Throne of Blood

| Throne of Blood 蜘蛛巣城 | |

|---|---|

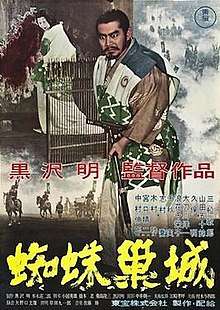

Original Japanese poster | |

| Directed by | Akira Kurosawa |

| Produced by |

|

| Screenplay by |

|

| Based on |

Macbeth by William Shakespeare (uncredited) |

| Starring | |

| Music by | Masaru Sato |

| Cinematography | Asakazu Nakai |

| Edited by | Akira Kurosawa |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Toho |

Release date |

|

Running time | 110 minutes |

| Country | Japan |

| Language | Japanese |

Throne of Blood (蜘蛛巣城 Kumonosu-jō, "Spider Web Castle") is a 1957 Japanese samurai film co-written and directed by Akira Kurosawa. The film transposes the plot of William Shakespeare's play Macbeth from Medieval Scotland to feudal Japan, with stylistic elements drawn from Noh drama. The film stars Toshiro Mifune and Isuzu Yamada in the lead roles, modelled on the characters Macbeth and Lady Macbeth.

As with the play, the film tells the story of a warrior who assassinates his sovereign at the urging of his ambitious wife. Kurosawa was a fan of the play and intended to make his own adaptation for several years, delaying it after learning of Orson Welles' Macbeth (1948). Among his changes was the ending, which required archers to fire arrows around Mifune. The film was shot around Mount Fuji and Izu Peninsula.

Despite the change in setting and language and numerous creative liberties, Throne of Blood often is considered one of the better film adaptations of the play. It won two Mainichi Film Awards, including Best Actor for Mifune. A stage adaptation by Ping Chong followed in 2010.

Plot

Generals Miki and Washizu are Samurai commanders under a local lord, Lord Tsuzuki, who reigns in the castle of the Spider's Web Forest. After defeating the lord's enemies in battle, they return to Tsuzuki's castle. On their way through the thick forest surrounding the castle, they meet a spirit, who foretells their future. The spirit tells them that today Washizu will be named Lord of the Northern Garrison and Miki will now be commander of the first fortress. She then foretells that Washizu will eventually become Lord of Spider's Web Castle, and finally she tells Miki that his son will also become lord of the castle. When the two return to Tsuzuki's estate, he rewards them with exactly what the spirit had predicted. As Washizu discusses this with Asaji, his wife, she manipulates him into making the second part of the prophecy come true by killing Tsuzuki when he visits.

Washizu kills Tsuzuki with the help of his wife, who gives drugged sake to the lord's guards, causing them to fall asleep. When Washizu returns in shock at his deed, Asaji grabs the bloody spear and puts it in the hands of one of the three unconscious guards. She then yells "murder" through the courtyard, and Washizu slays the guard before he has a chance to plead his innocence. Tsuzuki's vengeful son Kunimaru and an advisor to Tsuzuki, Noriyasu, both suspect Washizu as the traitor and try to warn Miki, who refuses to believe what they are saying about his friend. Washizu is unsure of Miki's loyalty, but chooses Miki's son as his heir, since he and Asaji have been unable to bear a child of their own. Washizu plans to tell Miki and his son about his decision at a grand banquet, but Asaji tells him that she is pregnant, which leaves him with a quandary concerning his heir, as now Miki and his son have to be eliminated.

During the banquet Washizu drinks sake copiously because he is clearly agitated, and at the sudden appearance of Miki's ghost, begins losing control. In his delusional panic, he reveals his betrayal to all by exclaiming that he is willing to slay Miki for a second time, going so far as unsheathing his sword and striking over Miki's mat. Asaji, attempting to pick up the pieces of Washizu's blunder, tells the guests that he is drunk and that they must retire for the evening. Then one of his men arrives with the severed head of Miki. The guard also tells them that Miki's son escaped.

Later, distraught upon hearing of his child is stillborn and in dire need of help with the impending battle with his foes, he returns to the forest to summon the spirit. She tells him that he will not be defeated unless the very trees of Spider's Web forest rise against the castle. Washizu believes this is impossible and is confident of his victory. Washizu knows he must kill all his enemies, so he tells his troops of the last prophecy, and they share his confidence. The next morning, Washizu is awakened by the screams of attendants. Striding into his wife's quarters, he finds Asaji in a semi-catatonic state, trying to wash clean the imaginary foul stench of blood from her hands, obviously distraught at her grave misdeeds. Distracted by the sound of his troops moving outside the room, he investigates and is told by a panicked soldier that the trees of Spider's Web forest "have risen to attack us". The prophecy has come true and Washizu is doomed.

As Washizu tries to get his troops to attack, they remain still. Disillusioned with his increasingly unstable leadership, the troops finally accuse Washizu of the murder of Tsuzuki. For his treachery they turn on their master and begin firing arrows at him, also to appease Miki's son and Noriyasu. Washizu finally succumbs when one of the arrows leaves a mortal wound just as his enemies approach the castle gates. It is revealed that the attacking force is using trees cut down during the previous night to disguise and protect themselves in their advance on the castle.

Cast

| Actor | Character | Macbeth analogue |

|---|---|---|

| Toshiro Mifune | Washizu Taketoki (鷲津 武時) | Macbeth[1] |

| Isuzu Yamada | Washizu Asaji (鷲津 浅茅) | Lady Macbeth[2] |

| Takashi Shimura | Odakura Noriyasu (小田倉 則保) | Macduff[3] |

| Akira Kubo | Miki Yoshiteru (三木 義照) | Fleance[4] |

| Hiroshi Tachikawa | Tsuzaki Kunimaru (都築 国丸) | King Duncan[5] |

| Minoru Chiaki | Miki Yoshiaki (三木 義明) | Banquo[4][6] |

| Takamaru Sasaki | Lord Tsuzuki Kuniharu (都築 国春) | Malcolm[7] |

| Kokuten Kōdō | First General | |

| Ueda Kichijiro | Washizu's workman | |

| Eiko Miyoshi | Senior lady-in-waiting | |

| Chieko Naniwa | The Spirit of Spider's Web (物の怪の妖婆) | Three Witches[8] |

Production

Development

William Shakespeare's plays had been read in Japan since the Meiji Restoration in 1868,[8] though banned during World War II for not being Japanese.[9] Director Akira Kurosawa stated he had had an admiration for Shakespeare's Macbeth for a long time, and envisioned making a film based on it. He hoped to make one after his 1950 film Rashomon, but opted to wait when he learned Orson Welles was releasing a Macbeth film.[10]

Kurosawa believed that Scotland and Japan in the Middle Ages shared social problems and that these had lessons for the present day. Moreover, Macbeth could serve as a cautionary tale complementing his 1952 film Ikiru.[10]

The film combines Shakespeare's play with the Noh style of drama.[11] Kurosawa was an admirer of Noh, which he preferred over Kabuki. In particular, he wished to incorporate Noh-style body movements and set design.[12] Noh also makes use of masks, and the evil spirit is seen, in different parts of the film, wearing faces reminiscent of these masks, starting with yaseonna (old lady).[13] Noh often stresses the Buddhist doctrine of impermanence. This is connected to Washizu being denied salvation, with the chorus singing that his ghost is still in the world.[14] The film score's use of flute and drum are drawn from Noh.[15]

Originally, Kurosawa planned only to produce the film, and hand over the reins to another director. However, Toho, assessing the budget and seeing the film would be costly, insisted Kurosawa direct it himself.[16]

Filming

The castle exteriors were built and shot high up on Mount Fuji. The castle courtyard was constructed at Toho's Tamagawa studio, with volcanic soil brought from Fuji so that the ground would match. The interiors were shot in a smaller Tokyo studio. The forest scenes were a combination of actual Fuji forest and studio shots in Tokyo. Washizu's mansion was shot in the Izu Peninsula.[17]

In Kurosawa's own words,

It was a very hard film to make. We decided that the main castle set had to be built on the slope of Mount Fuji, not because I wanted to show this mountain but because it has precisely the stunted landscape that I wanted. And it is usually foggy. I had decided that I wanted lots of fog for this film... Making the set was very difficult because we didn't have enough people and the location was so far from Tokyo. Fortunately, there was a U.S. Marine Corps base nearby, and they helped a great deal; also a whole MP battalion helped us out. We all worked very hard indeed, clearing the ground, building the set. Our labor on this steep fog-bound slope, I remember, absolutely exhausted us; we almost got sick.[17]

Production designer Yoshirō Muraki said the crew opted to employ the color black in the set walls, and a lot of armor, to complement the mist and fog effects. This design was also based on ancient scrolls depicting Japanese castles.[16]

Washizu's death scene, in which his own archers turn upon him and shoot him with arrows, was in fact performed with real arrows, shot by knowledgeable and skilled archers. During filming, Mifune waved his arms, which was how the actor indicated his intended bodily direction. This was for his own safety, to prevent the archers accidentally hitting him.[18]

Release

In Japan, the film was released by Toho on 15 January 1957. It played at 110 minutes and brought in more revenue than any other Toho film that year.[19]

In the United States, the film was distributed by Brandon Films at 105 minutes and opened on 22 November 1961.[19] In Region A, The Criterion Collection released the film on Blu-ray in 2014, having released a DVD version 10 years before.[20]

Reception

Critical reception

In 1961, the Time review praised Kurosawa and the film as "a visual descent into the hell of greed and superstition".[21] Writing for The New York Times, Bosley Crowther called the idea of Shakespeare in Japanese "amusing," and complimented the cinematography.[22] Most critics stated it was the visuals that filled the gap left by the removal of Shakespeare's poetry.[23] U.K. directors Geoffrey Reeve and Peter Brook considered the film to be a masterpiece, but denied it was a Shakespeare film because of the language.[24] Author Donald Richie praised the film as "a marvel because it is made of so little: fog, wind, trees, mist".[15]

The film has received praise from literary critics despite the many liberties it takes with the original play. The American literary critic Harold Bloom judged it "the most successful film version of Macbeth".[25] Sylvan Barnet writes it captured Macbeth as a strong warrior, and that "Without worrying about fidelity to the original," Throne of Blood is "much more satisfactory" than most Shakespeare films.[26]

In his 2015 Movie Guide, Leonard Maltin gave the film four stars, calling it a "Graphic, powerful adaptation".[1] Throne of Blood currently holds a 98% "Certified Fresh" rating on the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, based on 42 reviews.[27]

Accolades

| Award | Date of ceremony | Category | Recipient(s) | Result | Ref(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kinema Junpo Awards | 1958 | Best Actress | Isuzu Yamada | Won | [19] |

| Mainichi Film Awards | 1957 | Best Actor | Toshirô Mifune | Won | [28] |

| Best Art Direction | Yoshirō Muraki | Won | |||

Legacy

Roman Polanski's 1971 film version of Macbeth has similarities to Throne of Blood, in shots of characters setting down twisted roads, set design, and using music to identify locations and psychological conditions.[29] Toshiro Mifune's death scene was the source of inspiration for Piper Laurie’s death scene in the 1976 film Carrie,[30] in which knives are thrown at her, in this case by character Carrie White using her psychic powers. Kurosawa returned to adapting Shakespeare, choosing the play King Lear for his 1985 film Ran, and again moving the setting to feudal Japan.[31]

Throne of Blood is also referenced in the anime film Millennium Actress (2001) in the form of the Forest Spirit/Witch.[32] It was adapted for the stage by director Ping Chong, premiering at the 2010 Oregon Shakespeare Festival in Ashland, Oregon.[33]

References

- 1 2 Maltin 2014.

- ↑ Richie 1998, p. 117.

- ↑ Burnett 2014, p. 67.

- 1 2 Phillips 2013, p. 31.

- ↑ Davies 1994, p. 161.

- ↑ Hatchuel 2013.

- ↑ McDougal 1985, p. 253.

- 1 2 Buchanan 2014, p. 73.

- ↑ Buchanan 2014, p. 74.

- 1 2 Richie 1998, p. 115.

- ↑ Prince 1991, p. 142–147.

- ↑ McDonald 1994, p. 125.

- ↑ McDonald 1994, p. 129.

- ↑ McDonald 1994, p. 130.

- 1 2 Lei 2009, p. 90.

- 1 2 Richie 1998, p. 122.

- 1 2 Richie, Donald (1964). "Kurosawa on Kurosawa". Sight and Sound.

- ↑ Blair, Gavin J. (16 March 2016). "1957: When Akira Kurosawa's 'Throne of Blood' Was Ahead of Its Time". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 10 December 2016.

- 1 2 3 Galbraith 2008, p. 129.

- ↑ Baumgarten, Marjorie (8 January 2014). "DVD Extra: 'Throne of Blood'". The Austin Chronicle. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- ↑ "Cinema: Kurosawa's Macbeth". Time. 1 December 1961. Retrieved 9 December 2016.

- ↑ Crowther, Bosley (23 November 1961). "Screen: Change in Scene:Japanese Production of 'Macbeth' Opens". The New York Times. Retrieved 9 December 2016.

- ↑ Yoshimoto 2000, p. 268.

- ↑ Lei 2009, p. 88.

- ↑ Bloom 1999, p. 519.

- ↑ Barnet 1998, p. 197-198.

- ↑ "Throne of Blood (1957)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 9 December 2016.

- ↑ "12th (1957)". Mainichi Film Awards. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- ↑ Kliman 2004, p. 195.

- ↑ Zinoman 2011.

- ↑ Davies 1994, p. 153.

- ↑ Cavallaro 2009, p. 17.

- ↑ Isherwood, Charles (11 November 2010). "Sprawling Cinema, Tamed to a Stage". The New York Times. Retrieved 10 December 2016.

Bibliography

- Barnet, Sylvan (1998). "Macbeth on Stage and Screen". Macbeth. A Signet Classic.

- Bloom, Harold (1999). Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human. New York. ISBN 1-57322-751-X.

- Buchanan, Judith R. (2014). Shakespeare on Film. Routledge. ISBN 131787496X.

- Burnett, Mark Thornton (2014). "Akira Kurosawa". Great Shakespeareans Set IV. 14-18. London, New Delhi, New York and Sydney: Bloomsbury. ISBN 1441145281.

- Cavallaro, Dani (2009). Anime and Memory: Aesthetic, Cultural and Thematic Perspectives. Jefferson, North Carolina and London: McFarland & Company Publishers. ISBN 0786453478.

- Davies, Anthony (1994). Filming Shakespeare's Plays: The Adaptations of Laurence Olivier, Orson Welles, Peter Brook, Akira Kurosawa. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521399130.

- Galbraith, Stuart IV (2008). The Toho Studios Story: A History and Complete Filmography. Lanham, Maryland, Toronto and Plymouth: The Scarecrow Press. ISBN 1461673747.

- Hatchuel, Sarah; Vienne-Guerrin, Nathalie; Bladen, Victoria, eds. (2013). "The Power of Prophecy in Global Adaptations of Macbeth". Shakespeare on Screen: Macbeth. Publication Univ Rouen Havre. ISBN 9791024000404.

- Kliman, Bernice W. (2004). Macbeth (Second ed.). Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press. ISBN 0719062292.

- Lei Jin (2009). "Silence and Sound in Kurosawa's Throne of Blood". Shakespeare in Hollywood, Asia, and Cyberspace. West Lafayette, Indiana: Purdue University Press. ISBN 1557535299.

- Maltin, Leonard (September 2014). Leonard Maltin's 2015 Movie Guide. Penguin Group.

- McDonald, Keiko I. (1994). Japanese Classical Theater in Films. London and Toronto: Associated University Presses. ISBN 0838635024.

- McDougal, Stuart Y. (1985). Made into Movies: From Literature to Film. Holt, Rinehart, and Winston.

- Phillips, Chelsea (2013). "I Have Given Suck". Shakespeare Expressed: Page, Stage, and Classroom in Shakespeare and His Contemporaries. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 1611475619.

- Prince, Stephen (1991). The Warrior's Camera: The Cinema of Akira Kurosawa. Princeton University Press.

- Richie, Donald (1998). The Films of Akira Kurosawa. Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press. ISBN 0520220374.

- Yoshimoto, Mitsuhiro (2000). Kurosawa: Film Studies and Japanese Cinema. Duke University Press. ISBN 0822325195.

- Zinoman, Jason (2011). "He Likes to Watch". Shock Value: How a Few Eccentric Outsiders Gave Us Nightmares, Conquered Hollywood, and Invented Modern Horror. New York: The Penguin Press. ISBN 1101516968.

External links

- Throne of Blood on IMDb

- Throne of Blood at AllMovie

- Program note from the 1957 San Francisco International Film Festival

- Throne of Blood (in Japanese) at the Japanese Movie Database

- Throne of Blood: Shakespeare Transposed an essay by Stephen Prince at the Criterion Collection