Oregon Shakespeare Festival

| Oregon Shakespeare Festival | |

|---|---|

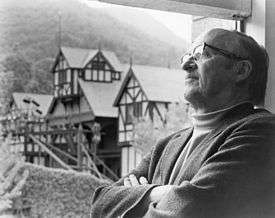

Angus Bowmer and the outdoor theatre, the keystone of the Oregon Shakespeare Festival he created. | |

| Genre | Repertory theatre |

| Begins | Each February |

| Ends | Each November |

| Frequency | annual |

| Location(s) | Ashland, Oregon |

| Inaugurated | 1935 |

| Attendance | 400,000 (annual) |

| Budget | $32 million (annual) |

| Website | osfashland.org |

The Oregon Shakespeare Festival (OSF) is a regional repertory theatre in Ashland, Oregon, United States. Each year, the Festival produces eleven plays, usually from three to five by Shakespeare and the remainder by other playwrights, on three stages during an eight-month season beginning in mid-February. From its inception in 1935 through the end of the 2017 season (excepting the war years 1941–1946) the Festival has presented all 37 of Shakespeare's plays a total of 312 times and beginning in 1960, 341 non-Shakespeare plays for a total of over 30,000 performances. It has completed the complete Shakespeare canon of 37 plays in 1958, 1978, 1997, and 2016.[1] The Festival welcomed its millionth visitor in 1971, its 10-millionth in 2001, and its 20-millionth visitor in 2015. A complete list by year and theater is available at the Main article: Production history of the Oregon Shakespeare Festival.

Overview

A season at OSF consists of a wide range of classic and contemporary plays produced in three theatres. Three plays are staged in the outdoor Allen Elizabethan Theatre, three in the Thomas Theatre, and five in the Angus Bowmer Theatre. OSF also provides a broad range of educational programs for middle schools, high schools, college students, teachers, and theatre professionals. While OSF has produced non-Shakespearean works since 1960, each season continues to include three to five Shakespeare plays. Since 1935, it has staged Shakespeare's complete canon three times, completing the first cycle in 1958 with a production of Troilus and Cressida and completing the second and third cycles in 1978 and 1997. Since 2000, there has also been at least one new work each season from playwrights such as Octavio Solis and Robert Schenkkan.

Each year, the Festival offers 750 to 800 performances from February through late October or early November, to a total audience of about 400,000. The company consists of about 675 paid staff and 700 volunteers.[2] The Oregon Shakespeare Festival is listed as a Major Festival in the book Shakespeare Festivals Around the World.[3]

Green Show

In addition to the plays, beginning in 1951 a free outdoor "Green Show" drawing audiences of 600 to 1200, often including non-playgoers, has preceded the evening plays from June through October from a modular steel stage with a sprung floor for the dancers, a removable wheelchair ramp for performers with disabilities, and built-in storage facilities that eliminate carting equipment from and to distant storage facilities six days a week. Originally, it offered Elizabethan music and dancers. From 1966 till 2007, it consisted of three Renaissance-themed shows in rotation inspired by the plays showing in the Allen Elizabethan Theatre. Live music was supplied by the Terra Nova Consort and other guest musicians and modern dance was performed by Dance Kaleidoscope. In 2008, the Green Show was revamped. The nightly shows now vary widely with performers such as a dance group from Mexico or India one night, clowns doing ballet on stilts the next, and a classical music quartet on another. A fire show, juggler, or magician might be seen along with improv, metal, or rock-n-roll variations on Shakespeare. Individual performers, groups, choirs, bands, and orchestras may present Afro-Cuban, baroque, blues, classical, contemporary, cowboy, funk, gospel, hip-hop, jazz, mariachi, marimba, poetry, marionette, renaissance, or salsa, sometimes combined in unexpected ways.[1][4][5]

History

In 1893, the residents of Ashland built a facility to host Chautauqua events. In its heyday, it accommodated audiences of 1,500 for appearances by the likes of John Philip Sousa and William Jennings Bryan during annual 10-day seasons.[6]

In 1917, a new domed structure was built at the site, but it fell into disrepair after the Chautauqua movement died out in the 1920s. In 1935, the similarity of the remaining wall of the then roofless Chautauqua building to Elizabethan theatres inspired Southern Oregon Normal School drama professor Angus L. Bowmer to propose using it to present plays by Shakespeare. Ashland city leaders loaned him a sum "not to exceed $400" (approximately equivalent to $7100 in 2014) to present two plays as part of the city's Independence Day celebration. However, they pressed Bowmer to add boxing matches to cover the expected deficit. Bowmer agreed, feeling such an event was in perfect keeping with the bawdiness of Elizabethan theatre, and the performances went forward. The Works Progress Administration helped construct a makeshift Elizabethan stage on the Chautauqua site,[7] and confidently billing it as the "First Annual Oregon Shakespearean Festival", Bowmer presented Twelfth Night on July 2 and July 4, 1935, and The Merchant of Venice on July 3, directing and playing the lead roles in both plays himself.[7] Reserved seats cost $1, with general admission of $.50 for adults and $.25 for children (approximately equivalent to $17, $8.50 and $4.25 in 2014). Ironically, the profit from the plays covered the losses the boxing matches incurred.[8]

The Festival has continued ever since (excepting 1941–1946 while Bowmer served in World War II), and quickly developed a reputation for quality productions. Angus Bowmer's first wife Lois served as art director, creating both costumes and scenery during the formative years of the Festival from 1935 to 1940 years.[1] In 1939, OSF took a production of The Taming of the Shrew to the Golden Gate International Exposition in San Francisco that was nationally broadcast on radio. The lead actress, learning at the last minute the broadcast would be to a national audience, suffered a panic attack, was rushed to the hospital and the stand-in took over. The scripts didn't arrive on the set until three minutes before air time. The Festival achieved widespread national recognition when, from 1951 to 1973, NBC broadcast abbreviated performances each year that were carried by more than 100 stations and, after 1954 on Armed Forces Radio and Radio Free Europe. The programs won favorable review from critics and people began to come from around the country. The programs led Life magazine to do a story on the Festival in 1957, bringing even more people to the plays. The NBC programs and the subsequent attention go a long way to explaining the mystery of how a tiny out-of-the-way timber town in the Northwest became a theatrical and tourist Mecca.[9]

Bing Crosby served as an honorary director of the festival from 1949 to 1951. Charles Laughton visited in 1961, saying "I have just seen the four best productions of Shakespeare that I have ever seen in my life." Laughton begged to play King Lear, but died in 1962 before he could fulfill the dream. Stacy Keach was a cast member in 1962 and 1963. Duke Ellington and his orchestra presented a benefit concert in 1966 that brought many luminaries to Ashland.[1]

1952 saw the birth of the tradition of closing the outdoor season with a ceremony in which many of company members enter the darkened theater carrying candles and a company member selected for the honor speaks Prospero's words from Act IV Scene I of the Tempest beginning, "Our revels now are ended. These our actors, As I foretold you, were all spirits and Are melted into air, into thin air…" On completion of the speech all extinguish the flames and file silently out of the theatre.[1]

The tradition of opening the outdoor season with a Feast of Will (initially the Feasting of the Tribe of Will) was initiated in 1956 in Lithia Park with Miss Oregon and then state senator Mark Hatfield attending.[1]

The City of Portland approached OSF in the late 1970s about joining the art scene there, leading to the building of a new center in Portland. In 1986, OSF was again approached about producing in the new Portland Center for the Performing Arts, leading to the launch in November 1988 of a season of five plays including Shaw's Heartbreak House and Shakespeare's Pericles, Prince of Tyre, the first of four productions that transferred to or from Ashland. At the invitation of the City of Portland, OSF established a resident theatre in the Portland Center for the Performing Arts in 1988 that spun off to independence in 1994 as Portland Center Stage. Those six seasons ran from November–April, allowing many company members to work in both cities. In 1990-1991 Portland imported rotating repertory from OSF, a company of 10 actors performing 43 roles.[1]

In 1986, the Festival received the President's Volunteer Action Award; in 1987 it initiated Daedalus, a fundraiser to help victims of HIV/AIDS that has continued annually ever since.[1]

A second theatre, the indoor Angus Bowmer Theatre (see below), opened in 1970, enabling OSF to expand its season into the spring and fall; within a year, attendance tripled to 150,000. Angus L. Bowmerretired in 1971, and leadership of the Festival passed to Jerry Turner, a respected actor/director and later a translator of Henrik Ibsen and August Strindberg, who served as artistic director until 1991. He widened the Festival repertory to production of classics by the likes of Molière, Ibsen, and Chekhov. By 1976, the festival was filling 99% of its seats while offering some 275 performances of eight plays each season. In 1977, the Festival opened a third theatre, dubbed the Black Swan (see below), in what originally was an auto dealership, and attendance reached 300,000. By 1979, the year that Bowmer died, the Festival was producing 11 plays a season, the number that has been standard ever since. In 1983 OSF won both its first Tony Award for outstanding achievement in regional theatre and the National Governors' Association Award for distinguished service to the arts, the first ever to a performing arts organization.[1]

The Oregon Shakespearean Festival was renamed the Oregon Shakespeare Festival in 1988. Turner retired in 1991 and actor/director Henry Woronicz took control from 1991 to 1996. When Woronicz left in 1996, OSF recruited Libby Appel from the highly respected Indiana Repertory Theatre, and a guest director at OSF from 1988 to 1991. She served as Artistic Director from 1996 through 2007. In 1997, the OSF-commissioned The Magic Fire was presented at the John F. Kennedy Center and named by Time among the year's best plays. In 2002, the Thomas Theatre (see below) replaced the Black Swan as the venue for small, experimental productions in a Black box theatre. In 2003, Time named OSF as the second best regional theatre in the United States (Chicago's Goodman Theater was first).[10]

Bill Rauch as artistic director

Current Artistic Director Bill Rauch succeeded Appel in 2008. Rauch was the co-founder and artistic director of the Cornerstone Theater Company in Los Angeles and had been a guest director at OSF for six seasons prior to his appointment. His vision includes making direct connections between classic plays and contemporary concerns, incorporating musicals into the annual selection of plays, exploring beyond the Western canon to incorporate Asian and African epics into the Festival, and reaching out to youth. While continuing to work with established playwrights, he has commissioned works by new ones, and has initiated the Black Swan Lab to develop new works for the stage. Each year, ten OSF actors are assigned to the Lab to work with Bill Rauch, OSF Dramaturg Lue Douthit, and Producer Sarah Rasmusen as one of their regular repertory assignments. In recognition of his work, he received the Margo Jones Award for his impact on American theatre in 2009 and the 2018 Ivy Behune Award from Actors Equity.[11]

Inspired by Shakespeare's canon of plays, Rauch initiated a 10-year program to commission of up to 37 new plays collectively called American Revolutions: the United States History Cycle. Under the direction of Alison Carey, the plays look at moments of change in America's past. Grants from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the Collins Foundation, the Edgerton Foundation, the Harold and Mimi Steinberg Trust, and the Paul G. Allen Family Foundation support American Revolutions. Through December 2016, 32 plays have been commissioned and ten of these have reached the stage, beginning with American Night: The Ballad of Juan Jose (2010). It was followed by Ghost Light (2011); The March (2011 at Steppenwolf Theatre Company); Party People and All the Way (2012); The Liquid Plain (2013); the sequel to All the Way, The Great Society (2014, commissioned by and co-produced with Seattle Repertory Theatre), Sweat (2015), Indecent (2015 at Yale Repertory Theatre and La Jolla Playhouse; 2016 at Vineyard Theatre; 2017 on Broadway), and Roe (co-produced with Arena Stage and Berkeley Repertory Theatre).

Through December 2014, All the Way has received seven awards including co-winner of the inaugural 2013 Edward M. Kennedy Prize for Drama Inspired by American History; the 2014 Tony Award for Best Play, the Drama Desk Award for Outstanding Play, the Drama League Award for Outstanding Production of a Broadway Play, the Outer Critics Circle Award for Outstanding New Play, the Elliott Norton Award for Outstanding Production by a Large Resident Theatre, and the IRNE Award for Best New Play, Large Theater. In addition, the 2014 Tony Award for best actor went to Bryan Cranston[12] for his portrayal of Lyndon Johnson in the Broadway production of All the Way.[13] Partnerships with Arena Stage, Berkeley Repertory Theatre, Center Stage, Company One, Guthrie Theater, Penumbra Theatre Company Playwrights Center, The Public Theater, Seattle Repertory Theatre and Steppenwolf Theatre Company ensure that the plays will reach beyond their original OSF audience. Time (insert reference to 6 December 2017 issue) magazine named Lynn Nottage's Sweat and Paula Vogel's Indecent #1 and #3, respectively, to their list of the "Top 10 Plays and Musicals of 2017", both originating as part of the American Revolutions project at OSF.[14]

In February 2018, the Oregon Shakespeare Festival announced that Rauch would be leaving after completing the 2019 season to become artistic director of the new Perelman Center at the World Trade Center in New York. [15]

Play On!

Columbia University Professor John McWhorter has pointed out that Shakespeare's language is no longer entirely ours. Granted, he says, with the help of notes and time to study them, you can work out the sense of some of the obscure dialogue, but not in a theatre in a matter of seconds while the action speeds by and the actors deliver the lines with all the urgency of the moment then move on. Its time, goes the argument of many scholars, for versions that will do for a contemporary English-speaking public what has been done for much of the world where Shakespeare is performed in the native language of the audience—make every word intelligible.[16]

Play on! is an OSF project being carried out by 36 playwrights paired with dramaturgs working in concert with 17 different theatres and academic institutions commissioned to translate all 39 plays attributed to Shakespeare into contemporary modern English by 31 December 2018. Each playwright is asked to respect the language, meter, rhythm, metaphor, image, rhyme, rhetoric, and emotional content of the original. The goal is 39 unique side-by-side companion translations that are both performable and useful reference texts for classrooms and productions.[16]

While each playwright will take his or her own approach, Kenneth Cavander, the playwright who undertook and completed this task for Timon of Athens felt that the trick was to leave what is immediate and alive to our ears in the original untouched and only elsewhere to unpack whatever might hinder the free flow of the story in a way that is clear, not over-reverent, and above all, actable, so that the result is clear and compelling to a contemporary audience while preserving the spirit of the original.[16]

Economic importance

In 2013, 108,388 individuals bought 407,787 tickets, seeing an average of 3.76 plays each. Of these, 92,234 people were visitors to the area spending $54,534,565 beyond the price of their theater tickets. Added to the $32,233,543 in actual Festival expenditures, the direct contribution to the local economy in 2013 was $86,768,108. In 2015, 103,946 individuals bought 390,380 tickets, seeing an average of 3.3 plays each. Of these, 88,784 people were visitors to the area spending $55,332,927 beyond the price of their theater tickets. Added to the $35,182,783 in actual Festival expenditures, the direct contribution to the local economy in 2015 was $90,515,710. The estimated total contribution based on the multiplier effect brought total impact to $251,627,515 in 2013 and to $262,495,558 in 2014. The multiplier effect measures how often each dollar received is spent partly on further local goods and services. For OSF, 2.9 is the estimated multiplier.[17][18]

Attendance in 2014 at 794 performances of eleven plays was 398,289, 88% of capacity. Attendance in 2015 at 786 performances of eleven plays was 390,387, 87% of capacity. In 2017, overall attendance at 795 performances was 381,378, 82% of capacity, generating $21.9 million in ticket sales. The difference was accounted for by the eight fewer scheduled performances, variations in seating configurations, cancellation of five outdoor performances in 2015 and of nine outdoor performances in 2017 due to smoke from forest fires.[19][20]

The Oregon Shakespeare Festival is an active community citizen. It participates each year in Ashland's Martin Luther King celebration, Juneteenth celebration of the Emancipation Proclamation, and Fourth of July Parade.[21] The Green Show (see above) and Hip-Hop Poetry Open Mic are free. The Daedalus Project is an annual fund-raising event managed by company members since 1988 in support of HIV/AIDS charitable organizations. It features a morning fun run, an afternoon play reading, an "arts and treasures" sale and an evening variety show and underwear parade.

In 2016, the Festival hosted the fifth biennial national Asian American Theater Conference and Festival. In addition to a full slate of conference sessions during the week, the event included six original plays, five play readings, and three Green Shows (see above). Participants also had an opportunity to see several regular Festival performances, two of which had an Asian setting and one an Asian-American theme.[22]

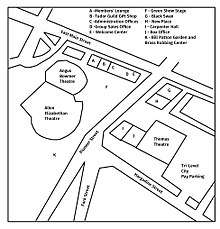

OSF campus

The Oregon Shakespeare Festival occupies a 4-acre (16,000 m2) campus adjacent to Lithia Park and the Plaza in Ashland, Oregon. The primary buildings are the three theatres, Carpenter Hall, and the Camps, Pioneer, and Administration buildings, all surrounding an open central court, locally known as "The Bricks" that ties everything together into an architecturally coherent whole and facilitates movement. It also provides a stage for the nightly Green Shows (see above) from June through September. Other facilities include the Black Swan, which serves as a laboratory for the development of new plays, the production facility, the costume shop, classrooms, and the Hay Patton Rehearsal Center. Other buildings are off campus.

Allen Elizabethan Theatre

The Allen Elizabethan Theatre has evolved since the founding of the Shakespeare Festival when the first performance of Twelfth Night was presented on July 2, 1935.

Original Elizabethan Theatre

The design for the first outdoor OSF Elizabethan Theatre was sketched by Angus L. Bowmer based on his recollection of productions at the University of Washington in which he had acted as a student. Ashland, Oregon obtained WPA funds in 1935 to build it within the 12-foot-high (3.7 m) high circular walls that remained in the roofless shell of the abandoned Chautauqua theatre. Bowmer extended the walls to reduce the stage width to fifty-five feet, and painted the extensions to resemble half-timbered buildings. He designed a thrust stage—one projecting toward the audience—with a balcony. Two columns helped divide the main stage into forestage, middle stage, and inner stage areas. Illustrating the improvised nature of it all, actors doubled as stage hands, stage lighting was housed in coffee cans, and string beans were planted along the walls to improve sound quality! Fifty cent general admission seating was on benches just behind the one-dollar reserved seating on folding chairs. This theatre was torn down during World War II.[23]

Second Elizabethan Theatre

The second outdoor Elizabethan Theatre was built in 1947 from plans drawn up by University of Washington drama professor John Conway. The main stage became trapezoidal, with entries added on either side, and windows added above them flanking the balcony stage. A low railing gave a finished appearance to the forestage. Chairs arranged to improve sight lines replaced bench seating. Backstage areas were added gradually and haphazardly, until the ramshackle result was ordered torn down as a fire hazard in 1958.[23]

Current Allen Elizabethan Theatre

The next year saw the opening of the current outdoor theatre, whose name was changed from Elizabethan to Allen Elizabethan Theatre in October, 2013.[24] Patterned on London's 1599 Fortune Theatre and designed by Richard L. Hay, it incorporated all the stage dimensions mentioned in the Fortune contract. The trapezoidal stage was retained but the façade was extended to three stories, resulting in a forestage, middle stage, inner below, inner above (the old balcony), and a musicians' gallery. The wings were provided with second-story windows. Each provides acting areas, creating many staging possibilities. A pitched, shingled roof enhances the half-timbered façade. A windowed gable was extended from the center of the roof to cover and define the middle stage. Just before each performance, an actor opens the gable window, and in keeping with Elizabethan tradition signaling a play in progress, runs a flag up the pole to the sound of a trumpet and doffs his cap to the audience.

The result is an approximate replica of the Fortune Theatre. The known but incomplete dimensions apply only to the stage. The original specifications sometimes say no more than "to be built like the Globe," for which there are no plans or details. The remotely operated lighting, on scaffolding on either side of the stage, of course did not exist in the original and the current site rather than the original architecture determines the shape of the auditorium. Twelve hundred seats in slightly offset arcs ascend the original hillside, giving an excellent view of the stage from each seat. The old Chautauqua theatre walls, now ivy-covered, remain as the outer perimeter of the theatre.

The $7.6 million Paul Allen Pavilion was added in 1992. It houses a control room, and audience services including infrared hearing devices, blankets, pillows and food and drink, which are allowed in the auditorium. Several hundred seats were moved to a balcony and two boxes, further improving sightlines and acoustics. Vomitoria (colloquially "voms"), the traditional name for entryways for actors from under the seating area, were added and the lighting scaffolds were eliminated.[25]

Each year, three plays are offered in rotation Tuesdays through Sundays in the Allen Elizabethan Theatre from late June to early October.

Angus Bowmer Theatre

An April 1968 report by the Bureau of Business and Economic Research of the University of Oregon pointed to the lost opportunity represented by turning away thousands of people by the Oregon Shakespeare Festival each year. It further noted that the Festival had become an important economic engine for southern Oregon, and recommended addition of an indoor theatre. This led the City of Ashland to apply to the Economic Development Administration of the Department of Commerce in Fall 1968 for a $1,792,000 project grant with the Angus Bowmer Theatre as the keystone. The plan also called for a parking building, a remodeled administration building and box office, a scene shop and exhibit hall that later would become the OSF Black Swan, landscaping, and street realignment. $896,000 was approved in April 1969, to match an equal amount to be raised through private donations. The fund drive quickly exceeded its goal and ground for the new theatre was broken on December 18, 1969.

The theatre was ready just five months later and opened with a production of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead, selected to recognize the Shakespearean origin of the Festival but to signal that the Festical also was ready to broaden its horizons by incorporating modern plays into its repertoire. Reinforcing that signal, The Fantasticks and You Can't Take it with You were also presented during that first six-week season.

The Angus Bowmer Theatre seats between 592 and 610 patrons depending on configuration. Although about half the size of the outdoor theatre, it more than doubled audience capacity by making it possible to hold matinee performances and to extend the season into spring and fall.

The design by Richard L. Hay with architects Kirk, Wallace and McKinley of Seattle and contractor Robert D. Morrow, Inc., Salem, Oregon was at once basic, flexible, functional and innovative. All seats are within 55 feet (17 m) of the stage, arranged with only two side aisles and wide spaces between rows. Dark colors resist reflection and draw the eye to the stage. The forestage is on a hydraulic lift system that can emulate the thrust stage of the OSF Allen Elizabethan Theatre, form a more conventional proscenium front, move below auditorium floor level to form an orchestra pit, or drop two stories for storage of equipment or scenery. The walls of the auditorium can swing in to close down the playing area or open to accommodate larger productions.[26]

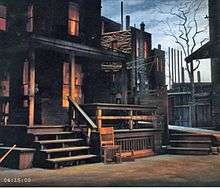

Illustrating these characteristics, the first picture is the set for August Wilson's Fences. The second, taken two hours later, is the set for the ancient Hindu classic The Clay Cart. Stage crews for the two indoor theatres must complete set changes of this scope six days a week between the end of a matinee and the "call" before the evening curtain (the outdoor stage changes daily). This illustrates the nature of true repertory theater, which allows the playgoer to see different plays on the same day on the same stage, but requires designing and making sets to withstand constant rapid assembly, disassembly and return to accessible storage to await the next change of set.

In what then Executive Director Paul Nicholson called the biggest crisis in the history of the Festival, a crack was discovered in the seventy-foot long, six and one-half foot high main ceiling support beam of the Bowmer Theatre two hours before the 18 June 2011 matinee. Shows were immediately relocated to other venues as work progressed to repair the beam. A 598-seat tent, "Bowmer in the Park", was erected as a temporary replacement venue. A single set was designed and built to serve four very different shows, and the shows themselves were re-staged while keeping the artistic vision of each as intact as possible. Thirty-one performances were given in the tent and averaged 82% of capacity generating approximately $650,000 in revenue against approximately $800,000 for the tent itself, $1,000,000 in lost revenue from ticket returns, and $330,000 in repair costs. The Bowmer reopened on 2 August, a month ahead of the initial estimate. The Festival filed an insurance claim for $3.58 million and received checks in March 2012 for $330,000 to cover the cost of repairs and $2.984 million covering much of the lost revenue, leaving about $200,000, primarily representing the cost of the temporary tent theater itself, unresolved.[27][28][29][30][31][32]

Black Swan

The Black Swan (G on the OSF campus map above) served as the Festival's third theatre from 1977 to 2001. The building, originally an automobile dealership, was bought in 1969 as a scene shop and rehearsal hall. Company members began using it to stage "midnight" readings for one another. They invited friends who brought other friends. Artistic Director Jerry Turner recognized the opportunity to take risks with unconventional staging and subjects, and called for its development as a third OSF theatre. Fitting a theatre into the existing building was challenging. It could hold only 138 seats, all within five rows of the stage. There had to be, as designer Richard Hay put it, a "certain amount of tucking and squeezing." Each director had to solve the problem of an immovable roof support in the middle of the stage. For instance, in one production, it became a crucifixion after a horizontal piece added, . The theatre reverted to its earlier roles in 2002 when it was replaced by the New Theater, now renamed the Thomas Theatre. Among those roles are rehearsal space, meeting and audition rooms, classes, and since 2011 as a home for the Black Swan Lab (see above).

Thomas Theatre

The limitations stemming from adapting an existing building as the Black Swan led to the design and building of a third theatre that provided flexible seating and increased capacity while maintaining the intimacy of the Black Swan.[1] Opened in March 2002 and originally named the New Theatre, it was renamed the Thomas Theatre in 2013 as a result of a generous $4.5 million gift from a group of donors. The name is in recognition of long-time OSF development director Peter Thomas who died in March 2010. The Thomas Theatre expands the possibilities for experiment and innovation while maintaining the intimacy of the Black Swan, no seat being more than six rows from the stage. Richard L. Hay designed the theatre space. Architects Thomas Hacker and Associates of Portland designed the building. The contractor was Emerick Construction, and acoustical engineering was provided by Dohn and Associates. The seats can be arranged in three configurations. In arena mode, a stage of 663 square feet (61.6 m2) is surrounded on all four sides by 360 seats. In three-quarter thrust mode, a 710-square-foot (66 m2) stage is surrounded on three sides by 270 seats, and in avenue mode, a 1,236-square-foot (114.8 m2) stage provides 228 seats on two sides. There is a trap room under the stage and a fly loft at one end. A computer controls 300 circuits and over 400 lights of various types. The remainder of the building is given over to downstairs and upstairs lobbies, concessions, access distribution, archives (see below), storage, laundry room, green room, quiet room, warm-up room, dressing space for 18 actors, showers/restrooms, costume and wig rooms, stage manager's office, maintenance space, and storage for props and set pieces.[33]

Other buildings

The Box Office (J on the OSF campus map above) is on the same courtyard as the Thomas Theatre. The Festival acquired the Administration Building (C) in April 1967. Forming the northern boundary of the campus, the building houses the Group Sales Office (D), artistic, business, communication, education, human resources, development, community productions, mailroom, and an annex to the costume shop. The Festival Welcome Center (E), on the northern side of the building facing Main Street, offers information about OSF and Ashland, houses a small rotating exhibit of costumes from past shows, and adjoins the Margery Bailey Room, otherwise known as the Education Center. The adjacent Camps Building (A) houses the members' lounge, marketing offices, and a meeting room.

Just off the courtyard, the Pioneer Building houses the Festival's costume shop. The staff of over 60 creates the costumes and accessories in three main studios on the lower floor of the building and in an extension of the Administration Building.[2] Also in this area are offices and fitting rooms for the costume designers and costume design assistants, a costume props area and a vented paint room. Upstairs is a dye room, lounge, laundry, storage room, and office. During the height of costume production each season, a wig shop and additional studio is open in the basement of the Angus Bowmer Theatre.

The Festival acquired Carpenter Hall (I) in October 1973, renovating it to accommodate lectures, concerts, rehearsals, meetings and Festival and community events. The Bill Patton Garden (K) provides the venue for free informal summer noon talks by OSF actors and staff. The Tudor Guild, a separate non-profit corporation, operates the Tudor Guild Gift Shop (B) and Brass Rubbing Center (K) where visitors can make rubbings of facsimiles of 55 historic English brasses under expert guidance. Just off campus, a purpose-equipped fitness center is staffed by two professional trainers who help prepare actors for physically demanding roles that often require acrobatics, fights, and pratfalls and monitored during additional open hours by a volunteer.

The Festival completed a $7.2 million purpose-built 71,544-square-foot (6,646.7 m2) production facility in neighboring Talent, Oregon, in November 2013 that is home to a multi-function staff of 40. The building houses custom-designed technologically advanced set and prop construction and scene painting facilities. The scene shop has an extensive pit area that precisely duplicates the trap doors in the theaters themselves, allowing for precise sizing, testing of assembly and disassembly, and automating elevator cues. Lighting in the painting areas duplicates that in the theaters, guaranteeing desired colors. The building also houses OSF's costume rental business, which has over 50,000 costumes and over 15,000 costume props such as armor, crowns, and wigs available for rent by other theaters, television and movie producers, and corporations.[34]

With the removal of the scene construction shop in 2014 from its location in a building a block from the Festival campus to the new Production Building (see above), a thirteen-month transformation began of the building into the Hay-Patton Rehearsal Center by demolishing everything except the masonry exterior and the steel framework and raising the second floor three feet. Following a plan developed by Ogden Roemer Wilkerson Architecture carried out by Adroit Construction at a cost of $4.4 million, it hosted its first rehearsal on 29 December 2015. The building is equipped with a sophisticated sound system and has six rehearsal halls, three of them some 3,000-square-foot (280 m2), sufficient precisely duplicate any of the three Festival theatres, and one which matches the Thomas Theatre stage. All six include fully sprung floors to protect actors' joints when dancing, rehearsing stage combat, or similar physical activities. The LED lighting system is zoned and dimmable, the ceilings have steel tracks which allow for suspension of scenery, lights, loudspeakers and even people. Some have special features such as small conversation areas and dance-style mirrors. Other features include a stage management office, a recording studio, a movement studio focused on the Feldenkrais Method, a voice studio for work on vocal technique, stamina, and dialect; a loading dock, a conference room, showers, two warmup spaces that double as small meeting rooms, two green rooms equipped with refrigerator, storage cases, sink, dishwasher, and tables (custom-made by the prop shop) and chairs.[35][36]

Organization

OSF is a non-profit corporation managed under US and Oregon law by a 32-member Board of Directors nominated and elected for eight-year terms. The endowment has a net worth in excess of $30 million that returns about $1.2 million to support the annual operating budget. It is managed by seven trustees who are selected for five-year terms by the Board of Directors.[37]

OSF is supported in part by corporate and individual donors through direct support of individual plays and annual non-voting memberships. These are offered at nine levels, each with its own privileges beginning with basic memberships for $75 which includes access to the member's lounge and a 10% discount in the Tudor Guild shop. Some 750 who contribute $1250-$2999 a year are designated Producer members, enjoying beyond all the benefits of the previous category, two complimentary tickets to plays, twice weekly coffees during which a cast member is interviewed, and three events each including three discussions on aspects of the year's productions and a dinner (at additional cost) with the actors. Additional benefits accrue to 175 Producer's Circle members who contribute $3000-$5999 in a year, to upward of 80 Chautauqua Guild and Chautauqua members who contribute $6000-$24,999, while those contributing $25,000 or more annually join the Artistic Director's Circle at one of four levels.[38]

Nearly 400 (many of whom also are annual members) who have supported the Festival through planned gifts are members of the Southampton Society, named for the Earl of Southampton who was Shakespeare's great patron. They are invited to one three-day event each season similar to the three for Producer members described above. Finally, some 150 people join the Bowmer Society annually providing partial support of the educational efforts of the Festival, described below.[39]

Professional staff

The OSF professional staff is organized into administrative, artistic, education, and production sections.

The administrative staff of approximately 125 is supervised by Executive Director Cynthia Rider (2013-) who follows Paul Nicholson (1995-2012) and William Patton (1955-1995). The Director of Finance and Administration supervises the physical plant (custodial services, maintenance, and security), accounting, mail room, and receptionists. The Director of Marketing and Communication supervises the box office, membership services, archives (see below), publications and media, marketing, and audience services, which itself includes house managers, ushers, concessions, and access staff for handicapped patrons (see below). The Director of Development supervises institutional giving and major gifts. The Director of ITS manages information technology. The Director of Human Resources manages employees, volunteer and events programs (see below), safety, and a professional development program called FAIR (Fellowships, Assistantships, Internships, and Residencies) that provides students aspiring to a career in theater with direct experience of best practices across all aspects of professional theatre. Fellows work directly with senior management while expanding their personal networks. Three residencies varying from four to eleven months are exclusive to the Dramaturgy and Literary Management Department. Twenty-five to thirty Assistantships annually provide hands-on opportunities in virtually every area of the organization by pairing recipients with an appropriate OSF staff member for an average of three months. Finally, 15-20 unpaid Internships of two to four months annually provide emerging artists and administrators with hands-on experience by pairing them with a Festival staff member in the assistant's area of interest. Internships may fulfill academic requirements determined by recipient's home academic institution.[40]

Artistic Director Bill Rauch (see above) leads a staff consisting of approximately 450. The Artistic Director selects the plays and directors for each season, and chooses the actors, who number between 90 and 120, and the musicians and dancers who number approximately 25. The Associate Artistic Director, in turn, supervises scenic, lighting, and costume design, Fight Director and the dramaturgs.

A Voice and Text Director is assigned to every play from pre-production through the opening performance. OSF employs two full-time voice and text directors and one or two guest artists each year to meet the demand for these specialists. They help the actors and directors craft vocal choices that will be theatrically effective and sustainable through the run of the show. This can involve work on posture, breath support, resonant placement, muscularity of articulation and screaming technique. They also work with the actors on the text of the play, often in one-on-one sessions. This can include examination of meter, rhythm, sound patterning such as alliteration and rhyme, imagery, and rhetorical structure and devices such as antithesis and repetition. When required, they coach the actors in accents and dialects based on samples of native speakers and work with each actor to find a sound that is as authentic as possible to the character's background but also intelligible in a contemporary theatrical context and conducive to that individual's acting process.

Once the plays have opened, the resident voice and text staff is on hand to help actors with vocal challenges that may arise, attend periodic performances to give maintenance notes, work with understudies, teach voluntary voice classes to the acting company, provide ongoing professional development support in the form of project or individual session work, and participate in play selection and workshops for upcoming seasons.

The production staff of approximately 125 is responsible for costumes, lighting, properties, scenery, sound, and stage operations. Costumes are produced by a staff of about 60 (artisans, cutters, designers, dyers, first hands, hair and wig specialists, stitchers, technicians, and wardrobe managers). Scenery is built by a staff of technicians, carpenters, a welder, an engineer and a buyer and moved by a crew of 24 stagehands; lighting staff number eight, and sound and properties each are managed by staffs of six each. A production stage manager, eight stage managers and three production managers ensure the smooth operation of the three theatres and a deck manager coordinates the Green Show.

Reflecting the profession of Festival founder Angus Bowmer, a professor of English at the then Southern Oregon Normal School (now Southern Oregon University), education has played an important role at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival from its inception. Under the direction of Joan Langley, the full-time education staff of nine includes the director, both in-residence and outreach program managers and coordinators, a curriculum specialist, and resident teaching artists. The goal is to inspire a lifelong relationship to theater and the works of Shakespeare by offering educational experiences that support each season's plays to a diverse range of students, teachers, and audiences.[41]

Thus, the Festival provides a broad range of educational programs for a wide range of ages and interests. The initial focus was on college students and the Institute for Renaissance Studies was formed to meet their needs. The Festival offered short courses, lectures, readings, concerts, and exhibits focused on the plays of the season. Participation was open to all Festival company members and audiences, either for college credit from several universities, or for audit. Coursework was supported by a collection of Renaissance and late-medieval books, manuscripts, and prints now housed in the Southern Oregon University's Hannon Library.

Programs specifically for teachers include the weekend "Inside Shakespeare" and the five-day retreat, "Shakespeare in the Classroom" that emphasizes innovative and pedagogical methods to help teachers make the works of Shakespeare involving and accessible to contemporary students.[42]

The completion of the indoor Angus Bowmer Theatre in 1971 and the subsequent expansion of the Festival season into the school year enabled an increasing variety of educational programs for middle and high school students. Students visiting the Festival itself are the recipients of some 55,000 discounted tickets each year. Some 900 workshops offered each year by OSF actor-teachers enhance the educational value of their visits. The Bowmer Project for Student Playgoers (initiated in 1996) prepares local teachers to teach plays and includes tickets to a performance, a back-stage tour, and a post-show discussion with one of the actors. Each year since 1981, OSF has offered residential Summer Seminars for High School Juniors that enroll 65 students in a two-week program during which they see several plays and learn about on-stage technique and theatre management.

For those unable to come to the Festival, six pairs of actors participate in the School Visit Program, initiated in 1971, which now reaches some 60,000 students primarily in four states although it has made occasional visits to eight others. Each one-day visit includes two 50-minute performances and one two-hour or two one-hour workshops. Performances are a condensed version of one Shakespeare play, selected scenes from Shakespeare illustrating a single theme, or a combination of Shakespeare and other literature selected to meet the needs of the school being visited.[43]

Programs of different lengths and formality to meet the needs and interests of adults include Wake Up With Shakespeare, Shakespeare Comprehensive, Festival Noons, Prefaces, Prologues, Park Talks, Road Scholars, and "Unfolding Seminars." [44]

Finally, OSF's Development Department offers educational opportunities through its tours offered in late Fall, often on cruise ships such as Queen Mary 2. Past tours have included two to England focused on Shakespeare, one to Greece and Turkey focused on the beginnings and history of theater, and one along the coasts of France and Spain and to the Canary Islands. These tours feature an intensive schedule of lectures and interactive workshops with four to eight OSF staff and actors, as well as visits to local attractions.[45]

The OSF website contains information on current educational programming.

Access Service Program

Audience Services offers a full range of programs and services for patrons with disabilities. For blind and visually impaired patrons, the Festival has six professional audio describers on staff who provide live audio description for every performance of every play with two weeks advance notice. Braille and large print playbills are available for all productions. Service animals are always welcome. For deaf and hearing-impaired patrons, six American Sign Language interpreted performances with highly trained interpreters are offered each season. Complimentary infrared listening devices and Telecoil hearing aid loops are available in all three of the Festival's theatres, and patrons may communicate with the Festival through the Oregon Telecommunications Relay Service. There is accessible seating in all performance venues, nearby accessible parking, and all of the above accommodations can be provided for the wide range of ancillary events that enrich the OSF experience, such as backstage tours, prefaces, prologues, and park talks. Each season a limited number of performances, post-show meet-and-greets, pre-show introductions, and backstage tours are open-captioned in Spanish.[46]

Archives

The archivists develop, preserve, and maintain a comprehensive collection of documents and oral histories, drawings and photographs, audio and video recordings, and artifacts pertaining to the artistic and administrative history and heritage of the Oregon Shakespeare Festival. Collecting, organizing, and preserving these materials of what otherwise is an ephemeral art form to archival standards is an ongoing effort aided in part by a two-year grant from the National Historical Publications and Research Commission, with material added on an ongoing basis.

The archives are open Monday through Friday, 9AM to 5PM, and the staff invites any inquiry or reference question by phone or email. Researchers and the general public are welcome to visit the archives by appointment. Other collections are available for research, although some collections have restrictions, and permission must be obtained for their use.[47][48][49]

The Archives include Education department records from 1947 on and document the department's programming and structural evolution. Print materials include annual reports, brochures, calendars, correspondence, course handouts, course readings, news clippings, newsletters, photographs, posters, scripts, statistics and survey reports, study guides, and teacher information kits, guides, and resource kits. Audio and video recordings include radio broadcasts and school visit program performances.

In May, 2013, the National Endowment for the Humanities awarded the Festival a $200,000 grant to digitize 2649 deteriorating tapes, films and videos and to make them publicly available through its website and the YouTube platform. The collection spans the history of the Festival from its inception in 1935 through 2012 and comprises an unparalleled and comprehensive record of Shakespearean and theatrical performance by a single U.S. theatre company. Included are full-length recordings of 541 of the 570 Festival productions from 1950 to 2012, including three or more varied interpretations of every play in the Shakespearean canon with exemplary casts before live audiences and the ballad opera series. The production recordings are supplemented by 44 adaptations broadcast on NBC radio, more than 100 hours of artist interviews, Shakespeare lectures by nationally and internationally renowned scholars and educators, production music, promotional recordings, and recordings of significant events in the company's history.[50] Also included are the home movies of founder Angus Bowmer, Southern Oregon Normal School events and rare footage of the initial 1935 Festival season!

Volunteers

The professional staff is augmented by volunteers—approximately 700 contributing about 32,000 hours each year. Tudor Guild volunteers staff the brass rubbing center, concession stands, and gift shop. Volunteers welcome visitors to the campus and answer their questions, staff the Green Show information table and welcome center, facilitate post-matinee discussions, provide concierge services for student groups, and supplement the professional ushers at all three theatres. Behind the scenes, volunteers help with office tasks such as preparing will-call tickets for pickup, sorting mail, filing, copying, mailings, and transcribing interviews. They work in the Archives, Costume Shop, Costume Warehouse, and Scene Shop, help with auditions, and serve as attendants in the company fitness facility. Among occasional tasks too numerous to provide a complete list, volunteers assist with access services and the periodic audience surveys, drive company vehicles, providing transportation for visiting dignitaries, and direct traffic during "strike" at the end of the season. Each year, company members present a thank you show titled Love's Labors for the volunteers.[51]

Stage Technology

The availability of small inexpensive computing platforms, LEDs, and compact powerful batteries allows special effects to be built into props, costumes, and scenery. Lighting, atmospherics, sounds, even motorized movement can be programmed into devices and controlled by the actors or remotely. WiFi and Bluetooth devices allow for wireless communication between the control console and the effect. For example, the LEDs built into a dress can be remotely illuminated and colors changed live while on stage. Costumes in Head Over Heels (a musical by Lolita Snipes), The Wiz, and The Winter's Tale are recent examples of wireless control. Lanterns, candles, fireflies, and other effects built into props and scenery also utilize embedded electronics.

The theatres feature Meyer speakers, Yamaha mixing consoles, Clear-Com Freespeak wireless communication, Sennheiser wireless microphone systems and Qlab software playback for their theater spaces. The Elizabethan Theater underwent a major audio system re-design with Meyer Sound Laboratories in 2014. The install included various types of Mina line arrays (UPQ-1Ps, UPQ-2Ps, MM4-Xps, 500 HPs, UPM-1Xps and UP-4Xps).[52]

Publications

All playgoers are offered a complimentary Playbill with a synopsis of the plays, cast lists, and directors' statements. All members receive 3 editions of Prologue each season (one each for spring, summer, and fall). This magazine contains selected articles on directors, actors, costumes, props, and plays each season. Another publication that is made available at higher donor levels is Illuminations, a comprehensive guide to each year's plays. Illuminations includes synopses, themes, information on playwrights and historical and other contextual information.[53] Each year, the Festival publishes Teachers First! providing information on the season's plays including age suitability, the seasonal calendar, ordering and discount information.

The annual Souvenir Program. includes photographic highlights of each play and special articles along with pictures and biographies of actors, playwrights, and the many people who work behind the scenes. A chart emphasizing the repertory nature of OSF lists all the actors and their parts in the plays.

The Festival also publishes a Bard's Scorecard, which lists all of William Shakespeare's Plays, the years OSF produced them, and allows repeat patrons to cross off which plays they've seen towards completing the canon.

Professional memberships

OSF is a constituent of Theatre Communications Group, the national service organization for the not-for-profit theatre world, and a member of the Shakespeare Theatre Association of America. It operates under contracts with Actors' Equity Association, The Union of Professional Actors and Stage Managers in the United States, and the Stage Directors and Choreographers Society, Inc., an independent national labor union.

Productions

2018 Season

The following plays are scheduled for the 2018 season.[54]

Plays being presented in the Allen Elizabethan Theater (15 June through 14 October):

- Love's Labour's Lost*

- Romeo and Juliet*

- The Book of Will

Plays being presented in the Angus Bowmer Theatre (16 February to 27 October):

- Destiny of Desire

- Oklahoma!

- Othello*

- Sense and Sensibility

- Snow in Midsummer

Plays being presented in the Thomas Theatre (21 February to 28 October):

- Henry V*

- Manahatta**

- The Way the Mountain Moved**

* denotes a play written by William Shakespeare

** denotes a world premiere play

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Leary, K. (2009). Images of America: Oregon Shakespeare Festival. Charleston: Arcadia Publishing.

- 1 2 "The People of OSF: Our Company Members". Oregon Shakespeare Festival. 2008. Retrieved 2008-05-30.

- ↑ Gregio, Marcus (2004). Shakespeare Festivals Around the World. Xlibris Corporation.

- ↑ "OSF Announces New Green Show". Ashland Daily Tidings. 2008-05-31. Retrieved 2008-06-21.

- ↑ Varbel Bill. (2008). "Many Colors in Newly Revamped Green Show". Ashland Daily Tidings. Retrieved 2008-06-21.

- ↑ Murphy, M. (2005). The Stage is Set for a Meteoric Success. A Tradition of Shakespeare 1935–2005. Ashland Daily Tidings.

- 1 2 "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-03-14. Retrieved 2012-01-07.

- ↑ Oregon Shakespeare Festival Archives. Used with the permission of Amy Richard, Media Relations, OSF: media@osfashland.org

- ↑ Darling, John (August 2, 2010). "This is OSF...on NBC". Ashland Daily Tidings.

- ↑ Zoglin, Richard (May 27, 2003). "Bigger than Broadway!". Time. Retrieved May 30, 2008.

- ↑ "OSF's Bill Rauch honored by Actors' Equity for diversity efforts". Ashland Daily Tidings. January 24, 2018. Retrieved January 30, 2018.

- ↑ "12 Stars Who Won Tony Awards for their Broadway Debut Performances". Tonyawards.com. May 20, 2015. Retrieved 2015-05-23.

- ↑ "OSF Sets New AMERICAN REVOLUTIONS Commissions". April 30, 2015. Retrieved 2015-05-23.

- ↑ Shapiro, Eben (December 6, 2017). "Top 10 Plays and Musicals of 2017". Retrieved 2018-01-22.

- ↑ Cooper, Michael (February 16, 2018), World Trade Center Arts Space Gets a Lease, and a Leader, retrieved 2018-04-22

- 1 2 3 "Play On!". Oregon Shakespeare Festival. Retrieved 2017-01-20.

- ↑ "Press Releases and Information". Oregon Shakespeare Festival. 2014. Retrieved 2014-03-27.

- ↑ Cwi, D. (1977). Economic Impacts of Arts and Cultural Institutions. National Endowment for the Arts.

- ↑ Varble, B. (2015). "OSF draws more than 390,000 Patrons in 2015 season". Ashland Daily Tidings. Retrieved 2016-03-04.

- ↑ Darling, J. (November 8, 2017). "That's A Wrap". Ashland Daily Tidings. Retrieved 2018-01-22.

- ↑ "4th of July Celebration". Ashland Chamber of Commerce. 2015. Retrieved 2015-05-23.

- ↑ Roberts, Dmae (2016). "Asian Americans take center stage at national theater festival, conference in Ashland". The Oregonian. Retrieved 2017-01-20.

- 1 2 Bowmer, Angus (1978). Shreds and Patches: The Ashland Elizabethan Stage. Ashland, Oregon: Oregon Shakespeare Association. OCLC 6040869.

- ↑ "The Paul G. Allen Family Foundation Awards OSF $3,000,000 Grant". Oregon Shakespeare Festival. Retrieved 2014-03-13.

- ↑ Oregon Shakespearean Festival Association. Shakespeare 1970. Ashland, Oregon: Oregon Shakespearean Festival Association, 1970.

- ↑ Oregon Shakespearean Festival Association. Stage II. Ashland, Oregon: Oregon Shakespearean Festival Association, 1970

- ↑ Galvin, R (July 17, 2011). "Bowmer Re-opening for August 2". Medford Mail Tribune. Retrieved August 25, 2011.

- ↑ Hathaway, Brad (August 2, 2011). "Temporary Nomads with Tent No More". Retrieved August 25, 2011.

- ↑ Hayden, D. "Bowmer in the Park: Anatomy of a Crisis". Ashland, Oregon: Sneak Preview 22, 9.

- ↑ Hugely, Marty (August 2, 2011). "Oregon Shakespeare Festival Re-opens Bowmer Theatre, and Tallies the Losses". Oregonlive.com. Retrieved August 25, 2011.

- ↑ Wheeler, Sam (July 8, 2011). "'Bowmer in the Park' Begins". Ashland Daily Tidings. Retrieved August 25, 2011.

- ↑ Wheeler, Sam (March 10, 2012). "OSF collects $2.6 million in insurance from Bowmer closure". Ashland Daily Tidings. Retrieved May 2, 2012.

- ↑ Conrad, Chris (17 March 2012). "'New' No More". Dailytidings.com. Retrieved 2012-11-10.

- ↑ Kent, Roberta (March 17, 2014). "OSF's Production Facility in Talent Is Complete". Ashland Daily Tidings. Retrieved March 26, 2014.

- ↑ Aldous, Vickie (2016-02-29). "Oregon Shakespeare Festival dedicates new rehearsal center". Ashland Daily Tidings. Retrieved 2017-01-21.

- ↑ "An Expansive New Space". Oregon Shakespeare Festival. Retrieved 2017-01-21.

- ↑ Kent, Roberta (March 17, 2014). "OSF's Production Facility in Talent Is Complete". Ashland Daily Tidings. Retrieved March 26, 2014.

- ↑ Oregon Shakespeare Festival (2015). Member Presale Ordering Guide (Report).

- ↑ Oregon Shakespeare Festival (2017). Souvenir Program (Report).

- ↑ "FAIR: Fellowships, Internships & More". Osfashland.org. 2016-07-01. Retrieved 2016-10-07.

- ↑ "About Us". Osfashland.org. Retrieved 2016-10-07.

- ↑ "Teacher Trainings". Osfashland.org. 2016-07-02. Retrieved 2016-10-07.

- ↑ Lacaze, Katherine (2016-09-30). "OSF goes into classrooms across the state - News - MailTribune.com - Medford, OR". MailTribune.com. Retrieved 2016-10-07.

- ↑ "Public Events and Classes". Retrieved 2017-01-21.

- ↑ "Oregon Shakespeare Festival : Archives Division : Education Department Records, 1947-2010". Osfashland.org. Retrieved 2016-10-07.

- ↑ "Accessibility Services" (PDF). Oregon Shakespeare Festival. 2011. Retrieved 2012-05-01.

- ↑ "Our History". Oregon Shakespeare Festival. Retrieved 2013-03-12.

- ↑ "Archives". Oregon Shakespeare Festival. Retrieved 2013-03-12.

- ↑ "Oregon Shakespeare Festival Archives". Oregon Shakespeare Festival. Retrieved 2013-03-12.

- ↑ "$200,000 NEH Grant Supports Digitization". Oregon Shakespeare Festival. Retrieved 2013-07-23.

- ↑ Coombs, Mary. "A huge cast of volunteers makes the show go on". Ashland Daily Tidings. Retrieved March 9, 2016.

- ↑ Stabler, David (2014-04-21). "Oregon Shakespeare Festival installs new, hopefully improved, sound system in outdoor theater". The Oregonian. Retrieved 2017-02-08.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2010-06-12. Retrieved 2010-04-25.

- ↑ "On Stage". Oregon Shakespeare Festival. Retrieved 2 February 2018.

External links

- Oregon Shakespeare Festival in The Oregon Encyclopedia

- Oregon Shakespeare Festival official website, including a production history

- The Oregon Shakespeare Festival Documentary produced by Oregon Public Broadcasting

- Oregon Shakespeare Festival at the Internet Broadway Database

Coordinates: 42°11′46″N 122°42′54″W / 42.1962°N 122.7151°W