from his hometown to almost everywhere in that country from Hokkaido to Okinawa. During his time at TIU, he studied Japan, on the invitation of various prefectures, villages, streets, etc. After completing his research in an area, he always held an exhibition, lecturing and showing discoveries. The Torii style is research, exhibit and lecture.[7] In 1898 he became an assistant at TIU.

In 1895, TIU sent Torii to Northeast China at Riao-dong Peninsula, his first overseas posting. In 1896, the University sent Torii to Taiwan. [8] He was posted in 1896 to Taiwan.

In 1899 he worked in Hokkaido and Chishima Island, to study the Ainu people, yielding a 1903 book Chishima Ainu, on the Kuril Ainu.

In 1900 he completed the first ascent of Taiwan's "Yu-mountain" (at the time, "Shin Taka-mountain").

In 1905 he became a TIU lecturer.

In 1906 he was engaged by the Karachin Royal Family of Mongolia. Kimiko worked as a teacher at Karachin Girl-School. Torii became a professor of Karachin Boy-School.

In 1911 Torii conducted field-work in Korea. At the time Sada Sekino described an ancient tomb as a Goguryeo artifact. Torii pointed out that it instead belonged to Han dynasty. This cost him friends, since Sekino was a powerful figure at TIU. Torii proved that the Han Chinese had arrived in Korea at an early period.[9]

In 1921 Torii earned a PhD in anthropology from TIU.

In 1922 Torii became an Assistant Professor at TIU.

In1924 Torii left TIU and established Ryuzo Torii Institute, staffed by his family members.

In 1928 Torii worked on establishing Sophia University in Tokyo. It was the only foreign school there for many years. As a Catholic anthropologist, Torii worked hard: he did all procedures for Ryuzo Torii and succeeded in lifting it up to a university level. It is a great achievement of Torii in internationalizing Japanese universities.[10]

In 1939 he joined the Harvard–Yenching Institute, the top Institute for Asian studies in the US at the time as an "Invited Professor". A sister university of Harvard was named Yenching University in Peking, China, and was an American missionary school. The Japanese Army could not come into this University until the Pearl Harbor attack. Torii was sent to this American area in China by the Institute, where his China anthropology studies reside, during the Second Sino-Japanese War.[11]

In 1951 Torii returned to Tokyo, Japan.

Recognition

In 1920 Torii was honored for an Ordre des Palmes Academiquesiques of France. The award disappeared within the university.

In 1964 the "Torii' Memorial Museum" was established by Tokushima prefecture, at Naruto area. It is in a Japanese traditional castle on the top of Myoken Mountain. Funds came from local people, showing their memory and love for Ryuzo Torii. In 2010 the Museum moved to Tokushima city in the "Forest of Culture" area.

Personal life

In 1901 he married Kimiko, daughter of a famous samurai in Tokushima. She was talented in music, language and education.

In the wake of Yoshino Sakuzō's criticism of Japan's Imperial ambitions in Korea, Torii aligned himself with those who justified Japanese annexation on the grounds that the contemporary consensus worldwide in linguistics, anthropology and archaeology was that the Korean and Japanese people were one and the same 'race/people' (dōminzoku).[12][lower-alpha 1]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Japanese original, Tan'itsu minzoku shinwa no kigen, Shin'yōsha, Tokyo 1995 pp.153ff.

Citations

- ↑ Bennett, Terry (1997). Korea: Caught in Time. Garnet Pub Limited. p. 16. ISBN 1859641091.

- ↑ Torii Ryūzō Zenshū, Asahi Shinbunsha, Tokyo, Vol.12 1977 p.24.

- ↑ Torii Ryūzō Zenshū, Asahi Shinbunsha, Tokyo 1975 vol.1 pp.1-12.

- ↑ "Memo of an Old Student" (Torii Ryūzō, ある老学徒の手記

- ↑ Siddle 1997, p. 142.

- ↑ 『Life of Ryuzo Torii』by Torii Ryuzo Memorial Museum

- ↑ "Achievements of Ryuzo Torii" by Tadashi Saito

- ↑ "Life of Ryuzo Torii", "Exhibitin" by Torii's Memorial Museum

- ↑ "Ryuzo Torii' s achievement" by Tadashi Saito

- ↑ "Studies on Ryuzo Torii No. 1"

- ↑ "Life of Ryuzo Torii" by Torii's Memorial Museum

- ↑ Oguma 2002, pp. 126-127.

Sources

- Oguma, Eiji (2002). A Genealogy of Japanese Self-images. Trans Pacific Press. ISBN 978-1-876-84304-5.

- Siddle, Richard (1997). "The Ainu and the Discourse of 'Race'". In Dikötter, Frank. The Construction of Racial Identities in China and Japan: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives. C. Hurst & Co. ISBN 978-1-850-65287-8.